Recommendations

Urgent

Suspect CAP in patients with symptoms and signs of an acute lower respiratory tract infection and, in a hospital setting, with new radiographic shadowing (consolidation) for which there is no other explanation.[1][63][64][65]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, consider all patients with cough, fever, or other suggestive symptoms to have COVID-19 until proven otherwise. For patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia, see our topic Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Opens in new window.

Pneumonia due to COVID-19 is not covered in this topic.

Think ' Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in an adult patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[66][67]

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis.[67][68][69][70]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis. See Sepsis in adults.

Urgent: in hospital

Prioritise a chest radiograph for all patients with suspected CAP within 4 hours of presentation to hospital.[1][63][65]

Order blood tests including:[1][65]

Oxygen saturations to guide supportive treatment

Arterial blood gases in patients with SpO 2 <94%, those with a risk of hypercapnic ventilatory failure (CO 2 retention), and all patients with high-severity CAP (see our Management - recommendations section for more detail on assessing severity)

Urea and electrolytes to inform severity

Full blood count, liver function tests, and C-reactive protein to aid diagnosis and for baseline measurements.

Assess oxygen requirements. Prescribe oxygen if oxygen saturation <94% and maintain at target range.[1][65] In patients at risk of CO 2 retention prescribe oxygen if oxygen saturation <88%.[71]

Monitor controlled oxygen therapy. An upper SpO 2 limit of 96% is reasonable when administering supplemental oxygen to most patients with acute illness who are not at risk of hypercapnia.

Evidence suggests that liberal use of supplemental oxygen (target SpO 2 >96%) in acutely ill adults is associated with higher mortality than more conservative oxygen therapy.[72]

A lower target SpO 2 of 88% to 92% is appropriate if the patient is at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure.[71]

Assess mortality risk using the CURB-65 score and your clinical judgement for all patients with pneumonia confirmed by chest radiography (see our Management - full recommendations section for more information). [ CURB-65 pneumonia severity score Opens in new window ] [1][63][65]

Score of 3-5: high-severity.

Score of 2: manage as moderate-severity pneumonia.[1][63][65]

Score of 0 or 1: manage as low-severity pneumonia.[1][63][65]

Send sputum and blood samples for culture in people with moderate- or high-severity CAP, ideally before starting antibiotics.[1][65] Consider legionella and pneumococcal urine antigen testing.[63]

Measure observations initially at least twice daily, and more frequently (e.g., every hour) in those admitted to a critical care unit (high-dependency unit or intensive care unit).[1][65]

Urgent: in the community

Perform a chest radiograph ONLY if you are unsure of the diagnosis and radiography will help you to manage the acute illness.[1][63][65]

Use pulse oximetry as part of your assessment of disease severity and to determine oxygen requirement.[71]

Assess mortality risk using the CRB-65 score (see Management - full recommendations) and your clinical judgement to inform severity.[1][63][65]

Key Recommendations

Presentation

Patients with CAP typically present with symptoms and signs consistent with a lower respiratory tract infection (i.e., cough, dyspnoea, pleuritic chest pain, mucopurulent sputum, myalgia, fever) and no other explanation for the illness (e.g., sinusitis or asthma).[63]

Remember to consider atypical presentations (without obvious chest signs). For example:

Mycoplasma pneumonia in young adults may present as sore throat, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea[73]

Legionella pneumonia may present as constitutional upset, diarrhoea, and confusion[73]

Pneumocystis pneumonia in immunosuppressed people may present only as cough, dyspnoea, and marked hypoxia[73]

Older people frequently present with non-specific symptoms (especially confusion) and worsening of pre-existing conditions, and without chest signs or fever[1][65]

Some people present with acute confusional states.[73]

Do not use clinical features alone to predict the causative agent or to influence your initial choice of antibiotic.[1][65][74]

Risk stratification

Determine whether the patient should be managed in hospital or at home using the CURB-65 mortality risk score (hospital setting) or CRB-65 score (community setting) (see our Management - recommendations section for more detail on risk stratification). [ CURB-65 pneumonia severity score Opens in new window ] [1][63][65]

Risk stratification in hospital*

Severity of CAP | CURB-65 score | Management decision |

|---|---|---|

High | 4 or 5 | Arrange emergency assessment by a critical care specialist[1][63][65] |

3 | Discuss with senior colleague at the earliest opportunity and manage as high-severity pneumonia[1][63][65] | |

Moderate | 2 | Consider for short-stay inpatient treatment or hospital-supervised outpatient treatment[1][63][65] |

Low | 0 or 1 | |

*All patients with CAP confirmed by chest radiograph. | ||

Risk stratification in the community

Severity of CAP | CRB-65 | Management decision |

|---|---|---|

High | 3 or more | |

Moderate | 1 or 2 | Consider hospital referral for assessment and treatment*[1][63][65] |

Low | 0 |

Imaging

Confirm the diagnosis by chest radiograph in all patients presenting to hospital with suspected CAP.[1][63][65]

A definitive diagnosis of CAP requires evidence of consolidation on chest x-ray.[75]

In community settings base the diagnosis on signs and symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection, focal chest signs, and illness severity.[1][63][65]

Further investigations

Discuss with a senior colleague any patient who does not improve as expected.[1][65]

Consider repeat chest radiograph, C-reactive protein, white cell count, and further specimens for microbiology in patients not progressing satisfactorily after 3 days of treatment.[1][65]

In patients with high-severity CAP who do not respond to beta-lactam antibiotics or in whom you suspect an atypical or viral pathogen, order polymerase chain reaction (or other antigen detection test) of sputum or other respiratory tract sample.[1][65]

In the community assess oxygenation via pulse oximetry.[71]

Oxygen saturation <94% is an adverse prognostic factor in CAP and also usually an indication for oxygen therapy.[76]

General investigations are not necessary in the majority of patients presenting in the community, but you should consider a point-of-care C-reactive protein test if you cannot make a diagnosis of CAP from the clinical assessment and you are not sure whether antibiotics are indicated.[1][63][65]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, order a nucleic acid amplification test, such as real-time PCR, for SARS-CoV-2 in any patient with suspected infection whenever possible.[77][78] See our topic Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Opens in new window.

No constellation of signs and symptoms is predictive of CAP. However, patients typically present with:[1][63][64][65]

Symptoms and signs consistent with a lower respiratory tract infection:

Cough and at least one other respiratory tract symptom:

At least one systemic feature:

New focal chest signs on examination such as crackles or bronchial breathing

No other explanation for the illness.

Remember to consider atypical presentations of CAP (i.e., without obvious chest signs). For example:

Mycoplasma pneumonia in young adults may present as sore throat, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea[73]

Legionella pneumonia may present as constitutional upset, diarrhoea, and confusion[73]

Pneumocystis pneumonia in the immunosuppressed may present only with cough, dyspnoea, and marked hypoxia[73]

Older people frequently present with non-specific symptoms (e.g., lethargy, malaise, anorexia, confusion) and worsening of pre-existing conditions, and without chest signs or fever[1]

Some people present with acute confusional states.[73]

Consider speed of symptom onset in your differential diagnosis:

Symptoms developing within minutes may be suggestive of pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, or a cardiac aetiology.

Practical tip

Think ' Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in an adult patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[66][67][68] See Sepsis in adults .

The patient may present with non-specific or non-localised symptoms (e.g., acutely unwell with a normal temperature) or there may be severe signs with evidence of multi-organ dysfunction and shock.[66][67][68]

Remember that sepsis represents the severe, life-threatening end of infection.[79]

Pneumonia is one of the main sources of sepsis.[80]

Use a systematic approach (e.g., National Early Warning Score 2 [NEWS2]), alongside your clinical judgement, to assess the risk of deterioration due to sepsis.[66][68][69][81] Consult local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution.

Arrange urgent review by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis:[70]

Within 30 minutes for a patient who is critically ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 7 or more, evidence of septic shock, or other significant clinical concerns).

Within 1 hour for a patient who is severely ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 5 or 6).

Follow your local protocol for investigation and treatment of all patients with suspected sepsis, or those at risk. Start treatment promptly. Determine urgency of treatment according to likelihood of infection and severity of illness, or according to your local protocol.[70][81]

In the community: refer for emergency medical care in hospital (usually by blue-light ambulance in the UK) any patient who is acutely ill with a suspected infection and is:[67]

Deemed to be at high risk of deterioration due to organ dysfunction (as measured by risk stratification)

At risk of neutropenic sepsis.

Some symptoms and signs are more common with specific pathogens.[1]

Do not, however, use clinical features alone to predict the causative agent or to influence your initial choice of antibiotic.[1][65][74]

Typical pathogens causing CAP in adults in the UK and their most commonly associated features[1]

Pathogens | Most commonly associated clinical features | Other features |

|---|---|---|

Streptococcus pneumoniae | Acute onset, high fever, and pleuritic chest pain | Most common overall pathogen More likely in the presence of cardiovascular comorbidity, increasing age Bacteraemic S pneumoniae is more likely in:

|

Haemophilus influenzae | No specific defining features | More likely in older people and those with COPD |

Legionella pneumophila | Diarrhoea, encephalopathy and other neurological symptoms, severe infection more likely and evidence of multisystem involvement (e.g., abnormal liver function tests, elevated serum creatine kinase) | More likely in young patients without comorbidities, smokers, immunocompromised people, people exposed to contaminated artificial water systems (e.g., air conditioning units, spas, fountains, repair of domestic plumbing systems) Higher frequency in severe illness (patients in the intensive care unit) Enquire about foreign travel |

Staphylococcus aureus | No specific defining features | More likely if preceding or concurrent influenza infection Higher frequency in severe illness (patients in the intensive care unit) Enquire about influenza symptoms as they are of predictive value. Influenza virus infection can be complicated by co-/secondary infection with S aureus |

Atypical pathogens causing CAP in adults in the UK and their most commonly associated features[1]

Pathogens | Most commonly associated clinical features | Other features |

|---|---|---|

Mycoplasma pneumoniae | In young adults may present as sore throat, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea[73] | More likely in younger patients Epidemic years occur in roughly 4-yearly cycles |

Chlamydophila pneumoniae | No specific defining features | None |

Coxiella burnetii | History of dry cough and high fever | More likely in males Exposure to infected animal sources (especially during parturition) is the main epidemiological link[82] |

Klebsiella pneumoniae | No specific defining features | People with alcohol dependency are at higher risk of bacteraemic and fatal Klebsiella pneumonia |

Your history should cover risk factors to help you assess whether the patient has CAP, a lower respiratory tract infection, or an alternative diagnosis. You should also identify factors that may influence the management plan if CAP is diagnosed.

Be aware that you cannot make a definitive diagnosis of CAP from the history alone.

Medical history

(*Denotes a strong risk factor for CAP.)

Respiratory chronic diseases:

Other chronic comorbidities:

Practical tip

Consider aspiration pneumonitis/pneumonia in patients at high risk of aspiration, such as those with chronic swallowing difficulties, those with organic neurological conditions (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, stroke, dementia), or those who cannot protect their airways easily.[1]

Social history

Age ≥65 years*

Incidence of CAP increases significantly with age. Advanced age is associated with a higher mortality from CAP.[10]

Residence in a nursing home*

Contact with children*

Regular contact with children is associated with an increased risk of CAP.[49]

CAP is more severe in males than in females, leading to higher mortality in males overall and especially those of older age.[86]

Lifestyle history

Alcohol use/misuse*

Smoking*

Poor oral hygiene

Poor oral hygiene (particularly dental dysaesthesia and wearing dental prostheses) may contribute to a higher risk of CAP in adults.[87]

Drug history

Proton pump inhibitors, H2 antagonists, and prescribed opioids (particularly immunosuppressive opioids) are associated with CAP.[59]

Carry out a thorough examination, particularly of the cardio-respiratory system, to identify features consistent with CAP.

Check for:

Fever (>38ºC [>100ºF])

Raised respiratory rate

Tachycardia

Focal chest signs – none, some, or all of these may be present:

Crackles

Bronchial breathing

Decreased chest expansion

Dullness to percussion (suggests consolidation and/or pleural effusion)

Decreased entry of air.

Focus in addition on other areas (e.g., throat, legs) if the presentation suggests an alternative diagnosis, such as an upper respiratory tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism.

In hospital

All patients on presentation

Send all patients seen in hospital with suspected CAP for a chest radiograph as soon as possible to confirm the diagnosis, and within 4 hours of presentation to hospital.[1][63][65]

New shadowing (consolidation) on chest x-ray confirms the diagnosis of CAP [1][63][65]

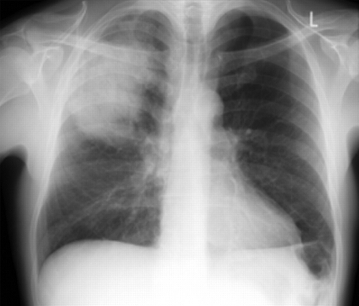

Reassess the patient if the chest x-ray shows no consolidation.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior chest radiograph showing right upper lobe consolidation in a patient with community-acquired pneumoniaDurrington HJ, et al. Recent changes in the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. BMJ 2008;336:1429. [Citation ends].

Practical tip

A high-quality chest radiograph is important to ensure accurate diagnosis and to avoid inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. One study reported that 29% of hospitalised patients treated for CAP did not have radiographic abnormalities.[88]

Bear in mind that it is more difficult to obtain a high-resolution image from a person with class III obesity (body mass index ≥40).

Reserved for specific circumstances

Consider a chest computed tomography (CT) scan if the radiograph is of poor quality or an ill-defined consolidation is present.[1]

Consider a chest CT scan or other imaging investigations for 'complicated' pneumonia or atypical changes on a chest radiograph, such as cavitation, multifocal consolidation pattern, or pleural effusion.[89][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest radiograph showing left upper lobe cavitating pneumoniaFrom the collection of Dr Jonathan Bennett. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left-sided pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr R Light. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Increased opacification of the right perihilar region and superior segment of the right lower and upper lobes consistent with worsening aspiration pneumoniaFrom the collection of Dr Roy Hammond. Used with permission [Citation ends].

X-ray findings | Further imaging | Consider alternative diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

Cavitation | Chest CT scan |

|

Multifocal consolidation (note that it is the multifocal nature, not the consolidation that is the distinguishing feature) | Chest CT scan |

|

Pleural effusion | Chest ultrasound +/- guided aspiration +/- chest CT scan |

|

Practical tip

‘Complicated’ pneumonia refers to pneumonia that is complicated by the presence of parapneumonic effusion (an exudative pleural effusion associated with pulmonary infection), empyema (pus in the pleural space), abscess, pneumothorax, necrotising pneumonia, or bronchopleural fistula.

Around 40% of people who are hospitalised for pneumonia develop parapneumonic effusion.[90] Empyema is a type of pleural effusion that is difficult to distinguish from a parapneumonic effusion on chest radiograph.

Findings on a CT scan suggestive of a parapneumonic effusion (as opposed to empyema) include:[91]

Usually small volume

Normal meniscus sign

Dependent

No loculation.

Split pleura sign’ is not typical and is more specific for empyema.

Consider CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) to rule out pulmonary embolism if symptoms came on quickly (within minutes) or pain and breathlessness preceded infective symptoms.[92]

In the community

Do not request a chest radiograph for patients with suspected CAP seen in the community unless:[1][63][65]

There is diagnostic doubt

The patient is deemed to be at risk of underlying lung pathology (e.g., they have risk factors for lung cancer)

Progress following treatment is not satisfactory at review.

In community settings base the diagnosis on signs and symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection, focal chest signs, and illness severity.[1][63][65]

Debate: Ultrasound in the diagnosis of CAP

Although a chest radiograph showing new shadowing that cannot be attributed to any other cause is the ‘gold-standard’ for the diagnosis of pneumonia, it may not always be feasible in a community setting and it involves exposure to radiation.

Emerging evidence has shown that lung ultrasound is a possible accurate diagnostic test for people with CAP. However, the benefits of its use in practice over chest radiography are still unclear.

A meta-analysis of 12 studies looking at the diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasound in people with CAP found a sensitivity and specificity of 0.88 and 0.86, respectively.[93] However, there were limitations, such as the large variability in the findings and the lack of heterogeneity of the studies reviewed.

Further evidence is required before recommendations can be made.

General investigations

In a hospital setting

Arrange the following tests for all patients admitted to hospital.

Start with oxygen saturations and urea (and electrolytes) as these will inform supportive treatment and severity, respectively:[1][65]

Pulse oximetry (preferably while breathing air) to assess oxygenation saturations.

Oxygen saturation <94% is an adverse prognostic factor in patients with CAP and may be an indication for oxygen therapy.[76]

Arterial blood gas (ABG) measurements in patients receiving oxygen therapy.[71]

Measure ABG in patients with SpO 2 <94% , those with a risk of hypercapnic ventilatory failure (CO 2 retention), and all patients with high-severity CAP.[1]

Urea (and electrolytes) to inform severity of disease.

Practical tip

Always record the inspired oxygen concentration clearly as this is essential for interpreting blood gas results.

Order full blood count, C-reactive protein, and liver function tests to help identify underlying or associated pathology, and for baseline measurements.[1][65]

Full blood count . Leukocytosis is often seen in people with CAP:

A white cell count of >15 x 10 9/L indicates a bacterial (particularly pneumococcal) aetiology.[1]

C-reactive protein (CRP) to help rule out other acute respiratory illnesses and as a baseline measure:

A level >100 mg/L makes pneumonia likely[94]

High levels of CRP do not necessarily indicate that pneumonia is bacterial or SARS-CoV-2, but low CRP levels make a secondary bacterial infection less likely.[95]

A level <20 mg/L with symptoms for more than 24 hours makes the presence of pneumonia highly unlikely[94]

A failure of CRP to fall by 50% or more at day 4 is associated with an increased risk for 30-day mortality, need for mechanical ventilation and/or inotropic support, and complications.[96]

Liver function tests to assess liver function:

Consider ordering serum procalcitonin. Baseline procalcitonin is increasingly being used in critical care settings and in the emergency department to guide decisions on antibiotic treatment in patients with highly suspected sepsis and in those with suspected bacterial infection.[81][97][98][99][100]

Increased values of procalcitonin are correlated with bacterial pneumonia, whereas lower values are correlated with viral and atypical pneumonia. Procalcitonin is especially elevated in cases of pneumococcal pneumonia.[101][102]

Procalcitonin is a peptide precursor of calcitonin, which is responsible for calcium homeostasis. It is currently excluded from key guidelines, but increasingly used in practice.

Perform early thoracocentesis in all patients with pleural effusion as this can reveal an infected pleural space consistent with a parapneumonic effusion or empyema.[1][65]

Drain pleural fluid in patients with an empyema or clear pleural fluid with pH <7.2.[1]

Monitoring

Measure observations initially at least twice daily, and more frequently (e.g., every hour) in patients admitted to a critical care unit (high-dependency unit or intensive care unit).[1][65]

Pulse

Blood pressure

Respiratory rate

Temperature

Blood pressure

Oxygen saturation (with a recording of the inspired oxygen saturation at the same time)

Mental status.

All patients with high-severity CAP (high risk of death) should be reviewed at least every 12 hours until improvement.[1][65] This should be done by a senior colleague and the medical team.[1][65]

In the community

General investigations are not necessary for the majority of patients with CAP who are managed in the community.[1][65] However, you should consider a point-of-care C-reactive protein (CRP) if you cannot make a diagnosis of CAP from the clinical assessment and it is not clear whether antibiotics should be prescribed.[63]

Assess oxygenation via pulse oximetry.[71]

Oxygen saturation <94% is an adverse prognostic factor in CAP and also may be an indication for oxygen therapy.[76]

Microbiological investigations

Be aware that the extent of microbiological testing in an individual patient is guided by severity, presence of risk factors (e.g., COPD) , and disease outbreaks (e.g., legionella pneumonia).[1][65]

In hospital

Do not perform microbiological tests routinely in patients with low-severity CAP presenting in hospital.[1][65] Empirical antibiotic therapy is associated with a good prognosis in these patients.[1]

Blood cultures

Order blood cultures, ideally before antibiotics are given, in all patients with moderate- or high-severity CAP (as determined by the CURB-65 score – see our Management recommendations section).[1][63][65]

Isolation of bacteria can be highly specific in determining the microbial aetiology in people with moderate or severe CAP.[1][63][65]

Bacteraemia is also a marker of illness severity. However, many patients with CAP do not have associated bacteraemia.[1] Microbial causes of CAP that can be associated with bacteraemia include:[1]

Do not order blood cultures in patients with confirmed CAP who have low-severity disease and no comorbid conditions.[1][65]

Debate: Blood cultures

There is debate around the practicality of ordering routine blood cultures in patients hospitalised with CAP. This is mainly due to low sensitivity, cost, and the fact that results rarely influence antimicrobial management.

In a study of 355 patients admitted to hospital for CAP, the proportion of false-positive blood cultures was 10%, and the proportion of true positives was 9% (95% CI, 3.3% to 5.5%).[104]

Antibiotic therapy was changed on the basis of blood culture results in only 5% of patients (95% CI, 3% to 8%).[104]

However, despite these limitations, most experts still recommend blood cultures in patients with high-severity CAP.[1]

Sputum cultures

Send sputum cultures in:

All patients with moderate- or high-severity CAP (as determined by CURB-65 score).[63] The British Thoracic Society recommends sputum cultures in patients with moderate-severity CAP only if they have not received prior antibiotic therapy[1][65]

Patients who do not improve regardless of disease severity (sputum or other respiratory samples).[1][65]

Gram stain of sputum cultures

Order Gram stain of sputum cultures in patients with high-severity CAP or complications if available in your local laboratory.[1][65]

Gram stain is an immediate indicator of the likely pathogen and can help with interpreting culture results.[1][65]

Evidence: sputum Gram stain

A prospective study of 1390 patients with bacteraemic CAP found a sensitivity for sputum Gram stain of:[105]

82% for pneumococcal pneumonia

79% for H influenzae pneumonia

76% for staphylococcal pneumonia.

Specificities ranged from 93% to 96%.

Practical tip

Carrying out routine sputum Gram stains for all patients is unnecessary.[1] The test has a low sensitivity and specificity, and often does not contribute to initial management. Problems include:[1]

Patients may not be able to produce good specimens

Prior exposure to antibiotics

Delays in transport and processing of samples, which reduces the yield of bacterial pathogens

Difficulty interpreting the results due to contamination of the sample by upper respiratory tract flora, which may include potential pathogens such as S pneumoniae and ‘coliforms’ (especially in patients already given antibiotics).

Urine antigen testing

Consider pneumococcal urine antigen tests for people with moderate- or high-severity CAP.[63]

Urine antigen testing is useful for diagnosing pneumococcal pneumonia in adults and is less affected than blood/sputum cultures by prior antibiotic therapy.[1][65]

Evidence: Urine antigen testing for pneumococcal pneumonia

Studies have shown significantly greater sensitivity rates for the pneumococcal urine antigen test than for routine blood or sputum cultures.[106]

Results remain positive in 80% to 90% of patients for up to 7 days after starting antimicrobial treatment.[106]

Debate: Patient groups for pneumococcal testing

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines differ in their recommendations regarding who should be tested for pneumococcal pneumonia using urine antigen.

The BTS recommends testing all patients with high-severity CAP,[1] whereas NICE recommends considering testing in patients with moderate- or high-severity CAP.[63][65]

A later comparison by the BTS of the key recommendations in the two guidelines (BTS published in 2009 and NICE in 2014) concluded that there were no major differences between them and, where there were differences, clinicians should follow the NICE guideline instead of the BTS guideline.[107]

Order legionella urine antigen tests in all patients with specific risk factors and for all patients with CAP during outbreaks.[1][65] Consider testing also for people with moderate- or high-severity CAP.[63]

It is important that legionella pneumonia is diagnosed promptly as it is associated with significant mortality and has public health significance.[1][65]

Detection of Legionella pneumophila urinary antigen by enzyme immunoassay allows for rapid results early in the illness.[1][65]

Legionella antigen testing by enzyme immunoassay is highly specific (>95%) and sensitive (80%) for detecting L pneumophila serogroup 1, which is the most common cause of sporadic CAP and CAP due to foreign travel in the UK.[108]

Debate: Patient groups for legionella testing

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines differ in their recommendations regarding the patient groups that should be tested for legionella pneumonia using urine antigen.

The BTS recommends testing only patients with high-severity CAP, patients with risk factors, and all patients with CAP during outbreaks,[1] whereas NICE recommends that clinicians consider testing in people with moderate- or high-severity CAP.[63][65]

A later comparison by the BTS of the key recommendations in the two guidelines (BTS published in 2009 and NICE in 2014) concluded that there were no major differences between them and, where there were differences, clinicians should follow the NICE guideline instead of the BTS guideline.[107]

In the comparison, the BTS also stated that its recommendation to test for legionella in patients with risk factors and all patients with CAP during outbreaks remains valid as this was not examined by NICE.[107]

If the legionella urine antigen test is positive remember to order sputum cultures from respiratory samples (e.g., obtained from bronchoscopy) for Legionella species. This is to aid outbreak and source investigation to prevent further cases.[1][65]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serological tests

Use PCR of sputum or other respiratory tract samples for respiratory viruses (influenza A and B, parainfluenza 1-3, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus) and atypical pathogens ( Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Chlamydophila psittaci, Coxiella burnetii, and Pneumocystis jirovecii [if at risk]) in patients with high-severity CAP:[1][65]

If unresponsive to beta-lactam antibiotics

If there is a strong suspicion of an ‘atypical’ pathogen.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, order a nucleic acid amplification test, such as real-time PCR, for SARS-CoV-2 in any patient with suspected infection whenever possible.[77][78] See our topic Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Opens in new window

Differentiating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia from COVID-19 is not usually possible from signs and symptoms. However, patients with bacterial pneumonia are more likely to have rapid development of symptoms and purulent sputum. They are less likely to have myalgia, anosmia, or pleuritic pain.[109]

Consider urine antigen, PCR of upper (e.g., nose and throat swabs) or lower (e.g., sputum) respiratory tract samples, or serological investigations in patients with moderate- or low-severity CAP:[1]

During outbreaks (e.g., Legionnaires’ disease)

During mycoplasma epidemics, or

When there is a particular clinical or epidemiological reason

If available, PCR is preferred over serological investigations.

In the community

Do not order microbiological tests routinely in patients presenting with CAP in the community as:[1][63][65]

These patients are not usually severely ill and are at low risk of death[1]

Delays in transport of specimens to laboratory reduces the yield of bacterial pathogens (especially S pneumoniae) from sputum cultures, and results are often received too late by the general practitioner to have any impact on initial management.[1]

Only consider ordering microbiological tests in the community if:[1][65]

The patient’s symptoms do not improve with empirical antibiotic therapy

Consider sputum examination

The patient has a persistent productive cough, especially if they also have malaise, weight loss, or night sweats, or risk factors for tuberculosis (e.g., ethnic origin, social deprivation, older patients, previous history of tuberculosis, contact history of tuberculosis)

Consider sputum examination for Mycobacterium tuberculosis

There is a clinical or epidemiological reason, such as an outbreak (e.g., Legionnaires’ disease) or during mycoplasma epidemics

During the COVID-19 pandemic, order a nucleic acid amplification test, such as real-time PCR, for SARS-CoV-2 in any patient with suspected infection whenever possible.[77][78] See our topic Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Opens in new window

Summary of the recommendations for microbiological investigations from the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[1][63][65]

CAP severity and treatment site | Preferred microbiological tests |

|---|---|

High-severity (CURB-65 = 3-5; CRB-65 = 3-4): treat in hospital |

|

Moderate-severity (CURB-65 = 2; CRB-65 = 1-2): treat in hospital |

|

Low-severity (CURB-65 = 0-1; CRB-65 = 0): treat at home or in hospital |

|

*If available, PCR is preferred over serological investigations.[1][65] | |

Practical tip

In routine clinical practice, pathogens are identified only in about one third to one quarter of patients with CAP admitted to hospital.[1] Despite this, identifying the causative organism of CAP and sensitivity patterns is important because it:[1]

Allows for appropriate selection of antibiotic regimens. Change to targeted and narrow-spectrum antibiotic therapy is recommended once the pathogen is identified unless there are concerns of dual infection

Detects certain pathogens with public health significance and/or those that cause serious conditions that require different treatment from standard empiric antibiotics. These include:

Legionella species

Influenza A and B, including avian influenza A H5N1 and avian influenza A H7N9

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)

Community-associated methicillin-resistant S aureus (CA-MRSA)

Agents of bioterrorism

Other emerging pathogens

Allows for monitoring of the spectrum of organisms that cause CAP over time. This is important to establish sensitivity patterns.

In hospital

Discuss with a senior colleague any patient who does not improve as expected.[1]

Consider repeat chest radiograph, C-reactive protein (CRP), white cell count, and further specimens for microbiology in patients not progressing satisfactorily after 3 days of treatment.[1][65]

A failure of CRP to fall by 50% or more at day 4 is associated with an increased risk for 30-day mortality, need for mechanical ventilation and/or inotropic support, and complications.[96]

Practical tip

Pointers to clinical improvement:[1][65]

Resolution of fever for >24 hours

Pulse rate <100 beats/minute

Resolution of tachypnoea

Clinically hydrated and taking oral fluids

Resolution of hypotension

Absence of hypoxia

Improving white cell count

Non-bacteraemic infection

No microbiological evidence of legionella, staphylococcal, or gram-negative enteric bacilli infection

No concerns over gastrointestinal absorption.

Consider referral to a respiratory physician.[1][65]

In patients with high-severity CAP who are not responding to beta-lactam antibiotics or for whom an atypical or viral pathogen is suspected, order PCR (or other antigen detection test) of sputum or other respiratory tract sample.[1][65]

In the community

Assess oxygenation via pulse oximetry.[71]

Do not request a repeat chest radiograph before discharge from hospital in patients who have recovered satisfactorily from CAP.[1][65]

Request a repeat chest radiograph during recovery after about 6 weeks for patients (regardless of whether they have been admitted to hospital):[1][65]

With persisting symptoms or physical signs

Who are at higher risk of underlying malignancy (especially people who smoke and those aged >50 years).

Practical tip

Resolution of radiographic changes occurs relatively slowly after CAP and lags behind clinical recovery.[1]

Consider bronchoscopy in patients with persisting signs, symptoms, and radiological abnormalities at around 6 weeks after completing treatment.[1][65]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer