Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Think 'Could this be sepsis? based on acute deterioration in an adult patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[65][66][67] See Sepsis in adults.

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis.[65][67][68][69]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis.

Make the patient nil by mouth and start intravenous fluids. Check local protocols for specific recommendations on fluid choice.

UK guidelines recommend replacing fluid losses volume for volume using Hartmann’s solution (Ringer’s lactate/acetate solution) according to body weight. An intravenous physiological saline with appropriate additions of potassium can be used as an alternative.[70]

Consider referring patients with profound volume disturbance to the critical care unit.

In patients with significant abdominal distention and repeated vomiting or who are at high risk of aspiration, place a nasogastric tube for decompression of the gut.[6]

Treat any underlying cause such as intra-abdominal infections or other acute/systemic illnesses.

Reduce or discontinue pharmacological agents (e.g., opioids, anticholinergics) that slow gastrointestinal motility and can cause ileus.

Correct any electrolyte imbalance, particularly hyper-magnesaemia, which has been associated with ileus.[59] Electrolytes should be monitored and corrected as necessary.

In patients with prolonged postoperative ileus (lasting 4 days or longer post-surgery), start parenteral nutrition in those who do not have any oral intake for more than 7 days.[6][35]

Make the patient nil by mouth and start intravenous fluids. Check local protocols for specific recommendations on fluid choice.

UK guidelines recommend replacing fluid losses volume for volume using Hartmann’s solution (Ringer’s lactate/acetate solution) according to body weight. An intravenous physiological saline with appropriate additions of potassium can be used as an alternative.[70]

Consider referring patients with profound volume disturbance to the critical care unit.

Monitor electrolytes and replace as necessary.

Electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalaemia, hypo-chloraemia, alkalosis, and hyper-magnesaemia) may be a consequence of ileus or an exacerbating factor.[59]

Practical tip

Think 'Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in an adult patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[65][66][67] See Sepsis in adults.

The patient may present with non-specific or non-localised symptoms (e.g., acutely unwell with a normal temperature) or there may be severe signs with evidence of multi-organ dysfunction and shock.[65][66][67]

Remember that sepsis represents the severe, life-threatening end of infection.[71]

It is important to distinguish between small bowel obstruction and ileus; small bowel obstruction may progress to a more serious condition with bowel ischaemia if there is a twist of the intestines or vascular compromise. Ischaemic bowel disease and bowel perforation can cause rapid deterioration into septic shock.[69] In practice, if computed tomography shows extensive ischaemia in a patient who is very frail or has significant comorbidities, palliative care may be the treatment of choice (rather than antibiotics and source control); this decision should always be made in discussion with a consultant.

Use a systematic approach (e.g., National Early Warning Score 2 [NEWS2]), alongside your clinical judgement, to assess the risk of deterioration due to sepsis.[65][66][68][72] Consult local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution.

Arrange urgent review by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis:[69]

Within 30 minutes for a patient who is critically ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 7 or more, evidence of septic shock, or other significant clinical concerns)

Within 1 hour for a patient who is severely ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 5 or 6).

Follow your local protocol for investigation and treatment of all patients with suspected sepsis, or those at risk. Start treatment promptly. Determine urgency of treatment according to likelihood of infection and severity of illness, or according to your local protocol.[69][72]

In the community: refer for emergency medical care in hospital (usually by blue-light ambulance in the UK) any patient who is acutely ill with a suspected infection and is:[67]

Deemed to be at high risk of deterioration due to organ dysfunction (as measured by risk stratification)

At risk of neutropenic sepsis.

Place a nasogastric (NG) tube for decompression of the gut in patients with significant abdominal distention and repeated vomiting or who are at high risk of aspiration.[6]

The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) guidelines recommend against the placement of a NG tube during surgery as a routine measure.[28] Studies have shown that routine NG decompression is unnecessary and may be detrimental. Therefore, routine NG decompression is reserved for selective use.[28][73] Often, orogastric decompression is performed intra-operatively, but the tube is removed at the completion of surgery.[28]

Measure gastric output and replace lost volume using Hartmann’s solution (Ringer’s lactate/acetate solution) according to body weight. An intravenous physiological saline with appropriate additions of potassium can be used as an alternative.[70]

Assess the patient for absence of abdominal distention, decreasing NG tube output, and passage of flatus and stool, with a view to removing the NG tube.

The decision to remove the NG tube is based on measured gastric output over time and clinical resolution of ileus. A trial of spigotting (i.e., blocking) the NG tube to test whether the gastrointestinal tract is patent and working is sometimes used to avoid taking it out too soon.

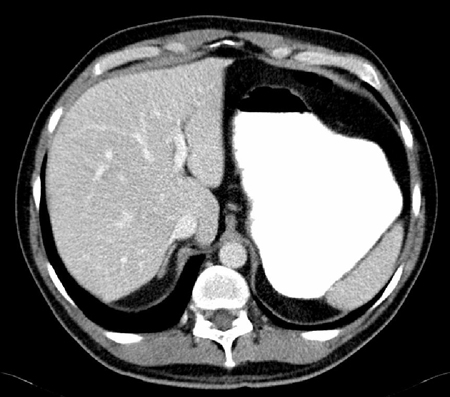

If the patient displays evidence of ongoing ileus with abdominal distention and vomiting, reinsert the NG tube. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nasogastric tubeFrom the personal collection of Dr Paula I. Denoya [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing significantly dilated stomach [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing significantly dilated stomach [Citation ends].

In patients undergoing surgery and requiring opioid analgesia, decreasing the use of systemically administered opioid analgesics is recommended through the use of multimodal anaesthesia and analgesia techniques. For example, using adjuncts such as paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ketorolac, and analgesics and local anaesthetics administered via epidural.[27][28][31][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][44][45][46][47] The use of epidural analgesia helps to prevent postoperative ileus, although in practice can be challenging due to its impact on the patients' mobility.[28][33][34][35] For more information on perioperative measures to prevent postoperative ileus, see Prevention.

Once ileus begins to resolve, as seen by passage of flatus and resolution of abdominal distention and nausea, the patient can be started on a liquid diet and advanced as tolerated.

The passage of flatus or stool and tolerance of an oral diet has been shown to be the best clinical endpoint of postoperative ileus.[3][4]

More info: Other evaluated therapies

In patients with acute small bowel obstruction as a result of adhesions, an oral water-soluble contrast challenge may help estimate whether conservative treatment has been successful. Patients in which the contrast reaches the colon by 24 hours rarely require surgery.[74][75][76] There is debate and controversy, however, around the use of oral water-soluble contrast to treat adhesive small bowel obstruction.[77][78][79] Two small double-blind placebo-controlled trials of patients with prolonged postoperative ileus after elective colorectal surgery suggest that a water-soluble contrast agent such as Gastrografin® (meglumine diatrizoate/sodium diatrizoate solution) is of limited clinical utility in these patients.[6][80][81]

Pro-motility agents have been used to treat ileus with limited success.[82] While metoclopramide is helpful in treating delayed gastric emptying, it has not proved useful in postoperative ileus when evaluated in randomised controlled trials.[52][83][84] Intravenous erythromycin has been found not to be beneficial for the treatment of postoperative ileus.[52][85][86] The evidence is insufficient to recommend the use of cholecystokinin-like drugs, cisapride, dopamine agonists, propranolol, or vasopressin.[82]

Prolonged postoperative ileus (lasting 4 days or longer post-surgery)

Give parenteral nutrition to patients who do not have any oral intake for more than 7 days.[6][35] Consult with a dietitian as it is important to avoid refeeding syndrome, which can be fatal in patients with malnutrition.

Patients with prolonged postoperative ileus (lasting 4 days or longer post-surgery) may be nil by mouth for several weeks.

The benefits of starting parenteral nutrition earlier than 7 days are outweighed by the risks associated with parenteral nutrition and central venous access. In most patients, the postoperative 'starvation' state is not associated with increased morbidity or mortality. Insertion of a central venous line is associated with increased risk of iatrogenic injury to nearby vessels, pneumothorax, deep vein thrombosis, and central line-associated bacteraemia.

Check electrolytes, including phosphate, daily to identify electrolyte abnormalities associated with postoperative intravenous feeding and the nil by mouth status, and correct any imbalances.

Treat any underlying condition, such as sepsis, intra-abdominal infections, or other acute/systemic illnesses associated with intestinal hypomotility such as diabetes mellitus, Chagas disease, scleroderma, and neurological diseases.

Reduce or discontinue pharmacological agents (e.g., opioids, anticholinergics) that slow gastrointestinal motility and can cause ileus. Correct any electrolyte imbalance, particularly hyper-magnesaemia, which has been associated with ileus.[59]

How to insert a fine bore nasogastric tube for feeding.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer