Etiology

A detailed history, clinical exam, and investigations specific for the probable causes help in diagnosing the cause of liver test abnormality in most patients.[3] Etiology may be:

Infectious

Toxin-, medication-, or substance-related

Metabolic

Hereditary

Autoimmune

Benign biliary obstructive

Neoplastic

Cardiovascular

Pregnancy-related

Hepatic comorbidities.

Infectious

Viral hepatitis

The hepatotropic viruses (A, B, C, D, E) cause acute or chronic liver disease and can result in a predominantly hepatocellular pattern of liver test elevations.

Viral hepatitis A remains a significant cause of acute viral hepatitis in developing countries, mostly occurring in children. In the US, 2265 cases were reported in 2022, with estimates that the actual number of infections would have been closer to 4500.[10] Hepatitis A does not cause chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis B infection can cause acute and chronic infection, particularly in populations at increased risk of exposure (e.g., people who have traveled to a part of the world where the disease is endemic, have a high-risk sexual history, or use intravenous drugs). The liver test pattern varies depending on the immune response in the patient. In the US, 2126 cases were reported in 2022, with experts estimating the actual number to be around 13,800.[11]

Hepatitis C is the most common blood-borne infection and the leading cause of chronic viral infection of the liver in the developed world. Approximately 2.4 million US adults have chronic hepatitis C infection, with almost 13,000 deaths reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021.[12] Worldwide, there are approximately 71 million people chronically infected with hepatitis C virus.[13]

Hepatitis D is a defective virus that requires hepatitis B virus, in the form of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), for assembly of virions and infectivity. Thus, hepatitis D infection is limited to HBsAg carriers. Hepatitis D infection may occur at the same time as acute hepatitis B infection (coinfection) or may occur in people who have existing chronic hepatitis B infection (superinfection). Hepatitis D infection is most common in Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, West and Central Africa, East Asia, and the Amazon Basin in South America.[10]

Hepatitis E is prevalent in the developing world, with epidemics involving large numbers of people reported in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Central America, and increasingly recognized as a common cause of acute hepatitis infections among adults in industrialized countries, not just returning travelers.[10] It causes acute infection (rarely chronic), and symptoms are usually mild unless there is a coexistent underlying liver pathology. However, death in pregnant women has been reported.[14]

Other infections

Viral diseases resulting in liver dysfunction that usually cause only self-limiting acute infections in immunocompetent patients include:

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

HIV infection

Tuberculosis may be disseminated and may involve the liver.

Sepsis and shock may lead to acute liver failure.

Toxin- or substance-related

Alcohol

The prevalence of liver disease associated with alcohol varies geographically. Alcohol is one of the most common causes of cirrhosis in the Western world, with its associated morbidity and mortality. Chronic alcoholic liver disease and acute alcoholic hepatitis are associated with elevation of serum aminotransferases.[17][18]

Harmful alcohol use (≥3 drinks/day or ≥21/week in men and ≥2 drinks/day or ≥14/week in women) is a risk factor for liver damage and alcohol-associated liver disease; the quantity of alcohol ingested is the single most important risk factor.[18]

Drugs and toxins

Many medications may result in acute and chronic elevation of liver tests. Some effects are due to direct (dose-dependent, intrinsic, and predictable) hepatotoxicity; others may be idiosyncratic drug reactions (largely dose-independent and unpredictable).[19][20]

Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury is uncommon, occurring in only 1 in 1000 to 1 in 1,000,000 individuals exposed to an approved drug.[20][21][22]

Another mechanism of hepatotoxicity, indirect drug-induced liver injury, arises when the biological action of the drug affects the host immune system, leading to a secondary form of liver injury.[20]

Some of the more common drugs that are associated with abnormal liver tests include:

Acetaminophen

Antiretroviral therapy (ART)

Amiodarone

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., diclofenac)[23]

Chlorpromazine

Halothane

Estrogenic or anabolic corticosteroids (including oral contraceptives)

Statins[24]

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

Isoniazid

Ketoconazole

Methotrexate

Valproate sodium

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., pazopanib)[23]

Bile salt export pump inhibitors (e.g., bosentan, cyclosporine).[23]

Drugs and medications may be hepatotoxic when taken in accidental or deliberate overdose.[20] Other possible toxins include poisons, such as mushrooms (e.g., Amanita phalloides), herbal preparations (e.g., cascara, chaparral, comfrey, kava, ma huang), or industrial chemicals (e.g., carbon tetrachloride, trichloroethylene, paraquat).

Herbal or natural supplements have emerged as a major cause of elevated liver enzymes, hepatotoxicity, and acute liver failure.[20][25][26] In many cases, the exact herbal component associated with hepatotoxicity cannot be identified due to frequent combinations of herbal ingredients and the potential presence of other hepatotoxins.

Metabolic or hereditary

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)

A spectrum of disease, encompassing:[27][28]

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver: previously known as nonalcoholic fatty liver; characterized by isolated hepatic steatosis; and

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH): previously known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; where additional inflammation and cellular injury, with or without fibrosis, is present. MASH may lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

In MASLD, ≥5% of hepatocytes display macrovesicular steatosis in the absence of another obvious cause (e.g., medications, starvation, monogenic disorders) in individuals who drink little or no alcohol.[29] It is rapidly becoming the most frequent cause of liver disease with the increasing prevalence of obesity and its associated complications.[29] Additional risk factors for MASLD include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.[28][29] One meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of MASLD in the US to be 47.8%, with similar high prevalence in many other countries.[30] The estimated global prevalence of MASLD among adults is 32%.[30] The disease frequently presents as asymptomatic elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or alanine aminotransferase (ALT).

Although MASLD is observed predominantly in people with obesity and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus, an estimated 4% to 20% of people with MASLD have lean body habitus.[29][31][32][33][34][35][36]

Gilbert syndrome

This is not actually a disease, but is a conjugation defect without clinical consequence. It is the most common cause of mild bilirubin elevation. The other liver tests are normal and ≥90% of bilirubin is unconjugated, characterized by a disproportionate elevation of indirect bilirubin on fractionated assays.[37]

Hemochromatosis

This is a multisystem disorder in which dysregulated dietary iron absorption and increased iron release from macrophages lead to iron overload.

Although the genetic pattern (C282Y homozygous) associated with hemochromatosis is prevalent in 1 of 227 people of white ancestry, the clinical disease is less common because of variable penetrance. Other mutations are also associated with iron overload states although they are less likely to lead to organ damage.

Symptoms are nonspecific but may include lethargy, fatigue, loss of libido, arthropathy, and skin hyperpigmentation.

During the early stages, liver tests are normal. Significant liver damage may be present despite normal standard liver tests and frequently occurs in association with hepatic comorbidity such as alcohol-associated liver disease and MASLD.[38]

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

This is a disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance and codominant expression, with a genetic prevalence of approximately 1 in 3500 in the US.[39] It results from allele mutations (most commonly allele Z) in the SERPINA1 gene at the protease inhibitor (PI) locus.

Patients may present with lung symptoms and can have a normal or hepatocellular pattern of liver injury, with occasional cholestatic pattern. Liver fibrosis has been detected in 20% to 36% of asymptomatic adults with PI*ZZ alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, while the reported prevalence of cirrhosis ranges from 2% to 43%.[40][41][42]

Measurements of serum quantitative alpha-1 antitrypsin level and alpha-1 antitrypsin protease inhibitor phenotype are the most helpful blood tests.

Wilson disease

This is an autosomal recessive disease that is due to mutations in the ATP7B gene. It is a copper transport protein deficiency disease with a variable presentation.

It is caused by accumulation of copper in the liver and other tissues, including the brain.

A rare condition, usually diagnosed in children or young adults.

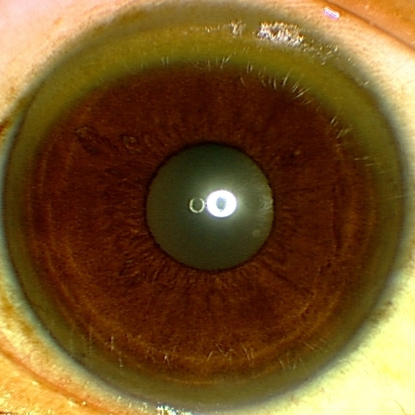

Patients may have neurologic symptoms (e.g., tremors) or eye changes (e.g., Kayser-Fleischer rings). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Eye demonstrating Kayser-Fleischer ringAdapted from BMJ (2009), used with permission; copyright 2009 by the BMJ Publishing Group [Citation ends].

One or more psychiatric condition may be present at a time. Patients often have abnormal behavior, personality change, depression, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and cognitive impairment.[43]

The liver presentation can vary from a longstanding mild hepatocellular pattern to a picture similar to the abnormalities seen with hemolysis or a cholestatic pattern of injury.

Characterized by low serum ceruloplasmin and elevated 24-hour urinary copper excretion; however, diagnosis may also require a combination of ophthalmologic assessment for Kayser-Fleischer rings, liver biopsy, and molecular genetic testing.

Immunologic/inflammatory

Autoimmune hepatitis

This condition is prevalent worldwide, affecting all ethnic groups and ages, with an approximate 4:1 female predominance.

The disease typically has a hepatocellular pattern of injury (AST and ALT elevations predominate). However, some patients have an overlap syndrome with primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis and have a mixed pattern.[4]

Primary biliary cholangitis

This is an uncommon condition, with a 9:1 female predominance.

Patients have a cholestatic pattern of disease. An increased elevation of aminotransferases could suggest overlap syndrome with autoimmune hepatitis.

Between 20% and 25% of patients are asymptomatic.

Symptoms, when present, can be nonspecific (e.g., fatigue, malaise, pruritus, or skin hyperpigmentation). Xanthelasma (cholesterol deposits in the skin around the eyes; manifestations of hypercholesterolemia) may be seen.

A positive antimitochondrial antibody is the hallmark of this disease, seen in high titer in >90% of cases.[44]

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

This is frequently associated with inflammatory bowel disease, which is present in 60% to 80% of cases, and most commonly involves ulcerative colitis.[45]

Occurs in 3% to 4% of patients with Crohn disease and 3% to 8% of patients with ulcerative colitis.

It causes a cholestatic or mixed pattern on liver tests.

Patients may be positive for perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody.

Bile duct stricturing can be seen on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.[46]

The risk of cholangiocarcinoma is increased.[47]

Benign biliary obstructive and neoplastic

Intra- and extrahepatic biliary obstruction (e.g., due to stones, cysts, primary and secondary liver malignancies, and pancreatic and biliary malignancies) cause predominant cholestatic/infiltrative patterns of liver disease. Symptoms vary depending on the underlying condition.

Cardiovascular

Portal vein thrombus, Budd-Chiari syndrome (hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction), systemic hypotension, heart failure, and shock may all lead to liver dysfunction. Systemic hypotension may have various etiologies. It may be associated with recent anesthesia and surgery, cardiac events, sepsis, or hemorrhage, and there may be known risk factors for venous thrombus. The history is frequently indicative of the etiology. Specific vascular studies may be used (e.g., Doppler venous studies).

Pregnancy-related

Liver conditions unique to pregnancy include the following.[48]

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: this condition usually occurs in late pregnancy (about 28 to 30 weeks' gestation) and is associated with itching, nausea, and vomiting. Alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels are elevated and aminotransferase levels may be increased. Total serum bile acid serum concentration is found to be high (usually over 10 micromol/L to 14 micromol/L).[49]

Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome: this is associated with preeclampsia, occurring in up to 10% of severe preeclampsia cases, and develops in late pregnancy (28 to 40 weeks' gestation) or postpartum. Biochemical studies are characterized by elevated AST and ALT, with mild elevation of direct bilirubin. The disease is associated with low platelets, abnormal red blood cell morphology, and a coagulation defect suggestive of disseminated intravascular coagulation. The condition can result in acute liver failure and is associated with increased fetal and maternal mortality.[50]

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: this is a rare disease affecting 1 in 7000 to 1 in 16,000 pregnancies. It occurs in late pregnancy (28 to 40 weeks' gestation), with rapid progression, and typically presents with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain followed by jaundice. Liver biopsy shows microvesicular steatosis. The disease can result in acute liver failure and is associated with increased maternal and fetal mortality.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer