Approach

Few conditions mimic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV); therefore, a suggestive history combined with a positive physical examination (i.e., a positive Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre or a positive supine lateral head turn) is usually sufficient for diagnosis. Imaging and other testing are not normally required unless there are additional signs or symptoms that warrant further investigation or are suspicious for a central aetiology.[7][35][36]

Clinical evaluation

The first step is to elucidate whether the perceived dizziness is presyncopal or vertiginous. Patients with BPPV present with vertigo: the sensation that the environment is spinning around relative to oneself or vice versa.[7][37]

Nature of onset: of key importance in BPPV is the sudden onset and intense nature of vertigo; a gradual onset or mild vertigo is more suggestive of a central pathology.[7][37] Precipitating events should be sought. In BPPV, specific types of movements, as opposed to any movement, can precipitate an attack. Looking up or bending down, getting up, turning the head, and rolling over in bed to one side are common precipitants. Sometimes patients are able to identify the direction of head movement that precipitates the episode, and this almost always corresponds with the affected ear.[7]

Duration: the duration of the vertigo is also a key finding. The vertigo of BPPV usually lasts <30 seconds. A large proportion of patients with BPPV may experience nausea; often, they describe an episode as lasting much longer because of the associated symptoms of nausea, imbalance, and lightheadedness that may persist. Care should be taken to specifically differentiate the duration of vertigo from other associated symptoms. The vertigo of other disorders lasts much longer: Meniere's disease lasts for hours; viral labyrinthitis or vestibular neuronitis lasts for days; migraines are variable; and other central disorders can be constant. Moreover, BPPV is classically episodic and recurrent, and a single episode is not usually suggestive of BPPV unless confirmed with the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre (posterior canal BPPV) or supine lateral head roll (lateral canal BPPV).[7] If the first episode of vertigo lasted for hours or days, this suggests a preceding vestibular neuronitis and the patient may have other labyrinthine findings and complaints that will not respond to BPPV treatments alone.

Differentiating conditions: an important part of the history is ruling out other possible mimicking conditions. The patient should be asked about any associated symptoms. The presence of hearing loss, tinnitus (a sensation of sound perceived in an ear but not due to the external environment), and symptoms being triggered by pressure changes suggest another diagnosis.[7][37]

Etiology: vertigo can be the result of either a peripheral (inner ear) or a central (brainstem/cerebellum) disorder. BPPV is a peripheral form of vertigo and should not present with or be diagnosed in the presence of neurological symptoms suggestive of a central disorder. Headaches, visual symptoms (double vision, visual field defects, visual loss), other sensory abnormalities such as paraesthesias or deficits, and motor abnormalities all suggest a central aetiology. One exception is that BPPV can occur with or after a migraine episode. A history of vestibular ototoxic drug use can predispose patients to vestibular disorders and should be excluded. Importantly, because it is so common, at times BPPV may co-exist with other conditions, and the clinician should remain aware of this possibility.[7]

Identification of risk factors

Risk factors of BPPV need to be explored to lend support to the diagnosis and differentiate primary from secondary forms. A past history of BPPV, a recent history of head trauma, viral infection (especially upper respiratory infection), a history of viral labyrinthitis or vestibular neuronitis, migraines, inner ear surgery, and Meniere's disease can all predispose patients to BPPV.[7]

Subtypes

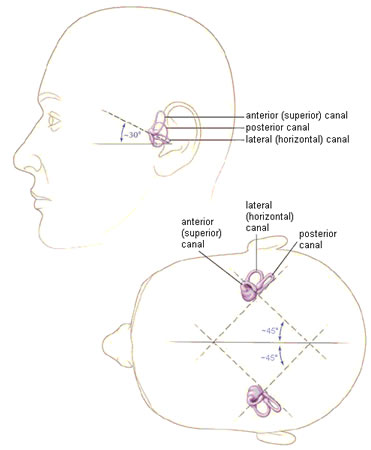

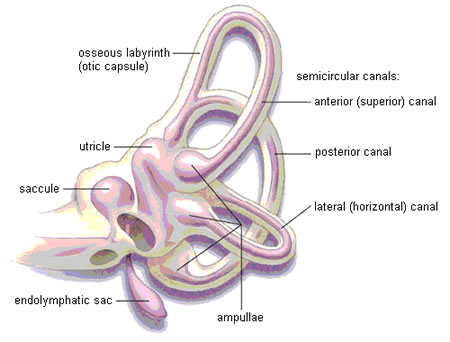

Posterior canal BPPV is by far the most common subtype, followed by lateral (horizontal) and rarely, if ever, superior (anterior) canal BPPV. All subtypes of BPPV present with a similar history, although lateral canal BPPV is usually more intense and the episodes last longer. Patients with lateral canal BPPV often vomit, and the vertigo is not usually provoked by vertical head movements such as looking up, getting up, or bending down, but rather is usually provoked by lateral turning motions such as rolling over in bed.[7][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Spatial orientation of the semicircular canalsParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osseous (grey/white) and membranous (lavender) labyrinth of the left inner earParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osseous (grey/white) and membranous (lavender) labyrinth of the left inner earParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left inner ear. Depiction of canalithiasis of the posterior canal and cupulolithiasis of the lateral canalParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left inner ear. Depiction of canalithiasis of the posterior canal and cupulolithiasis of the lateral canalParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693; used with permission [Citation ends].

General physical examination

A full neuro-otological examination should be conducted, which includes a full cranial nerve examination and cerebellar testing. The use of an otoscope will rule out obvious middle ear disease, and hearing tests (including an audiogram) should be conducted in patients with hearing loss. In BPPV, these tests are almost always unremarkable.[7][37]

Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre

The Dix-Hallpike (also referred to as the Nylen-Barany) manoeuvre is the definitive diagnostic test for posterior canal BPPV. It can also be used to diagnose superior (anterior) canal BPPV, although this is exceedingly rare. The manoeuvre involves the examiner positioning the patient so that the posterior semicircular canal is vertically orientated, and the head moves in the plane of the canal. As a result, canalith particles then gravitate downwards, precipitating an episode of BPPV.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Dix-Hallpike manoeuvreParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003 Sep 30;169(7):681-93; used with permission [Citation ends].

The patient sits on the examination table, their head is turned 45° to one side, and then they are laid back into a supine position, with the head hanging back but supported by the examiner and the neck extended by about 30° (neck extension should be avoided in patients with cervical spondylosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or vascular disease that may limit neck extension or pose a risk for a vascular event). For pure diagnostic testing purposes, the lack of hyperextension should not preclude a positive diagnostic test and, in fact, is preferred by many because the hyperextension may lead to a false-positive test if the condition exists in the contralateral ear. Neck hyperextension is more important during treatment, as the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre is the initial step in some of the repositioning manoeuvres used to treat BPPV. The Dix-Hallpike is positive when the patient experiences vertigo and nystagmus in the head hanging position. In posterior canal BPPV, the nystagmus is mainly torsional (or rotatory), with a weaker vertical component.[7]

In the head hanging position, if the right side is being tested and is affected by BPPV, then the eye will, as viewed by the examiner, rotate in an anticlockwise manner during the fast phase of nystagmus, with a slight up-beating vertical component (towards the forehead). If the left side is being tested and is affected by posterior canal BPPV, then the eye will appear to rotate in a clockwise manner during the fast phase of nystagmus, with a similar slight up-beating vertical component.[7]

In both instances, the nystagmus usually has a latency of 2-5 seconds, a crescendo-decrescendo pattern of intensity, and is transient (typically lasting <30 seconds). Upon resuming a sitting position, the nystagmus reverses. With repeat testing, the nystagmus fatigues and lessens in intensity. Both sides must be tested. Repositioning manoeuvres resolve the vertigo and nystagmus.[7]

In the anterior canal BPPV variant, during the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre, the fast phase of nystagmus would be down-beating in direction (away from the forehead); the torsional component would be similar in direction to that of posterior BPPV of the same ear but the torsional component would be more subtle.[7][38] Using the right side as an example, note that the Dix-Hallpike test with the head turned to the right tests for right posterior canal BPPV and left anterior canal BPPV. A positive response from either canal will induce torsional nystagmus with the top pole of the eye beating towards the ground (counter-clockwise, as viewed by the examiner). But the differentiating finding is that the positive posterior canal response also induces up-beating nystagmus, while a positive anterior canal response also induces down-beating nystagmus. The converse to all of this will hold true when performing the left Dix-Hallpike test.

With all the testing manoeuvres for BPPV, the latency or delay in the onset of nystagmus and vertigo occurs because the particles must overcome the resistance of the endolymph fluid, elasticity of the cupula, and inertia caused by the preceding head movement. The nystagmus is short-lived because the particles reach the limit of descent within 10 seconds. The nystagmus reverses direction when the patient is brought back up from the head hanging to the sitting position because the particles travel in the reverse direction, thereby inducing an endolymph current and cupular displacement in the opposite direction. The fatigability of nystagmus with repeat testing is accounted for by either particle dispersion or central compensation.[7]

Supine lateral head turns

Supine lateral head turns are used to diagnose lateral (horizontal) canal BPPV. Some clinicians recommend performing a supine lateral head turn when the history is suggestive of BPPV but the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre is negative.[35] The clinician places the patient in a supine position and, ideally, flexes the neck 30° from horizontal to bring the lateral canals into the vertical plane of gravity. However, it is sufficient and more usual to simply lay the patient flat on their back. The head is then rotated to one side, left for 1-2 minutes, and then rotated to the opposite side. Similar to the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre, a positive test is noted when the patient experiences vertigo with nystagmus.

Depending on the pathophysiological process, different responses may be observed. The hallmark feature of lateral canal BPPV is pure horizontal nystagmus without a torsional (rotatory) component. In canalithiasis, a head turn towards either side produces a horizontal nystagmus with the fast phase beating towards the ground (geotropic); conversely, in cupulolithiasis the fast phase beats away from the ground (apogeotropic).[7]

In canalithiasis, the side with the stronger response is the affected side, whereas in cupulolithiasis the side with the weaker response is the affected side. In apogeotropic nystagmus of cupulolithiasis, the nystagmus response often persists for longer in the provocative test position.[7][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lateral (horizontal) canal BPPVParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693; used with permission [Citation ends].

In general, the vertigo and nystagmus of lateral canal BPPV has a shorter latency, is less fatigable on repeat testing, can be more severe, and is more often associated with vomiting.[7]

Anterior canal BPPV manoeuvres

The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre can be used to diagnose anterior canal BPPV. Some authors suggest a modification: a straight head hanging manoeuvre that involves the patient moving from a sitting to lying position, with the head tilted (extended) straight back. The fast-phase of nystagmus would be down-beating, and the torsional component (clockwise or counter-clockwise) would suggest the side that is affected similar to posterior canal BPPV of the same ear, although the torsional component is allegedly weaker, and thus more difficult to appreciate on physical examination.[38]

Central nystagmus

During either provocative manoeuvre, central nystagmus is suggested when the nystagmus response is vertical without a torsional component, persists in the provocative position, is not fatigable with repeat testing, and does not reverse directions when going from lying to sitting in the case of posterior canal testing or from one side to the other in the case of lateral canal testing.[7][37]

Special situations

A subset of patients will have subjective BPPV, where the symptoms of vertigo are present without signs of nystagmus. Studies have demonstrated that these patients do just as well with repositioning manoeuvres as those with objective BPPV.[16][39] Therefore, the absence of nystagmus during diagnostic positioning manoeuvres does not preclude a diagnosis of BPPV, especially in the setting of a very suggestive history.[7][37] However, the reported vertigo should follow a pattern similar to expected nystagmus: latency, a transient crescendo-decrescendo nature, and fatigability. Otherwise, there is a greater likelihood of labelling cervical problems or phobic postural vertigo as BPPV.

Simultaneous bilateral BPPV is usually the result of a closed-head injury.[40] This phenomenon is diagnosed when the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre is positive on both sides simultaneously.[7][40]

Indications for management and referral

The diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV can be made by a suggestive history and a positive Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre. The performance of a particle repositioning manoeuvre is the appropriate next step, in order to treat the underlying mechanism of posterior canal BPPV by clearing the debris from the affected posterior semicircular canal. The diagnosis of lateral (horizontal) canal BPPV can be made by a suggestive history and a positive supine lateral head turn. Referral to a tertiary care centre dizziness clinic is indicated in the following situations: suspected lateral (horizontal) canal and the rare superior (anterior) canal BPPV variants; atypical cases (symptoms of hearing loss, tinnitus, pressure sensations or aural fullness, symptoms triggered by ear or intracranial pressure changes, signs of middle ear infection, odd nystagmus profiles during positioning manoeuvres, persistent dizziness or unsteadiness); and cases presenting with other associated neurological symptoms and signs (may require imaging of the posterior fossa).[7]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer