Pancreatic cancer most commonly presents late with advanced disease. Symptoms include unexplained upper abdominal pain, painless obstructive jaundice, weight loss, and, in later stages, back pain. All patients with suspected pancreatic cancer should be investigated and managed, without delay, in a framework of specialist teams to ensure prompt diagnosis and early treatment.

History and physical examination

Physicians should consider pancreatic cancer in any patient who presents with unexplained upper abdominal pain, painless obstructive jaundice, weight loss, and back pain. Pancreatic cancer may present as early or advanced disease.

Early disease

In early stages, when there is no obstruction of the biliary tract, the disease presents with non-specific symptoms such as malaise, abdominal pain, nausea, or weight loss.[36]Bond-Smith G, Banga N, Hammond TM, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMJ. 2012 May 16;344:e2476.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22592847?tool=bestpractice.com

Advanced disease

In more advanced disease, tumours in the head of the pancreas often obstruct the common bile duct, presenting with symptoms of obstructive jaundice such as pale stool, dark urine, and/or pruritus. Tumours in the body and tail tend to present later and more often with pain, usually epigastric with radiation to the back; jaundice in these patients is usually caused by hepatic or hilar metastases. Persistent back pain is associated with retroperitoneal metastases.

Extensive pancreatic infiltration or obstruction of the major pancreatic ducts will also cause exocrine dysfunction, resulting in malabsorption and steatorrhoea or an unexplained episode of pancreatitis. Endocrine dysfunction, resulting in new-onset diabetes presenting with thirst, polyuria, nocturia, and weight loss, is present in 20% to 47% of patients.[37]Pannala R, Basu A, Petersen GM, et al. New-onset diabetes: a potential clue to the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Jan;10(1):88-95.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2795483

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19111249?tool=bestpractice.com

Pancreatic cancer should be considered in adult patients (aged 50 years of age or older) with new-onset diabetes but without predisposing features or a positive family history for diabetes mellitus.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[5]Chari ST, Leibson CL, Rabe KG, et al. Probability of pancreatic cancer following diabetes: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005 Aug;129(2):504-11.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(05)00877-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16083707?tool=bestpractice.com

Other signs of advanced disease include weight loss, anorexia, fatigue, an abdominal mass in the epigastrium, hepatomegaly, a positive Courvoisier's sign (painless palpable gallbladder and jaundice), or signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation: petechiae, purpura, bruising. A large tumour or peritumoural oedema may compress the stomach or duodenum, leading to nausea and early satiety.[36]Bond-Smith G, Banga N, Hammond TM, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMJ. 2012 May 16;344:e2476.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22592847?tool=bestpractice.com

Because patients with pancreatic cancer have an increased risk of thromboembolic disease, venous thrombosis or migratory thrombophlebitis (Trousseau's sign) could also be a first presentation of pancreatic cancer.[7]Diaconu C, Mateescu D, Bălăceanu A, et al. Pancreatic cancer presenting with paraneoplastic thrombophlebitis--case report. J Med Life. 2010 Jan-Mar;3(1):96-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20302205?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Trousseau's sign in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinomaPunithakumar EJ et al. Trousseau syndrome in pancreatic carcinoma. Surgery. 2021;169(2):E3-4; used with permission [Citation ends].

Laboratory tests

There are no blood tests diagnostic for pancreatic cancer. Laboratory investigations appropriate to perform in the diagnostic work-up include the following.

Liver function tests (LFTs): abnormal LFTs are associated with the degree of obstructive jaundice but cannot distinguish biliary obstruction (of any cause) from liver metastases.[38]Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;112(1):18-35.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2017/01000/ACG_Clinical_Guideline__Evaluation_of_Abnormal.13.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27995906?tool=bestpractice.com

Biomarkers: available biomarkers, such as cancer antigen (CA)19-9 or carcinoembryonic antigen, lack the desired sensitivity and specificity for early detection.[39]Harsha HC, Kandasamy K, Ranganathan P, et al. A compendium of potential biomarkers of pancreatic cancer. PLoS Med. 2009 Apr 7;6(4):e1000046.

https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000046

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19360088?tool=bestpractice.com

CA19-9 has a sensitivity of 70% to 90% and a specificity of 90%. False-positive results are often obtained in benign obstructive jaundice or chronic pancreatitis. CA19-9 is particularly useful as an aid in preoperative staging, in identifying recurrence in patients who have undergone resection, and in assessing the response to treatment in advanced disease.[18]Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007 Aug;56(8):1134-52.

https://academic.oup.com/pmj/article/84/995/478/7026385

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17625148?tool=bestpractice.com

However, using CA19-9 on its own to predict surgical resectability is not recommended.[40]Benke M, Farkas N, Hegyi P, et al. Preoperative serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels cannot predict the surgical resectability of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2022;28:1610266.

https://www.por-journal.com/articles/10.3389/pore.2022.1610266/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35645620?tool=bestpractice.com

Clotting profile and full blood count (FBC): a derangement of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors will cause a prolonged prothrombin time. An FBC and clotting profile should be performed before any invasive diagnostic procedure.

Non-invasive imaging

Computed tomography (CT) is used to diagnose and stage pancreatic cancer, and to determine whether a tumour is resectable.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[41]Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, et al. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023 Nov;34(11):987-1002.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(23)00824-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37678671?tool=bestpractice.com

Pancreatic protocol CT scan

All patients with an initial suspicion of pancreatic cancer should undergo assessment by dynamic-phase helical or spiral CT) according to a specific pancreas protocol (i.e., triphasic cross-sectional imaging and thin slices, and in the specific aspect of venous phase of intravenous contrast).[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[42]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pancreatic cancer in adults: diagnosis and management. Feb 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng85

[43]Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Cinar P, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Aug 5:JCO2001364.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.20.01364?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32755482?tool=bestpractice.com

This has been shown to achieve diagnostic rates of 97% for pancreatic cancer, with accurate prediction of resectability in 80% to 90% of patients.[18]Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007 Aug;56(8):1134-52.

https://academic.oup.com/pmj/article/84/995/478/7026385

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17625148?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Zhao W-Y, Luo M, Sun YW, et al. Computed tomography in diagnosing vascular invasion in pancreatic and periampullary cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009 Oct;8(5):457-64.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19822487?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Catalano C, Laghi A, Fraioli F, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma: the role of high-resolution multislice spiral CT in the diagnosis and assessment of resectability. Eur Radiol. 2003 Jan;13(1):149-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12541123?tool=bestpractice.com

In the UK, urgent CT scan (or ultrasound if CT is not available) is recommended for patients aged ≥60 years with weight loss and any of the following: diarrhoea, back pain, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or new-onset diabetes.[46]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Oct 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

Patients aged ≥40 years with jaundice should be referred directly for an urgent hospital appointment.[46]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Oct 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

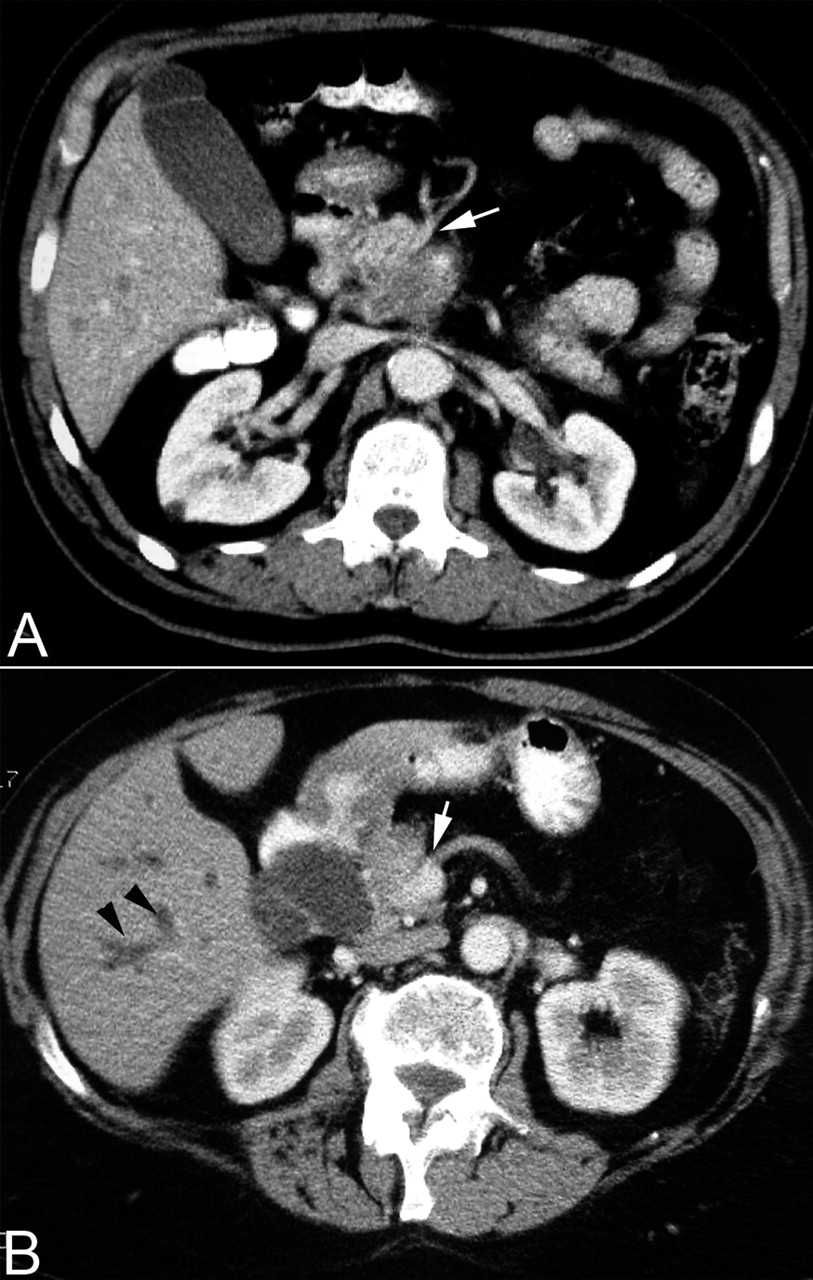

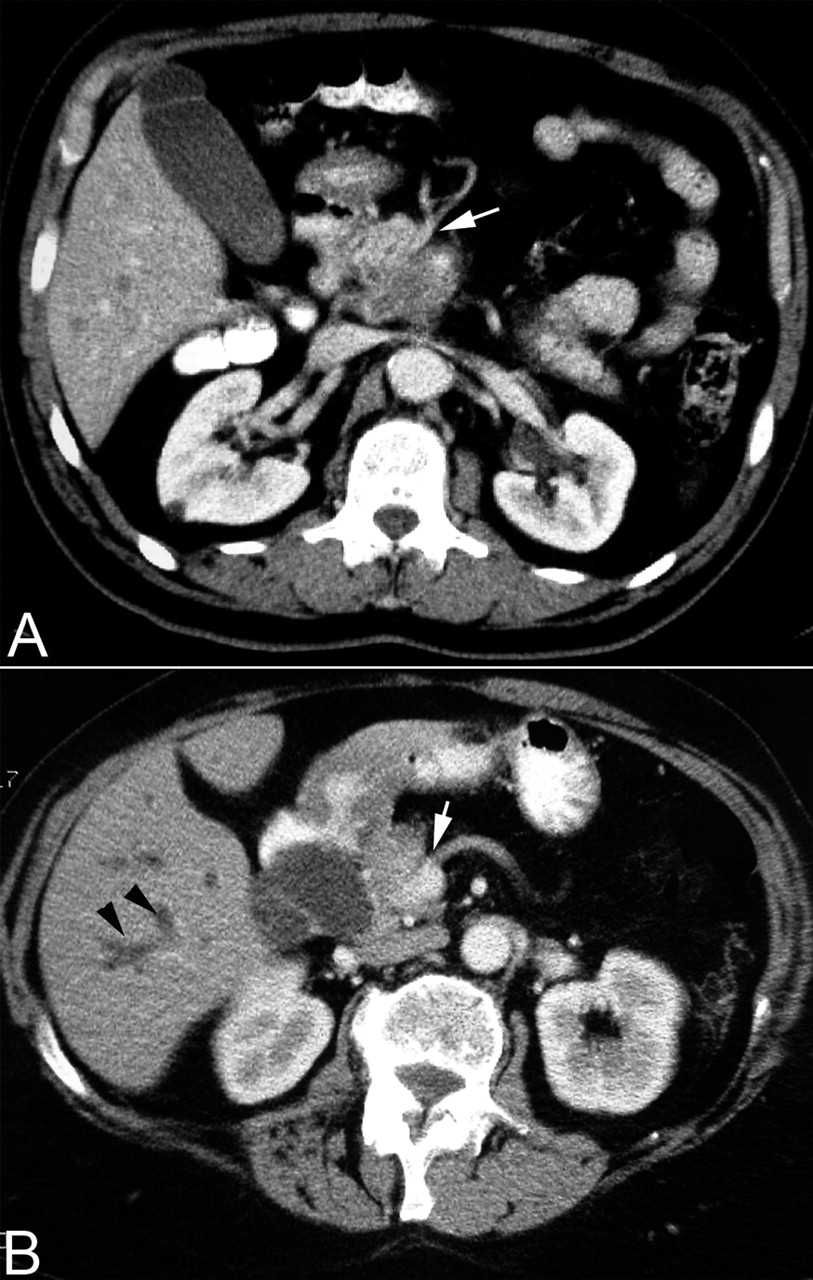

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Contrast enhanced abdominal computed tomography scan showing (A) a large mass in the head of pancreas with encasement of the superior mesenteric artery (white arrow) and (B) dilated intrahepatic ducts (black arrowheads) and encasement of the superior mesenteric vein (white arrow)Takhar AS et al. BMJ. 2004;329:668 [Citation ends].

Ultrasound

Transabdominal ultrasound may detect tumours >2 cm in size and possibly extrapancreatic spread (mainly liver metastases) or dilation of the common bile duct; the sensitivity is lower for early disease, or for tumours in the body or tail of the pancreas.[18]Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007 Aug;56(8):1134-52.

https://academic.oup.com/pmj/article/84/995/478/7026385

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17625148?tool=bestpractice.com

However, a normal abdominal ultrasound does not exclude pancreatic cancer, because the pancreas may not be adequately assessed by this modality. Overlying bowel gas or body habitus may impair visualisation of the pancreas.[47]Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging; Qayyum A, Tamm EP, Kamel IR, Allen PJ, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria® staging of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017 Nov;14(11S):S560-9.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(17)31109-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29101993?tool=bestpractice.com

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) produces similar results to CT and may be useful in patients who cannot receive intravenous contrast. MRI liver can be used to clarify ambiguous liver lesions, especially in the presence of biliary obstructions.[41]Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, et al. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023 Nov;34(11):987-1002.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(23)00824-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37678671?tool=bestpractice.com

Diffusion-weighted (DW) MRI has shown a high specificity (91%) in differentiating pancreatic lesions, and could be considered as a useful test to differentiate malignant from benign pancreatic lesions, especially when used in combination with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, which has a sensitivity of 87% to 90%. However, more studies are needed to establish the precise role of DW-MRI and PET/CT in diagnosing pancreatic cancer.[48]Wu LM, Hu JN, Hua J, et al. Diagnostic value of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging compared with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for pancreatic malignancy: a meta-analysis using a hierarchical regression model. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jun;27(6):1027-35.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07112.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22414092?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Wu LM, Xu JR, Hua J, et al. Value of diffusion-weighted imaging for the discrimination of pancreatic lesions: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Feb;24(2):134-42.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22241215?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Tang S, Huang G, Liu J, et al. Usefulness of 18F-FDG PET, combined FDG-PET/CT and EUS in diagnosing primary pancreatic carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2011 Apr;78(1):142-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19854016?tool=bestpractice.com

Positron emission tomography/CT

CT scan combined with a positron emission tomography (PET) scan may be used as an adjunct to pancreatic protocol CT to assist detection of extrapancreatic metastases in high-risk patients. High-risk indicators are high symptom burden, borderline resectable disease, large primary tumour, large regional lymph nodes, and markedly elevated CA 19-9.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

PET/CT sensitivity of 61% has been reported for the detection of metastatic disease.[51]Farma JM, Santillan AA, Melis M, et al. PET/CT fusion scan enhances CT staging in patients with pancreatic neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 Sep;15(9):2465-71.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18551347?tool=bestpractice.com

PET/CT or PET/MRI may be considered to detect extrapancreatic metastases in patients with high-risk disease, but they should not be used as a substitute to contrast-enhanced CT.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography/angiography

A non-invasive method for assessment of the biliary tract, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) provides detailed information of the ducts without the risks of invasive endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).[52]Tummala P, Junaidi O, Agarwal B. Imaging of pancreatic cancer: an overview. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011 Sep;2(3):168-74.

https://jgo.amegroups.org/article/view/213/html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22811847?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Adamek HE, Albert J, Breer H, et al. Pancreatic cancer detection with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a prospective controlled study. Lancet. 2000 Jul 15;356(9225):190-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10963196?tool=bestpractice.com

MRCP does not assess the ampulla as clearly as ERCP.[54]Barish MA, Yucel EK, Ferrucci JT. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. N Engl J Med. 1999 Jul 22;341(4):258-64.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10413739?tool=bestpractice.com

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) demonstrates the vascular anatomy.[55]Lopez Hänninen E, Amthauer H, Hosten N, et al. Prospective evaluation of pancreatic tumors: accuracy of MR imaging with MR cholangiopancreatography and MR angiography. Radiology. 2002 Jul;224(1):34-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12091659?tool=bestpractice.com

European Society for Medical Oncology recommends imaging evaluation 4 weeks prior to treatment initiation.[41]Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, et al. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023 Nov;34(11):987-1002.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(23)00824-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37678671?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with jaundice due to obstructive head pancreatic cancer, imaging should be performed before biliary drainage or stent placement.[41]Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, et al. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023 Nov;34(11):987-1002.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(23)00824-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37678671?tool=bestpractice.com

Invasive imaging

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is highly sensitive in detecting small tumours (as small as 2-3 mm) and the invasion of major vascular structures (although it is less accurate in imaging the superior mesenteric artery) and in characterising pancreatic cystic lesions.[56]Dewitt J, Devereaux BM, Lehman GA, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography for the preoperative evaluation of pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jun;4(6):717-25.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16675307?tool=bestpractice.com

EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for cytology has a sensitivity of 85% to 91% and a specificity of 94% to 98% for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.[57]Hewitt MJ, McPhail MJ, Possamai L, et al. EUS-guided FNA for diagnosis of solid pancreatic neoplasms: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Feb;75(2):319-31.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22248600?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Ngamruengphong S, Swanson KM, Shah ND, et al. Preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration does not impair survival of patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2015 Jul;64(7):1105-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25575893?tool=bestpractice.com

Fine needle aspiration of perivascular soft tissue cuffs can detect extravascular migratory metastases that are not visible on CT or MRI.[59]Rustagi T, Gleeson FC, Chari ST, et al. Safety, diagnostic accuracy, and effects of endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration on detection of extravascular migratory metastases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Nov;17(12):2533-40.e1.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.043

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30953754?tool=bestpractice.com

Risks of EUS-FNA include perforation, infection, iatrogenic pancreatitis, bleeding, bile peritonitis, and malignant seeding.[60]ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Forbes N, Coelho-Prabhu N, et al. Adverse events associated with EUS and EUS-guided procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Jan;95(1):16-26.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34711402?tool=bestpractice.com

ERCP facilitates sample collection for cytology or histology and stent placement to palliate biliary obstruction when surgery is not elected or must be delayed.[18]Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007 Aug;56(8):1134-52.

https://academic.oup.com/pmj/article/84/995/478/7026385

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17625148?tool=bestpractice.com

ERCP should not be used solely for imaging.[18]Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007 Aug;56(8):1134-52.

https://academic.oup.com/pmj/article/84/995/478/7026385

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17625148?tool=bestpractice.com

Laparoscopy, including laparoscopic ultrasound and peritoneal washes, can detect occult metastatic lesions in the liver and peritoneal cavity not identified by other imaging modalities (especially for lesions in the body or tail of the pancreas, or in patients with a higher risk of disseminated disease: borderline resectable, large primary tumour, high CA19-9).[61]Maithel SK, Maloney S, Winston C, et al. Preoperative CA 19-9 and the yield of staging laparoscopy in patients with radiographically resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 Dec;15(12):3512-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18781364?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Hori Y; SAGES Guidelines Committee. Diagnostic laparoscopy guidelines. Surg Endosc. 2008 May;22(5):1353-83.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18389320?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Hariharan D, Constantinides VA, Froeling FE, et al. The role of laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasound in the preoperative staging of pancreatico-biliary cancers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010 Oct;36(10):941-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20547445?tool=bestpractice.com

However, the selection criteria to identify patients in whom staging laparoscopy would have a high diagnostic accuracy will need to be verified in additional prospective studies.[62]Hori Y; SAGES Guidelines Committee. Diagnostic laparoscopy guidelines. Surg Endosc. 2008 May;22(5):1353-83.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18389320?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Hariharan D, Constantinides VA, Froeling FE, et al. The role of laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasound in the preoperative staging of pancreatico-biliary cancers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010 Oct;36(10):941-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20547445?tool=bestpractice.com

There is no uniform consensus regarding the use of additional staging technologies. The selective use of ERCP and/or MRCP (and occasionally MRA) will accurately define tumour size, infiltration, and the presence of metastatic disease. EUS is particularly indicated in patients whose CT scans show no lesion or who have questionable vascular or lymph node involvement. Depending on a centre's expertise, laparoscopic staging may be appropriate in some patients.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[64]Ta R, O'Connor DB, Sulistijo A, et al. The role of staging laparoscopy in resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Surg. 2019;36(3):251-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29649825?tool=bestpractice.com

Tissue diagnosis

Diagnosis by histology is not required before surgical resection; a non-diagnostic biopsy should not delay appropriate surgical treatment when clinical suspicion of pancreatic cancer is high.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

By contrast, in patients with advanced, unresectable disease selected for palliative therapy, biopsy confirmation is required.[65]Hartwig W, Schneider L, Diener MK, et al. Preoperative tissue diagnosis for tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2009 Jan;96(1):5-20.

https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/96/1/5/6141918

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19016272?tool=bestpractice.com

All patients should be referred to a centre with expertise in dealing with pancreatic diseases, without waiting for biopsy.

Guided biopsy or fine needle aspiration under EUS, or pancreatic ductal brushings, or biopsies at ERCP are preferable to a transperitoneal approach taken transcutaneously under ultrasound or CT guidance in patients with non-metastatic disease.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

The two main concerns of transperitoneal techniques are the risk of a false-negative result and tumour cells spreading along the needle track or within the peritoneum.[66]Micames C, Jowell PS, White R, et al. Lower frequency of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed by EUS-guided FNA vs. percutaneous FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003 Nov;58(5):690-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14595302?tool=bestpractice.com

Biopsy proof of malignancy is not required before surgical resection, and a non-diagnostic biopsy should not delay resection if the clinical suspicion for pancreatic cancer is high.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Metastatic disease should ideally be confirmed by core biopsy from a metastatic site.[1]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: pancreatic adenocarcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Genomic testing

Testing for actionable genomic mutations is recommended, if available, in selected patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Results are used to select the most suitable second-line treatment. Germline and tumour testing are recommended. Genomic alterations of interest include microsatellite instability/mismatch repair deficiency, BRCA mutations, and NRTK gene fusions.[43]Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Cinar P, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Aug 5:JCO2001364.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.20.01364?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32755482?tool=bestpractice.com