Recommendations

Urgent

Time is brain" - if you suspect a stroke, work rapidly through the initial assessment and aim for quick access to computed tomography (CT) scan.

CT enables quick differentiation between ischaemic stroke and spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) which must be done before reversing anticoagulation in anticoagulation-induced ICH, and before starting thrombolysis in ischaemic stroke.[30][55] Both are critical and urgent interventions.

Suspect stroke in a patient with sudden onset of focal neurological symptoms:[56]

Unilateral weakness or paralysis in the face, arm, or leg

Unilateral sensory loss

Dysarthria or expressive or receptive dysphasia

Vision problems (e.g., hemianopia)

Headache (sudden severe and unusual headache)

Difficulty with coordination and gait

Vertigo or loss of balance, especially with the above signs.

Suspect subarachnoid haemorrhage in anyone presenting with sudden severe (thunderclap) headache, stiff neck, photophobia and blurred vision.[56] See Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Use a validated tool to aid diagnosis in people with suspected stroke:

In the emergency department: use the ROSIER scale (Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room) in people with suspected stroke.[55]

In the community: use FAST (Face Arm Speech Test) to screen people with sudden onset of neurological symptoms for stroke.[55]

Exclude hypoglycaemia (a stroke mimic) as the cause of sudden neurological symptoms.[55]

Request brain imaging as soon as possible (at most within 1 hour of arrival at hospital).[30]

Once you have managed any airway, breathing, and circulatory insufficiencies requiring urgent intervention and following your initial assessment, prioritise rapid:

Key Recommendations

Obtain a brief history (from witnesses or next of kin) followed by an abbreviated neurological examination using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.[30] [ NIH Stroke Score Opens in new window ]

This tool measures the degree of neurological deficit. Higher scores indicate a more severe stroke.

Assess the patient’s level of consciousness using the Glasgow Coma Scale. [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Exclude mimics such as seizures in people with an altered level of consciousness/coma. See Differentials section.

Request brain imaging as soon as possible (at most within 1 hour of arrival at hospital).[30]

Order in all patients:

Serum electrolytes

Serum urea and creatinine

Liver function tests

Full blood count

Clotting screen

ECG[23]

Consider a serum toxicology screen if you suspect use of toxic substances.[23]

Suspect stroke in a patient with sudden onset focal neurological symptoms:[56]

Unilateral weakness or paralysis in the face, arm, or leg

Complete or partial loss of muscle strength in face, arm, and/or leg is among the most common presentations of stroke.

As with most stroke signs and symptoms, bilateral involvement is uncommon and may reflect alternative aetiology (but can be seen with bilateral brainstem or spinal infarcts).

Sensory loss (numbness)

Patients often describe sensory loss and paraesthesias as “numbness”, “tingling” or “pins and needles”.

Sensory inattention is a useful cortical sign, localising to the contralateral parietal region.

Cortical sensory loss usually impairs fine sensory processing abilities such as two-point discrimination, graphaesthesia, or stereognosis.

Thalamic haemorrhages can present with sensory loss and pseudoathetosis.

Dysarthria or expressive or receptive dysphasia

Dysarthria may accompany facial weakness or cerebellar dysfunction.

Impairment in any language function (fluency, naming, repetition, comprehension) is a sign of dominant hemispheric stroke.

Visual disturbance

Homonymous hemianopia (i.e., visual field loss on the left or right side of the vertical midline on the same side of both eyes) may result from haemorrhage in the visual pathways, including the occipital lobe.

Diplopia may result from brain stem haemorrhage.

Spontaneous ICH can often cause photophobia.

Headache

Usually of insidious onset and gradually increasing intensity in ICH.

More common in ICH than in ischaemic stroke, but the absence of headache does not rule out ICH.

Thunderclap headache (defined as sudden, severe headache that reaches maximum intensity upon onset) is characteristic of subarachnoid haemorrhage. See Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Difficulty with coordination and altered gait

In the absence of muscle weakness, impaired coordination points to haemorrhage involving the cerebellum or its connections with the rest of the brain.

Other symptoms include:

Vertigo

Often reported as a spinning sensation; may also be described as feeling like being “on a ship in choppy seas”.

Typically seen in cerebellar or brainstem haemorrhage.

Nausea/vomiting

May either be due to posterior circulation haemorrhage or reflect increased intracranial pressure.

With cerebellar haemorrhage, nausea and vomiting may be the only presenting symptoms, with an unremarkable neurological examination except for gait ataxia.

Altered level of consciousness/coma

Urgently diagnose (rule out haemorrhage) and manage (breathing and airway protection) any patient with altered consciousness or in a coma.

Reduced alertness may accompany very large hemispheric haemorrhages or posterior fossa haemorrhages.

Coma is more common in people with brain stem haemorrhage.

Exclude conditions mimicking stroke (e.g., seizures).

Confusion

Common especially in older people with previous strokes or cognitive dysfunction.

Differentiate aphasia from confusion; aphasia is a specific sign of dominant hemisphere injury.

Gaze paresis

Often horizontal and unidirectional.

About 11% of all patients presenting to hospital in the UK with acute stroke have spontaneous ICH as the cause.[30]

Suspect subarachnoid haemorrhage in anyone presenting with sudden severe (thunderclap) headache, stiff neck, photophobia, and blurred vision.[56] See Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Initial assessment

The goal of the initial assessment is to recognise a stroke quickly - “time is brain.

In the emergency department

Use the ROSIER scale (Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room) in patients with suspected stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) to establish the diagnosis rapidly.[55]

Score -1 point for each feature (clinical history):

Loss of consciousness or syncope

Seizure activity

Score +1 point for each feature (neurological history):

Asymmetrical face weakness

Asymmetrical arm weakness

Asymmetrical leg weakness

Speech disturbance

Visual field defect

A score >0: stroke likely; a score ≤0: stroke unlikely (but not excluded).

In the community

Use a validated tool such as FAST (Face Arm Speech Test) to screen people with sudden onset of neurological symptoms for a diagnosis of stroke:[55]

Score 1 point for each feature:

Face weakness

Arm (or leg) weakness

Speech disturbance

Suspect stroke if score > 0; refer for emergency medical care in hospital (by 999 ambulance in the UK).

Practical tip

Be aware that the patient may have ongoing focal neurological deficits (such as visual disturbance or balance problems) despite a negative FAST. Continue to manage them as you would someone with acute stroke.[30]

Evidence: FAST and ROSIER scales to identify stroke

Despite limited evidence, guidelines recommend using validated screening tools to expedite access to specialist care for patients with stroke or TIA in the pre-hospital setting. There are fewer guideline recommendations on the use of these tools in the emergency department setting.[30][55][59]

[  ]

]

Pre-hospital setting

The 2023 National Clinical Guideline for Stroke for the UK and Ireland recommends the Face Arms Speech Time (FAST) test in the pre-hospital phase, but states that further evidence is required before 'recognition of stroke in the emergency room' (ROSIER) can be recommended to screen for non-FAST symptoms in the pre-hospital phase.[30]

The recommendation for use of FAST is based on working party consensus and the results of a single diagnostic accuracy study comparing ambulance paramedics using FAST versus primary care doctor versus emergency department (ED) referrals for 487 people with suspected stroke to a stroke unit.[60]

The study found ambulance paramedics' stroke diagnosis using FAST gave a positive predictive value (PPV; i.e., the proportion with a positive test who in reality actually have the condition or characteristic) of 78% (95% CI 72% to 84%).[60]

FAST may not identify some people with symptoms of stroke (e.g., sudden onset visual disturbance, lateralising cerebellar dysfunction).

Community-based clinicians should continue to treat a person as having a suspected stroke if they are suspicious of the diagnosis despite a negative FAST test.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) stroke guideline from 2008 (not changed in the 2022 update) also recommends using a validated tool, such as FAST, outside hospital, citing evidence from the same diagnostic accuracy study.[55][60]

One 2017 European Academy of Neurology and the European Stroke Organisation consensus statement for pre-hospital management of stroke makes no recommendation for a specific scale, but instead states:

To use a simple pre-hospital stroke scale (no specific one recommended), despite the lack of evidence. In their view, benefit would outweigh possible harm and minimal resource use.

To be aware that the scales (currently available at the time of this guidance) are not sensitive enough to detect posterior circulation stroke.

Emergency department setting

NICE recommends using a validated tool, such as ROSIER, in the ED.[55]

This recommendation is underpinned by a validation study for the ROSIER tool including 343 patients with suspected stroke in the ED in the development phase and 173 in the validation phase. In this study, ROSIER showed a PPV of 90% (95% CI 85% to 95%) when used by ED clinicians.[61]

The National Clinical Guideline for Stroke for the UK and Ireland makes no specific recommendation on the use of ROSIER to screen for stroke in the hospital ED setting.[30]

Take a careful history. Establish contact with witnesses or the patient’s next of kin, not only for an accurate history but also to seek consent from next of kin for invasive tests or treatments, if these are needed.

Determine the time of stroke onset because this is the main factor that will determine some stroke interventions.

If the onset was unwitnessed, the time of symptom onset is when the patient was last seen well.[55]

Ask about onset (sudden or gradual), duration, intensity, and fluctuation of symptoms.

The symptoms and signs of ICH often start suddenly and progress over several minutes.[23]

Symptoms of ischaemic stroke may, in contrast, be maximal at onset, particularly in embolic infarction. See Ischaemic stroke.

Symptoms that spontaneously improve or resolve suggest ischaemia rather than haemorrhage.

Ask specifically about relevant past medical history that will influence management. This includes:[23]

Vascular risk factors: history of stroke or ICH, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or smoking

Medications: anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, antihypertensives, stimulants (including diet pills), and sympathomimetic drugs

Recent trauma or surgery: carotid endarterectomy or carotid stenting

ICH may be related to hyperperfusion after such procedures.

Dementia: associated with amyloid angiopathy

Seizures

Liver disease, cancer, and haematological disorders: may be associated with coagulopathy.

Practical tip

The time of onset is not always easy to determine, particularly if the onset was not witnessed and the patient is unable to communicate, symptoms are mild and not immediately noticeable, or if there is a stuttering or fluctuating course.

Ask about common risk factors for spontaneous ICH:

Exclude stroke mimics such as hypoglycaemia, seizures, brain tumours, sepsis, or migraine to ensure timely treatment. See Differentials.

Bear in mind the key clinical features that may help distinguish between stroke and mimics (e.g., seizures, hypoglycaemia) at the initial bedside assessment:

Suggestive of mimic | Suggestive of stroke |

|---|---|

|

Perform a general physical examination focusing on the head, heart, lungs, abdomen, and extremities.[23]

Assess the patient’s level of consciousness using the Glasgow Coma Scale. [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

ICH is more often associated with reduced level of consciousness than ischaemic stroke.[23]

Perform an abbreviated neurological examination using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).[23] [ NIH Stroke Score Opens in new window ]

This tool measures the degree of neurological deficits. Higher scores indicate a more severe stroke.

People with ICH more often have depressed consciousness on initial presentation than patients with ischaemic stroke, reducing the utility of the NIHSS.

The most common findings on neurological examination are:

Altered level of consciousness

Partial or total loss of strength in upper and/or lower extremities (usually unilateral)

Fluent or non-fluent language dysfunction

Sensory loss in upper and/or lower extremities (associated with sensory neglect if non-dominant hemisphere stroke)

Gaze deviation (towards the damaged sphere)

Gaze paresis (often horizontal and unidirectional)

Visual field loss

Dysarthria

Difficulty with fine motor coordination and gait.

Practical tip

Brainstem and cerebellar haemorrhages are more frequently associated with altered levels of consciousness, coma, and vomiting than ischaemic strokes.

CT head

Request brain imaging as soon as possible (at most within 1 hour of arrival at hospital).[30]

Practical tip

Aim to take a collateral history from relatives regarding medications/past medical history while the patient is in the CT scanner.

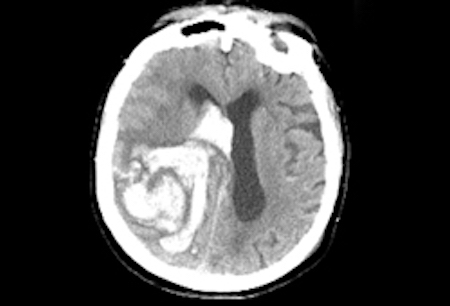

Confirm ICH by the presence of hyperattenuation (brightness) suggesting acute blood, often with surrounding hypoattenuation (darkness) due to oedema.[63][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intracranial haemorrhage on CT scanMassachusetts General Hospital personal case files; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use the CT scan to differentiate between ischaemic stroke and ICH; this must be done before reversing anticoagulation in anticoagulation-induced ICH and before starting thrombolysis in ischaemic stroke.[30][55] See Ischaemic stroke.

Only healthcare professionals with appropriate training should interpret acute stroke imaging for thrombolysis or thrombectomy decisions.[30]

Patients with intracerebral haemorrhage in whom the haemorrhage location or other imaging features suggest cerebral venous thrombosis should be investigated urgently with a CT or magnetic resonance venogram.[30]

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) head

Early non-invasive cerebral angiography (CTA/MRA within 48 hours of onset) should be considered for all patients with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage aged 18-70 years who were independent, without a history of cancer, not taking an anticoagulant, except if they are aged more than 45 years with hypertension and the haemorrhage is in the basal ganglia, thalamus, or posterior fossa.[30] If this early CTA/MRA is normal or inconclusive, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/MRA with susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) should be considered at 3 months. Early CTA/MRA and MRI/MRA at 3 months may also be considered in patients not meeting these criteria where the probability of a macrovascular cause is felt to justify further investigation.

Intra-arterial cerebral angiography

The DIAGRAM score (or its components: age; intracerebral haemorrhage location; CTA result where available; and the presence of white matter low attenuation [leukoaraiosis] on the admission non-contrast CT) should be considered to determine the likelihood of an underlying macrovascular cause and the potential benefit of intra-arterial cerebral angiography.[30]

Blood tests

While CT transport is being organised, insert an intravenous catheter with blood sampling.[30] Order in all patients:

Serum glucose

Serum electrolytes

To exclude electrolyte disturbance (e.g., hyponatraemia) as a cause for neurological signs.

Serum urea and creatinine

To exclude renal failure because it may be a potential contraindication to some stroke interventions.

Liver function tests

To exclude liver dysfunction as a cause of haemorrhage.

Full blood count

To exclude thrombocytopenia as a cause of haemorrhage.

Clotting screen

To exclude coagulopathy as a cause of haemorrhage. Check international normalised ratio (INR) or factor Xa levels, if available.

Consider a serum toxicology screen if you suspect use of toxic substances.

Cocaine and other sympathomimetic drugs of misuse are associated with ICH, especially in younger people.[23]

ECG

Perform an ECG in all patients to assess for active coronary ischaemia or prior cardiac injury; ECG abnormalities can indicate concomitant myocardial injury.[23]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer