Approach

The evaluation of the acutely psychotic patient includes a thorough history and physical exam, as well as relevant investigations. Based on the initial findings, further diagnostic tests may be warranted. Secondary causes must be considered and excluded before the psychosis is attributed to a primary psychotic disorder. The most common secondary cause of psychosis is drug toxicity from recreational, prescription, or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. Patients with organic causes, such as structural brain abnormalities or metabolic syndromes, usually have other physical manifestations that are readily detectable by history, neurologic exam, or routine laboratory tests. Brain imaging is reserved for patients with specific indications, such as head trauma or focal neurologic signs. The routine use of such imaging is unlikely to reveal an underlying organic cause but accepted practice varies depending on location.[57]

Medical history

A careful history should be taken to identify possible organic causes of the psychosis. The patient’s age, background, employment, stressors, medical history, and a history of onset and course of psychotic symptoms are essential for a differential diagnosis.[58] A careful history should be obtained even if the patient has a known primary psychotic disorder, as organic and psychiatric (i.e., nonorganic) causes can coexist. Specific features of the history include:

History of recent or past head trauma: a recent head trauma should raise suspicion of a subdural hematoma. Previous head trauma may cause a seizure disorder and increases the risk of schizophrenia.

Recent seizures or a known history of a seizure disorder: it is important to establish the timing of psychosis in relation to seizure activity (postictal, ictal, and interictal). A history of epilepsy is a risk factor for psychosis.

Neurologic symptoms: key symptoms that should prompt suspicion of organic central nervous system (CNS) disease include new-onset headaches or changes in headache pattern, focal weakness or sensory loss, visual disturbance (double vision or partial vision loss), and speech deficits, including dysarthrias and aphasias. Abnormal body movements, memory loss, and tremor in older patients should prompt suspicion of neurodegenerative disorders. Fluctuating consciousness may indicate delirium.

Recreational drug use: any recent use of recreational drugs such as alcohol, cocaine, cannabis, amphetamines, or phencyclidine should prompt suspicion of drug-induced psychosis. A history of heavy alcohol, benzodiazepine, or barbiturate use followed by abrupt cessation should raise suspicion of a withdrawal syndrome, especially if the onset is abrupt. The ASSIST-Lite is a brief screening tool developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) that has been devised to help detect and manage substance use and related problems in healthcare settings.[59]

Prescription medications: common offending medications include anticholinergic drugs, dopamine agonists, corticosteroids, adrenergic drugs (e.g., stimulants, propranolol, clonidine), and thyroid hormones. It is important to establish when any new drugs were started, or when doses were changed, and how the timing relates to the onset of symptoms.

OTC medications: commonly include antihistamines, dextromethorphan, and medications containing phenylpropanolamine, especially if used chronically or at very high doses.

Exposure to heavy metals: if the main water supply is from a well or the patient has any occupation or hobby that involves chemical or heavy metal exposure, heavy metal poisoning should be suspected. Physical symptoms of lead toxicity include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anemia, weakness in limbs, and convulsions. Common symptoms of arsenic poisoning are vomiting, diarrhea, kidney failure, pigmentation of soles and palms, hypersalivation, and progressive blindness. Mercury toxicity presents with symptoms of metallic taste, hypersalivation, gingivitis, tremors, and blushing. Psychosis with mercury toxicity is rare.

Exposure to organophosphates: a history of the use of pesticides (especially in farm workers) should prompt suspicion of organophosphate poisoning. The diagnosis is clinical. There is often an initial acute cholinergic crisis and an intermediate phase of respiratory paralysis (24 to 96 hours), followed at 1 to 3 weeks by neuropathy. Physical symptoms and signs include bronchospasm, nausea and vomiting, blurred vision, diaphoresis, confusion, anxiety, respiratory paralysis, and extrapyramidal symptoms.

Dietary history: vegan diet, eating disorders, malnutrition related to alcoholism, drug dependence, or deprivation increases risk of vitamin deficiencies. Deficiencies of vitamin B12, folate, thiamine, and niacin can all cause psychosis. A malabsorption syndrome may produce changes in bowel habit.

Recent surgery: hypoxia should be considered if an acute psychosis occurs during the postoperative period.

Family history may reveal a genetic-based neurologic, metabolic, or autoimmune disorder in a first-degree relative. Wilson disease is the most common inherited cause of psychosis. A history of a primary psychotic disorder in a first-degree relative may also be present.

Travel history: if infectious encephalitis is suspected as the cause, a travel history is important to assess the risk of exposure to infectious causes, such as parasites (rare in the US).

Psychotic-like experiences that are spiritual in nature may not be pathological if: they are not associated with suffering or social or functional impairment; they are compatible with patients’ cultural backgrounds and this is recognized by others of the same culture; there is an absence of psychiatric comorbidities.[60]

Physical exam

Initial assessment should consist of a complete physical and mental state exam. Important features in the general exam that may help to identify specific causes of psychosis include:

Fluctuations in the level of consciousness, suggesting delirium.

The presence of tachycardia and hypertension, suggesting thyrotoxicosis, drug intoxication, or an acute drug withdrawal syndrome.

The presence of a fever, prompting suspicion of encephalitis. Characteristic rashes may be noted on general inspection for some causes of encephalitis (e.g., syphilis).

Evidence of malnutrition, suggestive of vitamin deficiencies.

Signs of hypo- or hyperthyroidism or cushingoid features, prompting suspicion of an endocrine cause.

Noticeable joint deformities, rashes, or other specific signs associated with an underlying autoimmune disorder.

Dysmorphic body features, prompting consideration of the rare genetic and chromosomal causes.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary syphilis presenting pigmented macules and papules on the skin.CDC/Susan Lindsley; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A primary syphilitic chancre of the lip.CDC; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A primary syphilitic chancre of the lip.CDC; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Patient with Cushing syndrome before and after therapy.From the collection of Ty Carroll and James W. Findling, Endocrinology Center, Medical College of Wisconsin; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Patient with Cushing syndrome before and after therapy.From the collection of Ty Carroll and James W. Findling, Endocrinology Center, Medical College of Wisconsin; used with permission [Citation ends].

A thorough neurologic exam should be undertaken. Important features in the neurological exam that may suggest a neurologic cause include:

Aphasia

Ataxia

Babinski sign

Brisk tendon reflexes

Cranial nerve deficits

Facial mask

Gait disturbance

Hemianopia

Hemiparesis

Myoclonus

Neuropathy with weakness and decreased vibrational and position sense: may be seen in vitamin B deficiencies

Paresthesias

Signs of raised intracranial pressure: may be present in patients with subdural hematoma

Tremors.

Abnormal movement and gait can be indicative of Parkinson disease or multiple sclerosis.

Catatonia (grouped into increased, abnormal, and decreased psychomotor behavior): may occur in the context of either a medical or psychiatric disorder.[61]

Initial tests

The aim of initial tests is to identify patients with an organic cause, as well as exclude the most common organic causes. All patients require:

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be considered as a screen for possible autoimmune disorders

CBC to evaluate for anemia or infection

Glucose to rule out hypo- or hyperglycemia

Liver function tests (including gamma-GT)

Parathyroid hormone and calcium

Serum electrolytes and creatinine to evaluate kidney function

STI testing, including HIV and syphilis

Thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4)

Urine drug screen

Vitamin B12, thiamine, niacin, and folate levels.

Complete blood count findings are nonspecific. Leukocytosis should prompt suspicion of infection. Serum electrolytes may be abnormal if there is an underlying metabolic or endocrine disturbance. Liver function tests may be abnormal in a range of conditions, including chronic alcohol abuse and Wilson disease. Renal function tests may detect underlying renal failure.

Recreational drugs are the most common secondary cause of psychosis. Urine drug testing is required in all patients to screen for amphetamines, benzodiazepines, cocaine, cannabis, opioids, and phencyclidine. If other hallucinogens are suspected based on the history and clinical features, a blood or hair drug screen may also be necessary. Known causative agents should be discontinued. If symptoms resolve, a diagnosis of drug-induced psychosis can be made retrospectively. Withdrawal syndromes are diagnosed clinically. Blood alcohol levels are useful if alcohol is suspected as being a contributing factor, although a positive result is not diagnostic of alcohol abuse.

Vitamin B12, thiamine, niacin, and folate levels should be measured to exclude nutritional deficiency.

TSH and T4 should be measured to exclude hypo- or hyperthyroidism.

ANA and ESR, although nonspecific, may be useful to screen for autoimmune disorders. If ANA is positive or the ESR is elevated, specific investigations for the suspected disorder should be performed, guided by clinical findings.

Urgent brain imaging is recommended for patients who present with new onset psychosis in the context of features suggestive of an intracranial cause, such as a severe unremitting headache, focal neurologic deficits, or recent head trauma.

Delirium with psychosis: additional initial tests

When a patient presents with delirium with psychosis, a wide range of urgent initial tests need to be performed to identify the underlying cause, including all of the initial blood tests and:

Blood culture

Urinalysis and culture

Chest x-ray.

Patients with suspected Cushing syndrome undergo a 24-hour urinary free cortisol test. Those with suspected hyperparathyroidism require a serum calcium and serum parathyroid hormone test. If porphyria is a consideration, perform a spot urine sample for porphobilinogen during acute attack, and a 24-hour urine for porphyrins, porphobilinogen, and delta-aminolevulinic acid.

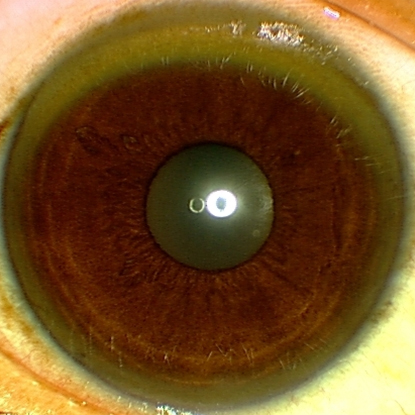

Screening for Wilson disease should be considered in patients with abrupt-onset psychosis. Initial tests include ceruloplasmin, 24-hour urine copper excretion, and a slit-lamp ophthalmologic exam to detect Kayser-Fleischer rings. Other tests include total serum copper, liver biopsy, and genetic investigation of ATP7B.[62]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Eye demonstrating Kayser-Fleischer ringAdapted from BMJ (2009), used with permission; copyright 2009 by the BMJ Publishing Group [Citation ends].

Lysosomal storage diseases require specific diagnostic tests that may include a skin biopsy, genetic tests, and the detection of alpha-galactosidase enzyme in plasma or serum. Homocystinuria is diagnosed using quantitative tests for homocysteine in urine and blood, and molecular genetic testing. Metachromatic leukodystrophy is diagnosed by checking arylsulfatase A enzyme activity in white blood cells or in cultured skin fibroblasts.

Subsequent tests

Further tests are guided by the clinical presentation. In suspected drug toxicity (prescribed or illicit), urine toxicology and blood drug levels may be required. Other tests may include:

Cardiac troponin

ECG

Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time

Serum calcium

Serum creatine kinase

Serum phosphorus.

In addition to recreational drugs and medications, other toxic exposures may be present and should also be excluded if suggested by clinical features. Organophosphate toxicity is a clinical diagnosis (measuring cholinesterase activity in red blood cells correlates with CNS acetylcholinesterase and is a useful marker of organophosphate poisoning but is not readily available). Where heavy metal toxicity is considered, a urine heavy-metal screen is performed.

Patients presenting with extreme malnourishment may have pellagra due to niacin deficiency or Korsakoff psychosis due to thiamine deficiency. Niacin and/or thiamine levels should be measured if these conditions are suspected. An erythrocyte transketolase activity test and a 24-hour urinary thiamine excretion test may also be requested in suspected thiamine deficiency. Where folate deficiency is being considered, serum homocysteine may be measured subsequent to folate and serum vitamin B12 tests. The following tests may also be performed, having checked the serum niacin level, if deficiency is suspected: serum tryptophan, serum nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and serum nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

HIV testing (if HIV neurologic complications are suspected) and a treponemal test (if neurosyphilis is suspected) should be considered if clinical features suggest the diagnosis, known risk factors are present, or the patient comes from a population where syphilis, HIV, or other STIs are common.

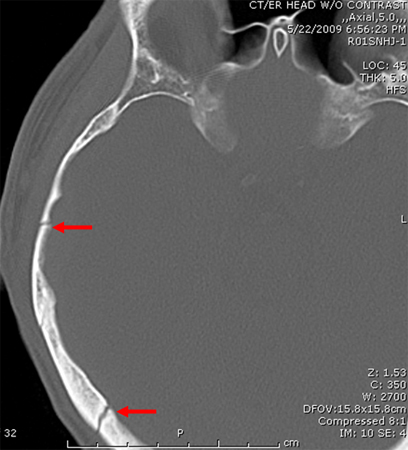

MRI or computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain should be ordered if an organic CNS cause is suspected.[6] Indications for MRI or CT scanning include:

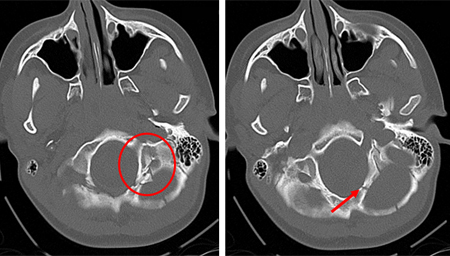

A history of head trauma (to detect intracranial bleeding or hematoma)

Presence of focal neurologic signs

Suspicious headache or change in headache pattern

Late age of onset or pronounced cognitive deficits, suggestive of dementia.

Atypical psychotic symptoms, such as visual hallucinations

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Occipital fracture extending to foramen magnum: risk of brainstem compression by hematoma.From the teaching collection of Demetrios Demetriades, Division of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care, LAC/USC Trauma Center, Keck School of Medicine at USC; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Linear parietal fracture without depressionFrom the teaching collection of Demetrios Demetriades, Division of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care, LAC/USC Trauma Center, Keck School of Medicine at USC; used with permission [Citation ends].

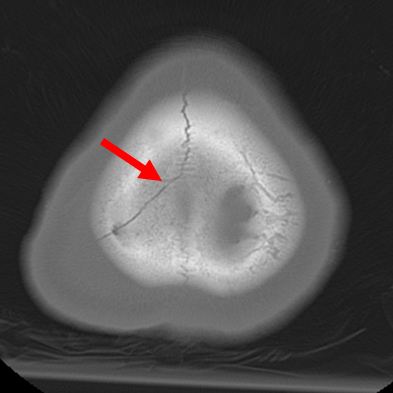

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Linear parietal fracture without depressionFrom the teaching collection of Demetrios Demetriades, Division of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care, LAC/USC Trauma Center, Keck School of Medicine at USC; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fracture of temporal bone.From the teaching collection of Demetrios Demetriades, Division of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care, LAC/USC Trauma Center, Keck School of Medicine at USC; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fracture of temporal bone.From the teaching collection of Demetrios Demetriades, Division of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care, LAC/USC Trauma Center, Keck School of Medicine at USC; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI: T2 and T1 postcontrast, demonstrating a tectal glioma (grade II).From the personal collection of Karine Michaud, University of California, San Francisco; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI: T2 and T1 postcontrast, demonstrating a tectal glioma (grade II).From the personal collection of Karine Michaud, University of California, San Francisco; used with permission [Citation ends].

MRI brain scan with a contrast agent (gadolinium) is used when the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is being considered. A lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid analysis (including a differential cell count, culture, and serology) should also be performed, along with an evoked potentials test, if multiple sclerosis is suspected. Lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be performed if encephalitis is suspected and a mass lesion in the brain has been excluded. CT scan of the chest is useful to diagnose thymoma following a chest x-ray.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI using FLAIR and contrast agent gadolinium showing typical lesions seen in MS in the periventricular regions.From the personal collection of Lael A. Stone, Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation; used with permission [Citation ends].

An EEG should be considered if temporal lobe epilepsy or encephalopathy is suspected. Genetic testing may be indicated in specific situations, such as testing for Huntington disease in people with dementia.

Further investigations in people with suspected Cushing syndrome include blood glucose, low-dose dexamethasone suppression test, evening salivary cortisol, and the dexamethasone-corticotropin-releasing hormone test. People with abnormal thyroid initial tests may be followed up with a free T3 level and thyroid autoantibodies enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antithyroid peroxidase.

Psychiatric evaluation

Psychiatric (i.e., nonorganic) causes of psychosis can be diagnosed once organic causes have been excluded.

A careful psychiatric history is required to diagnose primary psychotic disorders. This should include a detailed mental state exam. DSM-5-TR or ICD-11 diagnostic criteria should be consulted.[2][63] When considering specific diagnoses, such as bipolar disorder, UK guidance recommends that a family member of the patient, or a carer, gives a corroborative history.[64]

UK guidance on psychosis and schizophrenia recommends that people with a first presentation of psychosis should receive a comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment without delay by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other professional with psychiatric expertise.[65] The assessment should cover:[65]

Psychiatric history, including risk of self harm or harm to others, alcohol, and prescribed and nonprescribed drug therapy

Medical history

Current physical health and wellbeing, including weight, smoking, exercise

Relationships (psychological, psychosocial, social networks) and history of trauma

Developmental history

Social history

Occupational and educational history

Quality of life

Economic status.

Schizophrenia:[2]

Based on DSM-5-TR criteria, schizophrenia can be diagnosed if the following conditions are met:

Two or more of the following symptoms are present: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized/catatonic behavior, or negative symptoms. At least one of the symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.

Symptoms occur for a period of at least 1 month (less, if treated) and are associated with continuous signs of the disturbance for at least a 6-month period with functional decline for a significant portion of the time since onset.

Symptoms are not attributable to the effects of a substance or another medical condition and mood disorders with psychotic features have been ruled out.

Schizophreniform disorder:[2]

Based on DSM-5-TR criteria, schizophreniform disorder is characterized by two or more of the following symptoms, present for a considerable part of a 1-month period (less, if treated):

Delusions

Hallucinations

Disorganized speech (e.g., frequent derailment or incoherence)

Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

Negative symptoms.

At least one of the symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.

An episode lasts at least 1 month but less than 6 months.

Schizoaffective disorder and depression or bipolar disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out, and the symptoms are not attributable to the effects of a substance or other medical condition.

Schizoaffective disorder:[2]

Based on DSM-5-TR criteria, schizoaffective disorder debut has an uninterrupted period of illness, during which there is an episode of mood disorder (manic or major depressive disorder) concurrent with two or more of the following symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized/catatonic behavior, or negative symptoms. At least one of the symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.

During the lifetime period of illness, there are delusions or hallucinations for 2 or more weeks, in the absence of prominent mood symptoms.

Mood symptoms have been present for the majority of the total duration of the active and residual period of illness.

Other possible etiologies such as substances (e.g., drug abuse, medication) or other medical conditions have been ruled out.

Brief psychotic disorder:[2]

Psychotic symptom(s)

The presence of one or more of the following symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, or grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior. At least one of the symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.

Duration of episode

For at least 1 day, but <1 month, before a full return to pre-morbid level of functioning.

Not better accounted for by other etiologies

e.g., another medical condition, the direct physiological effects of a substance (drug misuse or medicine), a mood disorder with psychotic features or another psychotic disorder.

Delusional disorder:[2]

Delusions of at least 1 month's duration.

The patient has never met the criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Hallucinations, if present, are related to the delusional theme and are not prominent.

Apart from the impact of the delusions or its ramifications, functioning is not markedly impaired and behavior is not obviously odd or bizarre.

If mood episodes have occurred, these have been brief relative to the duration of the delusional periods.

The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition and is not better explained by another mental disorder.

Bipolar disorder:

DSM-5-TR classifies bipolar disorder separately from the depressive disorders, the schizophrenia spectrum, and other psychotic disorders.[2] A diagnosis of bipolar I disorder requires there to have been a manic episode, which may have been preceded or followed by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. A manic episode lasts for at least 1 week and is defined as a period of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and persistently increased activity or energy with specific features that represent a change to normal behavior.[2]

Three or more of the following features (or four if the mood is only irritable) are present:

Inflated self-esteem

Change in sleep pattern: the patient reports needing significantly fewer hours of sleep to feel rested

Speech is pressured for most conversations

Flight of ideas and patient reports thoughts coming too fast to keep up with

Distractibility

Increased goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation

Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences.

People with bipolar I disorder have marked functional impairment during the manic episode, which is not due to any other medical disorder or substance and which may require hospitalization or have psychotic features. Major depressive episodes are common but not required for diagnosis of bipolar I disorder.

People with bipolar II disorder have never had a full manic episode; but may be diagnosed after at least one hypomanic episode and at least one major depressive episode. Hypomanic episodes last ≥4 days and are present most of the day, nearly every day. There is an unequivocal change in functioning during this period, observable by others, not due to any other medical condition or substance. Functional impairment however is not marked and there is no psychosis during the hypomanic episode.[2]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer