Approach

Hypertension is usually asymptomatic, but patients may present with headaches, nosebleeds, visual symptoms, or neurologic symptoms. The main aims of history-taking are to identify symptoms suggestive of a secondary cause, to establish concomitant risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and to seek any symptoms suggestive of hypertension-mediated organ damage.[3][7][8]

Often there are no physical signs. However, a full exam for any signs of an underlying condition or hypertension-mediated organ damage is recommended. This should include height, weight, waist circumference, palpation and auscultation of the heart and carotid arteries, palpation of peripheral pulses, neurologic examination, and fundoscopy. An absence of symptoms or end organ damage with a history of normal blood pressure readings outside the clinical environment may occur with pseudohypertension.

Baseline screening tests are useful in all patients to look for complications of hypertension. Specific tests are only recommended if the clinical suspicion of an underlying secondary cause is high, as the majority of patients will have essential (primary) hypertension.

Blood pressure measurement

There are various types of blood pressure measurement techniques, each with their own benefits and limitations.[46]

Clinic-based blood pressure measurement

Before a diagnosis of hypertension can be confirmed, it is essential that the blood pressure is checked correctly, using a clinically validated and accurate device.[3][7][8] The patient should sit quietly for at least 5 minutes with the arm exposed and supported at the level of the heart, and the back resting against a chair. Ideally they should not have consumed caffeine or smoked tobacco within 30 minutes before testing. Canadian guidelines recommend electronic (oscillometric) upper arm devices instead of using auscultation to measure blood pressure in the office setting.[47]

If an automatic machine is used, it needs to be correctly calibrated, and calibration should be checked at least every 6 months.

The correct cuff size should be used; the US guidance recommends that the bladder encircles 80% of the arm, while the European guidance recommends that the bladder length should be 75% to 100% and the width 35% to 50% of the arm circumference.[2][7] It should be noted if a larger- or smaller-than-normal cuff size is used.[2] The cuff should be positioned at the level of the heart. The patient’s back and arm should be supported because muscle contractions can elevate blood pressure readings.

When using auscultation, the bell of the stethoscope should be used. The cuff should be inflated to at least 20 mmHg above the pressure at which the radial pulse disappears, and should be deflated at a rate of approximately 3 mmHg/second in order to accurately identify the point at which Korotkoff sounds can first be heard. Diastolic blood pressure in adults is measured as the point at which Korotkoff sounds disappear (Phase V).

Blood pressure should be checked in both arms, and the arm with the higher reading should be used. A consistent difference of >15 mmHg in systolic blood pressure between arms is associated with peripheral vascular disease and increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.[48] The US guidelines recommend at least two blood pressure readings taken 1-2 minutes apart.[2] European guidance recommends three readings, with additional measurements taken if the readings differ by >10 mmHg.[7] The blood pressure recorded should be the average of at least two readings.[2][7]

The patient’s pulse should be palpated to exclude arrhythmia. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends that patients with atrial fibrillation should have multiple manual auscultatory blood pressure measurements (as few automated devices have been calibrated for use in this population). The ESC also recommends measuring blood pressure 1 minute and 3 minutes after standing from a seated/lying position to exclude orthostatic hypotension, (defined as a blood pressure drop of ≥20/10 mmHg 1 and/or 3 minutes after standing following a 5 minute seated or lying position).[7]

Automated office blood pressure (AOBP) is intended to more accurately measure blood pressure.[49][50] Multiple measurements are taken while the patient is alone in a quiet room, sitting with legs uncrossed, back supported, and arm supported at heart level. Depending on the device used, 3 to 6 measurements are taken over a short time period and the mean blood pressure is calculated.[51] When using AOBP, hypertension is defined as ≥135/85 mmHg.

Out-of-office blood pressure measurement

Before therapy is initiated, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or regular home monitoring is recommended to document true hypertension outside the office setting.[7][52][53][54][55] One meta-analysis comparing clinic-based with home-based ABPM found that neither clinic- nor home-based measurements had sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be used as a single diagnostic test, and that doing so may lead to substantial over-diagnosis.[56]

ABPM has many advantages in that it helps to diagnose "white-coat hypertension" and masked hypertension, recognizes episodes of symptomatic hypotension, and identifies dipping patterns and early morning surges in blood pressure. Masked hypertension is defined as a normal blood pressure in the clinic or office (<130/90 mmHg), but an elevated blood pressure out of the clinic (ambulatory daytime blood pressure or home blood pressure >135/85 mmHg). There is no universal agreement on definitions of hypertension measured by out-of-office blood pressure monitoring, but European guidelines suggest a cutoff of 135/85 mmHg for daytime ABPM or home blood pressure.[7] The US American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines report estimates for corresponding home, daytime, night-time, and 24-hour ambulatory levels of BP e.g., an office blood pressure measurement of 130/80 mmHg corresponds to a home blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg, a daytime ABPM of 130/80 mmHg, a night-time ABPM of 110/65 mmHg, and a 24-hour ABPM of 125/75 mmHg.[2]

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends ABPM as the preferred method of out-of-office blood pressure measurement, followed by home blood pressure monitoring.[57]

Home blood pressure readings should be recorded using a validated monitor when the patient is seated, with their back and arm supported, after 5 minutes’ rest. Two readings should be recorded, 1-2 minutes apart, in the morning (before taking medication) and again in the evening. Measurements should be taken for at least 3 days, ideally 7. The home blood pressure reading is the average of all of the measurements.[7]

Screening for hypertension

As most people with hypertension are asymptomatic, regular blood pressure measurements are recommended to detect the condition. The ACC/AHA recommend yearly measurements following an initial blood pressure evaluation. Adults with an elevated blood pressure should have a repeat evaluation in 3-6 months.[2]

The European Society of Cardiology recommends that opportunistic screening for elevated blood pressure and hypertension should be considered at least every 3 years for adults <40 years, and at least once a year for adults ≥40 years.[7] For those with elevated blood pressure who do not meet the criteria for treatment, the European Society of Cardiology recommends a repeat risk assessment and blood pressure measurement within 1 year.[7]

Concomitant cardiovascular risk factors

Establishing concomitant cardiovascular risk factors is essential to define overall cardiovascular risk.

Smoking: enquiries should include type of cigarette or tobacco, quantity, and duration of habit. Patients have a tendency to under-report, and nonsmokers may be exposed to passive cigarette smoking in the home if a partner is a heavy smoker.

Diabetes mellitus: this is a strong risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The target blood pressure for a diabetic hypertensive patient is 130/80 mmHg.

Known ischemic heart disease or previous myocardial infarction.

Previous stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Elevation of cholesterol or triglycerides: patients may be unaware of such elevation if they have never been tested.

Family history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, or renal disease.

Identification of a secondary cause

Although in the majority of patients hypertension is primary/essential, there are certain features that may lead to a suspicion of an underlying cause (secondary hypertension):

Young patient (<40 years)

Rapid onset of hypertension

Sudden change in blood pressure readings when previously well controlled on a particular therapy

Resistant hypertension that is unresponsive to pharmacologic therapies.

If a secondary cause is suspected, then the presence of specific symptoms may suggest a particular cause and guide further investigations:

Flash pulmonary edema or widespread atherosclerosis may indicate renal artery stenosis

Cold legs may indicate poor distal perfusion secondary to aortic coarctation

Swelling and hypertension in a pregnant patient should raise suspicion of preeclampsia

Edema and reports of foamy urine in a nonpregnant patient may represent nephrotic syndrome

A history of renal impairment, prostatic enlargement, previous urethral instrumentation, or renal calculi is consistent with obstructive uropathy or chronic kidney disease

A family history of polycystic kidney disease, intracranial aneurysms, or subarachnoid hemorrhage in a young patient (age 20-34 years) with hypertension is strongly suggestive of polycystic kidney disease

Endocrine causes may present with numerous nonspecific symptoms, but pheochromocytoma usually has episodic symptoms consistent with a hyperadrenergic state, such as panic attacks, sweating, palpitations, and abdominal cramps

Symptoms of low potassium, such as headaches, nocturia, and paresthesiae, may indicate hyperaldosteronism, although the majority of patients with this condition are normokalemic

Typical symptoms of Cushing syndrome are depression, weight gain, hirsutism, easy bruising, and low libido

Heat intolerance, sweating, palpitations, and weight loss may indicate an excess of thyroxine, while lethargy, constipation, weight gain, and depression are common findings with low circulating thyroxine levels

Symptoms of bone pain, paresthesiae, and myalgia may suggest hyperparathyroidism

Excessive daytime sleepiness in an obese patient, who may also complain of erectile dysfunction and restless sleep, may be a symptom of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome, or obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Partners are likely to give a history of loud snoring

Toxic causes include use of oral contraceptives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or chronic alcohol excess.

Physical findings suggestive of a secondary cause include the following:

Renal bruits may be audible with renal artery stenosis

Enlarged kidneys may be palpated in polycystic kidney disease. There may be accompanying hepatomegaly or a hernia

Arteriovenous fistulae may be present in a patient with end-stage kidney disease

Flank tenderness or prostatic enlargement on rectal exam may suggest a cause of obstructive uropathy

Facial edema or limb edema in a pregnant patient warrants urinary collection for proteinuria as suggestive of preeclampsia

Edema in a nonpregnant patient might be due to nephrotic syndrome

Radiofemoral delay and a disparity in blood pressure readings between the arms may be demonstrated with coarctation of the aorta, along with systolic or continuous cardiac murmurs. Distal pulses may be weak or impalpable

Cushing syndrome has well defined features, typically described as a moon face, thin arms and legs, truncal obesity, striae, and skin thinning

Isolated eyelid edema with dry skin and a thick tongue may suggest hypothyroidism, while exophthalmos, proptosis, and lid lag suggest hyperthyroidism due to Graves disease

The deposition of calcium just inside the iris, or palpation of jaw tumors, raises the possibility of hyperparathyroidism

Obesity predisposes to obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Obesity, maxillomandibular abnormalities, and macroglossia predispose to obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome

Chronic alcohol excess can result in a myriad of signs, such as jaundice, hepatomegaly, spider nevi, ascites, and general neglect of appearance.

Hypertension-mediated organ damage

Cardiovascular disease

Symptoms of cardiac failure include shortness of breath, ankle edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea. Angina may also be reported. Exam may reveal cardiac murmurs, thrills, or heaves.

Left ventricular hypertrophy diagnosed either by echocardiography or by electrocardiogram is well documented. It has prognostic utility in patients with hypertension.[58]

Cerebrovascular disease

Any history of symptoms suggestive of transient ischemic attack or stroke should be obtained. These may include speech difficulties, visual disturbance, or transient focal neurology.

Carotid bruits may indicate carotid artery stenosis and warrant further duplex imaging to determine blood flow and degree of stenosis.

There may be residual functional loss after a stroke.

Renal failure

May be asymptomatic, but urinary symptoms such as decreased or increased frequency of urination, pruritus, lethargy, and weight loss may suggest renal damage.

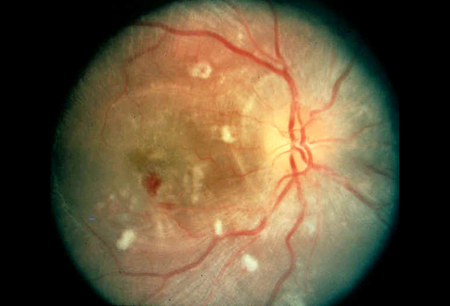

Retinopathy

This is often asymptomatic, but may present with visual loss or headaches.

Hypertensive retinopathy on fundoscopy is characterized by:

Arteriolar narrowing (graded 1-4, depending on the degree of narrowing)

Arteriolar venous nipping (constriction of veins at crossing points)

"Cotton wool spots" on the retina (due to ischemic changes)

Flame hemorrhages or papilledema.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypertensive retinopathyFrom the collection of Sunil Nadar, MBBS, FRCP, FESC, FACC and Gregory Lip, MD, FRCP, FESC, FACC [Citation ends].

Initial investigations

Baseline screening tests are useful in all patients to look for complications of hypertension.

An ECG can be easily performed and is useful to seek signs of previous myocardial infarction or left ventricular hypertrophy (a key prognostic factor). Echocardiography may be reserved for patients with clinical suspicion of cardiac failure or left ventricular hypertrophy.

A chest x-ray is helpful to look for evidence of cardiomegaly, widening of the left subclavian border, and a double bulge at the site of the aortic knuckle. This may be seen in coarctation of the aorta, along with notching of the ribs due to large collateral circulation.

Initial blood tests should include BUN, electrolytes, and creatinine, with random blood sugar and serum cholesterol (as part of overall cardiovascular risk assessment). If diabetes is suspected, a fasting blood sugar test is required. Potassium levels may be low in hyperaldosteronism, but are usually normal.

A urine dip test is performed to look for glycosuria and proteinuria, and the presence of casts may help determine an underlying renal cause, such as glomerulonephritis or nephrotic syndrome.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

How to record an ECG. Demonstrates placement of chest and limb electrodes.

Subsequent investigations

Specific tests are only recommended if the clinical suspicion of an underlying secondary cause is high, as the majority of patients will have essential hypertension. These include:

Blood tests

Plasma renin and aldosterone levels if hyperaldosteronism is suspected. Adrenal vein sampling to compare the ratio of renin to aldosterone in each kidney. A ratio >2 suggests an aldosterone-secreting tumor.[60][61]

Plasma renin activity is elevated in most patients with renal artery stenosis and is a good screening test.[62] A renal angiogram is the most specific and sensitive test.[63]

Late-night salivary cortisol will be elevated in Cushing disease, and this can be confirmed with the overnight dexamethasone suppression test.[64]

Liver function tests may be a useful screening tool if chronic alcohol excess and liver dysfunction are suspected.

Thyroid function tests, if clinical history leads to suspicion of hyper- or hypothyroidism.[7]

Serum calcium levels can be measured if hyperparathyroidism is a possibility.

Urine tests

24-hour urine collection to measure: catecholamines to exclude a pheochromocytoma; protein levels in suspected preeclampsia or nephrotic syndrome. However, in the case of preeclampsia and nephritic syndrome, a spot urine creatinine ratio can offer comparable results.

Imaging

Ultrasound of kidneys and adrenal glands: a unilateral small kidney would be suspicious of chronic pyelonephritis or renal artery stenosis (causing renal atresia). Bilateral shrunken kidneys are consistent with chronic renal failure. Hydronephrosis may confirm an obstructive cause. This could be followed by a computed tomography (CT) pyelogram if renal calculi are strongly suspected. Polycystic kidneys are easily visualized on abdominal ultrasound.

CT of adrenals: this can be used to localize a pheochromocytoma if urinary catecholamines are suggestive of the diagnosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): can be used to investigate renal artery stenosis if a renal angiogram is contraindicated. It can identify and characterize an aortic coarctation, and be used to plan further treatment.[65] MRI is also useful for imaging the adrenals to localize a tumor in hyperaldosteronism or pheochromocytoma.

Biopsy

Renal biopsy: this is a definitive test to elicit the underlying cause of nephrotic syndrome.

Special tests for suspected obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS)

For the screening of obstructive sleep apnea, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence suggests considering the STOP-Bang Model.[36] This consists of a questionnaire asking about loud snoring, witnessed apneas, excessive daytime sleepiness, and hypertension combined with body mass index, age, neck circumference thresholds, plus sex.

The patient's level of daytime fatigue can be assessed using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.[36][66][67] [ Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) Opens in new window ] However, the American Heart Association recommend against its use as a screening tool, due to its low sensitivity (42%).[38]

Polysomnography is currently the definitive test. It includes electroencephalogram, electro-oculographic recording, air flow assessment, electromyogram, capnography, esophageal manometry, ECG, and pulse oximetry.[36]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer