Approach

Eosinophilia may be an incidental finding in a patient who is not particularly unwell. If there is a history of allergy (e.g., asthma, hay fever, seasonal rhinitis) and the count is only mildly elevated (e.g., 0.6 × 10⁹/L to 1.5 × 10⁹/L [600-1500/microlitre]), further investigation is not usually indicated. If the patient has a skin condition known to be associated with eosinophilia (e.g., urticaria, eczema, pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, or pemphigoid gestationis), no further investigation of the eosinophilia is indicated (other than what is needed for the effective management of the condition).

If the patient is unwell or the count is significantly elevated and the cause is not clear, investigation is indicated. Sometimes such investigation is urgent (e.g., in cardiac failure or if the eosinophil count is extremely high).

History

The medical history of a patient with eosinophilia should first involve evaluation of the presenting complaint, followed by a systematic review.

Allergy

A history of hay fever, eczema, asthma, or urticaria should be sought.

Geographic factors

Residence in or travel to an area where parasitic infestation or coccidioidomycosis is endemic should be ascertained.

If the patient has lived in or travelled to a tropical region, he or she should be questioned about exposure to soil or freshwater and about any symptoms suggestive of parasitic disease during the visit.

All travel experiences (not only recent) are important (e.g., strongyloidiasis can present many decades after leaving an endemic area, particularly when immunity is suppressed).

HIV infection

Risk factors for HIV infection should be sought, because HIV-positive patients are more likely to have disseminated parasitic or fungal infections that promote eosinophilia.

Drug history

A drug history should be taken (particularly of non-prescription drugs, newly-given drugs [usually started 2-6 weeks previously], and immunosuppressive drugs).

A history of recent administration of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents is relevant, because immunosuppressive treatment may lead to hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis.

It should be noted whether the patient is taking any drugs often associated with adverse reactions (e.g., sulfonamides, cephalosporins, penicillin, nitrofurantoin, carbamazepine, allopurinol, phenytoin, or gold). Fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, and impaired liver function tests may indicate an adverse drug reaction.

History of rash or lymphadenopathy

Relevant, not only in relation to a drug reaction but also to primary skin diseases that can cause eosinophilia. Leukaemia, lymphoma, or systemic mastocytosis can all cause both a rash and lymphadenopathy.

Cardiac history

Cardiac symptoms (e.g., dyspnoea, chest pain, palpitations) in a patient with marked or prolonged eosinophilia could indicate cardiac damage by eosinophil products. Eosinophilic cardiac disease is a clinically urgent situation.

Other organ-related symptoms

Symptoms related to specific organ systems may indicate a particular inflammatory disease, such as dysphagia in eosinophilic oesophagitis, or abdominal pain and diarrhoea in eosinophilic gastroenteritis.[12][13][14][15]

Symptoms of lymphoma

Fever, night sweats, weight loss, itch, and alcohol-induced pain, all possible symptoms of lymphoma, should be specifically enquired about.

Episodic symptoms

Symptoms such as episodic weight gain and episodic angio-oedema should be sought, as they occur in the rare condition of Gleich's syndrome (episodic angio-oedema with eosinophilia).

Physical examination

Patient temperature should be recorded. Fever may indicate parasitic or fungal infection, or a drug reaction.

The skin should be examined for erythema, eczematous rash, oedema, urticaria, or skin infiltration. This could indicate primary skin disease, a drug reaction, some parasitic infections, eosinophilic leukaemia, urticaria pigmentosa associated with systemic mastocytosis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, or cyclical angio-oedema with eosinophilia.

Signs of vasculitis or peripheral ischaemia should be looked for. These could indicate a primary vasculitic condition such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome) or be a feature of hypereosinophilia itself, in either case indicating possible clinical urgency.

Bronchospasm can be a feature of asthma, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, or a severe drug reaction. Other respiratory symptoms (such as cough, dyspnoea, or wheeze) could indicate a lifecycle-related pulmonary migration of parasites, a drug reaction, or eosinophilic leukaemia. Schistosomiasis can cause pulmonary hypertension, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis can cause pulmonary infiltrates.[16]

All lymph node areas should be examined for lymphadenopathy. If nodes are enlarged, the size and texture of the nodes should be assessed, because this may suggest a possible neoplasm (e.g., lymphoma or either lymphoid or myeloid leukaemia): hard, fixed, non-tender nodes are more likely to be due to malignancy.

Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly may be features of lymphoma or eosinophilic leukaemia.

Cardiomegaly, arrhythmia, or cardiac failure may indicate cardiac damage by eosinophils and a clinically urgent situation.

Neuropathy could indicate damage by eosinophil proteins.

Investigations

Full blood count (FBC) should be done to confirm eosinophilia and to document the eosinophil count. The FBC and blood film should also be used to look for:[17]

Evidence of underlying haematological malignancy (e.g., blast cells, neutrophilia with left shift, monocytosis, basophilia, dysplastic features, and lymphoma cells)

Thrombocytosis, which may occur secondary to infection, inflammation, haemorrhage, or malignancy, as well as in certain haematological disorders (such as chronic myeloid leukaemia, essential thrombocythaemia, and polycythaemia vera)

Evidence of parasite infection (e.g., presence of microfilariae).

It should be noted that cytological abnormalities of eosinophils can be marked in reactive eosinophilia as well as in eosinophilic leukaemia, so are not often useful in indicating a likely eosinophilic leukaemia.[18]

If parasitic infection is suspected:

Stool specimens should be examined for ova, cysts, and parasites on three separate occasions. This is extremely useful in looking for evidence of clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis, schistosomiasis, hookworm infestation, ascariasis, and strongyloidiasis.[19]

Serology can test for strongyloidiasis, schistosomiasis (especially if there has been travel to or residence in Africa), filariasis (particularly in West Africa), toxocariasis, cysticercosis, echinococcosis, angiostrongyloidiasis, and gnathostomiasis.[20]

Examination of the urine is the main method for detecting Schistosoma haematobium.

Examination of sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, or endoscopy may be needed to identify parasites in some clinical settings.

Coccidioidomycosis should be looked for after travel in California or Arizona. It can be identified by serology, but more than one diagnostic test is recommended because current evidence does not support a single best test.[21] Chest x-ray (CXR) may show a lobar pneumonia, and sputum microscopy and culture may identify the organism. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be raised.[22]

If malignancy is suspected:

Further testing is dictated by the clinical picture. Leukaemias are diagnosed with a combination of findings on blood film, analysis of bone marrow, and other tests specific for different types and subtypes.

Diagnosis of eosinophilic leukaemia associated with rearrangement of PDGFRA or PDGFRB is important because of their sensitivity to therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.[23][24] It should be noted that rare patients with PDGFRA rearranged, and a significant proportion of patients with PDGFRB rearranged, do not have hypereosinophilia, so a normal eosinophil count cannot be used to exclude these conditions.[25]

Specific drugs for the management of eosinophilic leukaemia associated with rearrangement of FGFR1 are also becoming available, so this diagnosis may also be important.[26]

A definitive diagnosis of lymphoma is made by lymph node excision biopsy.

If the differential diagnosis includes systemic mastocytosis or chronic eosinophilic leukaemia, then serum tryptase should be requested.[17]

Skin disease

Pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid both have their own characteristic findings on skin biopsy, and can be identified by immunofluorescence and antibody studies. Immunofluorescence studies of skin biopsy or serum will confirm a diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis.

Allergic/immune mediated disease

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is associated with raised IgE levels. An Aspergillus skin test typically reveals an immediate cutaneous hypersensitivity. CXR may show pulmonary infiltration, and a high-resolution computed tomography scan of the chest will show central bronchiectasis and sometimes mucous plugging with bronchoceles.[27]

In eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, CXR may show reticulonodular infiltration, a pleural effusion, and lymphadenopathy. On sinus x-rays, typical findings of sinusitis are common (opacification of involved sinuses, mucosal thickening, air-fluid levels, or anatomical abnormalities). There is usually a normocytic normochromic anaemia in addition to the eosinophilia, and ESR and C-reactive protein are elevated. Other non-specific findings can include positivity for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor, and elevated levels of immunoglobulins, particularly IgE. A necrotising vasculitis with eosinophil infiltration and sometimes granuloma formation is seen on biopsy of affected tissue.[28][29]

Gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy is necessary for the diagnosis of eosinophilic oesophagitis and eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

Marked eosinophilia (>1.5 x10⁹/L [>1500/microlitre])

A marked eosinophilia, particularly eosinophilia >3.0 × 10⁹/L (>3000/microlitre), normally suggests:

Parasitic infection

Drug hypersensitivity

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Hodgkin's lymphoma

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Eosinophilic leukaemia

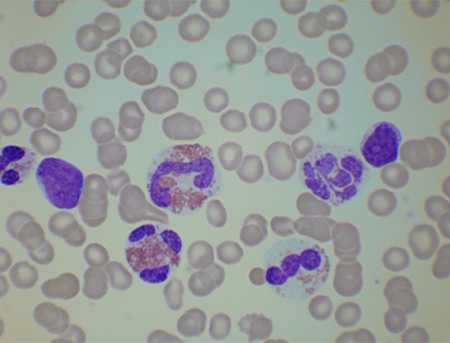

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Blood film from a patient with reactive eosinophilia occurring as a response to acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. There is 1 blast cell. Eosinophils are cytologically abnormalFrom the personal collection of Barbara J. Bain, MBBS, FRACP, FRCPath; used with permission [Citation ends].

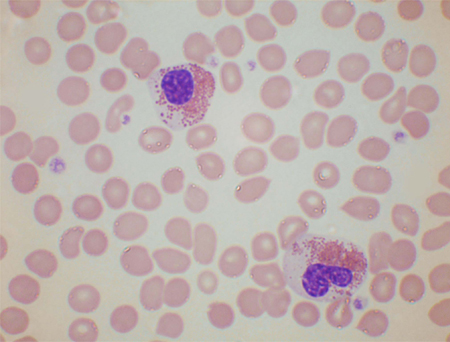

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Blood film from a patient with chronic eosinophilic leukaemia resulting from a FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene. The eosinophils are partly degranulated and one is hypolobatedFrom the personal collection of Barbara J. Bain, MBBS, FRACP, FRCPath; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Blood film from a patient with chronic eosinophilic leukaemia resulting from a FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene. The eosinophils are partly degranulated and one is hypolobatedFrom the personal collection of Barbara J. Bain, MBBS, FRACP, FRCPath; used with permission [Citation ends].

A cut-off point of 1.5 × 10⁹/L (1500/microlitre) has traditionally been taken as 1 criterion for defining the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Other criteria include eosinophilia for >6 months and evidence of organ damage, with no other cause of the eosinophilia found.[2][24] The same cut-off figure of 1.5 × 10⁹/L (1500/microlitre) has been used as part of the definition of chronic eosinophilic leukaemia.[30][31]

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome should not be diagnosed until all identifiable causes have been excluded. If marked eosinophilia (e.g., ≥1.5 × 10⁹/L [1500/microlitre]) gives rise to tissue damage and common causes of eosinophilia have been excluded, excluding all rare causes becomes relevant as well, because some of these are life-threatening and require specific treatment.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer