Etiology

Pituitary masses may be classified based on their underlying etiology: for example, pituitary adenoma, pituitary hyperplasia, nonadenomatous tumors, and vascular, inflammatory, or infective lesions.

Pituitary adenomas

Prolactinoma

Accounts for over 50% of all pituitary adenomas and are the most common clinically relevant pituitary adenoma.[1][7][8]

Adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting (Cushing disease)

While exogenous steroids are the most common cause of Cushing syndrome in adults, Cushing disease is the most common cause of endogenous Cushing syndrome (70% to 80%).[9] Cushing disease accounts for 4% of all functional adenomas.[1] The global prevalence is 2.2 cases per 100,000 people, with an incidence rate of 0.24 per 100,000 person-years.[10]

Growth hormone (GH)-secreting

The most common cause of acromegaly and accounts for 12% of all functional adenomas.[1] The global prevalence of acromegaly is 5.9 cases per 100,000 people, with an incidence rate of 0.38 cases per 100,000 person-years.[11]

Nonfunctional or gonadotropin-secreting

Nonfunctional adenomas are the second most common cause of pituitary adenoma and account for up to 30% of all pituitary adenomas.[1] Most are gonadotroph cell adenomas.[12] All patients with clinically nonfunctional tumors should have an alpha-subunit glycoprotein determination. High-normal or elevated gonadotropins in these patients are suspicious for an underlying gonadotroph adenoma.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain computed tomography scan showing a small pituitary mass encroaching on the right cavernous sinusBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2193 [Citation ends].

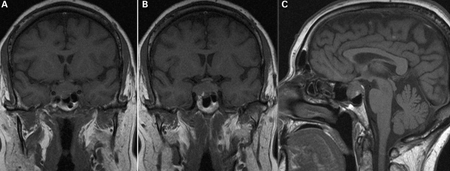

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: (A) Coronal T1 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a pituitary mass with expansion of the pituitary fossa. (B) Coronal T1 weighted MRI scan showing a pituitary mass extending into the cavernous sinus, particularly on the right. (C) Sagittal T1 weighted MRI scan of the pituitary tumorBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2193 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: (A) Coronal T1 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a pituitary mass with expansion of the pituitary fossa. (B) Coronal T1 weighted MRI scan showing a pituitary mass extending into the cavernous sinus, particularly on the right. (C) Sagittal T1 weighted MRI scan of the pituitary tumorBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2193 [Citation ends].

Thyrotropin (TSH) secreting

Accounts for <1% of all functional pituitary tumors.[1]

Pituitary hyperplasia

Lactotroph hyperplasia

Develops as a physiologic response to pregnancy.

Thyrotroph hyperplasia

Develops in response to longstanding primary hypothyroidism.[13]

Gonadotroph hyperplasia

Develops in response to longstanding hypogonadism.

Somatotroph hyperplasia

Develops in response to ectopic secretion of GH-releasing hormone; usually associated with neuroendocrine tumors (pancreas, kidneys, adrenals, or lungs).

Corticotroph hyperplasia

A result of longstanding adrenal deficiency (e.g., untreated congenital adrenal hyperplasia) or in patients having undergone adrenalectomy for Cushing disease.

Nonadenomatous benign tumors

Craniopharyngioma

Derived from squamous cell rests in the remnants of Rathke pouch. Account for 1% to 3% of all adult intracranial tumors.[14]

Meningioma

Slow-growing tumors can originate from any dural surface. About 10% of meningiomas arise in the parasellar region.[15] Purely intrasellar tumors are rare.

Malignant tumors

Germ cell tumors

Rare intracranial tumors; incidence ranges from 0.3% to 0.5% of all intracranial tumors in Western countries, and higher in Asian countries.[16]

Lymphoma and chordoma

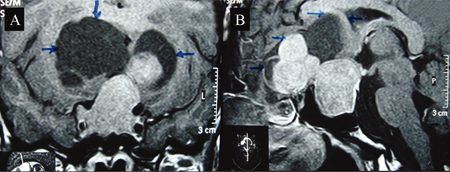

Sellar tumors that are extremely rare.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) post-contrast magnetic resonance image T1 weighted sections showing a large intrasellar tumor with suprasellar component. Suprasellar solid component shows a lobulated margin with peripheral non-enhancing cystic areas (margins shown by arrows), which are mildly hyperintense compared with cerebrospinal fluid in basal cisternsBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.01.2009.1483 [Citation ends].

Metastatic disease

Metastases to the pituitary gland and sella are uncommon and account for less than 1% of sellar masses.[17] The most common primary malignancies to metastasize to the pituitary gland are breast and lung cancers.[18]

Pituitary carcinoma

Inflammatory/infective/iatrogenic

Hypophysitis

Lymphocytic hypophysitis: autoimmune disease that usually presents in women during or shortly after pregnancy; infrequent in men.

Drug therapy-induced hypophysitis: a recognized adverse effect of immunotherapy, particularly associated with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies and PD-1 inhibitors (immune checkpoint inhibitors used in the treatment of malignancy).[23] This complication is two to five times more common in males than in females. Drug therapy-induced hypophysitis typically occurs in patients over the age of 60; its prevalence depends upon the medication used.[24][25][26]

Pituitary abscess

Rare and can develop following hematogenous spread of infection, extension from the sinuses, or meningeal sepsis.[27] Abscess development may arise in normal pituitary tissue or in a preexisting sellar lesion (e.g., adenoma, craniopharyngioma, or Rathke cleft cyst), with or without a recent history of surgical treatment.[27]

Vascular

Cerebral aneurysms with intrasellar extension

Accounts for about 1-2% of all intracranial aneurysms.[28] Usually originates from the cavernous or supraclinoid portions of the internal carotid artery.

Pituitary apoplexy

Rare syndrome resulting from pituitary hemorrhage or infarction. Most commonly occurs within a preexisting pituitary adenoma, but can occur in nonadenomatous lesions (e.g., a Rathke cleft cyst, sellar tuberculoma, hypophysitis, pituitary abscess, or craniopharyngioma).[29] Predisposing conditions include some drugs (e.g., anticoagulation therapy, dopamine agonist, gonadotropin agonist), cardiac surgery, head trauma, and dynamic testing of pituitary function.[30]

Can also occur in normal pituitary tissue, during the peri- or postpartum period, as a consequence of hypovolemic shock (Sheehan syndrome).[29]

Other causes

Other lesions that may present as or mimic a pituitary mass include:

Rathke cleft cyst: an anatomic anomaly arising from craniopharyngeal duct remnants. They are common lesions, reported incidentally in up to 33% of autopsy cases.[31] They are two to three times more common in females than in males. They can be seen at any age but, when symptomatic, usually present between age 40 and 60 years.

Empty sella syndrome: develops secondary to a communication between the pituitary fossa and the subarachnoid space. Cerebrospinal fluid herniates into the sella turcica, causing sella remodeling and enlargement, along with flattening of the pituitary gland. Predisposing conditions include congenital anatomic abnormalities, complications arising from a previous pituitary tumor (surgery, irradiation, or tumor infarction), and regression of the pituitary (e.g. following Sheehan syndrome or hypophysitis).[32]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer