Epidemiology

High-altitude illness (HAI) typically occurs within hours or days of ascending to altitudes above 2000 m.[5] It typically occurs in lowland residents and sometimes in those from high altitude who have spent considerable time at low altitude. The development of acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) depend upon a number of human and environmental risk factors. These include: height reached, rate of ascent, age, awareness of high-altitude illness before travel, location of long-term residence, exertion, underlying medical conditions, and history of previous high-altitude illness.[6]

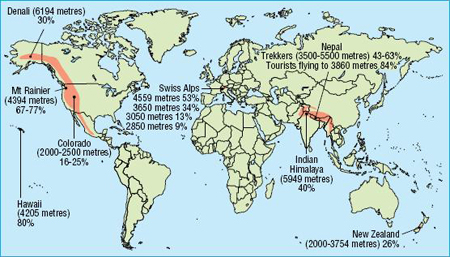

There appears to be little difference in incidence between men and women, or adults and children.[7] The exact incidence is difficult to determine, as the combination of different risk factors and inaccuracies with field diagnosis impact upon the results of epidemiological studies. However, it is clear from a large number of studies that AMS is the most common high-altitude illness.[6] In those staying at alpine huts in Western Europe, the incidence of AMS has been shown to approximate 9% at 2850 m, 13% at 3050 m, and 34% at 3650 m.[8] At higher altitudes in the Himalayas, the incidence of AMS has been shown to range between 10% (3000 to 4000 m), 15% (4000 to 4500 m), and 51% (4500 to 5000 m), depending upon the altitude reached.[9] HAPE is more common than HACE, although both diseases often coincide. HAPE can still occur in up to 3%, and HACE in 1%, of those individuals who ascend slowly to altitudes above 3000 m.[7]

In those ascending more rapidly, the incidence of AMS, HAPE, and HACE increases. In one study, in the Mount Everest region of Nepal, 84% of those who flew directly to nearby Shayangboche (3740 m) complained of symptoms of AMS the following day.[10] Indian soldiers transported to 3600 m were more likely to contract HAPE following a rapid (15.5%) ascent, rather than a much slower (2.3%) ascent profile.[11] Similarly, 31% of Vedic pilgrims at a high-altitude lake in Nepal were diagnosed with HACE following a very rapid 2-day ascent from low altitude to 4300 m.[12]

Between 13% and 20% of those who present with HAPE show signs of HACE, and up to 50% of those who die from HAPE also have evidence of HACE on autopsy.[13][14]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Global incidence of acute mountain sicknessFrom: Barry PW, Pollard AJ. BMJ. 2003;326:915-919 [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer