Aetiology

The differential diagnoses for paediatric abdominal pain are broad and encompass almost every organ system. In addition, distinguishing acute from chronic abdominal pain may be particularly difficult in children. Although the most common aetiologies are not immediately life-threatening, the ability to diagnose urgent pathology remains paramount. A thorough history and physical examination, and an understanding of the more common diseases affecting the child's age group, are essential.

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal (GI) sources are the most common aetiology of abdominal pain in children, encompassing infectious, congenital, functional, and mechanical causes.

Constipation

A common condition, with a reported pooled prevalence of 9.5%.[1]

Childhood constipation is typically characterised by infrequent bowel evacuations, large stools, and difficult or painful defecation.[2][3]

Symptoms usually result from low-fibre, poor-nutrient intake, and too little water, which leads to high levels of colonic reabsorption of water and hardening of the stool. Additional risk factors include genetic predisposition, infection, stress, obesity, low birth weight, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and learning difficulties.

Constipation starts as an acute problem but can progress to faecal impaction and chronic constipation.

It tends to develop during three stages of childhood: weaning (infants), toilet training (toddlers), starting school (older children).

Infantile colic

Characterised by paroxysms of uncontrollable crying in an otherwise healthy and well-fed infant aged <5 months. The duration of crying is >3 hours per day, and >3 days per week, for at least 3 weeks.[4]

The crying typically starts in the first weeks of life and ends by 4-5 months of age.

Food allergy may play a role in the pathogenesis.

Colic occurs equally in both male and female infants.[5] Infants with colic tend to have siblings who also have this condition.

Appendicitis

Develops when the appendiceal lumen becomes obstructed by stool, barium, food, or parasites.

Can occur in all age groups, but is rare in infants. A cohort study in Sweden found that 2.5% of children had had appendicitis by age 18 years.[6]

If left untreated, acute appendicitis may progress to ischaemia, necrosis, and eventually perforation. The overall rate of perforation is about 30%.[7]

Validated paediatric clinical prediction rules may help to quantify risk for appendicitis, but guidelines recommend against making a diagnosis of appendicitis in children based on clinical scores alone.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

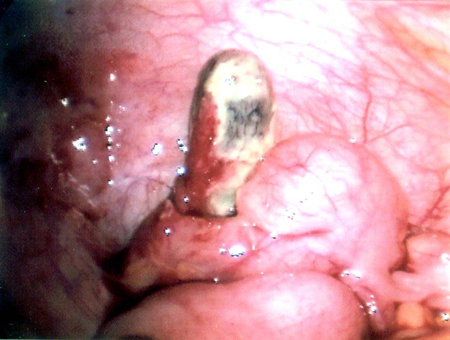

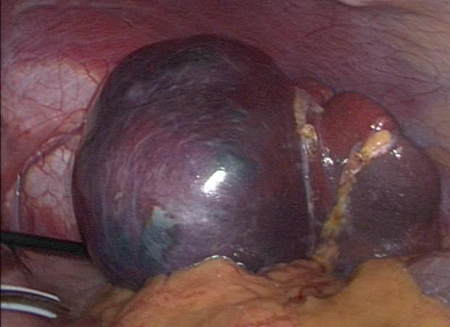

Although the risk of perforation increases if appendectomy is substantially delayed, surgery within 24 hours does not increase the risk of perforation for children with uncomplicated acute appendicitis.[13][14][15][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Necrotic appendixFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

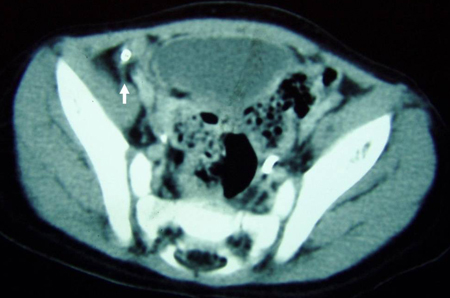

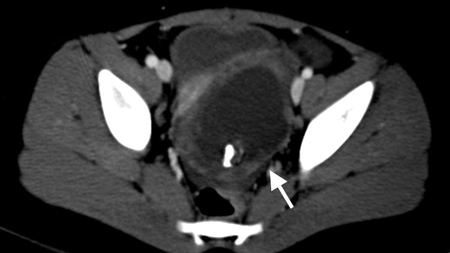

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan demonstrating faecalith (white arrow) outside the lumen of the appendix consistent with perforated appendixFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan demonstrating faecalith (white arrow) outside the lumen of the appendix consistent with perforated appendixFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Stump appendicitis may occur after an appendectomy when the residual stump is >0.5 cm. It can occur after both open and laparoscopic surgery.[16]

Gastroenteritis

May be due to acute or chronic viral infection (especially rotavirus), or bacterial or parasitic infection.

Causes vague, cramping abdominal pain in association with fever, vomiting, and diarrhoea.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis, defined as a condition affecting the GI tract with eosinophil-rich inflammation without a known cause for the eosinophilia, can result in significant abdominal pain.[17]

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome, characterised by microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and nephropathy, can occur as a complication of gastroenteritis caused by verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Abdominal pain is a common presenting symptom.[18]

Intussusception

Occurs when a proximal segment of the intestine telescopes into the lumen of an immediately distal segment. In most cases, the intussusception is in the ileocaecal area.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intussusception: blood vessels become trapped between layers of intestine, leading to reduced blood supply, oedema, strangulation of bowel, and gangrene. Sepsis, shock, and death may eventually occurCreated by the BMJ Knowledge Centre [Citation ends].

Usually occurs in infants between 3 and 12 months of age. Peak incidence is 5-7 months of age.[19]

Intussusception should be suspected in an infant in this age group presenting with colicky abdominal pain, flexing of the legs, fever, lethargy, and vomiting.

In infants <2 years of age, episodes of intussusception are most likely to be caused by mesenteric lymphadenopathy secondary to an associated illness (e.g., viral gastroenteritis). In older children, mesenteric lymphadenopathy is still the most likely cause, but other aetiologies should be considered (e.g., intestinal lymphomas, Meckel's diverticulum). Therefore, children ≥6 years or with jejuno-jejunal or ileo-ileal intussusception should be assessed for a pathological lead point.

Ileo-ileal intussusception may also be indicative of Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP).[20][21] HSP is a vasculitis that affects small veins and primarily occurs in children <11 years of age.[22]

Occasionally, an ultrasound examination will show small-bowel to small-bowel intussusception. If there are no obstructive symptoms, and the wall of the bowel is normal, with length <3.5 cm, and normal vascularity with no colonic involvement, then these findings are usually transient and require no further intervention.[23]

Meckel's diverticulum

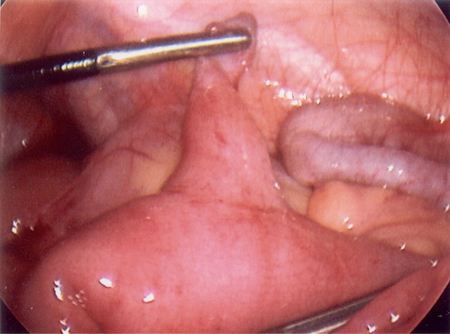

A finger-like projection located in the distal ileum arising from the anti-mesenteric border; usually 40-60 cm from the ileocaecal valve, measuring 1-10 cm long and 2 cm wide. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative photo of Meckel's diverticulumFrom the collection of Dr Kuojen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

The majority of symptomatic patients present before the age of 2 years.

Meckel's diverticulum is a common cause of paediatric gastrointestinal bleeding and should be considered if there is painless rectal bleeding.

The prevalence is estimated to be up to 3%.[24]

Intestinal obstruction is a known complication and may be observed in as many as 40% of all symptomatic Meckel's diverticula (according to some series).[25][26]

Mesenteric adenitis

Refers to inflammation of the mesenteric lymph nodes. This process may be acute or chronic.

It is often mistaken for other diagnoses, such as appendicitis; up to 23% of patients undergoing negative appendectomy have been found to have non-specific mesenteric adenitis.[27]

One retrospective study reported that, compared with children who have appendicitis, patients who have mesenteric adenitis are more likely to have high fever (above 39°C) and dysuria, and are less likely to have migratory pain, vomiting, or typical abdominal signs of appendicitis on examination.[28]

Hirschsprung's disease

Most commonly diagnosed in the first year of life but can present later in childhood; higher male preponderance in the most common anatomical variant (rectosigmoid disease).[29]

Congenital condition characterised by partial or complete colonic obstruction associated with the absence of intramural ganglion cells. Because of the aganglionosis, the lumen is tonically contracted, causing a functional obstruction. The aganglionic portion of the colon is always located distally, but the length of the segment varies. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray of a neonate with abnormal stooling pattern and constipation. The dilated transverse and descending colon is suggestive of Hirschsprung's diseaseFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Hirschprung-associated enterocolitis is the main cause of serious morbidity and death in patients with Hirschprung's disease if not recognised and treated promptly.[30] The classic presenting features include abdominal distention, fever, and diarrhoea; however, other signs or symptoms may include vomiting, rectal bleeding, lethargy, loose stools, and obstipation.[30][31]

May be associated with Down syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIA.

Intestinal obstruction

Small or large bowel obstruction may be the result of various aetiologies and can occur at any age. Abdominal pain may not occur until the obstruction has progressed to include extensive abdominal distension or intestinal ischaemia. Intestinal obstruction may mimic intestinal ileus, which usually does not require surgical intervention.

Intestinal obstruction in a child without a history of prior surgery is traditionally considered an indication for surgery.

The aetiology of intestinal obstruction can be congenital or acquired. Congenital causes include atresias or stenosis, which present in the newborn period. Acquired causes include small bowel adhesions, strangulated or incarcerated hernias, and tumours.

Congenital causes:

Duodenal atresia or stenosis may cause complete or partial obstruction of the duodenum as a result of failed re-canalisation during development. This results in either stenosis with incomplete obstruction of the duodenal lumen (allowing some but not all gas and liquid to pass) or an atresia where the duodenum ends blindly causing a true complete obstruction.

Jejuno-ileal atresia or stenosis is a complete or partial obstruction of any part of the jejunum or ileum. Although uncertain, it is believed to result from a vascular accident during development. Jejunal stenosis may still have bowel lumen continuity with a narrowed lumen and thickened muscular layer. There are four types of atretic bowel: type I, an obstructing web or septum with intact bowel wall and mesentery; type II, an atretic cord of remnant bowel with an intact mesentery; type IIIa, a missing atretic segment with a mesenteric defect; type IIIb, atresia with the distal bowel coiled ('apple peel') around a distal mesenteric vessel; and type IV, multiple segmental atresias ('sausage-links').

Hernias may be internal or external and congenital (most commonly in children) or acquired.

Colonic atresia is a rare complete obstruction of any part of the colon, although it usually occurs near the splenic flexure. Like jejuno-ileal atresia, it is thought to occur as a result of a vascular event.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray demonstrating double bubble gas pattern consistent with duodenal atresiaFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Meconium ileus is an important cause of intestinal obstruction in the neonatal period; cystic fibrosis should be suspected as an associated disease. There may be associated pancreatic abnormalities.

Duplication cysts occur most commonly in the small intestine; they may serve as a lead point for volvulus and intussusception and can also result in obstruction. In the presence of duodenal duplication cysts, peptic ulcer disease, haemorrhage, or perforation may result secondary to ectopic gastric mucosa.

Acquired causes:

May occur at any age.

Tumours may be intraluminal or extra-intestinal.

Hernias may be internal or external and congenital or acquired (e.g., prior operation, incisional, traumatic). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infant with right groin bulge consistent with incarcerated inguinal hernia. The lack of overlying skin oedema and erythema does not rule out strangulation of the small intestineFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

A history of previous intra-abdominal surgery or inflammation (such as necrotising enterocolitis) should prompt concern for adhesive small bowel obstruction.

Bowel obstruction without previous surgical or inflammatory history in the paediatric population should raise concern for aetiologies such as a mass or cyst that requires intervention.

Omental cysts, although rare, can present with intestinal obstruction; may be confused with ovarian cysts on ultrasound.

In patients with cystic fibrosis, partial bowel obstruction may sometimes be referred to as distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS, formerly known as meconium ileus-equivalent syndrome). DIOS is not related to meconium. It refers to a distal small bowel obstruction caused by impacted bowel contents that typically occurs in adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis.

Volvulus

This can occur in any age group but is most common in children <1 year old; at least 60% of children present before 1 month of age.[32] Mid-gut volvulus is the most common type.

Green (bilious) vomiting is a cardinal symptom of duodenal obstruction secondary to mid-gut volvulus.[32]

Intestinal malrotation is a term used to encompass the entire spectrum of anatomical arrangements that result from incomplete rotation of the gut during embryonic development. Volvulus of the entire small bowel and part of the colon is only possible, unless in extremely preterm infants, when malrotation exists.[33]

In malrotation, the most significant pathological concerns are a lack of gut fixation to the retroperitoneum and narrow mid-gut mesenteric base that predisposes patients to mid-gut volvulus, which occurs when the duodenum or colon twist around this mesenteric base.

Colonic volvulus (sigmoid or caecal) is rare.[34] It usually occurs in children with a history of chronic constipation, in dysmotility disorders, or in patients who have cognitive deficits with limited mobility.

Necrotising enterocolitis

A disease primarily of premature infants, particularly those weighing less than 1500 g.[35] The pathogenesis is multifactorial and not well understood, although ischaemia, reperfusion injury, microbiome changes, and infectious pathogens may play a role.

Typical symptoms are feeding intolerance, abdominal distension, and bloody diarrhoea at approximately 1-2 weeks of age.[36] Other signs and symptoms include apnoea, lethargy, abdominal tenderness, abdominal wall erythema, and bradycardia.

Peptic ulcer disease

Gastric and duodenal ulcers are uncommon among the paediatric population.[37] When they occur, they are classified as primary or secondary peptic ulcers.

Primary ulcers occur without predisposing factors and are most commonly located in the duodenum or pyloric channel. They manifest most often in older children and adolescents with a positive family history. Rarely, primary peptic ulcers can occur in the first month of life, presenting with bleeding and possible perforation. Most are located in the stomach. Primary ulcers may be associated with Helicobacter pylori.

Secondary ulcers are usually associated with stress, burns, trauma, infection, neonatal hypoxia, chronic illness, and ulcerogenic medications or lifestyle habits (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], salicylates, corticosteroids, smoking, or intake of caffeine, nicotine, or alcohol).[37] It is important to treat the predisposing condition. Exacerbations and remissions can last for weeks to months.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

This category includes ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, and indeterminate colitis (up to 30% of paediatric cases of IBD in retrospective cohorts, but initial diagnosis may be reclassified during follow-up).[38][39]

Ulcerative colitis affects the rectum and extends proximally; it is characterised by diffuse inflammation of the colonic mucosa and a relapsing, remitting course. Ulcerative colitis is uncommon in children, but prevalence is increasing.[40]

Crohn's disease may involve any or all parts of the entire GI tract from mouth to perianal area. Unlike ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease is characterised by skip lesions. The transmural inflammation often leads to fibrosis, causing intestinal obstruction. The inflammation can also result in sinus tracts that burrow through and penetrate the serosa, giving rise to perforations and fistulas. Onset of Crohn's disease typically occurs in the second to fourth decade of life.[41][42][43]

Ulcerative colitis often presents with bloody diarrhoea, whereas this is an unusual presentation in Crohn's disease. Both conditions cause cramping abdominal pain, anorexia, and weight loss when they present late in the course of the disease. Depending on the intestinal location of Crohn's disease, it may mimic other disease processes such as acute appendicitis.

IBD in the paediatric population can start with very subtle signs that are difficult to interpret. IBD should be considered for any vague, ongoing chronic abdominal pain combined with a slowing of the patient's normal growth curve.

Coeliac disease

Systemic autoimmune disease triggered by dietary gluten peptides found in wheat, rye, barley, and related grains.

Immune activation in the small intestine leads to villous atrophy, hypertrophy of the intestinal crypts, and increased numbers of lymphocytes in the epithelium and lamina propria. Locally these changes lead to GI symptoms and malabsorption.

Coeliac disease is a common disorder in the US and in Europe. A relatively uniform prevalence has been found in many countries, with pooled global seroprevalence and biopsy-confirmed prevalence of 1.4% and 0.7%, respectively.[44]

Patients may present with recurrent abdominal pain, cramping, or distension.[45] Other common symptoms include bloating, weight loss, vomiting and diarrhoea.[46] Dermatitis herpetiformis, an intensely pruritic papulovesicular rash that affects the extensor limb surfaces, almost universally occurs in association with coeliac disease.[46]

Cholelithiasis/cholecystitis

Cholelithiasis describes the entity of stones in the gallbladder (usually asymptomatic or an incidental finding). Biliary colic refers to the classic description of intermittent, recurrent right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain that resolves without intervention. This is usually caused by intermittent obstruction of the cystic duct due to cholelithiasis and contraction of a distended gallbladder.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gallbladder ultrasound demonstrating cholelithiasis with characteristic shadowingFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray with opacities in the RUQ consistent with gallstonesFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray with opacities in the RUQ consistent with gallstonesFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Cholecystitis refers to inflammation of the gallbladder precipitated by obstruction of bile through the cystic duct. Symptoms do not usually resolve spontaneously, and there are specific findings on diagnostic imaging. Cholecystitis may be acalculous (without stones) or calculous (with stones). Choledocholithiasis is the term describing a gallstone(s) in the common bile duct.

Biliary dyskinesia

Characterised by symptoms of biliary colic (intermittent, recurrent RUQ pain that resolves without intervention) in the absence of documented stones in the gallbladder; the diagnosis should be considered in those with symptoms suggestive of biliary colic but with negative laboratory tests and ultrasound in their work-up for symptomatic cholelithiasis.

Caused by abnormal or altered contraction of the gallbladder resulting in biliary colic. Patients have frequently gone through a comprehensive work-up prior to being diagnosed with this entity; increasing recognition and testing for the disease has led to more frequent diagnosis in children.[47]

Viral hepatitis

The viral hepatitides include A, B, C, D, and E.

Hepatitis A virus remains a significant cause of acute viral hepatitis and jaundice, particularly in developing countries, in travellers to those countries, and in sporadic food-borne outbreaks in developed countries.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) frequently causes acute hepatitis and is the most common cause of chronic hepatitis in Africa and the Far East.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) represents the leading cause of chronic viral hepatitis in developed countries.

Hepatitis D virus is a defective virus that needs the presence of hepatitis B to cause clinically recognisable disease.

Hepatitis E virus represents a major cause of mortality in developing countries, especially among pregnant females.

Acute pancreatitis

Refers to inflammation of the pancreas; it does not necessarily imply that infection is present.

Paediatric acute pancreatitis is classified into mild, moderately severe and severe.[48]

Pancreatitis in children is often due to drugs, infection, anatomical abnormalities, or trauma.[49] Corticosteroids, adrenocorticotrophic hormones, oestrogens including contraceptives, azathioprine, asparaginase, tetracycline, chlorothiazides, and valproic acid may induce pancreatitis. Congenital causes include choledochal cyst causing abnormal pancreas and bile drainage and pancreas divisum. Infectious causes include mumps and infectious mononucleosis.

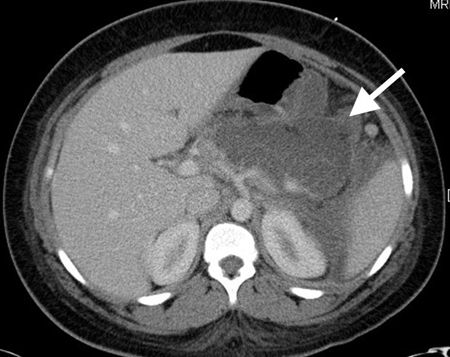

Excessive alcohol and gallstones are the most common causes of pancreatitis in adults; these causes are relatively less common in children, although they may still occur. Paediatric pancreatitis is rare, but the growing population of children with gallstones is likely to increase future incidence. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of teenage girl presenting with mid-epigastric abdominal pain as a result of gallstone pancreatitis. The large fluid collection in the pancreatic bed (white arrow) and lack of pancreatic enhancement suggest liquefactive necrosis of the pancreasFrom the collection of Dr Kuojen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Splenic infarction and cysts

Cysts are classified as either primary or secondary (acquired). Primary cysts are usually congenital and have a true epithelial lining. Eighty percent of splenic cysts are pseudocysts related to infection, infarction, or trauma.[50] Most cysts are incidental diagnoses, although some patients may present with dull, left-sided abdominal pain. In paediatric patients, the most common splenic masses are congenital and/or acquired cysts.[51][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan demonstrating fluid-filled cyst within the spleenFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative photo of large splenic cystFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative photo of large splenic cystFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Splenic infarction occurs when there is occlusion of the splenic blood supply. It may affect the whole organ or only a portion of the spleen, depending on the blood vessels involved. The incidence of splenic infarction is difficult to assess.

Abdominal trauma

A multi-centre prospective study found that abdominal trauma accounted for 3% of admissions to paediatric trauma units.[52]

Generally classified as penetrating or blunt.

Occult blunt abdominal trauma should always be considered in the setting of vague or inconsistent history. The liver, spleen, and kidneys are the most commonly injured intra-abdominal organs in blunt trauma. Most cases of blunt injury to the liver and spleen are managed non-operatively.

It is important to exclude duodenal and/or pancreatic injuries with bicycle handlebar injuries and/or direct blows to the abdomen. Hollow viscus injuries (e.g., stomach and intestines) are more common with penetrating trauma.

It is essential to consider child abuse/non-accidental trauma in this patient population.

Genitourinary

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Infection may arise along any part of the urinary tract including the urethra, bladder, ureter, and kidney. Diagnosis and treatment is paramount to prevent potential long-term adverse effects, including renal or urinary tract scarring and hypertension.

Estimates of the true incidence of UTI depend on rates of diagnosis and investigation. UTI is more common in girls. UTIs affect approximately 4% and 10% of children by ages 1 year and 6 years, respectively.[53]

Bacterial infections are the most common cause, particularly Escherichia coli infection.

Primary dysmenorrhoea

Dysmenorrhoea, or painful menstruation, is one of the most common gynaecological conditions affecting females of reproductive age.[54]

Primary dysmenorrhoea is characterised by menstrual pain in the absence of pelvic pathology.

Nephrolithiasis

Refers to stones that may be located anywhere in the genitourinary tract; the majority of stones are noted in the kidneys, followed by the bladder and ureter.

Most patients have a predisposing factor, such as a family history of nephrolithiasis, high-risk diet (e.g., high oxalate intake), or chronic disease (e.g., renal tubular acidosis).

Stones less than 5 mm in diameter will generally pass spontaneously.

Testicular torsion

A urological emergency caused by the twisting of the testicle on the spermatic cord, leading to constriction of the vascular supply and time-sensitive ischaemia and/or necrosis of testicular tissue.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Young boy with right testicular pain. The testicle is swollen, tender, and erythematous as a result of torsion of the appendix testes. The clinical signs and symptoms mimic those of testicular torsionFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infant boy with swollen, tender, and erythematous left testicle. The testicle is retracted consistent with testicular torsionFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infant boy with swollen, tender, and erythematous left testicle. The testicle is retracted consistent with testicular torsionFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Torsion of an appendix testis resulting in acute infarctionFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Torsion of an appendix testis resulting in acute infarctionFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Has a bimodal distribution, with extravaginal testicular torsion affecting neonates in the perinatal period, and intravaginal testicular torsion affecting males of any age but most commonly adolescent boys.[55]

Systemic symptoms such as nausea and vomiting are not usually present. The thin skin of the scrotum sometimes allows visualisation of the torsed appendage ('blue dot or black dot sign').

The differential diagnosis includes pain from torsion of a testicular appendage; this may develop more gradually (over days to weeks) and frequently is pinpoint (superior pole of testes).

Epididymitis can also mimic testicular torsion, but it is more gradual in onset with less severe symptoms.

Ruptured ovarian cyst

Ovarian cyst rupture is rare and may occur in conjunction with torsion.

Symptoms usually occur prior to the expected time of ovulation and may mimic ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Pain arises from local peritonitis secondary to haemorrhage.[56][57][58]

Ovarian torsion

Although it can affect females of any age, it most commonly occurs in the early reproductive years.[59]

In children, torsion of the ovary is often associated with the presence of an ovarian tumour, most commonly a teratoma.

Twisting or torsion of the ovary compromises the arterial inflow and venous outflow, producing ischaemia, which, if not relieved promptly, can affect the viability of the ovary.

Oophorectomy is infrequently indicated and most ovaries can be preserved.[60][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative photo of ovarian mass that presented as ovarian torsionFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of a young girl presenting with ovarian torsion. The large pelvic cystic lesion contains calcifications (white arrow) consistent with a teratoma or dermoid cystFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of a young girl presenting with ovarian torsion. The large pelvic cystic lesion contains calcifications (white arrow) consistent with a teratoma or dermoid cystFrom the collection of Dr KuoJen Tsao; used with permission [Citation ends].

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Represents a spectrum of upper genital tract infections that includes any combination of endometritis, salpingitis, pyosalpinx, tubo-ovarian abscess, and pelvic peritonitis; usually caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis and less commonly by normal vaginal flora including streptococci, anaerobes, and enteric gram-negative rods.

Adolescents are at higher risk of developing PID compared with older women.[61] Sexually transmitted infections (chlamydia and gonorrhoea) are a key risk factor.[62]

PID is rare in the absence of sexual activity; PID in a young child should prompt work-up for possible sexual abuse.

Pregnancy complications

Miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy should be a concern in any female of reproductive age presenting with lower abdominal pain, amenorrhoea, and vaginal bleeding.

Miscarriage is an involuntary, spontaneous loss of a pregnancy before 20-24 completed weeks. The gestational threshold for the definition varies between countries: in the US it is usually 20 weeks (but may vary in different states), whereas in the UK, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists defines it as 24 weeks.[63][64] The majority of spontaneous miscarriages occur in the first trimester.[65]

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilised ovum implants and matures outside the uterine endometrial cavity, with the most common sites being the fallopian tube (97%), the ovary (3.2%), and the abdomen (1.3%).[66] Use of oral contraceptives before age 16 years is associated with increased risk of ectopic pregnancy.[67] The classic presentation includes lower abdominal pain, amenorrhoea, and vaginal bleeding. Haemorrhage from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy can be fatal.

Pulmonary

Primary respiratory illnesses such as pneumonia or empyema may present as abdominal pain in the paediatric population.[68] Ileus following a thoracic procedure can lead to abdominal distension, GI symptoms, and discomfort.

Recurrent pneumonia in children is usually the result of a particular susceptibility, such as disorders of immunity and leukocyte function, disorders of ciliary function, anatomical abnormalities, or specific genetic disorders such as cystic fibrosis.[69]

Functional abdominal pain

Functional abdominal pain is also referred to as non-specific abdominal pain; pain is usually chronic or recurrent. Visceral hyperalgesia is the final outcome of sensitising medical and psychosocial events, on a background of genetic predisposition.[70]

Functional abdominal pain disorders are classified according to Rome IV criteria, which describe functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, abdominal migraine, and functional abdominal pain - not otherwise specified.[70][71][72]

Typically affects children between 5 and 14 years of age.

Prevalence estimates vary from 10% to 30% in samples of school students, to 87% in some gastroenterology clinics.[73]

Family history of functional disorder common (irritable bowel syndrome, mental illness, migraine, anxiety).

Clarifying the type of functional disorder is important to determine which treatments are most likely to improve symptoms.

Functional dyspepsia

Defined as one or more of the following bothersome symptoms on at least 4 days per month: postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, or burning not associated with defecation. After appropriate evaluation the symptoms cannot be fully explained by another medical condition.[70]

Irritable bowel syndrome

Three criteria must be fulfilled for 2 months prior to diagnosis:[70]

Abdominal pain at least 4 days per month associated with one or more of:

Related to defecation

Change in stool frequency

Change in stool form.

In children with constipation, the pain does not resolve with resolution of constipation.

After appropriate evaluation the symptoms cannot be fully explained by another medical condition.

Abdominal migraine

All of the following criteria must be fulfilled for at least 6 months prior to diagnosis and on at least two occasions:[70]

Paroxysmal episodes of intense, acute periumbilical, midline, or diffuse abdominal pain lasting at least 1 hour. The abdominal pain must be the most severe and distressing symptom.

Episodes separated by weeks or months.

Pain is incapacitating and interferes with normal activities.

Stereotypical pattern and symptoms in the individual.

Pain associated with 2 or more of:

Anorexia

Nausea

Vomiting

Headache

Photophobia

Pallor.

After appropriate evaluation the symptoms cannot be fully explained by another medical condition.

Functional abdominal pain - not otherwise specified

Three diagnostic criteria must be fulfilled at least four times per month, for 2 months prior to diagnosis:[70]

Episodic or continuous abdominal pain that does not occur solely during physiological events (e.g., eating, menstruation)

Insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, or abdominal migraine diagnosis

After appropriate evaluation the symptoms cannot be fully explained by another medical condition.

Alarm features in children with chronic abdominal pain, which may indicate an organic or motility-related rather than a functional cause, include:[70][74][75]

Family history of inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease, or peptic ulcer disease

Persistent right upper or right lower quadrant pain

Dysphagia

Odynophagia

Persistent vomiting

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Nocturnal diarrhoea

Arthritis

Peri-rectal disease

Involuntary weight loss

Deceleration of linear growth

Delayed puberty

Unexplained fever.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer