Approach

Ramsay Hunt syndrome involves a reactivation of the varicella zoster virus (VZV) along the course of the facial nerve, leading to sudden-onset (<72 hours) unilateral facial paralysis, severe ear/facial pain, and a vesicular rash, including blisters, involving the ear.[6] Additionally, the patient may have associated otological symptoms, including vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss.[1][9] Ramsay Hunt syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion: consider other causes of sudden-onset facial paralysis, such as Bell’s palsy, cerebrovascular accident, and Lyme disease, when evaluating patients.

The majority of patients presenting with Ramsay Hunt syndrome will recover their facial movement at least partially. Patients typically see improvement in facial movement within a few weeks to months of symptom onset. However, changes in facial symmetry and function can continue for up to a year before a patient’s exam stabilises. Recurrent Ramsay Hunt syndrome is exceedingly rare.[2]

History

Consider Ramsay Hunt syndrome in a patient presenting with the triad of:[1][9][12]

Sudden-onset (<72 hours) unilateral peripheral facial weakness (partial or complete, present in approximately 90% of patients)

Severe ear/facial pain

Vesicular lesions involving the pinna (present in approximately 41% of patients).

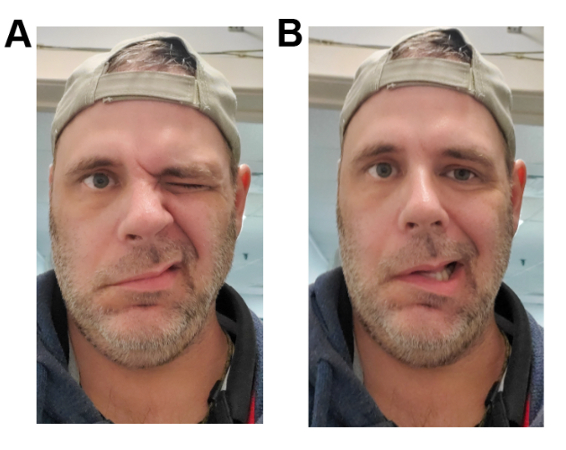

However, note that many patients do not present with all three classic symptoms as these do not always develop at the same time; vesicles can precede, coexist with, or follow facial palsy. The most suggestive symptom of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is unilateral peripheral facial palsy. Other presenting symptoms are vertigo, hearing loss, tinnitus, epiphora, altered taste, and oral lesions.[1][9][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Right facial palsy in a man with Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Note the inability to close the right eye (A) and significant smile asymmetry (B), both frequently seen in acute Ramsay Hunt syndromeFrom the collection of Dr Matthew Miller; used with permission [Citation ends].

Take a careful history. Ask about the following symptoms and features:

Onset and progression of the palsy

Otological symptoms (hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo) or prior otological surgery

Changes in the sense of taste, oral lesions

Dry eye.

Consider differential diagnoses such as Lyme disease if the patient reports presence of fever, general malaise, myalgia, erythema migrans (i.e., bull’s eye) rash, recalled tick bite, or recent travel to a Lyme disease-endemic region. Consider diagnoses such as facial nerve tumour if any of the following red flags are present in the history:

Gradual onset (>72 hours) facial weakness

Prior history of ipsilateral facial paralysis.

Also ask about risk factors for Ramsay Hunt syndrome:

Prior exposure to VZV (chickenpox, shingles), particularly in patients aged >50 years

Vaccination status - note that VZV vaccination was not widely available until the 1990s

Immunosuppression - people who are immunosuppressed are more susceptible to VZV infection

Physiological stress - a known risk factor for viral reactivation.[10]

Physical examination

Perform a focused neurological exam, a complete head and neck examination, and a detailed cranial nerve exam.

Ensure that parotid and/or neck masses are not present.

Document any cranial neuropathies, most notably dermatomal rash, facial weakness, and ocular findings. Sparing of brow function (i.e., ability to raise the eyebrow on the affected side) indicates an upper motor neuron lesion, as the dorsal division of the facial motor nucleus receives bilateral supranuclear efferent input.

Neural insult in Bell’s palsy occurs at the meatal foramen deep within the temporal bone; consequently all branches of the facial nerve are affected.

Uneven distribution of weakness across facial zones in the acute phase is highly suggestive of a tumour in the parotid or elsewhere along the course of the facial nerve and should prompt imaging studies.

Examination of the parotid gland includes palpation and visual examination of the oropharynx to rule out a deep lobe parotid tumour, which may displace the tonsil medially.

Perform a thorough visual and otoscopic evaluation to assess involvement of the external ear and ear canal.

The presence of vesicles, including blisters, in the external ear and auditory canal is highly suggestive of VZV reactivation in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. The vesicles may be seen on the external ear alone (around 41% of patients) or on both the external ear and external ear canal (around 25% of patients).[12] They may be associated with pain affecting the outer portion of the pinna and outer third of the external ear canal.[6] Some patients may present solely with redness of the skin in the ear canal and ear drum. Diffuse swelling of the soft tissue in the external ear canal may be present.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Painful vesicular rash in ear in a patient with Ramsay Hunt syndromeFrom the collection of Dr Matthew Miller; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: External acoustic meatus with multiple vesicular lesions in a patient with Ramsay Hunt syndromeAyoub F et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2017 Jul 13;2017:bcr20172198366; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: External acoustic meatus with multiple vesicular lesions in a patient with Ramsay Hunt syndromeAyoub F et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2017 Jul 13;2017:bcr20172198366; used with permission [Citation ends].

Examine the oral cavity, looking for vesicular eruptions on the cheek, tongue, and palate.

Vesicles, including blisters, are most commonly seen on the ear but may also be present on the above-mentioned areas.[6]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A) Vesicular rash on the tongue and B) the palate in a patient with Ramsay Hunt syndromeNeagu MR et al. Pract Neurol. 2016 Jun;16(3):232; used with permission [Citation ends].

Perform a thorough ophthalmic evaluation, including slit-lamp examination.[13]

Patients with ocular symptoms, especially if there is significant involvement in the V1 and V2 dermatomes in addition to facial weakness, are at risk for corneal injury. Keratitis may be present.

Some patients may present with a dry eye, due to the inability to close the eye.[6]

European expert consensus guidelines recommend referring the patient to an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist and a neurologist if there is involvement of the facial nerve and/or vestibulocochlear nerve, ear pain, and vertigo.[1] This allows for ENT and neurological follow-up and for treatment to be adjusted accordingly.[1]

Consider other diagnoses if any of the following red flags are present in the physical examination:

Uneven distribution of facial weakness across facial zones (e.g., preserved eyebrow movement suggests central paralysis from a cerebrovascular accident [CVA] or other causes)

Bilateral facial weakness

Presence of other cranial or peripheral neuropathies

Persistence of complete flaccid paralysis at 4 months from onset.

See Differentials.

Initial investigations

The diagnosis is typically clinical and no confirmatory tests are required. However, if there is uncertainty regarding aetiology, the vesicular lesions, if present, can be swabbed directly for confirmation by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A VZV DNA PCR has nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity.[1]

Other investigations

Consider electroneurography (ENoG), also known as evoked electromyography, in acute patients who present with near-complete or complete facial paralysis (i.e., House-Brackmann scale V or VI) to quantify the degree of neural degeneration.[14]

Request magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck in patients presenting with unilateral facial palsy and any red flag sign/symptom to rule out CVA and malignancy. Red flags include gradual onset weakness, other cranial or peripheral neuropathies, uneven distribution of weakness across facial zones, and prior history of ipsilateral facial weakness. CVA is the most important cause of facial paralysis that needs to be identified rapidly so treatment can be initiated. See Overview of stroke.

If the patient has been exposed to ticks or is in or has recently travelled to a Lyme-prevalent region, order Lyme serology (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] and Western blot). This is especially indicated if they present with suggestive symptoms such as fever, myalgia, and erythema migrans (i.e., bull’s eye rash).[15] See Lyme disease.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer