Aetiology

The primary systemic vasculitides are autoimmune disorders of unknown aetiology. One explanation for their development is that exposure to an unidentified antigen, such as a virus, toxin, or cryptic epitope, leads to activation of the immune response.[6] In some people, this immune response is not down-regulated, leading to production of immune complexes that deposit in blood vessel walls and mainly leading to small vessel vasculitis; it is less clear whether large vessel vasculitis is driven by antibodies. This model leaves many unanswered questions. For example, the anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic auto-antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides are not immune-complex mediated and do not fit neatly into this model. These forms of vasculitis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis) are typically associated with ANCA, which are hypothesised to cause vascular damage indirectly by priming neutrophils to degranulate and to produce oxygen-free radicals. Genetic susceptibility is highly likely in Kawasaki disease, whereas the role of genetic factors is suspected but less clear in other conditions such as Behcet’s syndrome.[4][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT demonstrating cavitary pulmonary lesion secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis, a common form of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic auto-antibody-associated vasculitisFrom the collection of Dr Philip Seo [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

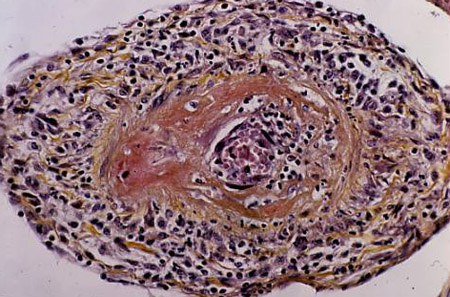

The inciting factor for most forms of vasculitis is not clear. Why specific forms target particular organs is an important but unanswered question. The unifying feature of systemic vasculitis, however, is the presence of immune-mediated blood vessel wall injury. Fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall with karyorrhexis (fragmentation of the nucleus and the break-up of the chromatin into unstructured granules) and red blood cell extravasation are pathognomonic for this disorder.[7] Note that a perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate is not diagnostic of vasculitis and may be seen in other inflammatory conditions. Direct immunofluorescence may reveal the likely aetiology of the vasculitis. Immunoglobulin (Ig) M and C3 deposition are consistent with a mixed-essential cryoglobulinaemia. IgA deposition is seen in IgA vasculitis. The presence of a pauci-immune vasculitis with minimal immunoreactants on immunofluorescence is consistent with an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic auto-antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Biopsy specimen showing florid transmural inflammation of a small arteryFrom the collection of Loic Guillevin, MD, Hopital Cochin, Paris, France [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph of the aorta from a patient with Takayasu's arteritis demonstrating marked thickening of the intimal layer and inflammatory infiltrates in the media and laminar necrosisFrom the collection of Dylan Miller, MD, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph of the aorta from a patient with Takayasu's arteritis demonstrating marked thickening of the intimal layer and inflammatory infiltrates in the media and laminar necrosisFrom the collection of Dylan Miller, MD, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends].

Classification

2012 revised international Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) nomenclature of vasculitides[1]

The CHCC nomenclature system should not be used to specify what findings must be observed in a specific patient to classify that patient for clinical research, nor as a diagnostic system to direct clinical management.

Large-vessel vasculitis affects large arteries (the aorta and its major branches) more often than other vasculitides. The major variants are:

Takayasu's arteritis

Giant cell arteritis.

Medium-vessel vasculitis predominantly affects medium-sized arteries (main visceral arteries and their branches). Inflammatory aneurysms and stenoses are frequent. The major variants are:

Polyarteritis nodosa

Kawasaki's disease.

Small-vessel vasculitis mostly affects small vessels (small intra-parenchymal arteria, arterioles, capillaries, venules), although medium-sized arteries and veins may be affected. Small-vessel vasculitis is subcategorised according to a paucity or a prominence of vessel wall immunoglobulin:

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic auto-antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis

Microscopic polyangiitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Immune complex small-vessel vasculitis

Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

IgA vasculitis

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis.

Variable-vessel vasculitis may affect any size (small, medium, or large) and any type (arteries, veins, or capillaries) of vessel. It includes:

Behçet's disease

Cogan's syndrome.

Single-organ vasculitis affects arteries or veins of any size in a single organ, with no features indicating that it is a limited expression of systemic vasculitis. Vasculitis distribution may be unifocal or multifocal (diffuse) within an organ. Types of single-organ vasculitis include:

Cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis

Cutaneous arteritis

Primary central nervous system vasculitis

Isolated aortitis.

Vasculitis associated with systemic disease includes:

Lupus vasculitis

Rheumatoid vasculitis

Sarcoid vasculitis.

Vasculitis associated with probable aetiology includes:

Hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis

Hepatitis B virus-associated vasculitis

Syphilis-associated aortitis

Drug-associated immune complex vasculitis

Drug-associated ANCA-associated vasculitis

Cancer-associated vasculitis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer