Approach

Typically, actinomycosis presents as a chronic, slowly progressive, indurated mass. Clinical symptoms may be very subtle. Pain, fever, and fatigue, though sometimes present, are often absent. Characteristic lesions usually develop slowly, over weeks to months.

Actinomycosis has often been called the 'great pretender' or the 'great masquerader' of head and neck diseases, reflecting the fact that the symptoms are not specific and may be found in other, much more common conditions. Thus, the inclusion of actinomycosis in the differential diagnosis of other possible diseases is often the only means to an early and correct diagnosis.

Actinomycosis is usually diagnosed only after surgery for treatment of an abscess or tumour. Only rarely is the diagnosis made before surgery. Macroscopic and histological analyses of the pus from draining sinuses and detection of sulfur granules are highly indicative of actinomycosis, and may be confirmed by cultivation of actinomycetes.[7]

Actinomycosis is more common in patients with diabetes mellitus and in those who are immunosuppressed. It often develops in tissues that have been damaged by neoplasia, trauma, or irradiation.[13] It is more common in males than females.

Cervicofacial actinomycosis

Most cases of cervicofacial actinomycosis are odontogenic, and often result from injury or inflammation in the oral cavity.[27] However, primary infections have also been reported from other structures within the head and neck, sometimes anatomically significantly removed from any potential periodontal source.[33][34]

Typically, cervicofacial actinomycosis presents as a chronic, slowly progressive, indurated mass, which develops into multiple abscesses, fistulae, and draining sinus tracts.[35]The visible inflammation is often more severe than the pain.

The involved skin may appear bluish or reddish.[35] Over time, sinus tracts and fistulae develop on the skin or mucosa, which may erupt and express a thick, yellow serous exudate containing so-called sulfur granules, which can sometimes be seen with the naked eye. Cervicofacial actinomycosis may involve almost any tissue or structure surrounding the upper or lower mandible, and the mandible itself is often involved during infection.[35] Fistulisation from the perimandibular region may be a first diagnostic clue. Chewing may be difficult if the muscles of mastication are involved. A mass may be visible on CT or MRI, but this is unlikely to be diagnostic.

In a relatively large series of 317 patients, the presenting sites were:[36]

Mandible (54%)

Cheek (16%)

Chin (13%)

Submaxillary ramus and angle (11%)

Upper jaw (6%).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Example of the clinical picture of a cervicofacial actinomycosisFrom the collection of Dr Juergen Ervens, Head, Department of Oral and Plastic Maxillofacial Surgery, Charité - University Medicine Berlin, CBF, Berlin, Germany [Citation ends].

Abdominal and pelvic actinomycosis

Between 10% and 20% of all reported cases of actinomycosis are located in the abdomen or pelvis.[20] Typically, these patients have a history of tissue injury caused by recent or remote bowel surgery or ingestion of foreign bodies, during which actinomycetes were able to enter the deep tissues.[16] The infection typically presents as a slowly growing mass, and most frequently involves the ileocaecal region.[37][38] The mass may be visible on imaging studies such as MRI or CT, but the diagnosis is usually established only after exploratory laparotomy, by histology.

Intestinal actinomycosis may be misdiagnosed as Crohn's disease, malignancy, or intestinal tuberculosis. Any abdominal organ, including the abdominal wall, can be involved by direct spread, with eventual formation of draining sinuses.[4][14][39][40][41]

Symptoms are often non-specific, and may include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort. Some patients report the sensation of a mass in the abdomen.

Pelvic actinomycosis most commonly ascends from the uterus, and is usually caused by intrauterine devices (IUDs) that have been in situ and not replaced for many years. Patients may present with vaginal discharge or bleeding. Lower abdominal discomfort is also sometimes reported. Physical findings may include a palpable mass, visible sinus tracts, or fistulae.

Other manifestations

Thoracic actinomycosis is frequently misdiagnosed as malignant disease.[21][22][23] Actinomycosis may develop at any site in the chest, but it is most common at sites where the mucosal surface is altered or at sites of previous injury. Aspiration, as occurs in conditions such as dementia or alcoholism, enhances the risk of pulmonary actinomycosis.[32] Symptoms referable to the chest are usually non-specific, and are determined by the location and the local extension. They may include a cough, which can be dry or productive of sputum that may be blood-streaked; shortness of breath; and chest pain. Most patients present with local tumours visualised by radiological procedures.[21][22][23] In pulmonary actinomycosis, sinus tracts with sulfur granules may appear and are a strong diagnostic hint.

Actinomycosis may affect any organ or body system, including the central nervous system, presenting in most cases as brain abscess and rarely as meningitis or meningoencephalitis, actinomycoma, subdural empyema, or epidural abscess.[24][25] Other locations may be the skin, eye, or soft tissues.[42][43][44][45][46][43]

Laboratory tests: general considerations

Because actinomycosis is rare, and symptoms and physical findings, as well as laboratory results, are non-specific, diagnosis is usually made late in the course of the disease.[7] Full blood count may show anaemia and leukocytosis.[2][29][30][31] Even in specialist clinics, the time from first symptoms to diagnosis is frequently longer than 6 months.[21] The cornerstones of definitive diagnosis are:[47]

Direct cultivation of the agent from affected tissue

Histology and immunohistology.

Culture

Actinomycosis is usually diagnosed by culturing the pathogen from affected tissue. Typically, needle aspirates from an abscess, fistula, or sinus tract are used, although sometimes larger biopsy specimens are required. Care should be taken to avoid contamination with other bacteria. Specimens should be incubated under strict anaerobic or at least microaerophilic conditions. Culture requires a minimum of 14 days.[1] As culture techniques need to be meticulous and long incubation is required, clinicians should specifically request actinomycosis culture on the laboratory request form.[7] False-negative results are not uncommon.

Moreover, patients have often already been treated with antibiotics before the differential diagnosis of actinomycosis is considered. In such cases, culturing the agent is difficult or impossible. Therefore, although culture of the organism from affected tissue is the preferred diagnostic test, in many cases the diagnosis can be made only by histology or immunohistology.

Histology and immunohistology

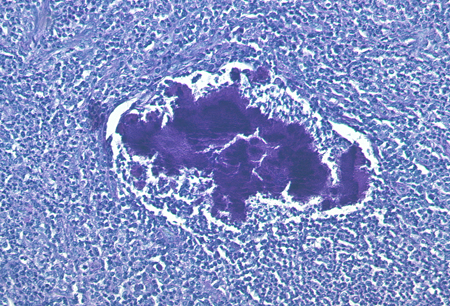

Biopsies from the affected tissue should be used not only for culture but also for additional histological work-up. Sections from biopsies reveal acute or chronic inflammation and granulation. Neutrophils, foamy macrophages, plasma cells, and lymphocytes surrounding dense fibrotic tissue are usually found.

A hallmark of actinomycosis is the presence of so-called sulfur granules, which are formed by the actinomycetes within the infected tissue.[7] This term may be misleading, because the granules do not contain sulfur. Rather, the name reflects the yellow colour of the granule in pus. Sulfur granules may be seen in only a few sections and in low density, and sometimes more than 1 biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis by this method.

The granules are often discrete, about 100 to 1000 micrometres in diameter, and are often seen directly without magnification or under the microscope with low magnification. The granules are composed of a protein-polysaccharide complex and are mineralised by host calcium and phosphate.[35] The appearance has been described as internal mycelial fragments surrounded by a rosette of peripheral clubs. Although these granules are typical for actinomycosis, similar granules may also be found in infections with other organisms (e.g., Nocardia brasiliensis or Streptomyces madurae), although the granules of bacteria other than actinomycetes usually lack the peripheral clubs.

Classifying the causative micro-organism solely by non-specific histological staining (haematoxylin and eosin, Gram, Ziehl-Neelsen, periodic acid-Schiff) is not possible. Immunohistological techniques using species-specific staining with fluorescent-conjugated monoclonal antibodies have improved diagnostic procedures. They identify the infecting actinomycete species reliably, and allow discrimination from other bacteria.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Periodic acid-Schiff stain of a mass of actinomycetes in a lymph nodeFrom the collection of Professor Dr Christoph Loddenkemper, Department of Pathology, Charité - University Medicine Berlin, CBF, Berlin, Germany [Citation ends].

Other laboratory techniques

Other approaches have been used to try to improve the diagnostic tools for actinomycosis. PCR techniques have been developed for the various species of actinomycetes. However, no standardised protocols exist. PCR is used mainly in research studies, and has not yet become part of routine diagnostic practice. Serology has so far not improved the diagnosis of actinomycosis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer