Aetiology

Tapeworms are parasites of the taxonomic class Cestoda, and include the orders Pseudophyllidea and Cyclophyllidea. They divide their life cycles between two animal hosts.

Human infection with Taenia species occurs whenever undercooked beef (infected with T saginata cysticerci) or pork (infected with T solium cysticerci) is consumed. Cysticercosis occurs after humans accidentally ingest embryonated T solium eggs or gravid proglottids from T solium carriers. T solium carriers may contaminate water supplies or contaminate food directly, as sticky eggs under their fingernails can be transferred during food preparation, causing cysticercosis and/or neurocysticercosis in consumers.

Human infection with the dog tapeworm, Echinococccus granulosus, occurs through contact with infected dog (or other canid) faeces. Infection develops in dogs when they ingest organs of other animals harbouring tapeworm larvae, leading to infection with the adult tapeworm. Eggs are passed into the faeces of the dog and, if ingested by humans, can result in the development of complex cysts in tissue (metacestode larval form) and is termed echinococcosis.

Human infection with E multilocularis from foxes, canids, and occasionally cats also occurs through faecal-oral contact. Eggs are released in faeces and accidentally ingested by humans.

Human infection with Diphyllobothrium latum occurs when undercooked freshwater fish infected with the plerocercoid larvae of D latum is consumed. Humans are the main definitive host for D latum and the most important reservoir of infection. These tapeworms can be very large, measuring up to 12 metres and containing 3000 to 4000 proglottids. When eggs are discharged into freshwater, they hatch and release motile embryos, which are ingested by minute waterfleas (first intermediate hosts). Following ingestion of the waterfleas by larger crustaceans and fish (second intermediate hosts), these motile embryos develop into larvae (known as sparganum or plerocercoid larvae), which are infectious to humans. When raw or undercooked infected fish and crustaceans are eaten by humans, these larvae are ingested and develop into an adult tapeworm in the intestine.[2]

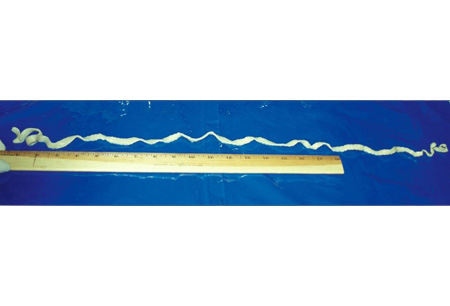

Human infection with Hymenolepis nana occurs when embryonated eggs from contaminated food, water, or hands or ingestion of infected insects results in infection. No intermediate host is required and person-to-person transmission can occur. The disease is most frequently encountered in small children. These eggs are immediately infectious, and both auto-infection and person-to-person transmission commonly occurs. Outbreaks in families are well described.[2][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Adult tapeworm identified as Taenia saginataFrom the personal collections of Dr Christina Coyle and Dr Maheen Saeed; used with permission [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

The presence of the adult tapeworm in the intestine can lead to malabsorption and malnutrition in the host. The presence of the larval form of the tapeworm in extra-intestinal tissues can lead to various symptoms and signs, including seizures (from cysts in the brain), hepatomegaly (from cysts in the liver), and cough and/or haemoptysis (from cysts in the lung).

Intestinal infection (e.g., with Diphyllobothrium latum, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia saginata)

Larvae are ingested, oncospheres (embryos) hatch, and adult tapeworms develop inside the human intestinal tract.

Both adult and larval forms may be present in the human intestinal tract (e.g., with H nana).

Adult parasites live in the human intestinal tract, and eggs and proglottids are passed in the faeces.

H nana oncospheres penetrate the bowel mucosa and develop into cysticercoid larvae. Larvae emerge in the bowel lumen after a period of 5 to 6 days, and develop into adult tapeworms in the ileum. About 20 to 30 days after initial infection, the adult begins to produce new eggs, which can be found in the faeces and spread the infestation.[2]

Cysticercosis and neurocysticercosis

Humans develop cysticercosis by ingesting embryonated T solium eggs or gravid proglottids. Following ingestion, oncospheres hatch and infect the small intestine or invade through the intestines and migrate to extra-intestinal tissues.

A minimal inflammatory reaction may occur with T saginata, suggesting that these tapeworms have an 'irritative' effect, perhaps causing clinical symptoms.

Embryos invade the bowel wall, and the scolex (tapeworm head with suckers, hooks, and a rudimentary body from which proglottids are produced by budding) of the larva evaginates, attaches to the upper jejunum, and develops into an adult worm.

Cysticerci (liquid-filled vesicles consisting of a membranous wall and a nodule containing the evaginated scolex) develop over a period of 3 weeks to 2 months.

Larvae may form within any extra-intestinal tissue. Neurocysticercosis is the invasion of the central nervous system.

Humans with cysticercosis are intermediate or dead-end hosts (i.e., do not transmit infection).

Once present in the parenchyma of host organs, cysts undergo dynamic changes. Initially cysts are vesicular and filled with clear fluid, and they may elicit a host inflammatory reaction (referred to as the cystic stage). The cysts start to degenerate and become turbid with an intense inflammatory reaction in surrounding tissue (referred to as the colloidal stage).[18] The granular stage is next, and is characterised by further degeneration when the cyst ultimately calcifies.

Neurocysticercosis can be parenchymal or extraparenchymal. Parenchymal disease used to be referred to as active (when the larva is viable) and inactive (when the larva is calcified), but that classification is no longer applicable. Magnetic resonance imaging studies have documented that patients with neurocysticercosis seizures and calcified lesions often have associated contrast enhancement and oedema. There has been increasing evidence that perilesional oedema, which occurs episodically, is associated with seizures. There is no evidence to suggest these lesions are associated with viable parasites. Instead, they may be caused by the release of antigens from the calcified granuloma in restimulation of host inflammation.

Extraparenchymal neurocysticercosis includes involvement of the subarachnoid space, the ventricles, the spinal cord, and/or the eye.

Another form of neurocysticercosis is referred to as racemose disease. It generally occurs when subarachnoid or intraventricular cysts proliferate in spite of scolex degeneration, provoking an intense inflammatory response from hosts.

Mixed neurocysticercosis involves both parenchymal and extraparenchymal disease.[19]

Echinococcosis (hydatiditis)

The life cycle of Echinococcus species involves definitive and intermediate hosts. Humans are accidental hosts.

Once ingested, oncospheres hatch from eggs in the small intestine.

Larvae penetrate the intestinal mucosa, then enter the blood and/or lymphatic system and migrate to visceral organs, where the metacestode (hydatid cyst) forms. Hydatid cysts are characterised by outer host reactions with acellular laminar and inner germinal membranes, forming the endocyst. Brood capsules with multiple protoscolices bud out from the germinal membrane.[1]

Hydatid cysts develop and enlarge into space-occupying lesions (metacestode stage) over months to years. Cystic echinococcosis (due to Echinococcus granulosus infection) or polycystic echinococcosis (due to E vogeli and E oligarthus infections) occurs when protoscolices form on the inside of the cystic wall. In alveolar echinococcosis (due to E multilocularis), discrete cysts are absent, and larvae expand by budding and invasive external growth out from the primary larval lesion.[1][2][19][20]

Classification

Taxonomy[1][2][3]

Phylum Platyhelminthes: class Cestoda, order Pseudophyllidea:

Diphyllobothrium latum

Adenocephalus pacificus (D pacificum)

D spirometra

Phylum Platyhelminthes: class Cestoda, order Cyclophyllidea:

Species:

Taenia

Hymenolepis

Bertiella

Dipylidium

Mesocestoides

Raillietina

Inermicapsifer

Echinococcus

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer