Approach

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is a clinical diagnosis and there is no single diagnostic test for the disease. While the most common presentation is fever and arthritis, careful consideration of all of the manifestations of ARF is required, along with consideration of alternative diagnoses for each manifestation.

Diagnostic criteria for rheumatic fever have evolved since the publication of the original Jones criteria in 1944.[57] In the modern era, diagnostic criteria have evolved to be more sensitive in high-incidence rheumatic fever populations, and to acknowledge the role of echocardiography and a broader spectrum of joint manifestations.

A useful guide to diagnosis can be found within the 2015 update of the Jones criteria, which outlines a diagnostic approach from 4 presenting symptoms/signs: chorea, arthritis, clinical carditis, and subcutaneous nodules/erythema marginatum.[2]

Similarly useful algorithmic approaches are contained within guidelines published in Australia and New Zealand. Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease Opens in new window Heart Foundation of New Zealand: diagnosis, management and secondary prevention of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease Opens in new window

Diagnosis of a primary episode: Jones criteria

The diagnosis of ARF is made on the basis of identification of major and minor clinical manifestations of the disease as detailed by the Jones criteria. The latest revision of the Jones criteria, published in 2015, provides 2 separate sets of criteria: one for low-risk settings (i.e., those with a rheumatic fever incidence ≤2 in 100,000 school-aged children or all-age rheumatic heart disease [RHD] prevalence ≤1 in 1000 population per year) and one for moderate- to high-risk populations.[2]

The diagnosis of a primary episode of ARF can be made if any of the following criteria are met.

Evidence of a recent group A streptococcal infection with at least 2 major manifestations or 1 major plus 2 minor manifestations present.

Rheumatic chorea: can be diagnosed without the presence of other features (which is described as 'lone chorea') and without evidence of preceding streptococcal infection. It can occur up to 6 months after the initial infection.

Chronic RHD: established mitral valve disease or mixed mitral/aortic valve disease, presenting for the first time (in the absence of any symptoms suggestive of ARF).

The 2015 criteria also allow for the diagnosis of possible rheumatic fever. This category of diagnosis allows for the situation when a given clinical presentation may not fulfil the revised Jones criteria but the clinician may still have good reason to suspect the diagnosis.

Major and minor manifestations

Five manifestations are considered major manifestations of ARF:[2]

Carditis: includes carditis demonstrated only by echocardiogram (i.e., subclinical carditis).

Arthritis: polyarthritis (low-risk populations) or monoarthritis or polyarthritis or polyarthralgia (moderate- to high-risk populations).

Chorea.

Erythema marginatum: pink serpiginous rash with a well-defined edge. It begins as a macule and expands with central clearing. The rash may appear and then disappear before the examiner's eyes, leading to the descriptive term of patients having 'smoke rings' beneath the skin.

Subcutaneous nodules.

Four manifestations are considered minor manifestations of ARF:[2]

Fever: ≥38.5°C (≥101.3°F; low-risk populations) or ≥38.0°C (≥100.4°F; moderate- to high-risk populations.

Arthralgia: polyarthralgia (low-risk populations) or monoarthralgia (moderate- to high-risk populations).

Elevated inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥60 mm/hour and/or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥28.57 nanomols/L (≥3.0 mg/dL) (low-risk populations) or ESR ≥30 mm/hour and/or CRP ≥28.57 nanomols/L (≥3.0 mg/dL) (moderate- to high-risk populations).

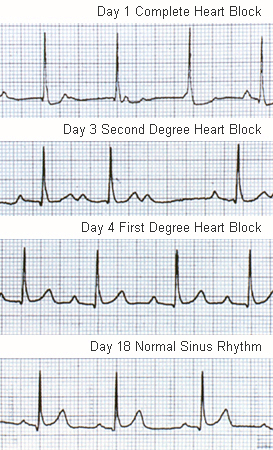

Prolonged PR interval on electrocardiogram after accounting for age variability: a prolonged PR interval that resolves over 2 to 3 weeks may be a useful diagnostic feature in cases when clinical features are not definitive. First-degree heart block sometimes leads to a junctional rhythm. Second-degree and even complete block are less common but can occur. In a resurgence of ARF in the US, 32% of patients had abnormal atrioventricular conduction.

It is important to note that, in a patient in whom arthritis is considered a major manifestation, arthralgia cannot be counted as a minor manifestation. In a patient in whom carditis is considered as a major manifestation, a prolonged PR interval cannot be counted as a minor manifestation. See Criteria.

Carditis: clinical presentation

Rheumatic carditis refers to the active inflammation of the myocardium, endocardium, and pericardium that occurs in rheumatic fever. While myocarditis and pericarditis may occur in rheumatic fever, the predominant manifestation of carditis is involvement of the endocardium presenting as a valvulitis, especially of the mitral and aortic valves. Carditis is diagnosed by the presence of a significant murmur, or the development of cardiac enlargement with unexplained cardiac failure, or the presence of a pericardial rub. In addition, evidence of valvulitis on echocardiogram (using published criteria) is now considered a manifestation of carditis.[2][58]

Mitral regurgitation is the most common clinical manifestation of carditis and can be heard as a pan-systolic murmur loudest at the apex. Cardiac failure occurs in <10% of primary episodes of rheumatic fever.[59][60] Shortness of breath may be related to cardiac failure. Pericarditis is uncommon in ARF, and when it occurs, is usually accompanied by significant valvulitis. Pericarditis should be suspected in patients with chest pain, diminished pulses, a pericardial rub on auscultation, or an enlarged heart on chest x-ray. Individuals with rheumatic carditis may experience palpitations in association with advanced heart block.

Echocardiographic evidence in the absence of clinical findings of carditis (i.e., subclinical carditis) is now considered sufficient as a major manifestation of ARF. There are specific Doppler and morphological findings on echocardiography that must be met.[2]

Recurrent carditis can be difficult to diagnose but is more likely if the first episode of rheumatic fever included carditis and the patient has not been receiving continuous penicillin secondary prophylaxis. It may be suspected by a new murmur, new signs of congestive heart failure, radiographic evidence of cardiac enlargement, or worsening echocardiographic changes.

Joint involvement: clinical presentation

Joint involvement occurs in upwards of 75% of cases of primary rheumatic fever, and may be a major manifestation or a minor manifestation.[60][61] The classic history of joint involvement in ARF is one of large joint migratory polyarthritis, which may be either migratory or additive. If the patient has monoarthritis and is suspected to have ARF, but does not meet the criteria for diagnosis, the patient should withhold from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment so that the appearance of migratory polyarthritis (a major manifestation) is not masked. The arthritis of ARF is very sensitive to salicylates such as aspirin (as well as other NSAIDs), and joint symptoms typically respond within several days of treatment with these anti-inflammatory drugs in ARF.

Chorea: clinical presentation

In 5% to 10% of patients, chorea features as part of the acute presentation.[60][62] It may also occur as an isolated finding up to 6 months after the initial group A streptococcal infection. It is also known as Sydenham chorea (named after the physician who described St. Vitus Dance in the 17th century).

The history may be of a child who becomes fidgety at school, followed by apparent clumsiness along with uncoordinated and erratic movements, often with an associated history of emotional lability and other personality changes. Choreiform movements can affect the whole body, or just one side of the body (hemi-chorea). The head is often involved with erratic movements of the face that resemble grimaces, grins, and frowns; and the tongue, if affected, can resemble a 'bag of worms' when protruded, and protrusion cannot be maintained. In severe cases of chorea, this may impair the ability to eat, write, or walk, placing the person at risk of injury. Chorea disappears with sleep and is made more pronounced by purposeful movements. Typically, when asked to grip the physician's hand, the patient will be unable to maintain grip and rhythmical squeezing results. This is known as the milkmaid's sign. Other signs of chorea include spooning (flexion at the wrist with finger extension when the hand is extended) and the pronator sign (when the palms turn outwards when held above the head). Recurrence and fluctuations of rheumatic chorea are not uncommon, often associated with pregnancy, intercurrent illness, or the oral contraceptive pill.

Investigations

The diagnosis of rheumatic fever requires a series of investigations. The minimum set of investigations required for suspected ARF is:[63]

ESR, CRP, and white blood cell count: Australian data found that CRP and ESR were commonly elevated in patients with confirmed ARF (excluding chorea), whereas the leukocyte count usually was not elevated.[64] Therefore the authors do not recommend including white cell count in the diagnosis of rheumatic fever.

Blood cultures if febrile: helps to exclude other infectious causes, particularly bone and joint infection and infective endocarditis.

Electrocardiogram: to look for lengthening of the PR interval.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing heart block in acute rheumatic feverAust N Z J Med. 1996 Apr;26(2):241-2; used with permission [Citation ends].

Chest x-ray if clinical or echocardiographic evidence of carditis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray of biventricular heart failure due to acute carditis in rheumatic feverLancet. 2006 Jun 24;367(9528):2118; used with permission [Citation ends].

Echocardiogram: to look for evidence of acute carditis and/or RHD. The role of echocardiography in the diagnosis of ARF was once controversial;[65][66] however, it is now accepted that echocardiography is more sensitive and specific than cardiac auscultation for the identification of rheumatic valvular disease.[67][68] It is recommended that all patients with suspected ARF, with or without clinical evidence of carditis, should have an echocardiogram. If initially negative, it may be repeated after 2-4 weeks as carditis can evolve over several weeks and its presence or absence may have major implications for diagnosis and ongoing management. There are published morphological and Doppler findings that are typical of rheumatic fever (see below).[2] In addition, echocardiography is useful in grading severity of rheumatic carditis and differentiating congenital from acquired valvular pathology, and can be used to investigate suspected valve damage.

Throat culture: culture for group A Streptococcus (preferably prior to starting antibiotic therapy). Less than 10% of the throat cultures are positive for group A streptococci, reflecting the post-infectious nature of the disease.[69] Group A streptococci have usually been eradicated before onset of the disease.

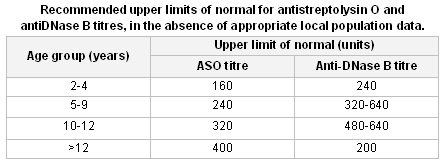

Anti-streptococcal serology: anti-streptolysin O and anti-DNase B titres. If the first test is not confirmatory, it should be repeated 10 to 14 days later. This is recommended in all cases of ARF, as throat cultures and rapid antigen tests are often negative.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal values for anti-streptolysin O (ASO) and anti-DNase B titresTable compiled by contributors. [Citation ends].

Rapid antigen tests: for group A Streptococcus (if available). It is important to note that rapid antigen tests may have poorer positive and negative predictive value for group A streptococcal pharyngitis compared with throat culture. Their use depends on the epidemiological context and rapid antigen tests may not be appropriate for use in high-incidence rheumatic fever populations when cultures can be performed.[70][71] Rapid antigen tests need local sensitivity and specificity testing.

Rapid molecular tests: for group A Streptococcus (if available). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays can be used at the point-of-care with sensitivity and specificity comparable to throat culture.[72][73][74] Use of molecular point-of-care testing has potential for wide application, especially in rural high-incidence settings.[75]

Echocardiogram

There are published morphological and Doppler findings that are typical of acute rheumatic carditis.[2]

Doppler findings in rheumatic valvulitis

Pathological mitral regurgitation (all 4 criteria met):

Seen in at least two views

Jet length ≥2 cm in at least one view

Peak velocity >3 m/s

Pansystolic jet in at least one envelope.

Pathological aortic regurgitation (all 4 criteria met):

Seen in at least two views

Jet length ≥1 cm in at least one view

Peak velocity >3 m/s

Pan diastolic jet in at least one envelope.

Morphological findings on echocardiogram in rheumatic valvulitis

Acute mitral valve changes

Annular dilation

Chordal elongation

Chordal rupture resulting in flail leaflet with severe mitral regurgitation

Anterior (or less commonly posterior) leaflet tip prolapse

Beading/nodularity of leaflet tips.

Chronic mitral valve changes (not seen in acute carditis)

Leaflet thickening

Chordal thickening and fusion

Restricted leaflet motion

Calcification.

Aortic valve changes in either acute or chronic carditis

Irregular or focal leaflet thickening

Coaptation defect

Restricted leaflet motion

Leaflet prolapse.

Diagnosing recurrent rheumatic fever

Recurrence of rheumatic fever, with or without evidence of established RHD, requires the same criteria as a primary episode. (i.e., 2 major manifestations, or 1 major plus 2 minor manifestations) or can be diagnosed with the presence of 3 minor manifestations. Diagnosis of recurrence requires evidence of a recent group A streptococcal infection. As with primary episodes, it is important that other diagnoses have been excluded.[1]

Demonstrating antecedent group A streptococcal infection

Evidence of antecedent group A streptococcal infection can be shown by demonstrating 1 of the following:

Elevated or rising streptococcal antibody titre

Positive throat culture

Positive rapid antigen test for group A streptococci (see comments above)

Recent scarlet fever.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer