Approach

Assessment of abdominal trauma is often difficult due to confounding factors, such as an altered mental status, simultaneous extra-abdominal injuries, or lack of a history.[1] Missed or delayed diagnosis of an abdominal injury may lead to unfavourable patient outcomes.[17] An organised team approach to the diagnostic work-up of abdominal trauma is necessary as resuscitation and evaluation of other systems happen concurrently. The diagnostic approach varies according to the haemodynamic stability of the patient. Priorities in the evaluation of abdominal trauma are to recognise haemodynamic instability and determine the need for urgent laparotomy.

Clinical history

A dedicated attempt to quickly gather a clinical history and description of the traumatic event from the patient, emergency medical personnel, police, or family members is necessary, and may provide information that influences the diagnostic work-up.

A description of the traumatic event aids the understanding of the mechanism of injury. If the patient was involved in a motor vehicle accident, it is useful to know the speed at which the car was travelling, the amount of damage at the scene, extrication time, use of seat belts or airbags, and whether there was a fatality at the scene. This information may be useful to gain an appreciation of the amount of energy transferred to the patient during the event.

Information on the clinical status of the patient and the amount of resuscitation given en route to the hospital aids the estimation of the current haemodynamic status of the patient. The suspicion of active bleeding is higher in hypotensive patients who have already received multiple litres of fluid than in those where resuscitation has not been given.

Past medical and drug histories are useful to establish the baseline level of health of the patient.

It is important to consider the cause of a traumatic event to prevent an underlying medical condition from going unrecognised and untreated. For example, hypoglycaemia in a patient with diabetes or a heart attack in a patient with coronary artery disease may have been the initiating factor of the traumatic event.

Knowledge of whether a bleeding patient is on an anticoagulant medication may affect the amount, type, and timing of the blood products transfused. Patients on antihypertensive or heart rate-controlling medications do not have the same physiological response to blood loss as those who do not take such medicines.

Physical examination

While physical examination is essential in evaluating abdominal trauma, many studies have demonstrated that it is unreliable in trauma patient cohorts with neurological injury (brain or spinal cord), in those with painful distracting injuries such as long bone or pelvic fractures, or in those with alcohol or other intoxicants in their systems.[23][30][31]

Evaluation of the abdomen begins with inspection for external signs of injury such as open wounds, or significant bruising of the abdominal wall. Palpation of the abdomen is used to assess for tenderness and peritoneal signs. Many, although not all, patients with an abdominal injury complain of tenderness, and peritoneal signs may be present if the bowel is injured. It should be noted that blood in the peritoneal cavity does not cause peritonitis.

In addition to the basic examination, in penetrating trauma it is useful to assess entrance and exit wounds for active bleeding or protruding omentum or viscera. Local wound exploration of a stab wound in a haemodynamically stable patient without signs of peritonitis is beneficial to assess the abdominal fascia. If the anterior abdominal fascia is intact and the patient remains stable, it is safe for the patient to be discharged home without further work-up.[32]

Assessment of haemodynamic status

On initial assessment, less than one half of patients with significant haemoperitoneum have significant findings on physical examination. Young, healthy patients have a powerful physiological compensatory response to haemorrhage and thus tolerate large amounts of blood loss while remaining relatively asymptomatic without manifesting common signs such as hypotension or changes in mental status. Patients on beta-blockers, or older adults who have a diminished compensatory response to haemorrhage, may not be tachycardic during the early phases of shock. There is greater danger of a delayed diagnosis of shock in these patients due to atypical presenting signs and symptoms.

In all patients, the key to the recognition of haemorrhagic shock is integration of the mechanism of injury, current symptomatology, and changes in vital signs relative to the amount of intravenous fluid resuscitation received by the patient.

Abdominal trauma patients who present with signs of haemorrhagic shock respond to intravenous fluid resuscitation in one of three ways:

Vital signs normalise with intravenous fluid replacement. The majority of these patients have experienced intravascular volume loss from bleeding that stopped secondary to effective coagulation and tamponade.

Vital signs transiently respond to intravenous fluid replacement. These patients are likely to have ongoing intra-abdominal bleeding and often require surgery, or possibly angioembolisation, to control the haemorrhage.

Vital signs do not respond to intravenous fluid replacement. The clinical status of these patients deteriorates with continued aggressive resuscitation. These patients typically have a major intra-abdominal arterial injury or a severe solid organ injury, and require immediate surgical control of the haemorrhage to prevent death.

Evaluation of haemodynamically stable blunt abdominal trauma

Haemodynamically stable patients with blunt abdominal trauma who have no complaints of abdominal pain, a non-tender abdomen, and a reliable physical examination (i.e., no distracting injuries, no head injury) do not generally require computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen for further work-up.[21] However, the absence of abdominal tenderness does not rule out completely the possibility of intra-abdominal injury.[33] Combinations of clinical findings to predict the presence of intra-abdominal injury have been studied.[34][35] When there are other factors present that increase the possibility of intra-abdominal injury, such as significant non-abdominal injury (e.g., femoral, pelvic, scapular, or vertebral fractures) that suggest a powerful mechanism of injury, an abdominal CT scan is recommended to evaluate for associated intra-abdominal injury.[30][31]

Patients with abdominal tenderness, abdominal wall contusions, or an unreliable physical examination due to head injury, intoxication, or a distracting injury require further investigation by focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) or an abdominal CT scan to diagnose potential intra-abdominal injury. FAST has the highest likelihood ratio for the presence of intra-abdominal injury. A CT scan of the abdomen is highly sensitive for the diagnosis of solid organ injury, vascular injury, and pelvic fractures, and is the radiographic study of choice to rule out intra-abdominal injury. It is less effective in the diagnosis of diaphragmatic or bowel injuries. Disadvantages of abdominal CT scanning are that it exposes the patient to radiation and intravenous contrast dye, is expensive, is relatively time-consuming, and requires transfer of the patient to a scanner.[36]

The presence of free intraperitoneal fluid on an abdominal CT scan, without evidence of a solid organ injury, raises concern of a hollow organ injury. In this group of patients, diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) may be useful.[26]

DPL involves making a small midline incision below the umbilicus and using a needle and small catheter to aspirate intraperitoneal fluid to assess for blood or bile. If the aspirate is found to contain 10 mL of gross blood or bile, an exploratory laparotomy is indicated. In the absence of gross blood or bile, DPL requires 1 litre of fluid to be infused into the peritoneum and then drained. The effluent should be sent to the laboratory and evaluated. Laboratory criteria for a positive DPL are:

>1.0 ×10¹² red blood cells/L (>100,000 red blood cells/mm³)

>0.50 × 10⁹ white blood cells/L (>500 white blood cells/mm³)

Presence of bacteria, bile, or food particles.

Although DPL in stable patients has limited utility, it is useful in those with other factors that increase the suspicion of intra-abdominal injury. If a follow-up abdominal CT scan is performed, the additional fluid in the abdomen secondary to DPL can confuse the picture. In stable patients, DPL is an excellent adjunctive study when serial abdominal examinations cannot be performed.[26] An example of this is in the obtunded patient who has free fluid on abdominal CT scanning with no solid organ injury identified. In the awake patient, serial physical examinations and the presence of peritoneal signs or worsening abdominal pain may signify the need for an operation.

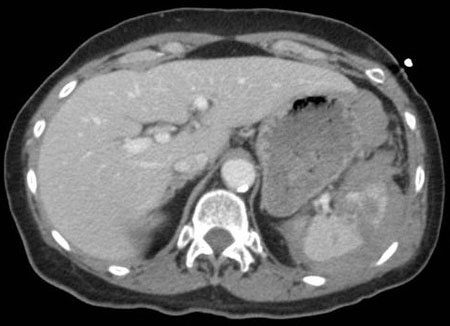

Laboratory evaluation is useful to acquire a baseline haematocrit level, as many patients with blunt abdominal trauma will be haemodynamically stable but have evidence of some intra-abdominal solid organ bleeding on abdominal CT scanning. These patients should be followed as inpatients, with serial abdominal examinations and haematocrit levels to observe for continued bleeding. If there is a steady decline in the haematocrit level, blood transfusion or intervention to control the bleeding may be required. A basic metabolic panel is useful to determine baseline kidney function. Pancreatic enzymes are occasionally useful in the diagnosis of a pancreatic injury, although they are not a sensitive study as part of the initial trauma work-up. Toxicology may be useful in the assessment of a patient with altered mental status.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing hepatic lacerationCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing intraperitoneal fluidCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing intraperitoneal fluidCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends].

Evaluation of haemodynamically unstable blunt abdominal trauma

In haemodynamically unstable patients with blunt abdominal trauma, evaluation and resuscitation occur concurrently. The goal of evaluation is to determine the site of bleeding and at the same time initiate appropriate therapy for control of the bleeding. Haemodynamically unstable patients require at least two large-bore peripheral intravenous lines for aggressive resuscitation with blood products and fluids and a Foley's urinary catheter to allow accurate monitoring of urine output. It is also important to ensure that the patient has a secure airway at all times, as patients often have a reduced level of consciousness and can deteriorate rapidly.[14]

If peripheral intravenous lines are difficult to place, a short, large-calibre femoral or subclavian line is recommended. Long double- or triple-lumen central lines should be avoided as fluid cannot be infused rapidly through this type of catheter. Blood should be drawn for crossmatch and multiple units of packed red blood cells prepared in anticipation of transfusion. Patients with profound haemorrhagic shock, suggested by extreme hypotension and a severely altered mental status (i.e., coma), require immediate un-crossmatched blood transfusion.

Radiographs performed in the trauma suite are useful to rule out a haemothorax or pelvic fracture.[37] A FAST examination is useful to quickly diagnose intra-abdominal haemorrhage.[23][24] The FAST examination uses a bedside ultrasound to provide images of the right upper quadrant, left upper quadrant, and pelvis to assess for intra-abdominal haemorrhage.[21] In 2006, a study from the UK found the FAST examination to have a sensitivity of 78% and a specificity of 99% in the detection of intra-abdominal haemorrhage.[38] A systematic review found that the presence of intraperitoneal fluid or organ injury on ultrasound is more accurate than any history and physical examination findings in the diagnostic evaluation for intra-abdominal injuries after blunt abdominal trauma.[33] If a FAST examination is unavailable or unreliable, a DPL may be performed to assess for intraperitoneal bleeding.[26]

Patients found to have significant free intra-abdominal fluid according to FAST examination (or DPL) and haemodynamic instability should undergo urgent surgery.[39]

Evaluation of penetrating abdominal trauma

The majority of cases of penetrating abdominal trauma are related to gunshot wounds (GSWs) and stab wounds. After assessment of the airway, breathing, and circulatory status, it is important to completely expose the patient to identify all the wounds.

Patients presenting with signs of peritonitis, or haemodynamic instability, require an urgent laparotomy.[40] They should thus undergo immediate preparation for surgery with a secure airway, two functioning large-bore peripheral intravenous lines, a Foley's catheter, and preoperative labs including a type and crossmatch.

Stable patients may undergo further evaluation in a timely fashion. Those with stab wounds to the abdominal wall require local wound exploration to evaluate for perforation of the abdominal wall fascia. Local wound exploration is performed by prepping the field and cleaning the wound and surrounding skin. After injection of a local anaesthetic, the skin and subcutaneous tissues are incised with a large enough incision for the abdominal wall fascia to be adequately visualised. If the anterior fascia has not been violated, it is safe to assume that the intra-abdominal organs have not been injured. Patients with wounds that penetrate the abdominal fascia require further evaluation and close observation with serial abdominal examinations, laparoscopy to rule out intra-abdominal organ injury, or immediate laparotomy.[32]

For stab wounds to the flank or back, it is necessary to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen to rule out intra-abdominal injuries (e.g., colonic, splenic, or kidney injuries). Commonly, stab wounds to the flank result in kidney lacerations that are usually managed non-operatively.

Gunshot wounds to the abdomen are typically managed operatively regardless of the clinical status of the patient.[40] Plain films of the chest and abdomen with metallic markers (e.g., paper clip) over entrance and exit wounds (if present) should be urgently ordered to determine the trajectory of the bullet. Bullets can take unexpected paths through the body and it is important to rule out chest injuries prior to surgical exploration of the abdomen. Knowledge of the bullet trajectory is also useful for the surgeon to preoperatively predict intra-abdominal injuries.

In trauma centres with considerable experience of penetrating trauma, there has been some interest in the observation of select patients with gunshot wounds, primarily right thoraco-abdominal wounds, in preference to undertaking immediate laparotomy.

[  ]

This carries the risk of missing important intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal injuries, and should be very cautiously considered in facilities where gunshot wounds are only occasionally managed. As non-operative management of isolated hepatic injury has been shown to be successful, an abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast may be considered in stable patients with bullet trajectories suggestive of such an injury.[41][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic view of diaphragm injuryCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends].

]

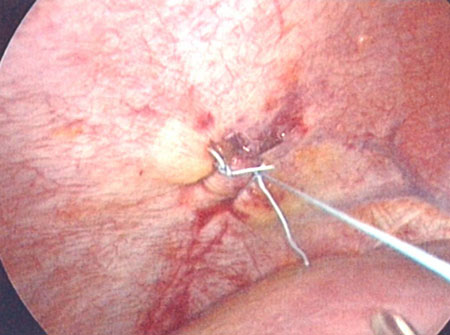

This carries the risk of missing important intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal injuries, and should be very cautiously considered in facilities where gunshot wounds are only occasionally managed. As non-operative management of isolated hepatic injury has been shown to be successful, an abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast may be considered in stable patients with bullet trajectories suggestive of such an injury.[41][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic view of diaphragm injuryCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic repair of diaphragmCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic repair of diaphragmCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing splenic lacerationCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing splenic lacerationCollection of the MetroHealth Medical Center [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer