Approach

The initial decision that the clinician must address is whether or not the patient is in shock.

Patients with hypotension may present in various clinical states, ranging from critically ill with shock, to asymptomatic. A normal blood pressure (BP) does not necessarily mean normal perfusion, as adequate pressure does not equate to adequate cardiac output.[48] Therefore, thorough examination for other signs of inadequate perfusion and monitoring is important.

If BP is unrecordable and assessment finds the patient unresponsive with no palpable pulse, the clinician should proceed to resuscitation, if appropriate, in accordance with resuscitation guidelines.[30] Resuscitation Council (UK): 2021 resuscitation guidelines Opens in new window

When there is no evidence of shock, the clinician must assess if the hypotension is an acute change from previous status and if there is clinical evidence of a precipitating event (e.g., myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal bleed, pulmonary embolism). If the presentation is chronic or recurring, a chronic illness that may explain the patient's hypotension should be identified.

The patient's risk of falling should be assessed by a multi-disciplinary team (nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy). This is particularly important in patients known to have a chronic illness predisposing them to hypotension, such as diabetes mellitus, Addison's disease, or parkinsonism.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Summary of assessment in a hypotensive adultCreated by The BMJ Group [Citation ends].

Blood pressure measurement

Hypotension is defined as any BP that is below the normal expected for an individual in a given environment. There is no single numerical cut-off universally accepted as representing hypotension. It is essential to use an appropriate cuff size for BP measurements. Using a cuff that is too small (under-cuffing) may cause overestimation of BP and may further mask a period of hypotension; while use of a cuff that is too large (over-cuffing) can lead to falsely low BP readings with subsequent unwarranted investigation.[3] The patient should be seated comfortably for five minutes before BP measurement. The BP cuff should be at the level of the heart, with the lower edge of the cuff a few centimetres above the antecubital fossa. The patient’s arm and back should be supported, and legs unfolded.[5]

It is helpful to know previous BP measurements for comparison.

If the patient is not hypotensive at the time of assessment, lying and standing BP recordings should be carried out in order to determine if orthostatic hypotension is present. The patient should rest supine for 5 minutes before lying BP measurement.[4] A systolic BP drop of 20 mmHg, or a diastolic BP drop of 10 mmHg occurring within 3 minutes of orthostasis is considered significant.[5][6]

Most automatic sphygmomanometers overestimate blood pressure in patients with atrial fibrillation, because they record the highest systolic pressure rather than an average over several cardiac cycles. Palpate the patient’s pulse to exclude arrhythmia before using an automatic sphygmomanometer.[5]

Determining the presence of shock

Patients are acutely ill and require urgent life-saving intervention.

History should be a brief assessment, concurrent with airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC) resuscitation and supportive care. Establishing if the patient is alert and orientated by asking some general questions to assess their cognition is a reasonable first step. If the patient is unresponsive and hypotensive, the presence of shock should be assumed until proven otherwise.

Pointers towards specific causes include:

early pregnancy (may be ruptured ectopic pregnancy)

cardiac disease (may be cardiogenic shock due to various causes)

chronic liver disease (gastrointestinal bleed)

exposure to a known allergen (anaphylaxis)

risk factors for thrombosis (PE)

recent infection or known immunodeficiency (sepsis)

trauma (haemorrhage due to long bone fracture or other injuries)

presence of aortic aneurysm

endocrine disorder (Addisonian crisis, severe hypothyroidism).

Accurate recording of vital signs (heart rate, BP, urine output, temperature) and determination of level of consciousness is essential.

Tachycardia, altered cognition or reduced level of consciousness, diaphoresis and oliguria are all pointers to the presence of shock. Indicators of regional perfusion (e.g., urine output, change in mental status, and respiratory rate) are important because early haemodynamic assessment based on vital signs and central venous pressure (CVP) may fail to detect persistent global hypoxia.[49]

General inspection should include assessment of whether or not the patient appears clammy, or whether their peripheries are warm. If possible, a quick review of systems should be completed so that any precipitant present can be identified. Specific signs indicating the precipitating cause include:

Dry mucous membranes, lack of axillary moisture, decreased skin turgor, diarrhoea, vomiting, rigorous exercise, exposure to prolonged or excessive heat (dehydration).

Acute haemorrhage, externally apparent (some types of trauma).

Suspected haemorrhage: gastrointestinal bleeding (abdominal tenderness, pallor, melaena or fresh bleeding on rectal examination), ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (abdominal tenderness, presence of abdominal pulsatile mass, gradual loss of consciousness and weak peripheral pulses), retroperitoneal bleed (abdominal tenderness, possible bruising in the flanks), ruptured ectopic pregnancy (abdominal tenderness and guarding, decreased bowel sounds, cervical motion tenderness, and vaginal bleeding in the presence of a positive pregnancy test).

Diaphoretic appearance, pallor, tachycardia, bradycardia, or new abnormal pulse rhythm, distended jugular veins, dyspnoea, crackles at lung bases, and new heart murmur may occur in cardiogenic shock (e.g., due to acute coronary syndrome or acute heart failure). Pulse may be abnormal in patients with acute cardiac dysrhythmias.

Distended jugular veins, reduced heart sounds and hypotension (Beck's triad), along with increased respiratory rate, tachycardia, and pulsus paradoxus indicate cardiac tamponade.

Cyanosis, profuse diaphoresis, absent unilateral breath sounds, hyper-resonance to percussion over one lung, tracheal shift from midline are classic signs of a tension pneumothorax.

Tachypnoea, pleural rub on chest auscultation, low oxygen saturations, and possible calf tenderness may be present in the case of a large acute PE.

Elevated or low temperature, altered mental status, with or without focal signs of infection, occur with sepsis. However, sepsis should be considered if a patient presents with signs or symptoms that indicate possible infection, regardless of temperature.[37] Sepsis may present initially with non-specific, non-localised symptoms, such as feeling unwell with normal temperature.

Bronchospasm, rash, angio-oedema of the tongue, lips, or eyelids, flushing; rhinitis, inspiratory stridor, syncope are signs in anaphylaxis.

Sudden collapse due to Addisonian crisis may be difficult to diagnose unless suspected from the history and typical patient features (e.g., hyperpigmentation). Adrenal suppression should be considered in patients taking chronic glucocorticoids who have not received stress doses of steroids during an intercurrent illness or who have had chronic steroids abruptly withdrawn.

Severe hypothyroidism may progress to signs of cardiogenic shock and coma. There may be hypothermia, bradycardia, and signs of chronic hypothyroid disease including coarse hair, facial oedema, eyelid oedema, and thick tongue.

Determining the type of shock

Unless immediately clear, it may be necessary to determine the relative contributions of volume depletion, reduced cardiac pump function, and impaired peripheral vasoconstriction in order to select the most appropriate treatment interventions.

First assess whether the patient responds to fluids. A good response indicates a decreased preload.

Fluid responsiveness can be assessed by:

Passive leg raising:

The patient's legs are raised to 45 degrees. The transfer of blood from the legs and abdomen increases venous return. An increase in cardiac output of 10% or more is considered a positive test. A positive passive leg raise test has a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 91% for fluid challenge responsiveness.[50]

Bolus of intravenous fluids:

Helps determine if the patient has a decreased preload. Typically, an increase in stroke volume of 10% to 12%, with a fluid bolus of 300 mL to 500 mL of crystalloids, is taken as a positive response.[51]

Ultrasonography:

The SHoC (Sonography in Hypotension and Cardiac arrest) consensus statement outlines a recommended point-of-care ultrasound protocol to help identify a cause of hypotension. This includes: cardiac views to assess for pericardial fluid, ventricle size, shape and contractility, valve opening and signs of right heart strain; lung views to look for pulmonary oedema, consolidation, pneumothorax and pleural fluid; and inferior vena cava (IVC) views to assess diameter and variation in size with respiration. A large diameter IVC with little variability indicates high right heart filling pressures, while a small diameter IVC with more respiratory variation indicates hypovolaemia which could respond to fluid resuscitation.[52] However, a more recent randomised controlled trial did not identify a survival benefit for point-of-care ultrasonography for undifferentiated hypotension in the emergency department.[53] The most common diagnosis, in more than half of the patients, was occult sepsis.

Echocardiography:

Provides information on pulmonary artery pressure. More readily available and less invasive than pulmonary artery catheterisation.

Pulmonary artery catheterisation:

insertion allows for measurement of pulmonary artery occlusion pressure and is the test of choice for assessment and monitoring. A range of 12 to 18 mmHg is associated with adequate filling. It is variably affected by the presence of many conditions (e.g., mechanical ventilation, use of positive end expiratory pressure ventilation, increased abdominal pressure, decreased left ventricular function, or pericardial compliance). A pulmonary artery catheter is particularly useful in cardiogenic shock as it provides a route for direct measurement of cardiac output. Cardiogenic shock is suggested by an elevated pulmonary artery occlusion pressure with levels >18 mmHg to 20 mmHg and low preload states are usually associated with reduced pulmonary artery occlusion pressure levels of <10 mmHg.

If the patient is fluid responsive, assess whether the arterial tone (afterload) is increased or decreased and whether pump function (cardiac contractility) is increased or decreased.

Measures for assessment include:

Cardiac output (CO) can be calculated in various ways (e.g., by dilution and thermodilution using a pulmonary artery catheter, Doppler ultrasound, and measurements of pulse pressure).

Pulse pressure is the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Pulse pressure is narrow when it is <25% of systolic pressure. Narrowed pulse pressure may indicate decreased cardiac output due to decreased circulating volume, acute heart failure or cardiac tamponade. In patients with a penetrating traumatic injury, narrowed pulse pressure is associated with the presence of haemorrhagic shock, need for massive transfusion and need for emergent surgery.[54]

The cardiac index is helpful in quantifying the relative contributions of impaired peripheral vasoconstriction and reduced cardiac pump function to shock. The cardiac index is the ratio of the CO to body surface area in metres squared with normal values ranging between 2.5 to 4.0 L/min/m². In cardiogenic shock, the cardiac index is typically <1.8 L/min/m² without inotropes, and <2.0 to 2.2 L/min/m² with inotropes.[55]

Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) can be calculated as a measure of afterload as follows: SVR = mean arterial pressure - CVP/CO × 80. The ratio to the body surface area is called the SVR Index and ranges from 1800 to 2800.

There are various indicators of the level of tissue perfusion, including serum lactate levels. Levels ≥4 mmol/L are associated with greater mortality in shock. Base excess levels can be misleading and are generally not used.

Acute hypotension without shock

The history should include:

A general enquiry about the presence of fever/chills should be made (sepsis).

Cardiovascular history should concentrate on the presence or absence of chest pain (myocardial infarction, PE), palpitations (dysrhythmia) and dyspnoea (acute heart failure, PE).

Respiratory history should concentrate on the presence of dyspnoea (PE, acute heart failure), haemoptysis (PE, pneumonia/sepsis or acute heart failure), and pleuritic pain (PE, pneumonia/sepsis).

Abdominal/gastrointestinal history should focus on the presence of abdominal pain (peptic ulcer disease causing gastrointestinal bleed, abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture, or diverticular disease causing lower gastrointestinal bleed), haematemesis (upper gastrointestinal bleed), haematochezia, and symptoms of vomiting and diarrhoea (gastroenteritis).

Genitourinary history should include a search for symptoms of urosepsis and haematuria.

Of note, many of the common precipitants of acute hypotension present atypically in older adults.[1] Examples of such illnesses include myocardial infarction, peptic ulcer disease, PE, and pneumothorax.[2][29][56][57]

The presence of a previous stroke predisposing to hypotension is usually apparent from the patient's recent history as hypotension post-stroke typically occurs in the first few days following acute stroke.

Past medical history

The patient's past medical history should be noted in order to determine if he or she has any condition that may predispose the patient to acute hypotension (e.g., known peptic ulcer disease, ischaemic heart disease, chronic liver disease, diabetes mellitus, previous deep vein thrombosis or PE).

If the patient is dependent on renal replacement therapy (dialysis), the presence of dialysis-induced hypotension should be considered. A meta-analysis found that the incidence of dialysis-induced hypotension is 12%. Diabetes, large interdialytic weight gain, female sex and low body weight are risk factors for dialysis-induced hypotension.[58]

Medication history

Medication-related hypotension is the most common cause of acute hypotension with no previous history of hypotensive events, particularly in older patients.[59] Cardiovascular medications, older antidepressants, and psychotropics are most commonly implicated.[60] Medication may be one of several interacting factors in older patients (e.g., anti-hypertensive and/or vasodilatory medication, dehydration, and illness-associated impaired vasoconstriction). Administration of intravenous paracetamol can cause a drop in blood pressure in critically ill hospitalised patients.[61] Temporary suspension of implicated medication with gradual re-introduction is often required. In the longer term, removal of medication must be considered individually for each patient, and must be weighed against the potential benefits of specific agents. Taking an accurate medication history is also important because some medications increase the risk of certain differentials (e.g., younger women taking the oral contraceptive pill have a higher risk for PE).

The presence of any previously recorded allergy or episodes of anaphylaxis should be noted.

Social history

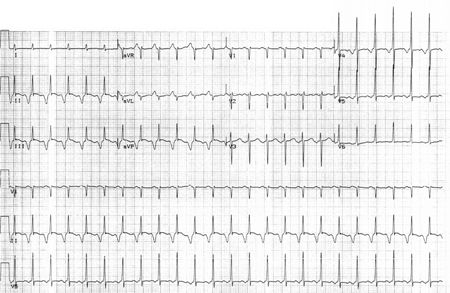

The patient's social history should include details of smoking (peptic ulcer disease, PE, myocardial infarction), alcohol use (peptic ulcer disease, chronic liver disease), or any illegal drug use (e.g., cocaine usage predisposes to dysrhythmias and acute coronary syndromes).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG demonstrating episode of paroxysmal atrial tachycardia in a 35-year-old with history of recent cocaine useFrom the collection of Sarah Stahmer, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; used with permission [Citation ends].

Examination

General inspection should include assessment of whether the patient appears comfortable at rest, or appears to be distressed (e.g., tension pneumothorax). A raised respiratory rate may be a pointer to the presence of an acute cardiac or respiratory problem (e.g., acute heart failure) but can also be present if the patient is acidotic (e.g., sepsis).

Head and neck examination should note the presence of jaundice (chronic liver disease/gastrointestinal bleed/sepsis), cyanosis (acute heart failure), trachea position (displaced by tension pneumothorax), distended jugular veins (acute heart failure, tamponade).

Consideration of the patient's volume status/hydration may be made by examining skin turgor and mucous membranes. The presence of any signs of chronic liver disease may be a pointer to the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding or sepsis. Evidence of cellulitis (sepsis) should be excluded on examination of the upper and lower limbs. Increased pigmentation is a sign frequently noted in patients with Addison's disease and chronic renal failure.

Cardiovascular examination should include assessment of the volume of heart sounds (muffled/reduced in cardiac tamponade, often loud if tachycardia present due to sepsis), the presence of any new murmur (acute heart failure due to cardiac valvular dysfunction, as may occur post-myocardial infarction, or with endocarditis), and the presence of additional heart sounds (heart failure). Patients with right heart failure may present with compartmental dehydration; i.e., present with ankle oedema but have simultaneous intravascular depletion.

Respiratory examination may reveal crackles at the lung base (acute heart failure), absent or reduced air entry with hyper-resonant note to percussion (pneumothorax), or consolidation signs (pneumonia/sepsis). Bi-basal crackles may be a manifestation of chronic lung disease. Occasionally, a pleural rub may be heard to indicate the presence of a PE although a normal respiratory examination does not exclude the presence of one.

Abdominal examination should include evaluation of upper abdominal tenderness (peptic ulcer disease/upper gastrointestinal bleed), a check for the presence of a pulsatile mass (abdominal aortic aneurysm), left lower quadrant tenderness (lower gastrointestinal bleed), and assessment of any signs that may indicate the presence of chronic liver disease (caput medusae, telangiectasia, splenomegaly). If a pulsatile mass is felt, it is important to check for reduced femoral pulses that are suggestive of bleeding abdominal aortic aneurysm. A rectal examination should be performed if gastrointestinal bleeding is suspected.

Focal neurological signs may be present if hypotension is occurring post-stroke. In many cases this may result from injudicious introduction of anti-hypertensive medication. The patient should be kept supine for 24 hours and any hypotension predisposing medication withheld.

Investigations

The following investigations should be performed in all patients with acute hypotension, including patients with shock, where the diagnosis may not be clear:

FBC (a low haemoglobin may or may not be present with haemorrhage, an elevated WBC count may be indicative of infection or inflammation)

Serum electrolytes and blood glucose

Serum liver transaminases and bilirubin

Serum troponin

D-dimer (may be normal or elevated with PE)

Coagulation profile

12-lead ECG (may be followed by cardiac telemetry, and 24-hour ECG in patients with suspected dysrhythmia)

Pulse oximetry recording

Thyroid function tests (thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH] and free T4) may also be considered in older adults.

Further investigations are directed towards identifying the cause of the hypotension and monitoring the patient’s response to initial treatment. Investigations may include:

Arterial blood gas measurements may be useful in patients with sepsis, suspected dehydration, and PE.

Serum lactate measurements to monitor response to resuscitation in septic shock.

In all cases where bleeding is suspected, sending a blood sample for group and save is prudent.

Pregnancy testing is valuable and may help to confirm a pregnancy-related cause such as ectopic pregnancy.

Inflammatory markers may be raised in sepsis or an inflammatory cause of cardiac tamponade.

Microbiological cultures from the site of suspected sepsis, e.g., mid-stream urine culture, lumbar puncture, sputum culture and blood cultures.

Chest x-ray: may demonstrate pneumonia as a source of sepsis. Performed in cases of suspected PE (although frequently normal), cardiac tamponade, acute coronary syndrome and acute heart failure. Chest x-ray should also be performed after, but not before, emergency chest decompression for tension pneumothorax.

Echocardiogram: may be performed in cases of acute heart failure, cardiac tamponade, sepsis and acute coronary syndrome.

Coronary angiogram may be performed in people with acute coronary syndrome.

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) may help to confirm suspected acute heart failure. In acute settings, levels of natriuretic peptide biomarkers such as BNP may be more useful for ruling out than ruling in a diagnosis of heart failure.[28][62] Higher levels of natriuretic peptide biomarkers are associated with increased risk for long-term adverse outcomes (including all-cause and cardiovascular death) in patients with heart failure.[62] Several other cardiac and non-cardiac conditions may also be associated with elevated levels.[28][62]

Multi-detector computed tomography [CT] pulmonary angiography, ventilation/perfusion [V/Q] scan, transthoracic echocardiography, pulmonary angiography, and duplex ultrasound of femoral and calf veins) may be used to confirm the diagnosis of PE.

CT angiogram may confirm the diagnosis of leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm, if the patient’s condition is not critical. An abdominal CT may also be performed in patients who are stable with suspected retroperitoneal bleed.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with suspected upper gastrointestinal bleed, and colonoscopy for people with suspected lower gastrointestinal bleed, may provide the definitive diagnosis.

Following stabilisation of a patient with Addisonian crisis, the diagnosis may be further investigated with a morning serum cortisol, and a high-dose (250 micrograms) adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test.[63]

Primary hypothyroidism is diagnosed by elevated serum TSH and low T4.

Various tests may help confirm anaphylaxis and identify the allergen to which the patient has become sensitised. In adults, blood should be taken to assess mast cell tryptase levels as soon as possible after emergency treatment has started with a second sample ideally within 1 to 2 hours (but no later than 4 hours) from the onset of symptoms. A third sample should be taken during a follow-up appointment.[64] Serum histamine is a less specific marker for anaphylaxis. A radioallergosorbent test, specific skin tests (Ig E), and a post-episode challenge test may be helpful in identifying the allergen.[46][64]

How to decompress a tension pneumothorax. Demonstrates insertion of a large-bore intravenous cannula into the fourth intercostal space in an adult.

Ultrasound-guided insertion of a non-tunnelled central venous catheter (CVC) into the right internal jugular vein using the Seldinger insertion technique.

How to insert a peripheral venous cannula into the dorsum of the hand.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

How to record an ECG. Demonstrates placement of chest and limb electrodes.

Chronic or recurring hypotension

Specific symptoms of chronic illnesses known to predispose to either chronic or recurring hypotension should be sought. Such illnesses include:

Diabetes mellitus

Addison's disease

Parkinsonism (including Parkinson's disease and Parkinson's plus syndromes, such as multi-system atrophy)

Chronic liver disease

Symptoms of these conditions should alert the clinician to the need for specific laboratory investigations.

Prevalence of various chronic illnesses presenting as hypotension differs based on age.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chronic illness presenting with hypotension based on patient ageCreated by The BMJ Group [Citation ends].

Younger adults

Exclusion of pregnancy via historical enquiry and pregnancy testing is appropriate in all women of child-bearing age.

A neurally mediated reflex syncope should be suspected in younger adults with a past medical history of syncopal symptoms in childhood and a positive family history of vasovagal syncope, but with no other current symptoms.[77] The precipitant provoking event varies from syndrome to syndrome (e.g., in vasovagal syncope prolonged standing is a common precipitant, whereas in other situational syndromes the precipitant may be micturition, postprandial state, cough, sneeze, visceral pain, post-exercise, brass instrument playing, and weightlifting.[16]

Primary autonomic failure or primary amyloidosis may also be considered if symptoms of hypotension are occurring on a daily basis.[78][79][80]

Any adult age group

Secondary amyloidosis may occur in younger or older patients.

Diabetes mellitus (leading to diabetic neuropathy with orthostatic hypotension), Addison's disease, and chronic liver disease can exist in younger or older patients.

A history of chronic fatigue, itch, muscle or joint pains may indicate chronic liver disease. Patients with diabetic neuropathy may have evidence of painless injuries, commonly to their feet, and orthostatic hypotension on testing. Patients with a known history of malnutrition (especially in the setting of alcohol abuse), bowel surgery, prolonged parenteral nutrition, hyperemesis gravidarum, or other cause of chronic vomiting should be suspected of thiamine deficiency.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plantar ulcer in a patient with type 1 diabetesFrom the collection of Rodica Pop-Busui, University of Michigan, MI; used with permission [Citation ends].

Older adults

Older patients are more likely to present with chronic persistent or paroxysmal arrhythmias, and parkinsonism. Hypotension prevalence in idiopathic Parkinson's disease increases with disease duration, whereas it is an early feature of disease in patients with Parkinson's plus syndromes (e.g., multi-system atrophy). One prospective study reported a cumulative prevalence of orthostatic hypotension in patients with Parkinson’s disease of over 65% after 7 years. Almost 30% of patients had clinically significant orthostatic hypotension.[81]

Older adults are also more likely to develop hypotension secondary to vitamin B12 deficiency than younger adults, as this diagnosis increases in prevalence with age.[82]

Several forms of neurally mediated reflex syncope (e.g., micturition syncope) occur more commonly in older patients, and should be suspected by their history.[83]

The carotid sinus syndrome only occurs in patients over 50 years, and is rare in patients under 70 years.[84] A classical history of syncope (secondary to hypotension) occurring after turning or extending the neck is not always present.

Examination:

Patients with no acute cardiogenic cause for hypotension should be placed supine in bed while undergoing evaluation. In patients with suspected vasovagal syncope or situational syncope it is often helpful to elevate their legs for a short period of time while their blood pressure normalises. Nursing staff should be alerted to their potential falls risk.

Should include a check for signs of Addisonism (e.g., hyperpigmentation) or hypopituitarism (dry skin, loss of axillary or pubic hair).

Signs of chronic liver disease should be sought (e.g., jaundice, hepatomegaly, peripheral oedema. ascites, spider naevi, caput medusa).

Diabetes mellitus, vitamin B12 deficiency, and thiamine deficiency are all potential causes of hypotension if a patient has evidence of peripheral neuropathy on physical examination.

Patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope, and those with primary autonomic failure will usually have an unremarkable physical examination. The latter may be difficult to distinguish from primary amyloidosis on physical examination alone, although macroglossia, lower limb oedema or purpura may be present in amyloidosis.

Palpate for a gravid uterus in women of childbearing potential with no other apparent cause of hypotension.

Investigations:

Include:

FBC (the presence of macrocytosis may suggest the presence of vitamin B12 deficiency, chronic liver disease, thiamine deficiency or hypothyroidism)

Blood glucose (if undiagnosed diabetes is suspected it is usually confirmed with a fasting blood glucose, or an elevated serum haemoglobin A1C)

Serum electrolytes (hyponatraemia may indicate Addison's disease, hypothyroidism or chronic liver disease if secondary hyperaldosteronism is present)

Serum transaminases and bilirubin

Coagulation profile

A 12-lead ECG.

Additionally for older adults, the following should be considered:

Thyroid function tests (TSH and free T4)

Serum vitamin B12 concentration (vitamin B12 deficiency is confirmed by the presence of a vitamin B12 concentration in the deficiency range)

Further investigations are as follows:

A urinary beta human choriogonadotrophin: to confirm pregnancy.

Thiamine deficiency can be confirmed by serum thiamine pyrophosphate concentration.

Chronic liver disease is usually supported by the presence of deranged serum transaminases, by impaired synthetic function markers (e.g., elevated international normalised ratio, elevated bilirubin), appropriate imaging and liver biopsy (at a later date).

Addison's disease can be confirmed by the presence of a low serum cortisol and an inadequate response to administration of tetracosactide.

Hypopituitarism can be confirmed by demonstration of evidence of hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency combined with a low follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinising hormone, with reduced serum estradiol in women, or reduced serum testosterone in men. TSH and ACTH are also inappropriately low in relation to levels of thyroid hormone and cortisol.

The presence of amyloidosis can be confirmed by tissue biopsy and staining with Congo Red (positive/green birefringence).

Tilt table testing has a variable level of sensitivity in the presence of neurally mediated reflex syncope which is best diagnosed clinically. It may help to confirm the diagnosis of vasovagal syncope (reproduction of symptoms with prolonged [40 min] tilt).[16][85][86] It may also be used with carotid sinus massage to help diagnose older people with suspected carotid sinus syndrome. Patients have a symptomatic fall in BP ± syncope precipitated by carotid sinus massage. Patients with the pure vasodepressor subtype do not have an associated cardiac pause, unlike patients with the cardio-inhibitory subtype who have an associated inducible cardiac pause/asystole exceeding 3 seconds.[16]

The presence of primary autonomic failure can be confirmed by a number of specialised tests including: 1) plasma noradrenaline (norepinephrine) - failure to release noradrenaline (norepinephrine) on standing; 2) deep breathing - diminished beat-to-beat variation on ECG during inspiration and expiration; 3) valsalva manoeuvre - failure of the BP overshoot after release of the strain; 4) electrophysiological testing - reduction in sensory nerve conduction velocity; muscle denervation; 5) quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test - absence of sweat production; 6) heart rate variability - decreased heart rate variability.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer