Approach

A detailed history of the quantity and duration of alcohol ingestion, together with a physical exam and appropriate laboratory tests, is essential in the diagnosis of ARLD. Key risk factors include prolonged heavy alcohol consumption, presence of hepatitis C, and female sex.

Asymptomatic elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in a person consuming alcohol in excess is a common mode of presentation. It is important to emphasise that the signs, symptoms, histological stages, and severity of liver disease are variable among individuals with ARLD. In addition, relatively asymptomatic patients may have histologically advanced liver disease. Clinical decompensation carries a poor prognosis regardless of the histological stage of ARLD. Patients with ARLD may have more than one pattern of alcohol-related liver damage simultaneously. For example, they may have alcohol-related hepatitis on a background of cirrhosis.

History

A thorough history of alcohol consumption from patients and sometimes their family members is critical. Popular questionnaires used to assess the presence of alcohol dependency are AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test), AUDIT-C, and CAGE.[37][38][39] [ Alcohol Consumption Screening AUDIT Questionnaire Opens in new window ] The CAGE questionnaire is easier to use, but AUDIT and AUDIT-C are more reliable.

AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) questionnaire

The AUDIT questionnaire, developed by the World Health Organization, consists of 10 questions. A score of 8 or more (≥7 for age >65 years) indicates alcohol use disorder and alcohol dependence with sensitivity >90% and specificity >80%, while a score of >3 in a man or >2 in a woman indicates alcohol use disorder with sensitivity >80%. An overall score of >4 in men or >2 in women identifies 84% to 86% of patients with an alcohol use disorder.[40] The American College of Gastroenterology and the European Association for the Study of the Liver both recommend the AUDIT questionnaire.[1][41]

AUDIT-C 3-item alcohol screen

Identifies people who are hazardous drinkers, or who have alcohol use disorder. It is a modified version of the 10-question AUDIT questionnaire. AUDIT-C comprises three questions asking about frequency of alcohol use, typical amount of alcohol use, and occasions of heavy use. AUDIT-C takes approximately 1-2 minutes to administer.

CAGE questionnare

The CAGE questionnaire takes its name from its 4 simple questions and is a useful screening tool for alcohol misuse or dependency:

C: Have you ever felt you needed to CUT down on your drinking?

A: Have people ANNOYED you by criticising your drinking?

G: Have you ever felt GUILTY about drinking?

E: Have you ever felt you needed a drink first thing in the morning (EYE-OPENER) to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover?

Two or more positive answers indicate alcohol dependency with sensitivity of 70% to 96% and specificity of 91% to 99%.[38][39]

Symptoms

Do not directly reflect the presence or severity of ARLD, and clinical manifestations may vary. Typical symptoms include:

Fatigue

Anorexia

Weight loss

Jaundice

Fever

Nausea and vomiting

Right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort.

In advanced liver disease, patients may present with symptoms of severe hepatocellular failure, such as:

Abdominal distension and weight gain (ascites)

Confusion (hepatic encephalopathy)

Haematemesis or melaena (gastrointestinal bleeding)

Asterixis

Leg swelling

Fever in the absence of infection can occur in patients with ARLD.[41]

Physical examination

Ambulatory patients with early-stage ARLD often do not have major findings on physical examination, or may have only hepatomegaly, mild jaundice, or low-grade fever (even in the absence of infection). Patients with advanced ARLD may have signs of portal hypertension, including:

Ascites

Splenomegaly

Venous collateral circulations.

The consequences of ascites are related not only to aesthetic body shape changes but also to the high risk of spontaneous infection of the fluid, development of abdominal hernias, difficulty in breathing, decreased food intake, and progressive malnutrition, as well as decreased physical activity with loss of muscular mass.[42]

Signs of significant or severe hepatic involvement include:

Confusion (hepatic encephalopathy)

Cutaneous telangiectasias

Palmar erythema

Finger clubbing (often from hypoxaemia due to hepatopulmonary syndrome)

Dupuytren's contracture

Parotid gland enlargement

Feminisation (gynaecomastia, hypogonadism)

Poor nutritional status, muscle wasting, peripheral neuropathy, dementia, or cardiomyopathy may co-exist with ARLD because of chronic alcohol use. Hepatic mass is an ominous finding suggesting hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It should be noted that most of the symptoms and signs listed are common to all chronic liver diseases and are not specific for ARLD.

Initial blood tests

Liver-related biochemical tests (AST, ALT, gamma-GT, ALP, albumin, bilirubin)

Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are markers of alcohol-induced liver injury. However, it is important to note that AST and ALT can be normal in the absence of significant liver inflammation (a reassuring sign) or in advanced cirrhosis (in which there are few viable hepatocytes left to produce the transaminases, a sign of end-stage disease).[43]

In patients with ARLD, the AST level is almost always elevated (usually above the ALT level). The classic ratio of AST/ALT >2 is seen in about 70% of cases.[44] Reversal of the ratio suggests the concomitant presence of viral hepatitis, or possibly metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Gamma glutamyl transferase (gamma-GT) is frequently elevated in heavy drinking, but is not specific for alcohol use. It is helpful in identifying patterns of alcohol misuse. Elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) may represent cholestasis associated with ARLD. Concomitant elevated GGT and ALP indicates the liver as the source of the ALP, because GGT is not significantly present in bone.[45]

Albumin and bilirubin are markers of hepatocellular function. Low albumin reflects impaired liver synthetic function; elevated bilirubin, in the absence of biliary obstruction, is typically due to parenchymal liver disease.

Full blood count

Anaemia is common in ARLD and has multiple causes, including iron deficiency, gastrointestinal bleeding, folate deficiency, haemolysis, and hypersplenism. Leukocytosis may be from an alcohol-related hepatitis-related leukemoid reaction or an associated infection. Thrombocytopenia may be secondary to alcohol-induced bone marrow suppression, folate deficiency, or hypersplenism. A high mean corpuscular volume (MCV) may also indicate liver disease.

Basic metabolic panel (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, urea, creatinine)

Hyponatraemia is usually present in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Hypokalaemia and hypophosphataemia are common causes of muscle weakness in ARLD.

Magnesium and phosphorus

Hypomagnesaemia can cause persistent hypokalaemia and may predispose patients to seizures during alcohol withdrawal. Hyperphosphataemia predicts poor recovery in advanced liver disease.

Coagulation profile (PT, INR)

Prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and international normalised ratio (INR) indicate diminished hepatic synthetic function in advanced liver disease with cirrhosis or liver failure in patients with ARLD.

Coagulopathy is an obvious complicating factor in cases of gastrointestinal bleeding from varices or gastropathy.

Subsequent laboratory tests to rule out co-existing diseases

Serum laboratory tests to rule out other significant diseases and comorbidities that may co-exist with ARLD include the following:

Viral hepatitis serological panel (for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C)

All patients should be screened for hepatitis A total antibody and hepatitis B surface and total-core antibodies, in order to plan for immunisations. To exclude co-existent viral hepatitis, patients can be tested for immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-hepatitis A, hepatitis B surface Ag, and IgM anti-hepatitis B core, and for hepatitis C RNA by polymerase chain reaction.

Iron studies (for haemochromatosis) and copper studies (for Wilson's disease)

Elevated ferritin is common because it is an acute-phase reactant, and sometimes due to secondary iron overload.[46] Iron distribution in tissue, hepatic iron index, and genetic studies for haemochromatosis can help to clarify the co-existence of ARLD with haemochromatosis.

Increased urinary copper, very high liver copper, and decreased serum ceruloplasmin indicate Wilson's disease.

Ammonia level and folate

The serum ammonia level may be elevated but does not always correlate with the presence or severity of hepatic encephalopathy (unless it is extremely high). Therefore, a finding of elevated serum ammonia is not required to diagnose ARLD or hepatic encephalopathy.

Reduced intake and increased requirements of folate in hepatic disease may lead to folate deficiency.

Anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-nuclear antibody, and anti-smooth muscle antibody

Anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) is used to test for co-existent primary biliary cirrhosis. ANA (anti-nuclear antibody) and ASMA (anti-smooth muscle antibody) are used to rule out the presence of associated autoimmune hepatitis.

Alpha-1 antitrypsin

Alpha-1 antitrypsin phenotype may need to be investigated if there is a personal or family history of emphysema.

Other serum laboratory tests that may indirectly reflect the presence of alcohol misuse

Among these are phosphatidylethanol, carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) and mitochondrial AST.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine and American Psychiatric Association suggest the use of alcohol biomarkers as an aid to diagnosis, to support recovery, and as catalysts for discussion with the patient, rather than as tools to 'catch' or punish patients.[47]

The authors utilise phosphatidylethanol in blood with a cut-off of 20 ng/mL to indicate recent alcohol consumption (sensitivity 79% to 100%; specificity 91% to 99%; positive predictive value 85%; negative predictive value 100%) due to its excellent negative predictive value.[48]

When clinical suspicion is high and the patient denies alcohol use, a positive CDT test may be helpful to establish alcohol misuse. This is particularly true in young men with alcohol ingestion >60 g/day.[49][50] Serum CDT has a half-life of approximately 15 days and can detect excessive alcohol use for up to 4 weeks before analysis.[51]

Mitochondrial AST is a specific isoform of the AST enzyme released from hepatocytes at high levels in diseases associated with alcohol misuse.[52]

Alcohol biomarkers should not be used on their own to confirm or refute alcohol use but should be combined with other laboratory tests (including other alcohol biomarkers), physical examination, and the clinical interview.

Routine use of alcohol biomarkers is not necessary.

Imaging

Ultrasound should be performed among patients with harmful alcohol use, as it helps diagnose alcohol-related steatotic liver disease.[53]

Ultrasound (or computed tomography [CT] scan) of the abdomen is useful to exclude alternative diagnoses, such as cholecystitis, biliary obstruction, portal or hepatic vein thrombosis, and liver mass when clinically indicated.

Common CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings include irregular liver margins and intrahepatic hypervascularity. Non-contrast plus triphasic contrast CT scan (four phase study) or four-dimensional phase contrast MRI of the abdomen are useful further investigations to evaluate a liver mass detected by ultrasound. They are also used to search for a tumour in patients with an elevated alpha-fetoprotein and high clinical suspicion of HCC whose ultrasound is negative.

The choice between CT scan and MRI depends on factors such as availability, expertise, quality of equipment, and previous radiation exposure.

Non-invasive markers of chronic ARLD

A number of non-invasive laboratory tests are used to assess liver fibrosis in patients with ARLD, including enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF), fibrosis-4 (FIB-4), and AST to platelet ratio index (APRI).[11][54][55]

The ELF test uses specific molecular markers of fibrogenesis, while other tests use combinations of routinely collected blood tests (e.g., FIB-4, APRI). The utility of these markers is predominantly for excluding severe fibrosis, with normal values being reassuring. They do not perform well at differentiating intermediate stages of fibrosis.[55]

Imaging tests to detect fibrosis

Liver stiffness is the leading biomarker for the detection of advanced fibrosis. Ultrasound shear wave elastography is a non-invasive technique for assessing liver stiffness. Tissue stiffness is deduced from analysis of shear waves that are generated by high-intensity ultrasound pulses.[56] Transient elastography may help to rule out severe fibrosis (F3 or worse) in patients with ARLD.[1][57] Recent alcohol consumption may exaggerate the estimated severity of the fibrosis; thus, it is better to have 2 weeks of alcohol abstinence to increase the reliability of the test.[58] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK recommends transient elastography to diagnose cirrhosis in men who drink more than 50 units of alcohol/week, in women who drink more than 35 units of alcohol/week, and in patients with ARLD.[12]

Magnetic resonance elastography is an alternative technique for assessing liver stiffness. It is more accurate than ultrasound shear wave elastography for identifying fibrosis and cirrhosis, and performs better in people with obesity.[56][59]

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) suggests using imaging-based non-invasive testing to detect advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in adults with ARLD.[60] Either ultrasound-based transient elastography or magnetic resonance elastography is recommended to stage fibrosis.[60] The AASLD advises against using imaging-based tests as a standalone test to assess regression or progression of liver fibrosis.[60]

The French Association for the Study of the Liver recommends that the results of FibroScan®, an elastography device, must be interpreted by considering specific diagnostic thresholds based on AST and bilirubin levels.[61] For the diagnosis of cirrhosis, the threshold is 12.1 kPa (area under receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC] 0.92, sensitivity 85%, specificity 84%) with levels of AST <38.7 IU/L and bilirubin <9 micromol/L, compared with 25.9 kPa (AUROC 0.90, sensitivity 81%, specificity 80%) with levels of AST> 75 IU/L and bilirubin >16 micromol/L. For advanced fibrosis, the thresholds are 8.8 kPa (AUROC 0.92, sensitivity 80%, specificity 75%) and 16.1 kPa (AUROC 0.92, sensitivity 83%, specificity 80%) at the same aforementioned AST and bilirubin levels. Stopping alcohol consumption has an effect on liver elasticity level, with one study showing a decrease in median liver elasticity from 7.2 to 6.1 kPa on day 7. Two weeks of alcohol abstinence will increase the reliability of the test, especially if AST is higher than >100 IU/L.[58]

The European Association for the Study of the Liver has recommended:[59]

For patients with ARLD: liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography <8 kPa to rule out advanced fibrosis. Values higher than 8 kPa should be interpreted taking into account the values of serum AST and bilirubin (see Investigations). In ARLD, the values of transient elastography are not very reliable while actively drinking alcohol. If AST is >100 U/mL, repeat the test after 2 weeks or more of abstinence. Alternative non-invasive tests include ELF™ <9.8, FibroMeter™ <0.45, FibroTest® <0.48, or FIB-4 <1.3.

For patients at risk of ARLD: liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography ≥12-15 kPa to rule out advanced fibrosis after considering causes of false positives.

For patients with elevated liver stiffness and biochemical evidence of hepatic inflammation (>2 times upper limit of normal): repeat liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography after at least 1 week of alcohol abstinence or reduced drinking.

Liver biopsy

Liver biopsy is not required for staging of fibrosis but may be ordered when there are diagnostic uncertainties or suspected competing diagnoses.[1]

Liver biopsy is indicated in patients with atypical presentation to evaluate possible co-existing liver diseases (e.g., haemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, autoimmune hepatitis), to determine the histological severity of liver disease (i.e., presence of cirrhosis), and in patients with clinical evidence of severe alcohol-related hepatitis when medical therapy is contemplated.[1][41][62]

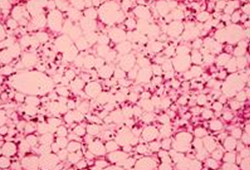

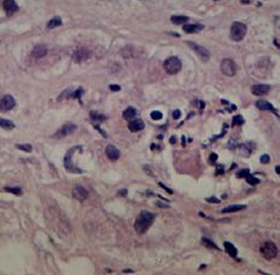

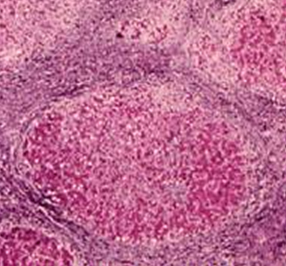

The presence of fatty infiltration in the liver in the absence of inflammation indicates early-stage ARLD with steatosis. Inflammation with necrosis and presence of Mallory bodies indicates alcohol-related hepatitis.[41] Severe fibrosis (usually micronodular, but sometimes mixed macro- and micronodular) starting from the central vein and extending into the portal triad occurs in alcohol-related cirrhosis.[41] The presence of polymorphonuclear cells on liver biopsy may be prognostic for survival of patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis.[63]

Biopsy findings in alcohol-related steatohepatitis and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, previously known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, some drug-induced liver injuries, and Wilson's disease may be identical; thus, the history of alcohol use and appropriate laboratory tests is critical for proper interpretation of the liver biopsy. Special stains and quantitative measurement of copper or iron in tissue can be extremely helpful when the history or laboratory testing raises the question of alternative or co-existing illness.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Liver biopsy showing the typical histological changes of alcohol-related steatosis (fatty liver)From the collection of Dr McClain; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Liver biopsy showing the typical histological changes of alcohol-related steatohepatitisFrom the collection of Dr McClain; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Liver biopsy showing the typical histological changes of alcohol-related steatohepatitisFrom the collection of Dr McClain; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Liver biopsy showing alcohol-related cirrhosisFrom the collection of Dr McClain; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Liver biopsy showing alcohol-related cirrhosisFrom the collection of Dr McClain; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer