Treatment regimens vary depending on the stage of the cancer. Early localised cancers (T1/T2, N0) can be treated with surgery or radiotherapy, with similar survival.[59]Roosli C, Tschudi DC, Studer G, et al. Outcome of patients after treatment for a squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Laryngoscope. 2009 Mar;119(3):534-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19235752?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Cosmidis A, Rame JP, Dassonville O, et al; Groupement d'Etudes des Tumeurs de la Tête et du Cou (GETTEC). T1-T2 N0 oropharyngeal cancers treated with surgery alone: a GETTEC study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004 May;261(5):276-81.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14551793?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: surgery, radiotherapy, or both. Cancer. 2002 Jun 1;94(11):2967-80.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.10567

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12115386?tool=bestpractice.com

The choice of treatment modality is often dependent on size of the primary tumour and location within the oropharynx. Locoregionally advanced cancers can be treated with surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy, or concurrent chemoradiotherapy, with equal outcome.[77]Soo KC, Tan EH, Wee J, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy vs concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III/IV nonmetastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer: a randomised comparison. Br J Cancer. 2005 Aug 8;93(3):279-86.

https://www.nature.com/articles/6602696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16012523?tool=bestpractice.com

Unresectable cancers are treated with chemoradiotherapy, while cancers with distant metastases are treated with chemotherapy for palliation. Consideration should be given to combination therapy of immunotherapy plus platinum-based chemotherapy in the setting of recurrent/metastatic head and neck cancer, as this has been shown to provide a survival benefit.[78]Xu Q, Huang S, Yang K. Combination immunochemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2023 Jun 13;13(6):e069047.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/6/e069047

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37311638?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients should be managed in specialised head and neck centres by a multidisciplinary team that includes otolaryngologists, medical and radiotherapy oncologists, and speech and language pathologists to optimise oncological and functional outcomes.[41]Nguyen NP, Vos P, Lee H, et al. Impact of tumor board recommendations on treatment outcome for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Oncology. 2008;75(3-4):186-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18841033?tool=bestpractice.com

Full blood count, chemical profile, albumin, and pre-albumin should be measured to assess the patient's nutritional status before treatment because of the expected mucositis with radiotherapy or dysphagia after surgery.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends keeping the number of treatment modalities minimum so as to minimise treatment-related toxicity and to preserve function.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

For this reason, evidence of extranodal extension or multiple lymph nodes that will warrant addition of chemotherapy are often used as rationale to offer upfront nonsurgical treatment.

When using radiotherapy, the NCCN recommends intensity-modulated radiotherapy to minimise damage to critical structures.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Treatment deintensification for p16+ oropharyngeal cancer warrants consideration, but at this stage, it should only be done as part of a clinical trial.[79]Adelstein DJ, Ismaila N, Ku JA, et al. Role of treatment deintensification in the management of p16+ oropharyngeal cancer: ASCO provisional clinical opinion. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jun 20;37(18):1578-89.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.19.00441

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31021656?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated tumours are more responsive to treatment and are thus being investigated for de-escalated therapy.[7]Fakhry C, Westra W, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Feb 20;100(4):261-9.

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/100/4/261/908311

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18270337?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Nichols AC, Faquin WC, Westra WH, et al. HPV-16 infection predicts treatment outcome in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Feb;140(2):228-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19201294?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]Lassen P, Eriksen JG, Hamilton-Dutoit S, et al. Effect of HPV-associated p16INK4A expression on response to radiotherapy and survival in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Apr 20;27(12):1992-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19289615?tool=bestpractice.com

With a few exceptions, the treatment regimens for HPV-negative and HPV-positive cancers are similar.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer management

Early-stage (T1/T2, N0, M0 disease)

Patients may be treated with either upfront surgery or radiotherapy.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Even though no randomised study has compared the two modalities, retrospective studies reported similar local control and survival rates, ranging from 80% to 90%.[59]Roosli C, Tschudi DC, Studer G, et al. Outcome of patients after treatment for a squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Laryngoscope. 2009 Mar;119(3):534-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19235752?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Cosmidis A, Rame JP, Dassonville O, et al; Groupement d'Etudes des Tumeurs de la Tête et du Cou (GETTEC). T1-T2 N0 oropharyngeal cancers treated with surgery alone: a GETTEC study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004 May;261(5):276-81.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14551793?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: surgery, radiotherapy, or both. Cancer. 2002 Jun 1;94(11):2967-80.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.10567

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12115386?tool=bestpractice.com

The choice of treatment modality is dependent on size of the primary tumour and location within the oropharynx. Tumours at or approaching the midline (i.e., tumours in the base of the tongue, posterior pharyngeal wall, soft palate, and tonsil invading the tongue base) are at risk of contralateral metastasis and warrant bilateral treatment.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

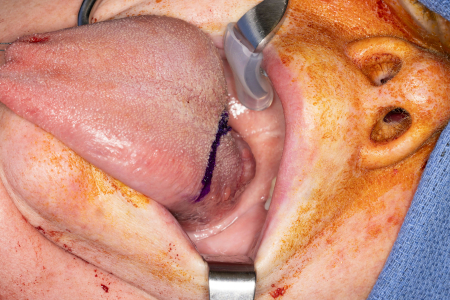

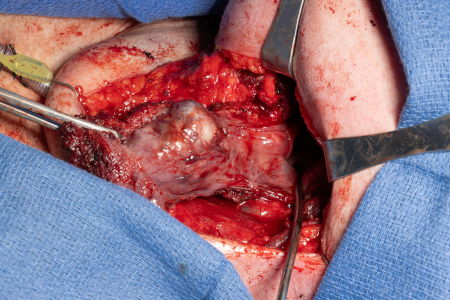

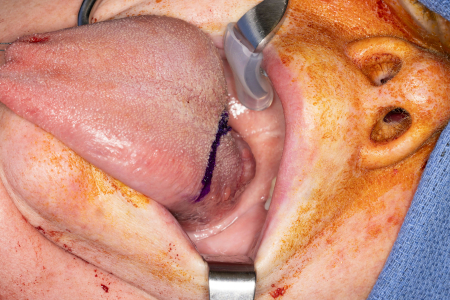

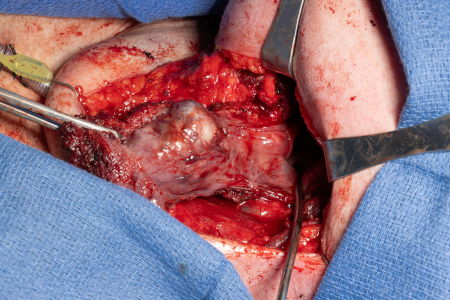

Historically, surgery for oropharyngeal cancer required splitting of the mandible or a pharyngotomy to provide access to the inferior tonsillar fossa or base of tongue.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large base of tongue tumour not amenable to transoral robotic surgery, required open transhyoid approach to the base of tongueFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transhyoid open approach to a large base of tongue tumourFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transhyoid open approach to a large base of tongue tumourFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].

Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) is an innovative technique for early-stage oropharyngeal cancer that allows sparing of the mandible compared with conventional surgery.[82]Parikh A, Lin D, Goyal N. Clinical outcomes of transoral robotic-assisted surgery for the management of head and neck cancer. Robot Surg. 2023 Feb 20;2(2015):95-105.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/RSRR.S70549

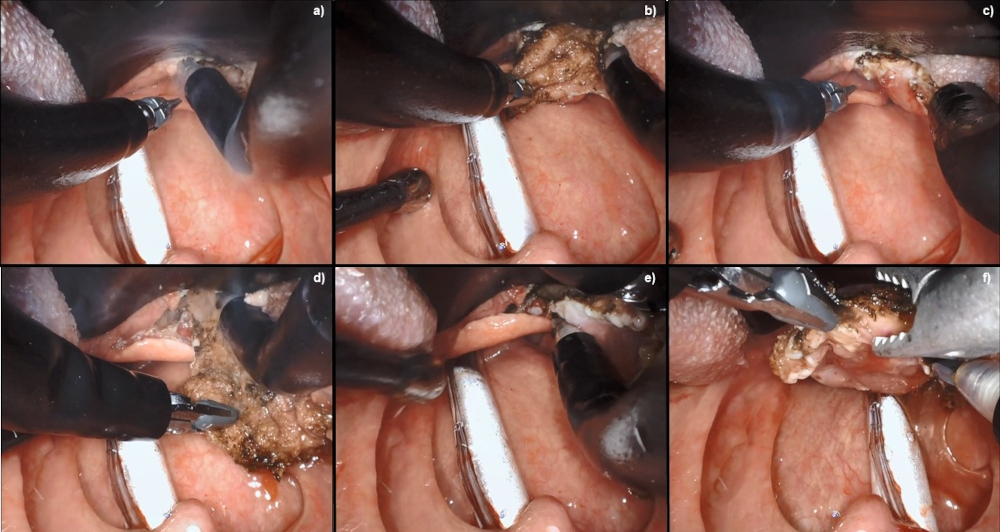

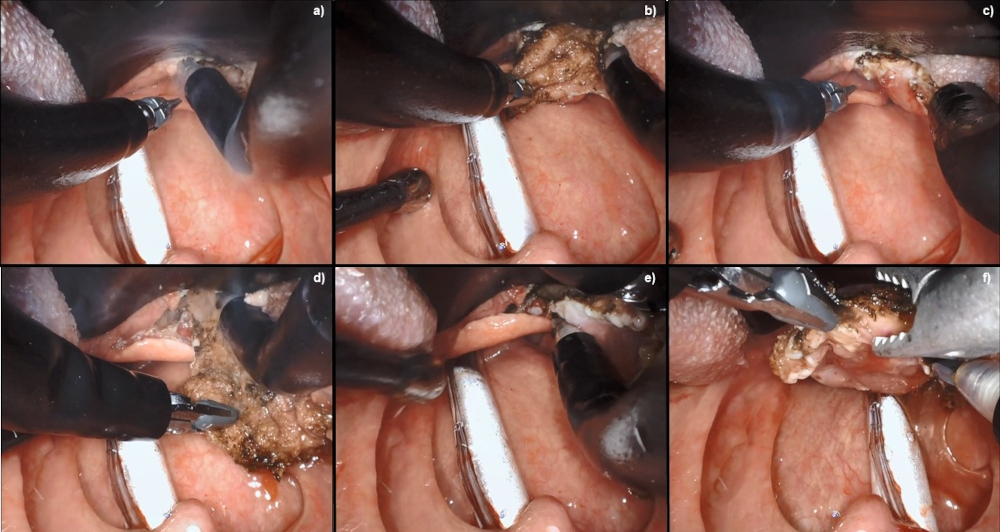

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Robotic wide-field tonsillectomy using the Da Vinci SP robotFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Robotic base of tongue resection using the Da Vinci SP robotFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Robotic base of tongue resection using the Da Vinci SP robotFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].

Preliminary results are promising; however, more data are warranted.[83]Park DA, Lee MJ, Kim SH, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of transoral robotic surgery versus open surgery for oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Apr;46(4 pt a):644-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31627931?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Nguyen AT, Luu M, Mallen-St Clair J, et al. Comparison of survival after transoral robotic surgery vs nonrobotic surgery in patients with early-stage oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Oct 1;6(10):1555-62.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2769670

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32816023?tool=bestpractice.com

TORS is widely thought to be associated with significantly better postoperative functional outcomes, related to speech, swallowing, and need for tracheostomy.

Locally advanced: resectable (T1-T2, N1-N3 disease or T3-T4a, N0-N3 disease, M0 disease)

Patients with resectable locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer can be treated with either surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy, or with concurrent chemoradiotherapy without surgery.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

One randomised study of locally advanced head and neck cancer demonstrated similar local control and survival by either modality.[77]Soo KC, Tan EH, Wee J, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy vs concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III/IV nonmetastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer: a randomised comparison. Br J Cancer. 2005 Aug 8;93(3):279-86.

https://www.nature.com/articles/6602696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16012523?tool=bestpractice.com

Even though the number of patients with oropharyngeal cancers was small, the study corroborated the equal effectiveness of both modalities reported in retrospective studies.[85]Denittis AS, Machtay M, Rosenthal DI, et al. Advanced oropharyngeal cancer treated with surgery and radiotherapy: oncologic outcome and functional assessment. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001 Sep-Oct;22(5):329-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11562884?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Lim YC, Hong HJ, Baek SJ, et al. Combined surgery and postoperative radiotherapy for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Korea: analysis of 110 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Dec;37(12):1099-105.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18722091?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Nguyen NP, Vos P, Smith HJ, et al. Concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007 Jan-Feb;28(1):3-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17162122?tool=bestpractice.com

Survival ranges from 50% to 60% at 3-5 years because of the high rate of distant metastases (20% to 40%).[77]Soo KC, Tan EH, Wee J, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy vs concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III/IV nonmetastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer: a randomised comparison. Br J Cancer. 2005 Aug 8;93(3):279-86.

https://www.nature.com/articles/6602696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16012523?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Denittis AS, Machtay M, Rosenthal DI, et al. Advanced oropharyngeal cancer treated with surgery and radiotherapy: oncologic outcome and functional assessment. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001 Sep-Oct;22(5):329-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11562884?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Lim YC, Hong HJ, Baek SJ, et al. Combined surgery and postoperative radiotherapy for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Korea: analysis of 110 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Dec;37(12):1099-105.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18722091?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Nguyen NP, Vos P, Smith HJ, et al. Concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007 Jan-Feb;28(1):3-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17162122?tool=bestpractice.com

[88]Adelstein DJ, Saxton JP, Lavertu P, et al. A phase III randomized trial comparing concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in resectable stage III and IV squamous cell head and neck cancer: preliminary results. Head Neck. 1997 Oct;19(7):567-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9323144?tool=bestpractice.com

The benefit of adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy has been reported by one meta-analysis for all head and neck cancer anatomical sites. Patients with oropharyngeal cancers had an 8.1% improvement in survival at 5 years.[89]Blanchard P, Baujat B, Holostenco V, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): a comprehensive analysis by tumour site. Radiother Oncol. 2011 Jul;100(1):33-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21684027?tool=bestpractice.com

The increased toxicity of the combined modality may be lessened with modern radiotherapy techniques that decrease the radiotherapy dose to the normal organs. Cisplatin is the preferred first-line chemotherapy agent given concurrently with radiotherapy.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[90]Margalit DN, Anker CJ, Aristophanous M, et al. Radiation therapy for HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: an ASTRO clinical practice guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2024 Sep-Oct;14(5):398-425.

https://www.practicalradonc.org/article/S1879-8500(24)00139-5/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39078350?tool=bestpractice.com

There are many chemotherapy regimens used for concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and it is not known which one is superior. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy can be given without or following induction chemotherapy depending on the medical oncologist's preference.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Some physicians prefer a triple drug induction chemotherapy, even though the risk of toxicity is increased.

Locally advanced: unresectable (T4b, any N, M0 disease)

Patients with locally advanced unresectable head and neck cancer should be treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, if feasible. Randomised studies and one meta-analysis demonstrate better survival and local control with concurrent chemoradiotherapy therapy than with radiotherapy alone.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[91]Budach V, Stuschke M, Budach W, et al. Hyperfractionated accelerated chemoradiation with concurrent fluorouracil-mitomycin is more effective than dose-escalated hyperfractionated accelerated radiation therapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer: final results of the Radiotherapy Cooperative Clinical Trials Group of the German Cancer Society 95-06 Prospective Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Feb 20;23(6):1125-35.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/jco.2005.07.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15718308?tool=bestpractice.com

[92]Bensadoun RJ, Benezery K, Dassonville O, et al. French multicenter phase III randomized study testing concurrent twice-a-day radiotherapy and cisplatin/5-fluorouracil chemotherapy (BiRCF) in unresectable pharyngeal carcinoma: results at 2 years (FNCLCC-GORTEC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Mar 15;64(4):983-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16376489?tool=bestpractice.com

[93]Staar S, Rudat V, Stuetzer H, et al. Intensified hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy limits the additional benefit of simultaneous chemotherapy: results of a multicentric randomized German trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Aug 1;50(5):1161-71. [Erratum in: Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001 Oct 1;51(2):569.]

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11483325?tool=bestpractice.com

[94]Semrau R, Mueller RP, Stuetzer H, et al. Efficacy of intensified hyperfractionated and accelerated radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy with carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil: updated results of a randomized multicentric trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Apr 1;64(5):1308-16.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16464538?tool=bestpractice.com

[95]Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, et al. Final results of the 94-01 French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy Group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant chemoradiotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jan 1;22(1):69-76.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/jco.2004.08.021

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14657228?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Dec 15;91(24):2081-6.

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/91/24/2081/2964959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10601378?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR, et al. Hyperfractionated irradiation with or without concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jun 18;338(25):1798-804.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199806183382503

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9632446?tool=bestpractice.com

[98]Pignon JP, le Maitre A, Maillard E, et al; MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009 Jul;92(1):4-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19446902?tool=bestpractice.com

The most common combinations of chemotherapy were fluorouracil and cisplatin, fluorouracil and carboplatin, and fluorouracil and mitomycin.[91]Budach V, Stuschke M, Budach W, et al. Hyperfractionated accelerated chemoradiation with concurrent fluorouracil-mitomycin is more effective than dose-escalated hyperfractionated accelerated radiation therapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer: final results of the Radiotherapy Cooperative Clinical Trials Group of the German Cancer Society 95-06 Prospective Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Feb 20;23(6):1125-35.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/jco.2005.07.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15718308?tool=bestpractice.com

[92]Bensadoun RJ, Benezery K, Dassonville O, et al. French multicenter phase III randomized study testing concurrent twice-a-day radiotherapy and cisplatin/5-fluorouracil chemotherapy (BiRCF) in unresectable pharyngeal carcinoma: results at 2 years (FNCLCC-GORTEC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Mar 15;64(4):983-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16376489?tool=bestpractice.com

[93]Staar S, Rudat V, Stuetzer H, et al. Intensified hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy limits the additional benefit of simultaneous chemotherapy: results of a multicentric randomized German trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Aug 1;50(5):1161-71. [Erratum in: Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001 Oct 1;51(2):569.]

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11483325?tool=bestpractice.com

[94]Semrau R, Mueller RP, Stuetzer H, et al. Efficacy of intensified hyperfractionated and accelerated radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy with carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil: updated results of a randomized multicentric trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Apr 1;64(5):1308-16.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16464538?tool=bestpractice.com

[95]Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, et al. Final results of the 94-01 French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy Group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant chemoradiotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jan 1;22(1):69-76.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/jco.2004.08.021

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14657228?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Dec 15;91(24):2081-6.

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/91/24/2081/2964959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10601378?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR, et al. Hyperfractionated irradiation with or without concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jun 18;338(25):1798-804.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199806183382503

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9632446?tool=bestpractice.com

[99]Posner MR, Hershock DM, Blajman CR, et al; TAX 324 Study Group. Cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or with docetaxel in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 25;357(17):1705-15.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa070956

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17960013?tool=bestpractice.com

Three-year survival in the concurrent chemoradiotherapy group ranged from 40% to 55%, and locoregional control was 58% to 70% for the combined modality.[92]Bensadoun RJ, Benezery K, Dassonville O, et al. French multicenter phase III randomized study testing concurrent twice-a-day radiotherapy and cisplatin/5-fluorouracil chemotherapy (BiRCF) in unresectable pharyngeal carcinoma: results at 2 years (FNCLCC-GORTEC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Mar 15;64(4):983-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16376489?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Dec 15;91(24):2081-6.

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/91/24/2081/2964959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10601378?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR, et al. Hyperfractionated irradiation with or without concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jun 18;338(25):1798-804.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199806183382503

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9632446?tool=bestpractice.com

However, concurrent chemoradiotherapy is associated with significant grade 3 to 4 toxicity, predominantly mucositis (up to 71%) and haematological adverse effects (up to 32%).[92]Bensadoun RJ, Benezery K, Dassonville O, et al. French multicenter phase III randomized study testing concurrent twice-a-day radiotherapy and cisplatin/5-fluorouracil chemotherapy (BiRCF) in unresectable pharyngeal carcinoma: results at 2 years (FNCLCC-GORTEC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Mar 15;64(4):983-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16376489?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Dec 15;91(24):2081-6.

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/91/24/2081/2964959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10601378?tool=bestpractice.com

It is unclear which chemotherapy regimen or radiotherapy fractionation is optimal. Doses of fluorouracil, cisplatin, and carboplatin vary, although the dose for mitomycin is fixed. Radiotherapy dose ranged from 70 Gy (once a day) to 75 Gy (twice a day).

In summary, the standard of care for patients with unresectable tumours is platinum-based chemotherapy concurrent with radiotherapy. A standard is high-dose cisplatin every 21 days concurrent with radiotherapy, although poor performance status patients may require low-dose weekly cisplatin or carboplatin. Another option is triple-drug induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil, followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy with weekly cisplatin or carboplatin.[99]Posner MR, Hershock DM, Blajman CR, et al; TAX 324 Study Group. Cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or with docetaxel in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 25;357(17):1705-15.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa070956

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17960013?tool=bestpractice.com

[100]Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):92-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12506176?tool=bestpractice.com

The addition of docetaxel to induction cisplatin and fluorouracil resulted in a median survival of 71 months, compared with 30 months for induction cisplatin and fluorouracil followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Local control was also superior in the triple-drug induction arm, although more haematological toxicity was reported. One meta-analysis confirmed the superiority of the triple induction regimen.[101]Blanchard P, Bourhis J, Lacas B, et al; Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer, Induction Project, Collaborative Group. Taxane-cisplatin-fluorouracil as induction chemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancers: an individual patient data meta-analysis of the meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer group. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Aug 10;31(23):2854-60.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/jco.2012.47.7802

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23835714?tool=bestpractice.com

However, the optimal chemoradiotherapy regimen remains unclear, as these regimens have not been directly compared.

Distant metastases at presentation (any T, any N, M1 disease)

Patients with distant metastases should be treated with targeted therapy if amenable, and chemotherapy if not amenable to targeted therapy. Consideration should be given to combination therapy of immunotherapy plus platinum-based chemotherapy in the setting of metastatic head and neck cancer, as this has been shown to provide a survival benefit.[78]Xu Q, Huang S, Yang K. Combination immunochemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2023 Jun 13;13(6):e069047.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/6/e069047

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37311638?tool=bestpractice.com

Conventional chemotherapy is usually a platinum agent combined with fluorouracil. As a result of the KEYNOTE-048 trial, chemoimmunotherapy is now the standard of care in recurrent or metastatic unresectable head and neck cancers. In patients with metastatic disease with high PD-L1 staining (CPS score >1), immunotherapy alone can also be considered as the first-line treatment.[102]Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019 Nov 23;394(10212):1915-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31679945?tool=bestpractice.com

The immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab as a single agent or in combination with platinum chemotherapy and fluorouracil is the preferred first-line treatment in this patient group.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer management

Early-stage (T0-T2, N0 or N1, M0 disease)

Patients may be treated with either upfront surgery or radiotherapy.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Even though no randomised study has compared the two modalities, retrospective studies reported similar local control and survival rates, ranging from 80% to 90%.[59]Roosli C, Tschudi DC, Studer G, et al. Outcome of patients after treatment for a squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Laryngoscope. 2009 Mar;119(3):534-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19235752?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Cosmidis A, Rame JP, Dassonville O, et al; Groupement d'Etudes des Tumeurs de la Tête et du Cou (GETTEC). T1-T2 N0 oropharyngeal cancers treated with surgery alone: a GETTEC study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004 May;261(5):276-81.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14551793?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: surgery, radiotherapy, or both. Cancer. 2002 Jun 1;94(11):2967-80.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.10567

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12115386?tool=bestpractice.com

The choice of treatment modality is dependent on size of the primary tumour and location within the oropharynx. Tumours at or approaching the midline (i.e., tumours in the base of the tongue, posterior pharyngeal wall, soft palate, and tonsil invading the tongue base) are at risk of contralateral metastasis and warrant bilateral treatment.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Historically, surgery for oropharyngeal cancer required splitting of the mandible or a pharyngotomy to provide access to the inferior tonsillar fossa or base of tongue.

TORS is an innovative technique for early-stage oropharyngeal cancer that allows sparing of the mandible compared with conventional surgery.[82]Parikh A, Lin D, Goyal N. Clinical outcomes of transoral robotic-assisted surgery for the management of head and neck cancer. Robot Surg. 2023 Feb 20;2(2015):95-105.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/RSRR.S70549

Preliminary results are promising; however, more data are warranted.[83]Park DA, Lee MJ, Kim SH, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of transoral robotic surgery versus open surgery for oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Apr;46(4 pt a):644-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31627931?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Nguyen AT, Luu M, Mallen-St Clair J, et al. Comparison of survival after transoral robotic surgery vs nonrobotic surgery in patients with early-stage oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Oct 1;6(10):1555-62.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2769670

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32816023?tool=bestpractice.com

TORS is widely thought to be associated with significantly better postoperative functional outcomes, related to speech, swallowing, and need for tracheostomy.

With HPV-positive patients presenting with better functional status and having better survival, surgery-first approaches are often considered with the idea that radiotherapy, as a treatment modality, may be reserved for a future recurrence. In addition, these patients have longer to live with the late effects of radiotherapy.

Locally advanced: resectable (T3/T4 or presence of nodal disease beyond single lymph node <3 cm)

Patients with resectable locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer can be treated with either surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy, or with concurrent chemoradiotherapy without surgery. One randomised study of locally advanced head and neck cancer demonstrated similar local control and survival by either modality.[77]Soo KC, Tan EH, Wee J, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy vs concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III/IV nonmetastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer: a randomised comparison. Br J Cancer. 2005 Aug 8;93(3):279-86.

https://www.nature.com/articles/6602696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16012523?tool=bestpractice.com

Even though the number of patients with oropharyngeal cancers was small, the study corroborated the equal effectiveness of both modalities reported in retrospective studies.[85]Denittis AS, Machtay M, Rosenthal DI, et al. Advanced oropharyngeal cancer treated with surgery and radiotherapy: oncologic outcome and functional assessment. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001 Sep-Oct;22(5):329-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11562884?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Lim YC, Hong HJ, Baek SJ, et al. Combined surgery and postoperative radiotherapy for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Korea: analysis of 110 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Dec;37(12):1099-105.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18722091?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Nguyen NP, Vos P, Smith HJ, et al. Concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007 Jan-Feb;28(1):3-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17162122?tool=bestpractice.com

Survival ranges from 50% to 60% at 3-5 years because of the high rate of distant metastases (20% to 40%).[77]Soo KC, Tan EH, Wee J, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy vs concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III/IV nonmetastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer: a randomised comparison. Br J Cancer. 2005 Aug 8;93(3):279-86.

https://www.nature.com/articles/6602696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16012523?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Denittis AS, Machtay M, Rosenthal DI, et al. Advanced oropharyngeal cancer treated with surgery and radiotherapy: oncologic outcome and functional assessment. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001 Sep-Oct;22(5):329-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11562884?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Lim YC, Hong HJ, Baek SJ, et al. Combined surgery and postoperative radiotherapy for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Korea: analysis of 110 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Dec;37(12):1099-105.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18722091?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Nguyen NP, Vos P, Smith HJ, et al. Concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007 Jan-Feb;28(1):3-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17162122?tool=bestpractice.com

[88]Adelstein DJ, Saxton JP, Lavertu P, et al. A phase III randomized trial comparing concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in resectable stage III and IV squamous cell head and neck cancer: preliminary results. Head Neck. 1997 Oct;19(7):567-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9323144?tool=bestpractice.com

The benefit of adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy has been reported by one meta-analysis for all head and neck cancer anatomical sites. Patients with oropharyngeal cancers had an 8.1% improvement in survival at 5 years.[89]Blanchard P, Baujat B, Holostenco V, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): a comprehensive analysis by tumour site. Radiother Oncol. 2011 Jul;100(1):33-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21684027?tool=bestpractice.com

The increased toxicity of the combined modality may be lessened with modern radiotherapy techniques that decrease the radiotherapy dose to the normal organs. Cisplatin is the preferred first-line chemotherapy agent given concurrently with radiotherapy.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[90]Margalit DN, Anker CJ, Aristophanous M, et al. Radiation therapy for HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: an ASTRO clinical practice guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2024 Sep-Oct;14(5):398-425.

https://www.practicalradonc.org/article/S1879-8500(24)00139-5/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39078350?tool=bestpractice.com

There are many chemotherapy regimens used for concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and it is not known which one is superior. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy can be given without or following induction chemotherapy depending on the medical oncologist's preference.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Some physicians prefer a triple drug induction chemotherapy, even though the risk of toxicity is increased.

Evidence from randomised controlled trials that enrolled patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer demonstrated that cetuximab plus radiotherapy was inferior to cisplatin plus radiotherapy (in terms of overall survival).[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[103]Gillison ML, Trotti AM, Harris J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab or cisplatin in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018 Nov 15;393(10166):40-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30449625?tool=bestpractice.com

[104]Mehanna H, Robinson M, Hartley A, et al. Radiotherapy plus cisplatin or cetuximab in low-risk human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (De-ESCALaTE HPV): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018 Nov 15;393(10166):51-60.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)32752-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30449623?tool=bestpractice.com

Thus, cetuximab plus radiotherapy is no longer recommended for this patient group.

Distant metastases at presentation (any T, any N, M1 disease)

Patients with distant metastases should be treated with targeted therapy if amenable, and chemotherapy if not amenable to targeted therapy. Consideration should be given to combination therapy of immunotherapy plus platinum-based chemotherapy in the setting of metastatic head and neck cancer, as this has been shown to provide a survival benefit.[78]Xu Q, Huang S, Yang K. Combination immunochemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2023 Jun 13;13(6):e069047.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/6/e069047

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37311638?tool=bestpractice.com

Conventional chemotherapy is usually a platinum agent combined with fluorouracil. As a result of the KEYNOTE-048 trial, chemoimmunotherapy is now the standard of care in recurrent or metastatic unresectable head and neck cancers. In patients with metastatic disease with high PD-L1 staining (CPS score >1), immunotherapy alone can also be considered as the first-line treatment.[102]Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019 Nov 23;394(10212):1915-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31679945?tool=bestpractice.com

The immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab as a single agent or in combination with platinum chemotherapy and fluorouracil is the preferred first-line treatment in this patient group.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Patients with recurrent disease

In patients with recurrent disease after previous local therapy without any evidence of distant metastases, salvage with surgery, radiotherapy, or chemoradiotherapy may be considered on an individual basis, while bearing in mind treatment toxicity.[105]Bumpous JM. Surgical salvage of cancer of the oropharynx after chemoradiation. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009 Mar;11(2):151-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19216847?tool=bestpractice.com

[106]Watkins JM, Shirai KS, Wahlquist AE, et al. Toxicity and survival outcomes of hyperfractionated split-course reirradiation and daily concurrent chemotherapy in locoregionally recurrent, previously irradiated head and neck cancers. Head Neck. 2009 Apr;31(4):493-502.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19156831?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with recurrent disease after definitive treatment should undergo salvage treatment with immunotherapy (with or without chemotherapy) if they are not a candidate for definitive surgery or chemoradiotherapy. Consideration should be given to combination therapy of immunotherapy plus platinum-based chemotherapy in the setting of recurrent head and neck cancer, as this has been shown to provide a survival benefit.[78]Xu Q, Huang S, Yang K. Combination immunochemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2023 Jun 13;13(6):e069047.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/6/e069047

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37311638?tool=bestpractice.com

The immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab is approved in the US as first-line treatment of metastatic or unresectable, recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in adults in combination with platinum chemotherapy and fluorouracil, or as a single agent in those whose tumours express PD-L1 with a combined positive score (CPS) ≥1. It is also approved in the US as a single agent for the treatment of patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with disease progression, on or after platinum-containing chemotherapy. The NCCN supports these recommendations.[2]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: head and neck cancers [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

In Europe, pembrolizumab is approved, as a single agent or in combination with platinum chemotherapy and fluorouracil, as first-line treatment of metastatic or unresectable, recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in adults whose tumours express PD-L1 with a CPS ≥1. It is also approved in Europe as a single agent for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in adults whose tumours express PD-L1, with a ≥50% tumour proportion score and progressing on, or after, platinum chemotherapy. The approvals were based on results from the KEYNOTE-048 trial.[102]Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019 Nov 23;394(10212):1915-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31679945?tool=bestpractice.com

NICE also recommends pembrolizumab as an option for untreated metastatic or unresectable recurrent head and neck squamous cell cancer in adults whose tumours express PD‑L1 with a CPS ≥1 only if pembrolizumab is given as a monotherapy, it is stopped at 2 years of uninterrupted treatment or earlier if disease progresses, and the company provides pembrolizumab according to the commercial agreement.[107]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pembrolizumab for untreated metastatic or unresectable recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nov 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta661

NICE recommends nivolumab as an option for treating recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in patients in whom disease has progressed within 6 months of receiving platinum‑based chemotherapy.[108]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nivolumab for treating recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck after platinum-based chemotherapy. Oct 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta736/chapter/1-Recommendations

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transhyoid open approach to a large base of tongue tumourFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transhyoid open approach to a large base of tongue tumourFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Robotic base of tongue resection using the Da Vinci SP robotFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Robotic base of tongue resection using the Da Vinci SP robotFrom the collection of Dr Linda X. Yin; used with permission [Citation ends].