Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Suspect postoperative ileus in a patient who develops abdominal distention, abdominal pain, no flatus or bowel movements, and vomiting approximately 2 or 3 days after undergoing major abdominal surgery.[6][53]

Ileus is a slowing of gastrointestinal motility that is not associated with mechanical obstruction. Most patients presenting with ileus will have recently undergone surgery, usually gastrointestinal, but ileus can also manifest from non-gastrointestinal surgery (e.g., thoracic, cardiac, or extremity) or from other retroperitoneal pathology such as aortic or urinary disorders.[6]

Order a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast according to local hospital protocols to differentiate prolonged ileus (lasting 4 days or longer post-surgery) and mechanical obstruction or other intra-abdominal complications (e.g., anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery, intra-abdominal abscess).[54]

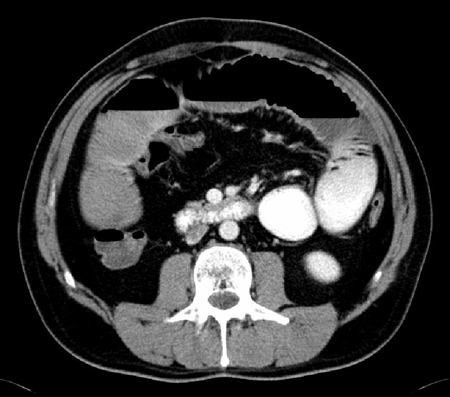

In ileus, a CT scan shows distention of the stomach, fluid filled intestines, and no evidence of a transition point between dilated and collapsed bowel (a key indicator of obstruction) or of other major complications of surgery.

In patients with prolonged ileus, a small bowel series using oral water-soluble contrast may be done to evaluate for any evidence of mechanical obstruction that may have been missed on the CT scan.

Symptoms and signs of ileus include:[6]

Nausea and vomiting

Constipation (which may be severe)

Failure to pass flatus

Abdominal distention

Discomfort from gaseous distention, usually with pain.

Suspect postoperative ileus in a patient who develops abdominal distention, no flatus or bowel movements, and vomiting approximately 2 or 3 days after major abdominal surgery.[6][53]

Most patients presenting with ileus will have recently undergone surgery, usually gastrointestinal, but ileus can also manifest from non-gastrointestinal surgery (e.g., thoracic, cardiac, or extremity) or from other retroperitoneal pathology such as aortic or urinary disorders.[6]

Differentiate postoperative ileus from postoperative small bowel obstruction. The clinical features of ileus and small bowel obstruction can be very similar.[55] See Differentials and Small bowel obstruction.

Consider a prolonged ileus or persistent obstruction if the patient fails to eat, pass flatus, or evacuate their bowel on or after day 4 post-surgery.[6][7]

In general, if the patient has already passed flatus or stool and then ceases to do so, an obstruction may be a more likely cause than a prolonged postoperative ileus.[55] However, note that there are cases where a mechanical element such as a small bowel obstruction progresses to a clinical picture more consistent with ileus.[6]

Practical tip

Patients who have postoperative small bowel obstruction can be easily misdiagnosed as having ileus. Remember that ileus is a paralytic failure of gut motor function that usually requires a significant insult to induce it. Gut motor function returns rapidly (usually within 3-4 days) even after major abdominal surgery, unless there are any co-existing major inflammatory or infective complications.[7]

Take a careful history.

Ask about onset and note the duration of the patient’s symptoms:

Postoperative ileus presents approximately 2 or 3 days after surgery and usually resolves within 3 to 4 days.[6][7] Resolution is signalled by the passage of stool or flatus and tolerance of an oral diet.[3][4]

In some patients, prolonged postoperative ileus develops, which is defined as two or more of the following occurring on or after day 4 post-surgery without prior resolution of postoperative ileus:[6][7]

Vomiting

Abdominal distension

Inability to tolerate oral feeding

Absence of flatus.

Ask about the nature of their symptoms:

Failure to pass stools or flatus

Decreased flatus and passage of stool is a common finding. However, the presence of bowel movements or ‘discharge’ (passage of liquid stool or mucus) does not exclude ileus.

Abdominal pain

Discomfort from gaseous distention is common, with pain. Cramping or colicky pain are unusual in ileus; when present they indicate gut muscle activity.

Abdominal distention or tenderness

Present in 71% of patients with postoperative ileus.[35]

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea is present in almost all patients.

When vomiting is present, it may be an indication for placement of a nasogastric tube for decompression.

Ask about risk factors, including:

Recent surgery, particularly if using invasive surgical techniques

Most patients presenting with ileus will have recently undergone surgery (usually abdominal surgery, but ileus can present following non-abdominal surgery, such as thoracic, cardiac, or extremity).

The stress responses to incision of the peritoneum and bowel manipulation, postoperative factors such as immobilisation, use of analgesics (e.g., opioids), pain, and slow resumption of oral diet, and to a lesser extent general anaesthesia, can all contribute to the development of ileus.

Using invasive surgical techniques (such as laparotomy) and performing longer operations (i.e., the degree of surgical manipulation of the bowel) are both major risk factors for developing ileus.[28] This is mitigated by using minimally invasive surgical techniques (e.g., laparoscopy) whenever possible.[28] For more information on perioperative measures to help prevent postoperative ileus, see Prevention.

History of recent acute and systemic conditions (e.g., myocardial infarction, pneumonia, acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis, sepsis, multi-organ trauma)[29][30]

Current medication

Opioid-based analgesics interfere with gastrointestinal motility. This often manifests as severe constipation, but may also present as ileus.

Some anticholinergic agents (e.g., atropine) affect motility, contributing to the development of postoperative ileus.[31]

Comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular insufficiency, scleroderma)

Gastroparesis in diabetes mellitus, and intestinal ischaemia associated with cardiovascular insufficiency, can contribute to gastrointestinal motility disorders due to the low blood flow. Autoimmune diseases, such as scleroderma, are associated with motility disorders and may exacerbate ileus.

Check for signs of dehydration such as tachycardia and hypotension, and assess pain.

Patients may be hypovolaemic or may be haemodynamically unstable due to other co-existing complications contributing to ileus.

Hypovolaemia may manifest as low urine output (normal urine output for an adult is above 0.5 mL/kg/hour) and is a common finding. In severe cases, there may be a significant fluid shift into an inert small bowel.

An increasing amount of pain or opioid requirement is a sign that the patient may have an acute bowel obstruction or other intra-abdominal disease rather than ileus. Colicky pain points to an obstruction rather than to ileus.

Examine the patient’s abdomen.

Palpate for any tenderness and look for distension

Distension or tenderness is present in 71% of patients with postoperative ileus.[35]

Look for any evidence of:

Mechanical obstruction such as hernias or mass. See Small bowel obstruction and Large bowel obstruction.

Peritoneal inflammation, such as peritonitis and tenderness. This is an unusual finding and points to other intra-abdominal disease processes, which may be contributing to or mimicking postoperative ileus.

There may be decreased bowel sounds. These are non-specific but a typical finding in ileus.

Order a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis using oral water-soluble contrast and intravenous contrast, according to local hospital protocols. This is to distinguish prolonged ileus (lasting 4 days or longer post-surgery) from mechanical obstruction or other intra-abdominal complications (e.g., anastomotic leak in colorectal surgery, abdominal abscess), which can cause a secondary ileus.[54][56][57]

Check the patient’s kidney function, as acute kidney injury may be a contraindication to a CT scan using a contrast agent.[58]

In ileus, the CT scan shows distention of the stomach, fluid filled intestines, and no evidence of a transition zone between dilated and collapsed bowel (a key indicator of obstruction).

It is important to distinguish between small bowel obstruction and ileus; small bowel obstruction may progress to a more serious condition with bowel ischaemia if there is a twist of the intestines or vascular compromise.

In postoperative patients, a CT scan should be performed if the presumed ileus has not resolved in 3 to 4 days, or if the clinical condition of the patient worsens.

Practical tip

In general, do not use plain radiography of the chest and abdomen to differentiate prolonged ileus and mechanical obstruction.

In cases of prolonged ileus, a small bowel series using oral water-soluble contrast may be done to evaluate for any evidence of mechanical obstruction that may have been missed on CT scan.

Consider performing a gastric emptying study in cases of prolonged ileus, especially in patients with comorbidities such as long-standing diabetes mellitus, which is associated with autonomic neuropathy.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan with intravenous and oral contrast showing fluid-filled small intestine and caecum in ileus [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan with intravenous and oral contrast showing fluid-filled small intestine in ileus [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan with intravenous and oral contrast showing fluid-filled small intestine in ileus [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel series showing dilated small bowel loops in ileus; nasogastric tube is seen curled in the stomach [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel series showing dilated small bowel loops in ileus; nasogastric tube is seen curled in the stomach [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel series showing dilated contrast-filled small bowel loops in ileus; some contrast is visible in the right colon [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel series showing dilated contrast-filled small bowel loops in ileus; some contrast is visible in the right colon [Citation ends].

Perform the following blood tests:

Full blood count

To evaluate for evidence of infection. A significantly elevated WBC, especially if accompanied by abdominal tenderness or peritoneal signs, is a sign that a more severe condition (e.g., sepsis, peritonitis) is present.

Electrolytes

Ileus and obstruction may be accompanied by hypokalaemia and hypo-chloraemia. Hyper-magnesaemia may be present.

Check electrolytes daily, including phosphate, in patients on parenteral nutrition to identify any electrolyte abnormalities associated with postoperative intravenous feeding and the nil by mouth state.

Urea and creatinine

Elevated urea and creatinine may be present in dehydrated patients.

Arterial blood gases

To evaluate for the presence of acid base disturbance. Metabolic alkalosis may be present in dehydrated states, and acidosis may be present in intestinal ischaemia.

Liver-function tests and lipase and amylase

To check for other, non-surgical, causes of ileus, such as pancreatitis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer