Recommendations

Urgent

Identify acute onset of a unilateral, red, painful, hot, and swollen area of skin, which typically spreads rapidly, as cellulitis.[20][22][23]

The cellulitis may have a well-demarcated or more diffuse border.[20][22][23]

Orange-peel appearance, blistering, superficial bleeding into blisters, petechiae or ecchymoses, and dermal necrosis may also occur.[20][23][24]

Other features may include:

In practice, some patients may report rigors and nausea.

Erysipelas is more superficial than cellulitis, occurs most commonly on the face, and has a well-demarcated border.[20][21][23][26]

In practice, investigate and treat cellulitis and erysipelas similarly.[21]

Think 'Could this be sepsis' based on acute deterioration in a patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[27][28][29]

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis.[27][28][29][30]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis.

Exclude underlying serious conditions that may be associated with cellulitis such as:[21]

Septic arthritis (see our topic Septic arthritis)

Osteomyelitis (see our topic Osteomyelitis).

Urgently (in practice, within 30 minutes of initial clinical assessment) refer for senior review patients with:

Necrotising fasciitis. These patients will usually be managed in the surgical or orthopaedics department. See our topic Necrotising fasciitis

Orbital or peri-orbital cellulitis. These patients will usually be managed by ophthalmology. See our topic Peri-orbital and orbital cellulitis.

Key Recommendations

Cellulitis is an infection of the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue; erysipelas is more superficial, involving only the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics.[20][21] The most common causative bacteria are Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus, but infection can be caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes.[21][23]

Diagnose cellulitis and erysipelas in most cases from history and examination.[22]

Do not routinely obtain:

Blood cultures[20]

Skin swabs[20]

Skin aspirates[20]

Biopsies[20]

Full blood count[23]

Urea and electrolytes[23]

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein.[23]

In patients who are systemically ill and/or have comorbidities, send blood for:

Full blood count[23]

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein[23]

Urea and electrolytes.[31]

Guidelines differ regarding blood, swab, and aspirate cultures in specific circumstances.[20][21][23] In UK practice, general principles are as follows:

Take blood for culture if the patient needs admission, which may be indicated by:

Systemic symptoms and signs, such as hypotension, tachycardia, or pyrexia

Possible unusual organisms (e.g., immersion injury)

Immunocompromising factors

Have a lower threshold for admitting these patients

Take a swab when there is an obvious open wet wound, skin break, or ulcer, or take an aspirate if there is a collection of fluid

Have a lower threshold for taking a swab or aspirate if the patient has diabetes or immunocompromising factors.

If taking samples for culture, aim to take them before giving antibiotics.[32][33][34]

Diagnose cellulitis and erysipelas clinically, mainly from history and examination.[20][23] In practice, investigate and treat cellulitis and erysipelas similarly.[21]

Cellulitis is an infection of the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue; erysipelas is more superficial, involving only the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics.[20][21]

The most common causative bacteria are Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus, but infection can be caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes.[21][23]

Identify cellulitis as an acute-onset, unilateral, red, painful, hot, swollen area of skin that typically spreads rapidly.[20][22][23]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cellulitis of lower leg with open woundMartin Shields, Science Source, Science Photo Library [Citation ends].

The following local skin changes may also be present:

Orange-peel appearance[20]

Also known as ‘peau d’orange’

Caused by superficial oedema around hair follicles, which remain connected to the dermis causing skin dimpling

Blistering/bullae[23]

Superficial bleeding into blisters, or cutaneous haemorrhage, which may present as petechiae or ecchymoses[20][23][24]

Dermal necrosis.[23]

Other aspects may include:

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphangitis (a red line that spreads proximally to the area of cellulitis)

Constitutional features

Systemic manifestations

Practical tip

Unilaterality greatly increases the odds of cellulitis if diagnosis is uncertain in a patient with a red leg. Lack of warmth compared with the unaffected limb can help to exclude cellulitis.

Bear in mind that, although uncommon, bilateral cellulitis may complicate chronic dependent oedema or lymphoedema.[22]

Erysipelas is a distinct form of superficial cellulitis that presents as a well-demarcated, bright-red area of raised skin.[34]

It typically affects the face and lower limbs.[26]

The skin is often fiery red with small vesicles on the surface.[20][34]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Facial erysipelasCDC/Dr Thomas F. Sellers/Emory University [Citation ends].

Practical tip

Think 'Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in a patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[27][28][29] See our topic Sepsis in adults.

The patient may present with non-specific or non-localised symptoms (e.g., acutely unwell with a normal temperature) or there may be severe signs with evidence of multi-organ dysfunction and shock.[27][28][29]

Remember that sepsis represents the severe, life-threatening end of infection.[35]

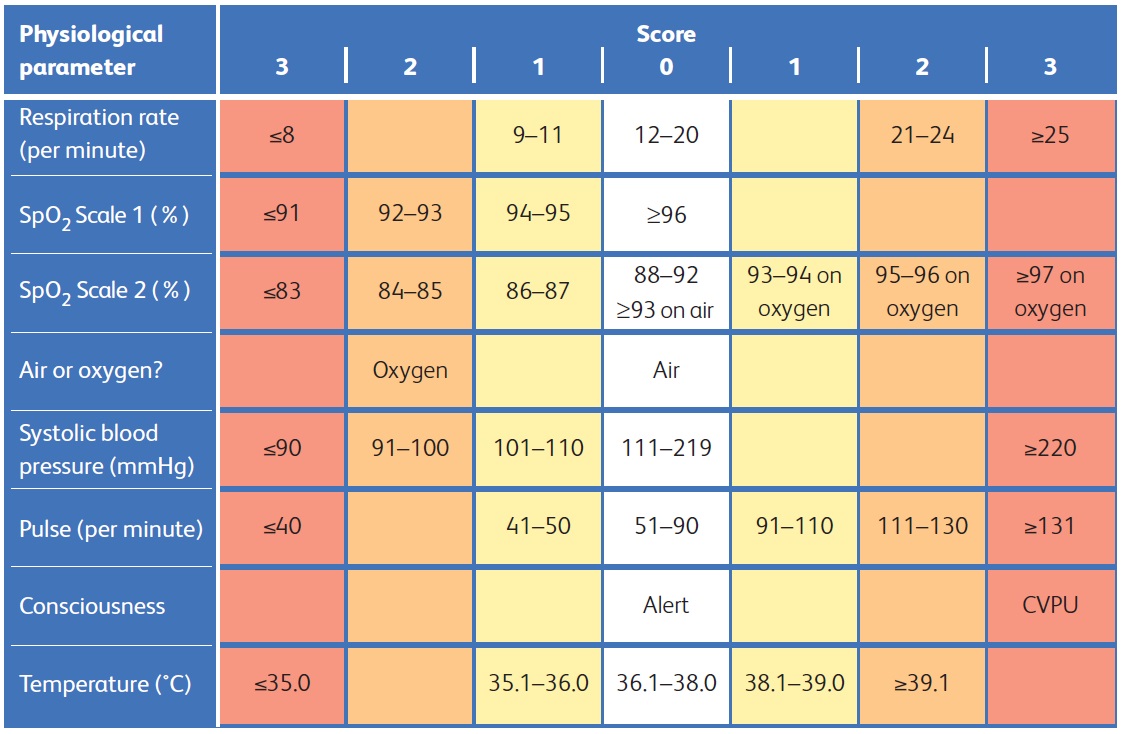

Use a systematic approach (e.g., National Early Warning Score 2 [NEWS2]), alongside your clinical judgement, to assess the risk of deterioration due to sepsis.[28][29][36][37] Consult local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution. Arrange urgent review by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis:[30]

Within 30 minutes for a patient who is critically ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 7 or more, evidence of septic shock, or other significant clinical concerns).

Within 1 hour for a patient who is severely ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 5 or 6).

Follow your local protocol for investigation and treatment of all patients with suspected sepsis, or those at risk. Start treatment promptly. Determine urgency of treatment according to likelihood of infection and severity of illness, or according to your local protocol.[30][37]

Be aware that concurrent osteomyelitis and septic arthritis may occur with cellulitis or erysipelas and require urgent work-up and treatment.[21] See our topics Osteomyelitis and Septic arthritis.

Ask the patient about factors that may indicate:

The source of the infection, including:

Recent cutaneous trauma or surgery[20]

The risk of an atypical organism, such as:

The need for admission. Consider the patient’s:

Potential antimicrobial resistance, such as:

Risk factors

Infections can occur when bacteria breach the skin surface, particularly where there is fragile skin or decreased local host defences.[20]

Screen for the following risk factors:

For information about history and examination of diabetic foot, see our topic Diabetic foot infections

Previous episodes of cellulitis[20]

Examine the skin in the affected area to elicit signs of cellulitis or erysipelas:[23]

Tenderness

Redness

Swelling

Heat.

Note any fluctuance on palpation as this may indicate an underlying abscess.[34]

Note any identifiable portal of entry (e.g., a wound, ulcer, or signs of tinea infection) and local or regional lymphadenopathy.[23]

The following features may indicate more severe cellulitis or erysipelas:[23][31]

Blistering and haemorrhage into blisters

Skin necrosis

Lymphangitis (suggests that the infection is spreading to the lymphatic system).

Examine the patient more generally, noting:

Vital signs; these may indicate severity of the illness:

Temperature

Pulse

Blood pressure

Respiratory rate

Toe-web abnormalities[20]

Risk factors for cellulitis:

See Risk factors in History, above.

Urgent referral

Warning signs include the following.[21]

Sign | Description | Refer to |

|---|---|---|

Lymphangitis | Red lines spreading proximally from the area of infection to lymph nodes via lymphatics. | Senior decision-maker. Local protocols vary and these patients may be admitted under the acute medicine, infectious disease, orthopaedics, or plastics teams, depending on availability and healthcare structure. |

Orbital cellulitis (as it is difficult to differentiate between peri-orbital and orbital cellulitis in practice, refer if in doubt) See our topic Orbital cellulitis | External eye muscle ophthalmoplegia and proptosis.[39] Decreased visual acuity and chemosis.[40] Blurred or double vision.[41] | Ophthalmology. In practice, because this is a sight-threatening condition, refer the patient within 30 minutes of initial clinical assessment. If you are concerned about any delay, seek assistance from a senior clinical decision-maker. |

Necrotising fasciitis See our topic Necrotising fasciitis | Often non-specific signs and similar to cellulitis.[23] Hallmarks include rapid progression and pain out of proportion to clinical signs.[31] Skin inflammation, swelling, discolouration; gangrene and numbness; or pain extending beyond the skin redness.[20] Subcutaneous tissue may feel hard and wooden, and extend beyond the area of apparent skin involvement.[20] A wide red tract may be present, indicating the route of the infection proximally.[20] Crepitus indicates gas in the tissues.[20] Bullous lesions.[20] Skin necrosis or bruising.[20] Often associated with high fever, disorientation, and lethargy.[20] | Surgery or orthopaedics (depending on local policy). In practice, because this is a life-threatening condition, refer the patient within 30 minutes of initial clinical assessment. If you are concerned about any delay, seek assistance from a senior clinical decision-maker. |

Suspected sepsis See our topics Sepsis in adults and Shock | Suspect sepsis based on acute deterioration in a patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[27][28][29] | Ensure urgent review by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK).[28] Consider alerting critical care immediately. |

Examine contiguous joints to exclude septic arthritis.[21]

See our topic Septic arthritis.

Practical tip

You need to exclude osteomyelitis.[21] This can be challenging because osteomyelitis and cellulitis can often overlap. In practice, the pain may not reliably distinguish between the two conditions, and examining deep to an area of cellulitis would be painful for the patient. Have a low threshold for x-ray, and proceed to magnetic resonance imaging if there is any suspicion of a bony infection on x-ray. The x-ray might need to be repeated, as early x-rays may not demonstrate osteomyelitis. See our topic Osteomyelitis.

Assess severity to help guide admission and treatment decisions.[21]

There are several severity assessment systems for cellulitis but none have been shown to be robust for guiding empirical therapy.[31]

In clinical practice, use the Eron classification to guide admission and treatment decisions. In addition, bear in mind the patient’s National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) as an indication of their potential to deteriorate.

The Eron classification suggests four levels of severity.[23][42]

Class I: no signs of systemic toxicity and no uncontrolled comorbidities.

Class II: systemically unwell or systemically well, but with a comorbidity (e.g., peripheral vascular disease, chronic venous insufficiency, or obesity) that may complicate or delay resolution of infection.

Class III: significant systemic signs, such as acute confusion, tachycardia, tachypnoea, or hypotension; unstable comorbidities that may interfere with a response to treatment; or a limb-threatening infection due to vascular compromise.

Class IV: sepsis or a severe life-threatening infection, such as necrotising fasciitis.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) is an early warning score produced by the Royal College of Physicians in the UK. It is based on the assessment of six individual parameters, which are assigned a score of between 0 and 3: respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and level of consciousness. There are different scales for oxygen saturation levels based on a patient’s physiological target (with scale 2 being used for patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure). The score is then aggregated to give a final total score; the higher the score, the higher the risk of clinical deteriorationReproduced from: Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. London: RCP, 2017. [Citation ends].

Clinical findings alone are usually enough for diagnosis.[23]

Do not routinely request laboratory investigations for patients without signs of systemic illness and without any comorbidities.[23]

Bloods

In patients who are systemically ill and/or have comorbidities, send blood for:

Full blood count[23]

Although non-specific, nearly all patients have a raised white blood cell (WBC) count.[23] WBC count may also be low in patients with immunocompromising factors or sepsis

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP)[23]

Urea and electrolytes

Results provide baseline parameters and help assess for end-organ damage as these may influence antibiotic choice; also useful for planning dosing of antimicrobials.[31]

Consider taking liver function tests as they may be helpful parameters for end-organ damage if they are high, and may influence antibiotic choice.[31]

Cultures

Do not routinely culture:[20]

Blood

Yield from blood cultures in cellulitis is very low (2% to 4%) unless infection is severe; contaminants may outnumber pathogens[23]

Skin swabs

Skin aspirates

Biopsies.

If taking samples for culture, aim to take them before giving antibiotics.[32][33][34]

Guidelines differ in nuance regarding blood cultures, swab and aspirate cultures, and biopsy cultures in specific circumstances.[20][21][23] In UK practice, general principles are as follows.

Blood cultures

Take blood for culture if the patient needs admission, which may be indicated by:

Systemic symptoms and signs, such as hypotension, tachycardia, or pyrexia

Possible unusual organisms (e.g., immersion injury)

Immunocompromising factors

Have a lower threshold for admitting these patients.

Swabs and aspirates

Take a swab when there is an obvious open wet wound, skin break, or ulcer, or take an aspirate if there is a collection of fluid. These cultures can be useful in identifying MRSA infection.

Have a lower threshold for taking swabs or aspirates to identify unusual organisms if the patient has:

Diabetes

Immunocompromising factors

Be aware that a fluid collection may develop into an abscess and may require surgery.

The presence of a fluid collection does not always need aspiration; discuss with a senior colleague if you are unsure if diagnostic aspiration is necessary.

Practical tip

Bear in mind that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK specifically recommends that you consider taking a swab for microbiological testing only if the skin is broken and:[21]

There is a penetrating injury, or

There has been exposure to water-borne organisms, or

The infection was acquired outside the UK.

Biopsy

Do not take a simple biopsy just for the purposes of identifying an organism.

Biopsies are rarely performed unless there is an indication for surgery, such as underlying osteomyelitis, or an alternative diagnosis is suspected in a patient with immunocompromising factors or malignancy.

Request histology if you suspect an alternative diagnosis in such cases as it may show infectious or inflammatory features.[20]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Streptococcus pyogenes (Lancefield group A) on Columbia horse blood agarNathan Reading, CC by 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Culture of Staphylococcus aureus on a blood agar plateBMJ Learning, Septic arthritis module [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Culture of Staphylococcus aureus on a blood agar plateBMJ Learning, Septic arthritis module [Citation ends].

Immunocompromising factors

In people with malignancy on chemotherapy, or with neutropenia, severe cell-mediated immunodeficiency, immersion injuries, or immunocompromising factors, consider:[20]

A biopsy or aspirating the lesion for histology and microbiology to exclude differential diagnoses

Molecular diagnostic procedures in immunocompromised patients.

If taking samples for culture and sensitivities, do so before giving antibiotics.[32][33][34]

Suspected abscess underlying cellulitis

In practice, although rare, an abscess may complicate cellulitis if there is a history suggesting a retained foreign body or if there is a fluctuant mass on examination. The fluid collection of an underlying abscess may be visible on ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Necrotising fasciitis

Identify necrotising fasciitis by subcutaneous gas on plain x-ray, ultrasound, or MRI.[25] See our topic Necrotising fasciitis.

In practice, because this is a life-threatening condition, refer the patient within 30 minutes of initial clinical assessment to surgery or orthopaedics (depending on local policy).

If you are concerned about any delay, seek assistance from a senior clinical decision-maker in the accident and emergency department.

Osteomyelitis

Have a low threshold for x-ray, and proceed to MRI if there is any suspicion of a bony infection on x-ray. MRI is the investigation of choice for diagnosing osteomyelitis.

The x-ray might need to be repeated, as early x-rays may not demonstrate osteomyelitis.

See our topic Osteomyelitis.

Practical tip

Excluding osteomyelitis can be challenging because osteomyelitis and cellulitis can often overlap. In practice, the pain may not reliably distinguish between the two conditions, and examining deep to an area of cellulitis would be painful for the patient.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer