Approach

History

Important points to be noted on history include:[1][49]

Rate and degree of regularity of palpitations: sustained, rapid, irregular palpitations may indicate atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, whereas rapid, regular rhythms may indicate paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

Nature of palpitations: feeling of flip-flopping in the chest, often described as the heart stopping and then starting again, or as a skipped beat with the sensation of a pounding beat, a ‘clunk’ or a ‘thud’, usually indicates premature ventricular contractions or premature atrial contractions. A feeling of rapid fluttering in the chest may indicate atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, including sinus tachycardia. Patients often use terms such as 'mechanical' or 'shifting into gear', which are highly suggestive of atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia or atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia. Symptoms that terminate abruptly, especially with a Valsalva manoeuvre, suggest a re-entrant mechanism in which the atrioventricular node is involved (such as atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia or atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia). Symptoms that 'just seem to fade away' are often due to sinus tachycardia

A feeling of rapid and regular pounding in the neck: typical of re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmias, particularly atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia. The sensation is due to atrioventricular dissociation producing contraction of the atria against closed tricuspid and mitral valves. Atrioventricular dissociation can also result from isolated premature ventricular contractions or sustained ventricular tachycardias (VTs)

Palpitations that follow feelings of panic: suggest a diagnosis of panic disorder, although it is often difficult for patients to distinguish whether the feeling of anxiety or panic precedes or follows the palpitations. Certain psychiatric disorders such as panic attack or anxiety disorder are common causes of palpitations, but these diagnoses should not be accepted as sole aetiologies of palpitations until true arrhythmic causes have been excluded[11][12]

Palpitations brought on by exercise (catecholamine excess): suggests an idiopathic VT, particularly those arising from the right ventricular outflow tract.[50] Long QT syndrome can also present with palpitations triggered by vigorous exercise.[2] SVT, particularly atrial fibrillation, may be induced during exercise or at the termination of exercise when the withdrawal of catecholamines is coupled with a surge in vagal tone. This is more common in athletic men in the third to the sixth decade of life.[51][52][53] Palpitations during minimal exertion or emotional stress can also indicate inappropriate sinus tachycardia. This arrhythmia is characterised by inappropriate increases in sinus rates. It is most frequently seen in young women and may result from a hypersensitivity to beta-adrenergic stimulation

Palpitations on awakening (typically early in the morning): there is a well-described association between atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnoea, likely due to large variations in sympathetic and vagal tone at the time of the apnoeic episode. The co-existence of these two conditions should be considered in patients with risk factors for sleep apnoea who awake from sleep with palpitations[54]

Precipitation by emotional stress: most frequently due to anxiety, but may also suggest long QT syndrome with polymorphic VT[55]

Association with position: patients with atrioventricular nodal tachycardia often develop the arrhythmia when they bend over. Some patients note a pounding sensation while lying in bed, particularly when in the supine or left lateral decubitus position. This symptom may be the result of premature beats, which occur more frequently at slow heart rates, and is believed to be due to the sensation of the left ventricle against the thoracic wall

Polyuria: SVT often results in atrial distension and release of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), precipitating a significant diuresis[56][57]

Dizziness, presyncope, or syncope: should prompt a search for VT. Occasionally, syncope occurs with SVT, particularly at the beginning of the tachycardia[1]

Patients with a history of ischaemic heart disease or other structural heart disease are at increased risk of sudden cardiac death, and complaints of palpitations may be due to premature ventricular contractions and/or non-sustained VT. The aetiology of palpitations should be aggressively sought, as well as risk stratification for sudden cardiac death and treatment with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator if indicated

Patients with a history of congenital heart disease (repaired or unrepaired) are prone to multiple types of arrhythmias. Those with chronic volume overload are prone to atrial enlargement leading to atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and atrial tachycardia. Patients with repaired ventricular septal defects or tetralogy of Fallot are prone to re-entrant VT around the ventricular septal defect patch, or from the site of pulmonic valve repair in the right ventricular infundibulum in the case of repaired tetralogy of Fallot

Family history of arrhythmia, syncope, or sudden death from cardiac causes: suggests cardiomyopathy or channelopathy such as long QT syndrome

History suggestive of hyperthyroidism, such as weight loss, heat intolerance, increased frequency of bowel movements

Alcohol use: a significant risk factor for atrial fibrillation[13][43]

Excessive caffeine use

Medication history: stimulants or stimulant-containing medications such as diet pills, or other medications that prolong the QT interval and lead to polymorphic VT (torsades de pointes) such as macrolide and fluoroquinolone antibiotics, and antipsychotic and antidepressant medications.[44] Drugs containing omega-3-acid ethyl esters increase the risk of atrial fibrillation in patients treated for hypertriglyceridaemia.[45][46][47]

Physical examination

Although physicians rarely have the opportunity to examine a patient during an episode of palpitations, the physical examination is useful to define potential cardiovascular abnormalities. Important points on examination include:

General examination: pallor, fever, signs of hyperthyroidism such as warm and sweaty skin, thinning hair and skin, exophthalmos, eyelid lag, pretibial myxoedema

Heart rate and rhythm

Blood pressure

Jugular venous pulse: cannon A waves, seen as a bulging in the neck (sometimes termed a frog sign; occurs when the atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid or mitral valve) as in atrioventricular dissociation[58][59]

Cardiac examination: a laterally displaced and diffuse point of maximal impulse indicates dilated cardiomyopathy. Auscultation may reveal the mid-systolic click of mitral valve prolapse.[33][34] A harsh holosystolic murmur heard along the left sternal border that increases with Valsalva's manoeuvre indicates hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. There may be signs of congestive heart failure such as an S3. Mitral stenosis and regurgitation both lead to left atrial enlargement, which is associated with atrial fibrillation

12-lead ECG

The initial evaluation of all patients with a history of palpitations should include a 12-lead ECG, which can be diagnostic if an arrhythmia correlating with palpitations is recorded. 12-lead ECG also helps to narrow the differential diagnosis in patients with normal sinus rhythm.[1]

Important points to note on ECG include:

Bradycardia: any bradycardia can be accompanied by premature ventricular contractions and palpitations. In particular, complete heart block can be associated with premature ventricular contractions, prolonged QT intervals, and torsades de pointes

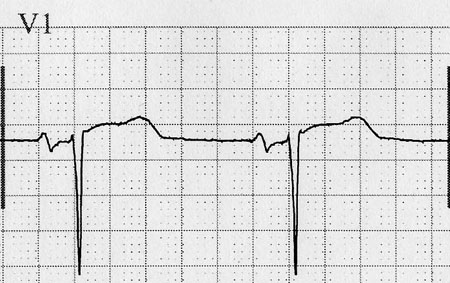

Short PR interval and delta waves: characteristic of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Wolff-Parkinson-White syndromeFrom the collection of Dr C. Pickett [Citation ends].

Prolonged QT interval and abnormal T-wave morphology: suggest long QT syndrome[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Long QT syndromeFrom the collection of Dr C. Pickett [Citation ends].

Deep septal Q waves in I, aVL, and V4 through V6: suggest marked left ventricular hypertrophy due to hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathyFrom the collection of Dr C. Pickett [Citation ends].

Terminal P-wave force in V1 more negative than 0.04 mV and notched in lead II: indicates left ventricular hypertrophy with left atrial abnormality, which may predispose to atrial fibrillation[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left ventricular hypertrophy and left atrial abnormalityFrom the collection of Dr C. Pickett [Citation ends].

Q waves: characteristic of a prior myocardial infarction and warrants a search for sustained or non-sustained VT, as well as atrial fibrillation or flutter[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Inferior Q waves due to prior MIFrom the collection of Dr C. Pickett [Citation ends].

Morphology of ventricular ectopic beats: can help to distinguish between two types of idiopathic VT. Premature ventricular contractions that have left bundle branch block inferior axis morphology might be seen in right ventricular outflow tract VT, whereas idiopathic left ventricular VT will have premature ventricular contractions with right bundle branch block morphology

Epsilon wave or localised QRS prolongation of >110 ms in V1 through V3: suggests arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, as well as findings suggesting right ventricular dilatation such as precordial T-wave inversion[31]

Brugada syndrome patterns: type 1 is diagnostic with ST elevations of >2.0 mm in two of the right precordial leads V1 to V3, with an upward convexity leading down to an inverted T wave, known as a coved pattern.[2] Type 2 and 3 patterns are suggestive but not diagnostic.[2] They are characterised by a saddle-back pattern where the ST elevation descends towards the baseline, then rises up again to an upright or biphasic T wave. The ST segment is elevated >1 mm in type 2 and <1 mm in type 3[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Brugada syndrome ECGFrom the collection of Dr C. Pickett [Citation ends].

Pseudo-S waves in atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia with pseudo-S wavesFrom the collection of Dr C. Pickett [Citation ends].

Further diagnostic testing

Further diagnostic testing should be performed for four groups of people:[1][60][61][62]

When the initial diagnostic evaluation (history, physical examination, and ECG) suggests an arrhythmic cause, especially if the palpitations are associated with syncope.

Those who are at high risk for an arrhythmia without a clear diagnosis after the initial evaluation. This includes people with structural heart disease or myocardial abnormalities including scar formation from myocardial infarction, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, clinically significant valvular regurgitant or stenotic lesions or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; these conditions can lead to serious arrhythmias, especially VT. Other high-risk patients include those with a family history of arrhythmia, syncope, or sudden death from cardiac causes (e.g., cardiomyopathy or the long QT syndrome).

Those patients with factors associated with a high-risk of thrombotic complications from atrial fibrillation in whom, if the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation is established, require anti-thrombotic therapy.

Low-risk patients who are anxious to have a specific explanation for their symptoms.

Modes of further testing include ambulatory monitoring, implantable event monitors, laboratory tests, imaging and electrophysiology studies.

Ambulatory monitoring

Ambulatory monitoring is the definitive means for diagnosing cardiac arrhythmias as the aetiology of a patient's palpitations as it demonstrates the patient's cardiac rhythm during the symptoms. Low-risk patients should have ambulatory monitoring only if the history suggests a sustained arrhythmia that is significantly bothersome to the patient. Even if the patient is low risk and the history is suggestive of premature atrial contractions or premature ventricular contractions, it is sometimes necessary to document this in order to reassure the patient that the palpitations have a benign cause. This can be highly therapeutic in the patient who is excessively concerned about their risk of dangerous arrhythmia.[1] Several types of monitoring systems are available:[63]

Holter monitors: 24-hour monitoring systems that record and save data continuously. They are worn for 1 to 2 days while the patient keeps a diary recording the time and characteristics of symptoms. They are only effective for patients who have daily episodes.

Event monitors or continuous-loop recorders: continuously record data but save the data only when manually activated by the patient during an episode of palpitations. Some models will also automatically record any episodes of arrhythmia, whether symptomatic or not. Although Holter monitors remain popular in clinical practice, continuous-loop recorders are generally more cost effective and effective for the evaluation of intermittent palpitations.[64][65] They can be used for longer periods than Holter monitors and are more likely to record data during palpitations, as most patients with palpitations are not symptomatic every day. A monitoring period of 2 weeks is sufficient to make a diagnosis in many patients.[66]

Mobile continuous outpatient telemetry: offers continuous ECG monitoring and recognises arrhythmias according to prescribed algorithms. Continuous telemetry offers greater sensitivity by 1) recognising arrhythmias that are asymptomatic, and 2) capturing arrhythmias in patients who are not able to manually activate a loop monitor.[67]

Digital devices: increasingly play a role in the diagnosis of palpitations.[68] Many smart watches can monitor heart rates, and the abrupt acceleration of the pulse in conjunction with symptoms of palpitations suggests an arrhythmia. There are also commercially available devices that can record a single and six channel ECG to evaluate in correlation with symptoms.[69]

Implantable event monitors

Implantable event monitors are used for patients who have infrequent palpitations, such as only a few times a year, but the palpitations are associated with worrisome symptoms such as syncope. In such a patient, it may be necessary to establish a firm diagnosis of one of these rare events. These small monitors are placed in the left prepectoral subcutaneous tissue and will automatically store ECGs of specific events such as extreme tachycardia or bradycardia, or asystole. Any episode that the patient identifies as an episode of palpitation will also be stored. These stored ECGs are then retrieved from the device memory when analysed through the use of telemetry.

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests may also be useful to exclude specific underlying causes:

Thyroid stimulating hormone: for evaluation of sinus tachycardia or atrial fibrillation

FBC: anaemia could be an explanation for sinus tachycardia

Electrolyte profile: electrolyte abnormalities (particularly hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia) often incite and/or contribute to VT

Imaging studies

Imaging studies that can be considered are:

Transthoracic echocardiogram: may be indicated when there is evidence of ischaemic heart disease or structural heart disease is suspected, but is rarely appropriate without other symptoms or signs of heart disease.[70]

This is of fundamental importance when risk stratifying patients for a malignant aetiology to their palpitations.

Cardiac MRI: modality for assessing cardiac structure and function often with even greater fidelity than echo. It has the advantage of being able to specifically characterise cardiac tissue, which is particularly useful in diagnosing conditions such as arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy or cardiac sarcoid. Cardiac scarring, as detected by MRI, is associated with increased risk of arrhythmias. Evaluation with MRI should be reserved for situations in which such a diagnosis is suggested, but not confirmed, by echocardiogram.

Electrophysiology studies

Electrophysiology studies, with or without preceding ambulatory monitoring, should be performed in two situations:

If palpitations are sustained or poorly tolerated and there is evidence of heart disease, particularly with left ventricular ejection fraction <40%. An electrophysiology study can be performed to see whether ventricular arrhythmias are inducible, in which case the patient would be a candidate for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

If an arrhythmia is identified that is treatable with ablation, such as atrial flutter, atrioventricular node re-entry tachycardia, or atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia. An electrophysiology study should be performed as the diagnostic part of a therapeutic ablation procedure.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer