Approach

Historical and examination findings often narrow the differential diagnosis considerably. The initial tests to order in a patient presenting with hypocalcaemia are serum total calcium concentration, albumin, magnesium, renal function, and serum intact parathyroid hormone level.[1]

History

The age at which hypocalcaemia and hypocalcaemic symptoms and signs manifest is important. If hypocalcaemia occurs at an early age, congenital aetiologies should be investigated. If it occurs in an older person living in a nursing home, where there may be little access to sunshine, then vitamin D deficiency is a likely cause.

A history of neck surgery points towards possible causes of hypocalcaemia. Patients undergoing thyroidectomy may have parathyroid glands accidentally removed, damaged, or devascularised. Another cause of hypocalcaemia after surgery is 'hungry bone' syndrome, which usually occurs during the first 2 postoperative days of parathyroid adenoma surgery. These patients need massive replacement of calcium and magnesium.

Fatigue, muscle weakness, cramps, and pain may suggest vitamin D deficiency.

Abdominal pain with signs of hypocalcaemia suggests the possibility of acute pancreatitis.

Medication history could alert to iatrogenic causes of hypocalcaemia. These include the use of proton-pump inhibitors, bisphosphonates, denosumab, chemotherapy, chelating agents, glucocorticoids, anticonvulsants, or cinacalcet.[12][23][24][25][29]

Chronic complaints of numbness and tingling in the fingertips, toes, and perioral region can indicate hypocalcaemia.

Family history of hypocalcaemia should be investigated.

Patients taking immunosuppressive drugs and/or with a history of skin cancer will become vitamin D deficient if they follow rigorous sun avoidance advice. People who routinely use high SPF sunscreen, have dark skin and live in northern latitudes, wear concealing clothing, are chronically housebound, or have fat-soluble vitamin malabsorption, are at risk of severe vitamin D deficiency. Factors including male sex, abnormal body mass index, non-white ethnic background, smoking, and socioeconomic deprivation have also been associated with increased risk for vitamin D deficiency.[31]

Presence of chronic diarrhoea with steatorrhoea and intestinal disease, such as Crohn's disease or chronic pancreatitis, may suggest hypocalcaemia due to malabsorption of calcium or vitamin D.

Malnutrition or chronic illness may result in decreasing circulating albumin, which is a common cause of hypocalcaemia.

A history of repeated blood transfusions for chronic anaemia, or defects of iron metabolism (e.g., haemochromatosis) or copper metabolism (e.g., Wilson's disease), and less commonly a current malignancy, could suggest an infiltrative process in the parathyroid glands.[8][9]

Physical examination

Patients with hypocalcaemia may have no physical signs.

Trousseau's sign may be apparent. This is a carpopedal spasm in response to ischaemia that occurs when a blood pressure cuff is used for several minutes. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carpopedal spasm (Trousseau's sign) occurred a few minutes after inflation of a sphygmomanometer cuff above systolic blood pressurePedrazzini B et al. BMJ Case Reports 2010;2010:bcr.08.2009.2188 [Citation ends].

Carpopedal spasm that occurs in alkalosis (e.g., due to hyperventilation) may occur in patients with hypocalcaemia. This is a painful spasm of the hands and feet that could be a presenting sign, particularly in patients with a history of panic attacks/hyperventilation.

Arrhythmias may manifest as an irregular heart beat on exam.

Healed surgical scar at the base of the neck could indicate thyroid surgery that might have caused parathyroid gland loss or damage.

Chvostek's sign (brief contraction/twitching of perioral muscles, resulting in contraction of the corner of the mouth, ipsilateral nasal musculature, and ipsilateral eye musculature) may be elicited by tapping over cranial nerve VII at the ear. Chvostek's sign is neither sensitive nor specific for hypocalcaemia.[3]

Seizure disorder or muscle cramps related to tetany are presenting signs in patients with severe hypocalcaemia.

Kyphoscoliosis in an older patient could indicate osteoporosis secondary to chronic vitamin D deficiency or osteomalacia.

Neurological manifestations such as irritability, extrapyramidal symptoms, personality disorder, choreoathetosis, and dystonia could be signs of neurological manifestation of cerebellar or basal ganglia calcification.[32]

A short fourth metacarpal bone (brachydactyly) is an important sign of pseudohypoparathyroidism.[14]

Subcapsular cataracts can indicate chronic hypocalcaemia.[4]

Optic disc oedema can occur in severe cases of hypocalcaemia. It may or may not be associated with increased intracranial pressure.[33]

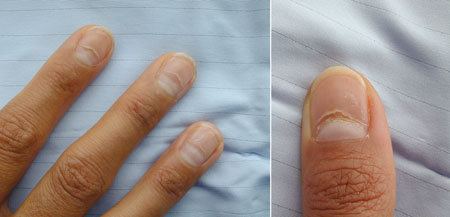

Skin is dry, coarse, and puffy in patients with chronic hypocalcaemia. Hyperpigmentation and eczema can also occur in rare cases. Nail changes may occur. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nail dystrophy due to hypocalcaemiaNijjer S et al. BMJ Case Reports 2010;2010:bcr.08.2009.2216 [Citation ends].

Patients with congenital abnormalities may present with highly variable features, ranging from mild learning disabilities to the complete spectrum of congenital malformations (such as the classic triad of cardiac anomalies, hypoplastic thymus, and hypocalcaemia seen in DiGeorge syndrome) and other aspects of velopharyngeal insufficiency (e.g., cleft palate).

Laboratory evaluation

Initial tests include serum total calcium concentration, albumin, and magnesium; renal function; and serum intact parathyroid hormone level.

Other investigations commonly include serum levels of ionised calcium, bicarbonate, alkaline phosphatase, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D; and 24-hour urine calcium and creatinine.[34]

Serum total calcium levels, adjusted for albumin, should be the first test performed in patients presenting with symptoms and signs of hypocalcaemia.

Serum albumin concentration should be tested, as over 40% of circulating calcium is bound to albumin in a ratio of 0.8 mg calcium to 1 mg albumin. This ratio is conventionally used to adjust the total calcium after measuring albumin. Using SI units (calcium mmol/L; albumin g/L), the formula for adjusted serum calcium is:

(0.02 × [normal albumin - patient’s albumin]) + serum calcium.

Using conventional units (calcium mg/dL; albumin g/dL), the formula for adjusted serum calcium is:

(0.8 × [normal albumin - patient’s albumin]) + serum calcium.

However, the formula is superseded when ionised calcium is measured (where available). The formula for adjusted calcium may not be reliable in all circumstances (such as in critically ill patients).

Serum magnesium should be measured where hypomagnesaemia is suspected. Hypomagnesaemia or severe hypermagnesaemia can cause hypocalcaemia and may indicate the underlying aetiology. Any cause of hypomagnesaemia (e.g., use of proton-pump inhibitors [PPIs]) can result in hypocalcaemia.[12][29] It is important to identify hypomagnesaemia, because calcium cannot be adequately adjusted unless magnesium has first been replaced. Hypomagnesaemia secondary to PPI use can only be adjusted by stopping the PPI.

Renal function: elevated urea and creatinine can indicate renal dysfunction.

Intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels should be tested in every patient with hypocalcaemia. PTH levels will be low in overt hypoparathyroidism (e.g., iatrogenic or infiltrative damage, congenital absence) and are raised in vitamin D deficiency, renal disease, and in malignancies with skeletal metastases.

25-hydroxyvitamin D levels should be measured in patients suspected of having vitamin D deficiency. Serum alkaline phosphatase may also be useful in these patients (where levels may be elevated). Alkaline phosphatase is raised in patients with skeletal metastases.

Serum chemistries including (ionised) calcium, bicarbonate, alkaline phosphatase, and phosphorus should be obtained: high levels of phosphate in the absence of renal failure and tissue breakdown indicate hypoparathyroidism or pseudohypoparathyroidism.

Amylase and/or lipase levels should be checked in patients with abdominal pain. In acute pancreatitis the amylase and lipase levels are significantly increased.[35] Use serum lipase testing in preference to serum amylase.[36]

Serum creatinine, creatine kinase, magnesium, and phosphorus levels are particularly relevant tests in patients suspected of having rhabdomyolysis and cell lysis syndrome.

T-cell counts are useful in suspected DiGeorge syndrome where a T-cell lymphopenia is commonly seen. Fluorescence in situ hybridisation analyses can confirm 22q11.2 deletion.

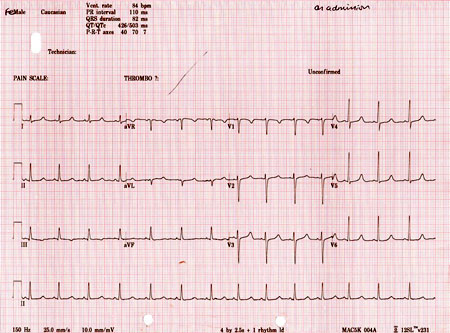

ECG should be performed to evaluate arrhythmias and prolonged QT intervals. Hypocalcaemia prolongs phase II action potential, leading to prolonged QT intervals, which may be the only electrocardiographic sign of hypocalcaemia. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Electrocardiogram (ECG) showing an adjusted QT interval (QTc) of 503 ms while in sinus rhythmNijjer S et al. BMJ Case Reports 2010;2010:bcr.08.2009.2216 [Citation ends].

Imaging studies

X-rays should be performed when multiple fractures or signs of osteomalacia are observed.

Isotope bone scans should be performed for patients with possible malignant metastasis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer