Aetiology

Mastitis may occur with or without infection. Infectious mastitis and breast abscesses are usually caused by bacteria colonising the skin. Cases due to Staphylococcus aureus are by far the most common, followed by those due to coagulase-negative staphylococci.[1][5] Methicillin-resistant S aureus is a growing problem and has been increasingly found in cases of mastitis and breast abscesses.[10][11]

Breast infections may sometimes be polymicrobial (up to 40% of abscesses), with isolation of aerobes (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, Corynebacterium, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas) as well as anaerobes (Peptostreptococcus, Propionibacterium, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Eubacterium, Clostridium, Fusobacterium, and Veillonella).[12][13][14] A study of primary and recurrent breast abscesses showed that smokers were more likely to have anaerobes recovered (isolated in 15% of patients).[15]

More unusual pathogens may include Bartonella henselae (the agent of cat scratch disease), mycobacteria (TB and atypical mycobacteria), Actinomyces, Brucella, fungi (Candida and Cryptococcus), parasites, and maggot infestation. Unusual breast infections may be the initial presentation of HIV infection.[16][17]

Non-infectious mastitis may result from underlying duct ectasia (peri-ductal mastitis or plasma cell mastitis) and infrequently foreign material (e.g., nipple piercing, breast implant, or silicone).[18][19] Granulomatous (lobular) mastitis is a benign disease of unknown aetiology.[9]

Pathophysiology

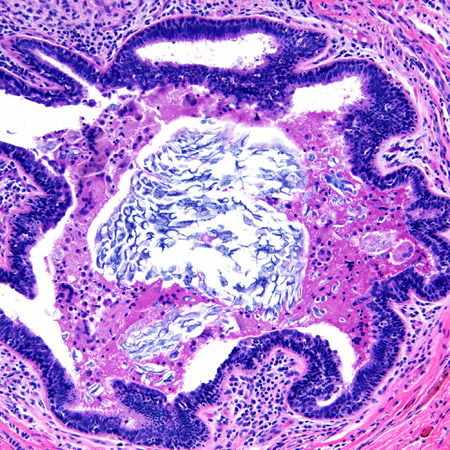

In lactational mastitis, milk stasis or milk overproduction, coupled with infection from bacteria entering the breast via a traumatised nipple (e.g., cracked or fissured) and/or from the infant's mouth, can lead to mastitis.[1] Transient breast enlargement from maternal hormones in neonates makes them vulnerable to mastitis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lactational mastitis: microscopy image showing hyper-secretory glands associated with inflammationFrom the collection of Liron Pantanowitz, MD, Tufts University School of Medicine, MA [Citation ends].

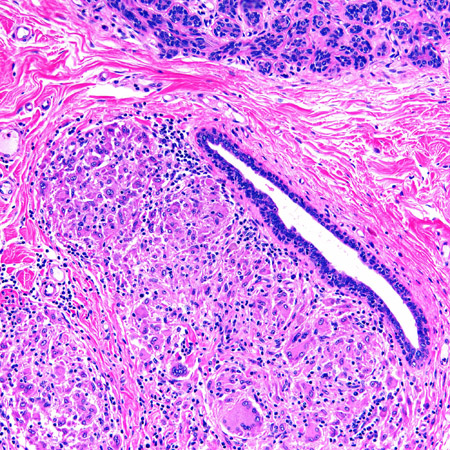

In duct ectasia (dilated ducts associated with inflammation), the mammary duct-associated inflammatory disease sequence involves squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts. This causes blockage (obstructive mastopathy) with peri-ductal inflammation and possible duct rupture.[5] Inflamed ducts are prone to bacterial infection. Left untreated, mastitis may cause tissue destruction resulting in an abscess.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Duct ectasia with a central calcified keratin plug and associated giant cell inflammatory responseFrom the collection of Liron Pantanowitz, MD, Tufts University School of Medicine, MA [Citation ends].

Non-puerperal abscesses unrelated to breastfeeding may be sub-areolar or peripheral. Sub-areolar mastitis is thought to be due to damage of the sub-areolar ducts, which then become infected; smoking is suspected to be a significant predisposing factor. A lactational abscess is often peripheral and often due to the cracking of the nipple, which allows entrance of bacteria that can then infect milk-filled ducts.[20]

An abscess may also occur without apparent preceding mastitis. Rupture of an abscess can lead to a draining sinus with a resulting fistula.

In tubercular mastitis, mycobacterial bacilli can enter the breast from:

Direct inoculation (primary infection) via a nipple abrasion

Distant portals (secondary infection), such as lymphatic spread, haematogenous (miliary) dissemination, or contiguous spread (e.g., empyema necessitans).

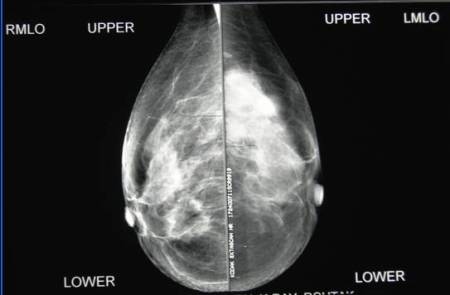

Tuberculosis (TB) of the breast may present with a nodular, diffuse, or sclerosing reaction. The most common presentation is a painless lump with or without a sinus tract. Most cases of tuberculous mastitis are secondary, and infection occurs via contiguous spread from lymphatics (most commonly axillary, followed by cervical or mediastinal nodes) or less commonly from the pleura or chest wall or via the haematogenous route. Primary TB of the breast is rare. In some cases tubercular mastitis may be mistaken for breast carcinoma.[6][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tubercular mastitis: mammogram showing a mass lesion in the upper outer quadrantAdapted from the Internet J Surgery (2007); used with permission [Citation ends].

Necrotising granulomas are the histopathological hallmark of TB infection.

In idiopathic granulomatous mastitis, non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation is centred on lobules that clinically may result in a painless mass. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Microscopy image of non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation in the breastFrom the collection of Liron Pantanowitz, MD, Tufts University School of Medicine, MA [Citation ends].

Classification

Types of mastitis and breast abscess[1]

Lactational mastitis: breast inflammation with or without infection associated with breastfeeding.

Non-lactational mastitis: breast inflammation with or without infection in the non-lactating breast.

Non-infectious mastitis: breast inflammation due to a non-infectious and/or idiopathic aetiology.

Subclinical mastitis: raised interleukin and sodium/potassium ratio in breast milk in the absence of clinical mastitis in the lactating breast.

Breast abscess: localised breast infection with a walled-off collection of pus.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer