Approach

Although history and physical examination frequently direct the clinician toward a working diagnosis, ancillary studies are often necessary. Most systemic disorders may be diagnosed with laboratory tests assessing neuroendocrine and ovarian function, and the majority of structural abnormalities are identified through pelvic examination and imaging studies.[12]

History

For women of reproductive age the date of their last spontaneous menstrual period, contraception used, and current pregnancy status should be determined.

Ask the patient about potential symptoms of hypoestrogenism including hot flushes, sleep disturbance, irritability, reduced libido, and vaginal dryness.

Cycle irregularity may be associated with conditions resulting in amenorrhea (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome).

Dysmenorrhea or painful cramps may be due to endometriosis, or to an obstructed outflow tract resulting in hematocolpos.[15]

A remote history of a traumatic head injury (can result in hypogonadism) or central nervous system infection (e.g., encephalitis) may be elicited.

Headache or visual field changes are suggestive of a central nervous system tumor.

Galactorrhea suggests hyperprolactinemia, which is commonly associated with secondary amenorrhea.

Poor nutritional status due to systemic illness, an eating disorder, and/or low body fat may result in hypothalamic dysfunction. An inquiry into a patient's health status, eating habits, and body image is necessary. Emotional stress can also impair hypothalamic function, resulting in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Extreme athleticism, especially with low body mass index (BMI), may result in a similar phenomenon.[16] Rare variants in genes associated with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism are found in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea, suggesting they may contribute to susceptibility.[17]

Chronic systemic illness (e.g., celiac disease[18]) may present with fatigue, malaise, anorexia, or weight loss.

Postpartum endometritis, dilatation and curettage, or other intrauterine infection can result in Asherman syndrome (obliterative endometrial process resulting in amenorrhea).

A complete medication history is important. Birth control pills, long-acting progestins, androgens, antipsychotic medications, and chronic opioid use can induce amenorrhea.[19] The type of medication may help identify a treated disorder that is the cause of amenorrhea.

A history of obstetric or surgical procedures should prompt consideration of intrauterine adhesions.

A history of chemotherapy or pelvic radiation therapy may suggest premature ovarian failure.

A family history of cessation of menses before age 40 years may indicate premature ovarian failure.

Physical examination

The patient's weight and height should be measured. Low BMI (10% less than ideal body weight) may suggest an eating disorder or the athletic triad (amenorrhea, osteoporosis, eating disorders).[16] Depending on culture and ancestry, 30% to 80% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome are overweight or obese, with central obesity (waist-to-hip ratio >0.85 or waist circumference >88 cm).[20]

On initial examination, careful attention should be given to male-pattern baldness, deepening of the voice, wide distribution of terminal hair (male pattern), increase in muscle bulk, breast atrophy, and clitoromegaly, suggesting hyperandrogenemia. These patterns may vary based on ancestry. If symptoms are slowly progressive, polycystic ovary syndrome or nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia is possible. If acute and progressive, the patient may be harboring an androgen-producing tumor (ovarian or adrenal).

External and internal genitalia are usually normal. Clitoromegaly suggests hyperandrogenemia or adrenal insufficiency. A pelvic examination may show vaginal atrophy, which is common with long-standing estrogen deficiency. The ovaries are usually non-palpable, however, they may be palpable in some patients with polycystic ovary syndrome or autoimmune oophoritis. The uterine cervix should be noted on examination. Internal examinations are not always possible, and the clinician may need to proceed with imaging options or an examination under anesthesia.

Skin examination may show acanthosis nigricans, acne, and hirsutism (polycystic ovary syndrome) or purple striae (Cushing syndrome).

Other signs of Cushing syndrome include central obesity, buffalo hump, easy bruising, proximal muscle weakness, and hypertension.

Check for signs of thyroid dysfunction including goitre, exophthalmos, lid lag, abnormal heart rate, or skin changes.

Check for signs of adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) including orthostatic hypotension, pigment changes, and decreased axillary or pubic hair.

Assess visual fields if a pituitary tumor is suspected.

Generalized Tanner staging exam is required to evaluate for estrogen effect. Even though this is most likely to be an issue for primary amenorrhea, patients with gonadal dysgenesis may have findings that suggest a hypoestrogenic state.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Androgen-secreting tumor in cut section of right ovaryBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.11.2008.1286 [Citation ends].

Laboratory tests

Urine or serum pregnancy: this is the first test performed in anyone of reproductive age presenting with secondary amenorrhea.[1]

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH): in concert with estradiol levels, gonadotropins help determine if amenorrhea is due to gonadal failure, hypothalamic dysfunction, or systemic or functional causes. FSH is more useful as a single test than luteinizing hormone (LH), and LH is not usually included in the initial investigations ordered. After ruling out pregnancy, this is the next test ordered.

Serum estradiol: low levels are suggestive of either primary ovarian failure (along with elevated FSH) or suppressed hypothalamic function (low FSH).

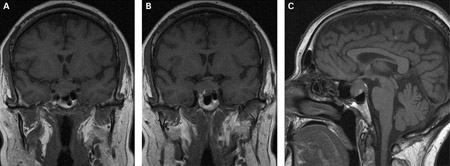

Serum prolactin: elevated levels of circulating prolactin (hyperprolactinemia), whether idiopathic or due to a pituitary adenoma, result in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. For persistently elevated levels, neuroimaging is indicated to rule out intracranial neoplasm.[21]

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): is indicated to rule out (primary) hypothyroidism. Mild or subclinical hypothyroidism likely will not result in menstrual irregularities.[12] It is proposed that elevated thyrotropin-releasing hormone stimulates prolactin secretion from the pituitary, suppressing FSH production.[22] Suppressed TSH suggests hyperthyroidism, which may cause oligomenorrhea.

Serum androgens are measured for signs of hyperandrogenism. Levels of androgens such as dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and free testosterone will be elevated in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome,[23] but might be significantly higher in patients with androgen-producing tumors.

A karyotype helps to confirm the etiology of premature ovarian failure in patients <30 years.[24]

Physiologic tests and imaging

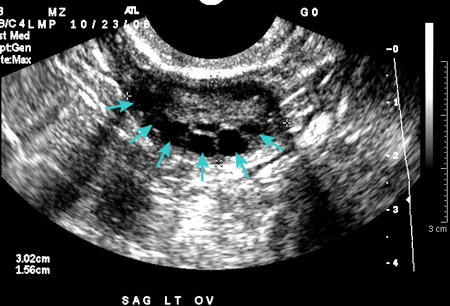

Transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound is performed if a pelvic examination is not possible. Ultrasound confirms normal anatomy, aids in the diagnosis of most structural abnormalities, and may obviate the need for progestin challenge. Transvaginal is the preferred modality, if possible, to evaluate endometrial thickness.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polycystic ovarian ultrasoundFrom the collection of Dr M. O. Goodarzi; used with permission [Citation ends].

Progestin challenge has been traditionally used to evaluate a functional outflow tract that has been adequately primed by normal levels of circulating estrogen. Although this assesses both the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and reproductive structures, there is debate as to whether it should be performed prior to noninvasive imaging or hormonal assays that may obviate the need for progesterone withdrawal. In patients with low levels of estradiol, a thin endometrial echo (atrophy) would be characteristic on transvaginal ultrasound. Lack of a withdrawal bleed may occur not only in patients with premature ovarian failure or hypothalamic dysfunction but also in patients with Asherman syndrome or polycystic ovary syndrome (e.g., elevated androgen levels may induce endometrial atrophy), all of which require substantially different evaluations. Should the lack of a withdrawal bleed be observed, a simple means to differentiate between structural and endocrinologic causes is to prime the uterus with estrogen for 4 to 8 weeks, followed by a second withdrawal challenge. (There are no clear recommendations as to length of exposure to low circulating levels of estradiol; the length of time given here is a suggestion.)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most effective tool for characterizing specific structural abnormalities and may prevent the need for surgical diagnosis.

If prolactin levels are significantly elevated, cranial MRI is indicated to rule out pituitary adenoma.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: (A) Coronal T1-weighted MRI scan showing a pituitary mass with expansion of the pituitary fossa (B) Coronal T1-weighted MRI scan showing a pituitary mass extending into the cavernous sinus, particularly on the right (C) Sagittal T1-weighted MRI scan of the pituitary tumorBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2193 [Citation ends].

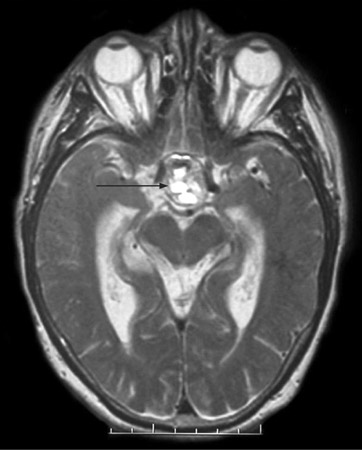

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: T2-weighted axial MRI scan showing a lesion in the pituitary fossa (arrow), displaying heterogeneous signal intensity suggesting recent apoplexyBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.09.2008.0902 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: T2-weighted axial MRI scan showing a lesion in the pituitary fossa (arrow), displaying heterogeneous signal intensity suggesting recent apoplexyBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.09.2008.0902 [Citation ends].

Bone density measurement may be indicated in selected patients, such as those with chronic hypoestrogenemia. This test may be less useful in younger patients who have not reached peak bone mass density (BMD). Use of steroidal contraceptives may also affect BMD.[25]

Asherman syndrome can be diagnosed by transvaginal ultrasound (may lack typical trilaminar appearance of endometrial echo found during normal proliferative phase); however, sonohysterography or hysterosalpingography are typical first tests used to assess the patient. Hysteroscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lower uterine segment in patient with Asherman syndrome, seen on hysterosalpingogramFrom the collection of Dr Meir Jonathon Solnik [Citation ends].

Other: leptin

Leptin is a cytokine secreted by adipocytes, the hypothalamus, and the pituitary gland that seems to have a significant impact on neuroendocrine and reproductive function as well as energy modulation. Serum leptin levels are affected by percentage of body fat, so women with eating disorders or poor nutritional status tend to have lower levels, representative of an alteration of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Therefore, replacement of leptin restores ovulatory menstruation in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea.[26][27]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer