Approach

In most patients a history and physical examination is sufficient to make a diagnosis, although imaging techniques are useful in certain cases.

History

Patients typically note the insidious onset of an ill-defined ache localised to the anterior knee behind the patella. Occasionally, the pain may be centred along the medial or lateral patellofemoral joint and retinaculum. Pain is typically aggravated with activities that increase patellofemoral compressive forces, such as ascending and descending hills or stairs, running, squatting, and prolonged sitting with the knee in a flexed position.[5][23]

Physical examination

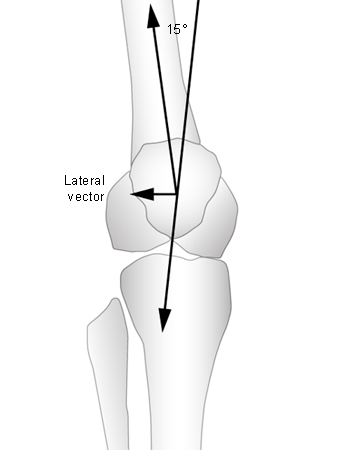

There is no single confirming test and, as the condition has a multi-factorial aetiology, a diagnosis should only be made following multiple physical tests yielding a cluster of positive examination tests.[24] A complete examination of the knee should be performed, including a careful assessment of the patellofemoral joint.[23] The Q angle, which is a measure of the patellar tendency to move laterally when the quadriceps muscles are contracted, should be measured to determine whether this is within the normal range. The Q angle is formed by the line connecting the anterosuperior iliac spine to the centre of the patella and the line connecting the centre of the patella to the middle of the anterior tibial tuberosity. Clinical Q-angle measurement is highly sensitive to error, and there is disagreement on its reliability and validity.[25] In a study in 150 normal asymptomatic knees, the average Q angle in a supine position with the knee extended was 15°, with significant differences according to the patient’s sex showing an average value of 14 ± 3° in men and 17 ± 3° in women (P ≤0.001).[26][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Q angleCreated at BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

Gentle palpation of the lateral and medial patellar retinacula may detect the location of obvious pain sources. With the knee in full extension, portions of the lateral and medial knee retinacula are palpated gently to see whether there is an obvious source of pain. The patella should be displaced medially and laterally to see whether this is painful. Evaluation should also include palpation of the vastus lateralis tendon insertion into the proximal patella. The proximal deep lateral retinaculum interdigitates with the dense insertion of the vastus lateralis into the patella.[27][28] Several studies have presented evidence of nerve damage and hyperinnervation into the lateral retinaculum in patients with patellofemoral malalignment.[29][30][31][32]

Patellar tilt tests should be performed to assess medial and lateral tilt.[33][34][35] There are 2 methods for evaluating patellar tilt:

In the supine position, the test is performed with the knee extended and the quadriceps relaxed. The examiner places his or her thumb and index finger on the medial and lateral border of the patella.[33] If the digit palpating the medial border is more anterior than that on the lateral border, then the patella is tilted laterally. If the digit palpating the lateral border is more anterior than that on the medial border, then the patella is tilted medially.

The knee is extended, the patella is grasped between the thumb and forefinger, and the medial aspect of the patella is compressed posteriorly while the lateral aspect is elevated.[34] If the lateral aspect of the patella is fixed and cannot be raised to at least the horizontal position, then the test is positive and indicates tight lateral structures.

Mediolateral glide, patellar mobility, patellar apprehension, and patellar tracking tests should also be performed:

Mediolateral test

The mid-patella point is first determined by visual assessment, then a tape measure should be used to measure the distance from the mid-patella to the lateral femoral epicondyle and the distance from the mid-patella to the medial femoral epicondyle.[33]

The patella should be sitting equidistant (±5 mm) from each epicondyle when the knee is flexed to 20°.

A 5 mm lateral displacement of the patella causes a 50% decrease in vastus medialis oblique tension.[36]

Patellar mobility test

The patellar mobility test measures passive patellar mediolateral range of motion from the patellar resting position, and indicates the integrity and tightness of the medial and lateral restraints.

The test should be performed with the knee flexed 20° to 30° and the quadriceps relaxed (e.g., resting the knee over the examiner's thigh or with a small pillow underneath the knee).

The patella is divided into 4 longitudinal quadrants, and then the patella is displaced in a medial direction and then a lateral direction using index finger and thumb.[37]

There is an association between patellar hypomobility and a tight iliotibial band.[15]

Lateral patellar mobility of 3 quadrants suggests an incompetent medial restraint. Medial mobility of only 1 quadrant is consistent with a tight lateral restraint, and medial mobility of 3 or more quadrants suggests a hypermobile patella.

Hypermobility with lateral patellar glide is correlated with laxity of the medial patellofemoral ligament or the patellomeniscal ligament and is often noted in association with patellar subluxation.[13][14]

Patellar apprehension test

The thumbs of both hands are used to press on the medial side of the patella, to exert lateral pressure on the medial side of the patella, with the patient's knees flexed about 30° and quadriceps relaxed.

The leg is allowed to project over the side of the examining table and is supported with the knees at 30° of flexion by resting the leg on the thigh of the examiner, who sits on a stool. In this position the examiner can almost dislocate the patella over the lateral femoral condyle.[38]

The patient becomes uncomfortable and apprehensive as the patella reaches the point of maximum passive displacement, with the result that they begin to resist and attempt to straighten their knee, pulling the patella back into a relatively normal position.

This test can be unreliable if the patient is truly apprehensive.

Patellar tracking test

Dynamic patellar tracking measures patellar instability.

The examiner should ask the seated patient to extend the knee from 90° to full extension, and observes the movement pattern of the patella from the front.

In most people, the patella seems to move straight proximally, with a slight lateral shift near terminal extension.

The term 'J sign' describes the path of the patella with maltracking. Instead of moving superiorly with knee extension, the patella suddenly deviates laterally at terminal extension as it exits the trochlear groove to create an inverted J-shaped path.[39][40]

Further physical examinations include tests for muscle flexibility (quadriceps, hamstring muscle, and iliotibial band) and muscle weakness (e.g., using functional performance tests).

The lack of significant findings on physical examination (i.e., normal patellar mechanics, normal lower-extremity function) suggests that the source of patellofemoral pain may be related to overuse and peripatellar synovitis.[41] If there is evidence of significant joint effusion and no history of overuse or trauma, then one must consider potential rheumatological causes of joint inflammation.

Imaging

An x-ray of the knee is used as an adjunct to history and physical examination to provide further information on patellar positioning, or where the clinical examination suggests osteoarthritis; it is the initial imaging study that should be performed.[42] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee without intravenous contrast is indicated when radiography findings are negative and/or further information is needed to evaluate for meniscal tear, synovial plica (symptoms include medial pain, tenderness, and a palpable band along the medial edge of the patella), fat pad inflammation/impingement (inferior pain, tenderness, and swelling deep to the patellar tendon, pain aggravated by knee extension), and patellar tendonitis (inferior pain and tenderness of the inferior pole and patellar tendon).[42] MRI may also be used to grade degrees of chondromalacia or osteochondral defect.[5] Kinematic MRI or computed tomography may also be appropriate, for example, to more accurately define patellar tracking abnormalities, and in these instances the patient is supine or standing upright in a weight-bearing, closed-chain position while performing continuous knee flexion and extension movements.[5][42][43]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer