Although patients are often asymptomatic, a clinical diagnosis can be made via the classical auscultatory findings and confirmed with echocardiography. It is common for patients to survive into adulthood even if valvuloplasty is not performed. However, with age the valve may undergo fibrous thickening and, rarely, calcification, which progressively reduces valve motility, leading to increased outlet obstruction and the appearance of symptoms. The risk of progression is highest during infancy.[12]Rowland DG, Hammill WW, Allen HD, et al. Natural course of isolated pulmonary valve stenosis in infants and children utilizing Doppler echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1997 Feb 1;79(3):344-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9036756?tool=bestpractice.com

History and examination

Most patients present with mild to moderate disease and are asymptomatic. A history may reveal the presence of risk factors including black ancestry, or rare causes such as a family history of Noonan syndrome, Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (previously known as LEOPARD syndrome), Alagille's syndrome, Williams' syndrome, maternal rubella exposure during first trimester of pregnancy, rheumatic fever, endocarditis, or carcinoid syndrome. Severe pulmonary stenosis (PS) presents with exertional dyspnoea, fatigue, chest pain, or syncope with exertion. Exertional dyspnoea and fatigue develop due to reduced pulmonary blood flow and right-sided heart failure. Syncope results from reduced pulmonary blood flow, which can decrease cardiac output due to limited pulmonary venous return. It occurs in patients without a right-to-left shunt, inspiring the phrase 'better blue than grey'. Infants with severe or critical disease may present with failure to thrive.

Physical examination findings include:

Prominence of the jugular venous A wave.

Right ventricular (RV) heave noted in the left parasternal and xiphoid region and a systolic thrill noted on palpation along the left upper sternal border; both are signs of severe to critical disease.

A long and harsh systolic ejection murmur with or without a systolic ejection click, usually at the left upper sternal border. Splitting of S2 may also be present. The loudness of murmur is not always related to severity, but the length of murmur, the splitting and intensity of S2, and the timing of ejection click (the earlier, the more stenotic) are related to severity. In severe and critical PS there is usually a long and harsh murmur peaking later in systole. However, in critical PS, the murmur may be soft due to poor cardiac output. The presence of a lower left parasternal systolic murmur suggests associated tricuspid regurgitation. A decrescendo diastolic murmur suggests pulmonary regurgitation.

Signs of right-sided heart failure, which may be seen in severe disease and are always seen in critical disease. These include jugular venous distension, peripheral oedema, ascites, hepatomegaly, and dullness to percussion of the chest (due to a pleural effusion).

Cyanosis, a feature of critical PS produced by right-to-left shunting through an associated septal defect or a patent foramen ovale. It is detected in the lips and fingers.

Rarely, dysmorphic features may be identified, suggesting the presence of a syndrome associated with PS. These include:

Noonan syndrome: features include typical facies of down-slanting or wide-set eyes, low-set or abnormally shaped ears, and sagging eyelids (ptosis); growth retardation; delayed puberty with undescended testicles; pectus excavatum; and a webbed and short-appearing neck. See Noonan syndrome.

Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines: features include growth retardation, lentigines, ocular hypertelorism, abnormal genitalia (usually cryptorchidism or unilateral testis), and retarded growth.

Williams' syndrome: features include microcephaly (30%); typical facies of short upturned nose, flat nasal bridge, long philtrum, flat malar area, wide mouth, full lips, dental malocclusion/widely spaced teeth, micrognathia, stellate irides, and peri-orbital fullness; hypoplastic nails, lax skin; joint hyperelasticity, hallux valgus, contractures, kyphoscoliosis, and lordosis.

Alagille's syndrome: features include growth retardation and typical facies of a broadened forehead, pointed chin, and elongated nose with bulbous tip.

First line investigations

A standard 12-lead ECG is routinely performed to identify cardiac anomalies that may be associated with congenital heart disease or valve disease.[13]Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30121239?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e35-71.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33332149?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]European Society of Cardiology. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease (previously grown-up congenital heart disease). Aug 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Grown-Up-Congenital-Heart-Disease-Management-of

ECG findings are typically normal in patients with mild PS. Right axis deviation is commonly seen in moderate to severe PS.[2]Ruckdeschel E, Kim YY. Pulmonary valve stenosis in the adult patient: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Heart. 2019 Mar;105(5):414-22.

https://www.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312743

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30337335?tool=bestpractice.com

Right bundle branch block is usually seen; the exception is patients with Noonan syndrome, who have left bundle branch block.

Chest x-ray is also routinely performed in patients with known or suspected valve disease or congenital heart disease.[14]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e35-71.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33332149?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]European Society of Cardiology. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease (previously grown-up congenital heart disease). Aug 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Grown-Up-Congenital-Heart-Disease-Management-of

Findings may be normal or show a prominent main pulmonary artery. In severe PS, marked cardiomegaly, right atrial and ventricular enlargement, and decreased pulmonary vascularity may be seen.

The investigation of choice is a two-dimensional echocardiogram with Doppler assessment.[13]Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30121239?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]European Society of Cardiology. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease (previously grown-up congenital heart disease). Aug 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Grown-Up-Congenital-Heart-Disease-Management-of

This enables visualisation of pulmonary valve stenosis, confirming the diagnosis, and classifies the severity by measuring the transvalvular gradient. A transthoracic echocardiogram is usually performed first-line; a transoesophageal echocardiogram may provide complementary information in adult or adolescent patients.[13]Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30121239?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]European Society of Cardiology. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease (previously grown-up congenital heart disease). Aug 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Grown-Up-Congenital-Heart-Disease-Management-of

[16]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria®: congenital or acquired heart disease. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3102389/Narrative

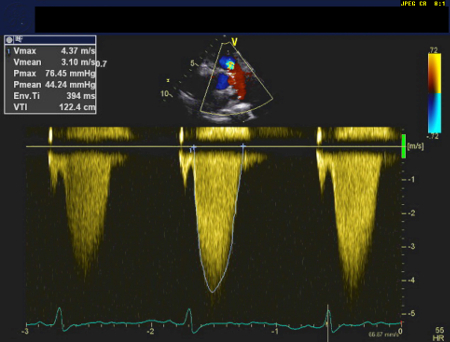

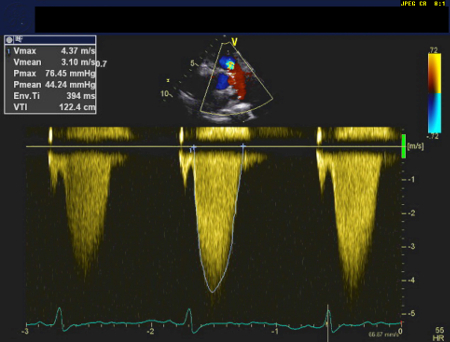

The severity of right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction is classified as follows:[13]Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30121239?tool=bestpractice.com

Mild: peak gradient is <36 mmHg and peak velocity is <3 m/s

Moderate: peak gradient is 36-64 mmHg and peak velocity is 3-4 m/s

Severe: peak gradient is >64 mmHg and peak velocity is >4 m/s; mean gradient is >35 mmHg. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Continuous wave doppler demonstrating severe pulmonary stenosis on transthoracic echocardiogramUsed with permission by National University Heart Centre, Singapore [Citation ends].

Other investigations

Diagnostic cardiac catheterisation may be required in some patients to more precisely confirm the extent, severity, and level of RVOT obstruction.[13]Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30121239?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e35-71.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33332149?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]European Society of Cardiology. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease (previously grown-up congenital heart disease). Aug 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Grown-Up-Congenital-Heart-Disease-Management-of

Critical pulmonary stenosis may occur in neonates if the RVOT obstruction caused by the stenotic valve is so severe that it leads to cyanosis. The major source of pulmonary blood flow in severely obstructed patients is through the ductus arteriosus. Once the ductus arteriosus begins to close, blood flow will be insufficient and the neonate will become hypoxaemic.[9]Latson LA. Critical pulmonary stenosis. J Interv Cardiol. 2001 Jun;14(3):345-50.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12053395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12053395?tool=bestpractice.com

If cyanosis is present, additional investigations that are required include pulse oximetry (revealing low arterial oxygen saturation), a full blood count (reveals an elevated haemoglobin and haematocrit if there is a right-to-left shunt, reflecting erythrocytosis), and arterial blood gases (which reveal low PaO₂).

Imaging modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or cardiac computed tomography are not first-line investigations but can support procedural planning and may be requested by the cardiac interventionist and/or surgeon.[13]Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30121239?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]European Society of Cardiology. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease (previously grown-up congenital heart disease). Aug 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Grown-Up-Congenital-Heart-Disease-Management-of

Exercise stress testing may be used to objectively assess symptoms if considering intervention.[13]Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30121239?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e35-71.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33332149?tool=bestpractice.com