Alpha-thalassaemia should be suspected in patients with the appropriate ethnic background and with microcytosis without evidence for iron deficiency, with or without accompanying anaemia. Clinical manifestations are widely variable, from asymptomatic to, rarely, transfusion dependence.

Initial evaluation should focus on history and physical examination; initial laboratory testing should include a full blood count with red cell indices, reticulocyte count, and careful review of the peripheral blood smear.[3]Vichinsky E. Complexity of alpha thalassemia: growing health problem with new approaches to screening, diagnosis, and therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Aug;1202:180-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20712791?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Patients with one or two affected alpha-globin genes are likely to be asymptomatic.

Patients with haemoglobin H (Hb H) disease are variably symptomatic. In a study in patients with Hb H from Hong Kong, only 24% of those with deletional Hb H presented with symptoms, compared with 40% of those with non-deletional Hb H disease.[5]Chen FE, Ooi C, Ha SY, et al. Genetic and clinical features of hemoglobin H disease in Chinese patients. N Engl J Med. 2000 Aug 24;343(8):544-50.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200008243430804

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10954762?tool=bestpractice.com

History should include the following:

Presence and duration of symptoms related to anaemia (fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness)

Presence and duration of symptoms related to jaundice (yellow discoloration of the sclerae, skin, and mucous membranes)

Presence and duration of symptoms related to gallstones (nausea, wind, bloating, and abdominal pain)

Prior history of iron supplementation or red cell transfusion (although most patients with Hb H disease do not require chronic transfusions, in one study up to one third of those with non-deletional Hb H did require regular transfusions)[8]Vichinsky EP, MacKlin EA, Waye JS, et al. Changes in the epidemiology of thalassemia in North America: a new minority disease. Pediatrics. 2005 Dec;116(6):e818-25.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16291734?tool=bestpractice.com

Ethnic origin of the patient (sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, South Asia, and South-east Asia)

History of other affected family members

Age of the patient (because alpha-thalassaemia can have such wide variability in clinical manifestations, patients may present anywhere from in utero, with hydrops fetalis, to any point during adulthood, with an asymptomatic microcytosis; however, those with more severe manifestations will generally present in childhood or young adulthood).

Physical examination

Physical examination may be normal. In Hb H disease, jaundice may be present, splenomegaly is a common finding, and hepatomegaly may also be seen.[5]Chen FE, Ooi C, Ha SY, et al. Genetic and clinical features of hemoglobin H disease in Chinese patients. N Engl J Med. 2000 Aug 24;343(8):544-50.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200008243430804

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10954762?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Chui DH, Fucharoen S, Chan V. Hemoglobin H disease: not necessarily a benign disorder. Blood. 2003 Feb 1;101(3):791-800.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/101/3/791/88824/Hemoglobin-H-disease-not-necessarily-a-benign

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12393486?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical features of anaemia may be present with symptoms including fatigue, dizziness, and shortness of breath. Symptoms of gallstones (bloating, abdominal pain, wind) may be present.

Skeletal changes due to expansion of the erythroid bone marrow may occur, with low bone mass reported in some patients.[44]Wiromrat P, Rattanathongkom A, Laoaroon N, et al. Bone mineral density and Dickkopf-1 in adolescents with non-deletional hemoglobin H disease. J Clin Densitom. 2023 Apr 26;101379.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37147222?tool=bestpractice.com

Rarely, bone changes may lead to a milder presentation of the facial dysmorphism that is seen in sub-optimally treated beta-thalassaemia major, with maxillary hypertrophy, frontal bossing, and prominence of malar eminences.[43]Chui DH, Fucharoen S, Chan V. Hemoglobin H disease: not necessarily a benign disorder. Blood. 2003 Feb 1;101(3):791-800.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/101/3/791/88824/Hemoglobin-H-disease-not-necessarily-a-benign

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12393486?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Laosombat V, Viprakasit V, Chotsampancharoen T, et al. Clinical features and molecular analysis in Thai patients with HbH disease. Ann Hematol. 2009 Dec;88(12):1185-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19390853?tool=bestpractice.com

Growth retardation may also be seen in children.[5]Chen FE, Ooi C, Ha SY, et al. Genetic and clinical features of hemoglobin H disease in Chinese patients. N Engl J Med. 2000 Aug 24;343(8):544-50.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200008243430804

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10954762?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Laosombat V, Viprakasit V, Chotsampancharoen T, et al. Clinical features and molecular analysis in Thai patients with HbH disease. Ann Hematol. 2009 Dec;88(12):1185-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19390853?tool=bestpractice.com

Extramedullary haematopoiesis leading to paraspinal masses has been described.[46]Wu JH, Shih LY, Kuo TT, et al. Intrathoracic extramedullary hematopoietic tumor in hemoglobin H disease. Am J Hematol. 1992 Dec;41(4):285-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1288291?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Benz EJ Jr, Wu CC, Sohani AR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 25-2011. A 62-year-old woman with anemia and paraspinal masses. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 18;365(7):648-58.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21848466?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial laboratory evaluation

The initial laboratory evaluation should include a full blood count, reticulocyte count, haemolytic tests, and red cell indices, including measurement of the mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH), and red blood cell count.[16]Thalassaemia International Federation. Guidelines for the management of alpha-thalassaemia. 2023. If microcytosis (MCV <78 femtolitres) or hypochromia (MCH <27 picograms/cell) is present, iron status should be assessed (serum iron, transferrin, transferrin saturation, and ferritin) to consider iron-deficiency anaemia as the differential diagnosis. If iron studies are ambiguous or borderline, a short, well-monitored trial of iron supplementation may be warranted to rule out iron-deficiency anaemia.

In Hb H disease, the reticulocyte percentage is elevated (5% to 10%) and may be further increased during acute infections or haemolytic crises.[48]Thalassaemia International Federation. A short guide for the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia. 2nd ed. 2022 [internet publication].

https://thalassaemia.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TDT-GUIDE-2022-FOR-web.pdf

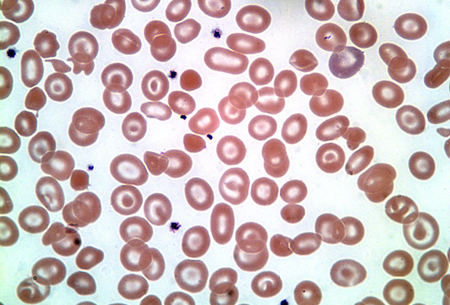

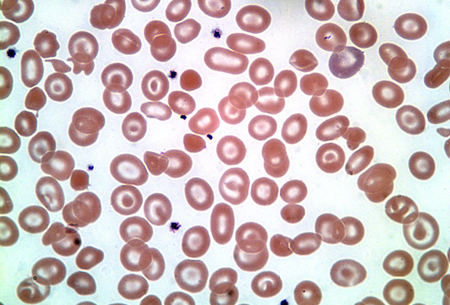

The peripheral smear should be carefully reviewed for findings consistent with alpha-thalassaemia, including microcytosis, hypochromia, increased polychromasia, target cells, and anisopoikilocytosis.[48]Thalassaemia International Federation. A short guide for the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia. 2nd ed. 2022 [internet publication].

https://thalassaemia.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TDT-GUIDE-2022-FOR-web.pdf

Mis-shapen and even fragmented red cells may be found in patients with Hb H disease, and characteristic inclusion bodies may be seen on staining with a supravital dye such as brilliant cresyl blue.[16]Thalassaemia International Federation. Guidelines for the management of alpha-thalassaemia. 2023. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Haemoglobin H diseaseFrom the collection of Elizabeth A. Price and Stanley L. Schrier, Stanford University [Citation ends].

In homozygous Hb Constant Spring, the cells will be normal or slightly small in size, and basophilic stippling may be prominent.[6]Pootrakul P, Winichagoon P, Fucharoen S, et al. Homozygous haemoglobin Constant Spring: a need for revision of concept. Hum Genet. 1981;59(3):250-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7327587?tool=bestpractice.com

Subsequent laboratory evaluation

Hb H and Hb Bart can be detected as fast-moving haemoglobins. Hb H is not always reliably detectable by routine Hb electrophoresis, and some experts feel that Hb H inclusion bodies are more reliable for the diagnosis of Hb H disease.[4]Harteveld CL, Higgs DR. Alpha-thalassemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010 May 28;5:13.

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1750-1172-5-13

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20507641?tool=bestpractice.com

Hb fractionation and automatic measurement can also be performed with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).[4]Harteveld CL, Higgs DR. Alpha-thalassemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010 May 28;5:13.

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1750-1172-5-13

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20507641?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Thalassaemia International Federation. Guidelines for the management of alpha-thalassaemia. 2023. These testing modalities will also putatively identify all common haemoglobin disorders (i.e., Hb E, Hb S, Hb C, Hb D), which may be present and impact on the clinical course. Hb electrophoresis and HPLC will not, however, detect deletions or mutations in only one or two alpha-globin genes, neither will they differentiate deletional versus non-deletional Hb H disease (except for Hb Constant Spring).

Characterisation of alpha-thalassaemia

Always requires DNA-based alpha-globin gene testing. Seven of the most common alpha-thalassaemia deletions (-alpha(3.7), -alpha(4.2), --(FIL), --(THAI), --(MED), -(alpha)(20.5), --(SEA)) can be diagnosed by gap-polymerase chain reaction (gap-PCR).[48]Thalassaemia International Federation. A short guide for the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia. 2nd ed. 2022 [internet publication].

https://thalassaemia.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TDT-GUIDE-2022-FOR-web.pdf

Other deletion alleles are detected by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification.[48]Thalassaemia International Federation. A short guide for the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia. 2nd ed. 2022 [internet publication].

https://thalassaemia.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TDT-GUIDE-2022-FOR-web.pdf

Non-deletional alpha-thalassaemia mutations are usually detected by direct sequencing or reverse dot blot.[48]Thalassaemia International Federation. A short guide for the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia. 2nd ed. 2022 [internet publication].

https://thalassaemia.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TDT-GUIDE-2022-FOR-web.pdf

[49]Sabath DE. Molecular diagnosis of thalassemias and hemoglobinopathies: an ACLPS critical review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2017 Jul 1;148(1):6-15.

https://academic.oup.com/ajcp/article/148/1/6/3866692

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28605432?tool=bestpractice.com

There is no simple approach to detect all known mutations. Reference laboratories with expertise in diagnosis of haemoglobinopathies may be needed to diagnose difficult cases in a timely manner, particularly for genetic counselling purposes.

Iron overload

If iron status is significantly elevated as evident by a serum ferritin >1797.6 picomol/L (>800 nanograms/mL), hepatic iron overload should be assessed by R2 or R2* magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUID), or liver biopsy (less preferred).[16]Thalassaemia International Federation. Guidelines for the management of alpha-thalassaemia. 2023.[48]Thalassaemia International Federation. A short guide for the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia. 2nd ed. 2022 [internet publication].

https://thalassaemia.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TDT-GUIDE-2022-FOR-web.pdf

[50]Northern California Comprehensive Thalassemia Center. Standards of care guidelines for thalassemia. 2012 [internet publication].

https://thalassemia.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra7596/f/SOC-Guidelines-2012.pdf

[51]Wood JC. Diagnosis and management of transfusion iron overload: the role of imaging. Am J Hematol. 2007 Dec;82(suppl 12):1132-5.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ajh.21099

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17963249?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum ferritin levels may underestimate liver iron concentration.[52]Lal A, Goldrich ML, Haines DA, et al. Heterogeneity of hemoglobin H disease in childhood. N Engl J Med. 2011 Feb 24;364(8):710-8.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1010174

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21345100?tool=bestpractice.com

Cardiac iron loading is assessed by T2* cardiac MRI.[48]Thalassaemia International Federation. A short guide for the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia. 2nd ed. 2022 [internet publication].

https://thalassaemia.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TDT-GUIDE-2022-FOR-web.pdf

Cardiac iron loading is uncommon in non-transfused patients.