Details

Excess weight is responsible for an estimated 500,000 deaths per year in the US.[1] In England and Scotland, an estimated 23% of all deaths are attributed to overweight or obesity.[2] The incidence of class III obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 40 or above) is increasing at a rapid rate, and this has resulted in an increase in bariatric operations worldwide. Bariatric surgery (also referred to as metabolic surgery) has been shown to substantially lower all-cause mortality rates among adults with obesity, compared with non-surgical obesity management.[3] Studies demonstrate that children and adolescents with class III obesity benefit from weight loss surgery.[4] The mechanism of action of bariatric surgery for obesity is not fully understood but is believed to include gastric volume restriction, malabsorption, and hormonal changes.[5][6]

Recommendations for the BMI threshold for bariatric surgery differ among guidelines.[7][8][9][10] The American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders recommend bariatric surgery for individuals who have a BMI of ≥35 kg/m², regardless of comorbidities, or for individuals with a BMI between 30.0 and 34.9 kg/m² who do not achieve durable weight loss and management of comorbidities despite optimal non-surgical therapy.[8] Bariatric surgery is also a treatment option for patients with type 2 diabetes and a BMI >30 kg/m² who do not achieve durable weight loss and management of comorbidities despite optimal non-surgical therapy.[11][8] In Asian individuals the BMI threshold is lower due to differences in body composition and cardiometabolic risk.[11]

After bariatric surgery, patients may present to clinics, emergency departments, or a hospital other than the one where they had the operation. Thus, knowledge of common complications is necessary.[12] The abdomen with central adiposity may be difficult to examine and can mask typical signs of sepsis. Careful attention to vital signs, examination findings, and any deviation from expected post-operative course is essential.

The most commonly performed operations include:[8]

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Sleeve gastrectomy.

Although these may be performed through open or laparoscopic techniques, the majority of bariatric surgery is performed laparoscopically.[8][10]

Other operations include:[13]

Emerging operations

One-anastomosis gastric bypass

Single anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve

Less common operations

Adjustable gastric banding, e.g., the Lap-Band

Biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch.

Bariatric surgery requires specialist anesthesiology expertise.[14]

Preparation for surgery includes preoperative weight loss, glycaemic control, and medication reconciliation. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathways have been developed for bariatric surgery in order to standardise these perioperative interventions.[15][16] One aspect of ERAS and patient preparation is the shared decision-making regarding the need and choice of surgery. The Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) risk-benefit calculator estimates a patient’s chance of postoperative complications, remission of weight-related comorbidities, and postoperative weight change, and may be useful to provide a context for preoperative discussion.[17] MBSAQIP: MBSAQIP Bariatric Surgical Risk/Benefit Calculator Opens in new window

Weight loss after bariatric surgery is difficult to predict, as it may be affected by predisposing genetic factors, preoperative weight, and adherence to planned post-operative diet and activity level.[18][19] Post-surgical weight loss is typically measured as percentage of initial excess body weight lost, with excess weight calculated as initial body weight minus ideal body weight. One systematic review of bariatric surgery reported long-term (2 years or more) excess weight loss of 49% for adjustable gastric band, 63% for gastric bypass, and 73% for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch.[20] Following sleeve gastrectomy, mean percentage excess weight loss of 58.4%, 59.5%, 56.6%, 56.4%, and 62.5% has been reported at 5, 6, 7, 8, and 11 years, respectively.[21] The MBSAQIP risk-benefit calculator can provide guidance for postoperative weight loss expectations.[17] MBSAQIP: MBSAQIP Bariatric Surgical Risk/Benefit Calculator Opens in new window

In addition to weight loss, bariatric surgery has a profound impact on the resolution of type 2 diabetes mellitus and other obesity related illness, more so than can be achieved by medical measures.[20][22][23][24][25]

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has historically been the most common bariatric operation worldwide. Although it lost much of its pre-eminence to the adjustable gastric band in the 2000s and more recently to the sleeve gastrectomy, it is now the second most common type of bariatric surgery.[26][27] One large meta-analysis of randomised trials reported a mortality rate of <0.1% for gastric bypass.[28]

Bypass may be performed through either laparoscopic technique or open surgical technique. The laparoscopic technique uses 5 to 7 abdominal access incisions 5 mm to 15 mm in length, whereas the open technique generally requires a vertical midline incision. The laparoscopic approach involves less postoperative pain, faster recovery, and fewer wound-related complications.[29]

A surgical stapler is used to divide the stomach into 2 sections. The upper section is typically referred to as the gastric pouch and is 15 mL to 30 mL in volume, based on the lesser curvature of the stomach (right side). It excludes the gastric fundus.

Using a stapler that both staples and divides tissue, the jejunum is transected 20 cm to 100 cm from its origin at the ligament of Treitz. The proximal end is connected 75 cm to 150 cm 'downstream' from the distal segment - or 'Roux limb'. The Roux limb is connected to the gastric pouch, thus creating a Y-shaped intestinal anatomy.

The distal stomach is completely excluded from the alimentary path. Its secretions, along with those from the liver and pancreas, drain through the biliopancreatic limb (20 cm to 100 cm long).

Food passes from the oesophagus into the gastric pouch, before passing through the proximal anastomosis to enter the Roux limb or alimentary limb (75 cm to 150 cm long). At the distal anastomosis, the ingested food joins the digestive secretions in the common channel (150 cm to 400 cm long).

Weight loss and metabolic improvements result through several different mechanisms, including gastric volume restriction, mild malabsorption, and hormonal effects.[5][6]

The gastric remnant and biliopancreatic limb are inaccessible during standard upper endoscopy or colonoscopy, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography cannot be performed.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass diagramCopyright ©2008 Daniel M. Herron, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Early complications are considered to be those that occur within 30 days of surgery. Early complications of gastric bypass include enteric leak or sepsis, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, compartment syndrome, or early obstruction.[30] Best practice guidelines have been published recommending specific surgical techniques, equipment, and hospital resources for facilities performing weight loss surgery in order to minimise such complications.[31][32][33]

Enteric leak or sepsis

The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) has published guidelines on the prevention and detection of enteric leaks after gastric bypass.[34]

Leaks may occur at the proximal anastomosis (gastric-jejunostomy), distal anastomosis (jejunojejunostomy), pouch staple line, gastric remnant staple line, or other areas along the stomach, plus small and large bowel. Rates of gastrointestinal leak range from 2% to 3% and are not affected by choice of laparoscopic versus open approach.[35][36]

Symptoms include abdominal pain, back or shoulder pain, and anxiety or feeling of impending doom.

Signs include tachycardia >110-120 beats per minute, fever (>38.5°C [101.3°F]), respiratory distress (shortness of breath or tachypnoea >20 breaths per minute), or a post-operative recovery that differs from expected course. Traditional signs of abdominal sepsis such as tenderness, rebound pain, or guarding may be unreliable or absent in the abdomen with central adiposity.

Imaging findings are commonly falsely negative, although a positive upper gastrointestinal series or computed tomography (CT) scan may be helpful in diagnosing enteric leak. A negative study does not eliminate enteric leak from the differential diagnosis.

Treatment includes broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and resuscitation, which should be started early. If the diagnosis is in doubt, surgical exploration as soon as possible is advisable. Re-exploration may be performed using laparoscopic or open techniques. See Sepsis in Adults.

Operative intervention generally includes irrigation of peritoneal cavity, sewing over of leak site with placement of omental patch, placement of drain(s) near leak site, and insertion of feeding access into gastric remnant or jejunum.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)

DVT/PE occurs mainly following discharge after bariatric surgery.[37]

DVT with subsequent PE may be the most common cause of death post-bariatric surgery.[38] Approximately 1% to 2% of patients will develop PE, with a mortality rate of 0.2% to 0.6%.[39][40] Predisposing factors for DVT/PE include obesity, general anaesthesia, and impaired mobility, which are present in all patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Additional risk factors include age less than 50 years, previous DVT/PE, smoking history, revisional operation, open surgery, anastomotic leak, congestive heart failure, paraplegia, and dyspnoea at rest.[37][41]

Several health organisations have published recommendations for DVT/PE prophylaxis in bariatric surgery. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has published guidelines for reducing the risk of DVT/PE in hospitalised patients, which includes recommendations for patients undergoing bariatric surgery.[42] The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has published a position statement on prophylactic measures to reduce the risk of DVT/PE in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.[43]

Preventative measures following surgery include early mobilisation, sequential compression devices or anti-embolism stockings, and pharmacological thromboprophylaxis.[42][43] Due to the complications associated with the use of inferior vena cava filters, they are generally not recommended for thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.[10]

Diagnostically characteristic findings of DVT/PE (shortness of breath, chest pain, tachycardia) are not specific and may also suggest the diagnosis of enteric leak. Lower extremity DVT is usually diagnosed by Doppler ultrasound. CT angiography is effective in making the diagnosis of PE. The diagnosis of DVT with CT angiography is less well described in this situation. See Deep vein thrombosis and Pulmonary embolism.

Gastrointestinal (GI) haemorrhage

GI haemorrhage may present as an upper GI bleed with haematemesis, or as a lower GI bleed with bright red blood per rectum. The reported incidence of GI bleeding ranges from 1% to 4%.[35] Upper GI bleeding typically originates from the proximal anastomosis or the gastric pouch staple line. Lower GI bleeding typically originates from the distal anastomosis or the bypassed stomach (gastric remnant). As with any abdominal operation, intraperitoneal bleeding may occur from a staple line or from surgical injury to the spleen, mesentery, or omentum.

Management of postoperative GI bleeding includes:

Review of medications and discontinuation of any that enhance bleeding, such as heparin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Observation, if the patient is in a stable condition and bleeding is not excessive.[44]

Endoscopy and/or immediate re-exploration under general anaesthesia should be considered if the patient is not in a stable condition or is bleeding excessively and persistently.

Compartment syndrome, characterised by:

Intra-abdominal oedema and sustained elevation in intra-abdominal compartment pressure above 20 mmHg, causing end-organ failure as a result of venous outflow obstruction.[45] This may result in abdominal sepsis, bleeding, or bowel obstruction. Oliguria and renal failure may be the first manifestations.

Respiratory failure can occur because of interference with diaphragmatic excursion.

Diagnosis of compartment syndrome is achieved by measuring bladder pressure via pressure transducer, with a Foley catheter attached to 3-way stopcock. After the bladder is emptied, 25 cc of saline is introduced and the catheter is clamped. The pressure inside the catheter lumen is transduced and measured. Pressure greater than 25 mmHg will require surgical decompression by opening the abdomen.

Abdominal compartment syndrome is treated by optimisation of fluid balance, evacuation of intraluminal contents, and analgesia. Surgical decompression may be necessary if abdominal compartment syndrome is refractory to other treatment options.[45] See Abdominal compartment syndrome.

Early obstruction

Early obstruction is uncommon but needs to be recognised and treated promptly, because of the risk of disrupting a fresh anastomosis or staple line.[46]

Obstruction at the proximal anastomosis may occur because of oedema at the gastric-jejunostomy. This typically resolves with time and may be treated expectantly.

Early obstruction most commonly occurs at the distal anastomosis because of kinking of the bowel approximately 2 weeks after surgery.[46] Occlusion of the biliopancreatic limb may not be visible on plain radiographs; therefore, abdominal CT is required for diagnosis. In patients who have a stable condition, performing a CT-guided percutaneous decompression of the gastric remnant may temporise the situation and permit non-operative treatment. If this is not possible, revision of the distal anastomosis or bypass of the obstruction with a Braun 'omega'-type loop may be necessary.

Wound infection

Wound infection is reported in up to 20% of open gastric bypasses.[47]

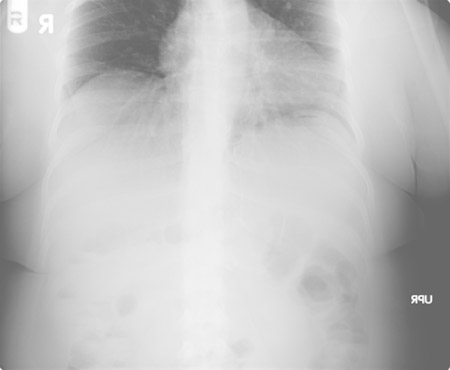

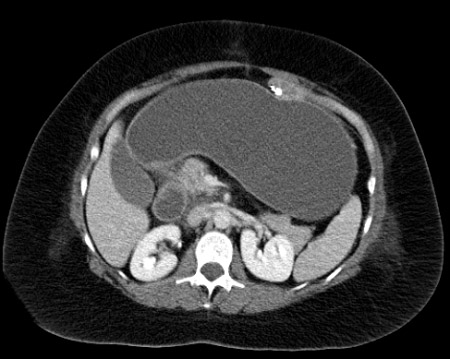

Wound infection rate was found to be lower in laparoscopic RGBs (1%) than in open RGBs (10%) in one study.[29][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain radiographic view of an obstruction at the distal anastomosis. No air bubble is visible in the bypassed stomach (gastric remnant)From collection of Daniel M. Herron, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of the abdomen in the same patient reveals a tremendously dilated gastric remnant. With CT guidance, a dilated remnant is easily accessed percutaneouslyFrom collection of Daniel M. Herron, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of the abdomen in the same patient reveals a tremendously dilated gastric remnant. With CT guidance, a dilated remnant is easily accessed percutaneouslyFrom collection of Daniel M. Herron, MD [Citation ends].

Late complications are considered to be those occurring more than 30 days after surgery. They include:

Vomiting due to stricture

Stricture of the proximal anastomosis is the most common complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Reported incidence ranges from 0.6% to 27%.[48]

Symptoms generally appear 3 to 6 weeks after surgery and include increasing intolerance of solids and ultimately liquids. There may be associated dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting.[49]

Diagnosis is based on history and confirmed with endoscopy. Simultaneous endoscopic balloon dilation to 10 mm to 15 mm results in immediate symptomatic relief. Patients may be immediately re-started on a diet of pureed food. Many strictures require 2 or more dilations.[50]

Upper gastrointestinal contrast swallow is not generally necessary and may delay therapeutic endoscopic treatment or result in aspiration of contrast.

Use of linear stapler rather than circular stapler to form the proximal anastomosis may lead to decreased stricture rates, although stricture rates may be equivalent regardless of technique.[51]

Internal abdominal hernia

Abdominal pain in patients who have had a bypass should always suggest the possibility of internal hernia, particularly if it occurs 3 months or more after surgery. Incidence is approximately 3%.[52]

Pain is typically epigastric and may radiate to the back. Symptoms may be acute or chronic, and may mimic biliary colic.

Patients may complain of multiple similar episodes of pain. They may also have undergone ultrasound, upper gastrointestinal series, or computed tomography, which can be negative even in the presence of an internal hernia.[53]

The three spaces where hernia may occur in patients who have had a gastric bypass are:

Peterson hernia space, located behind the Roux (alimentary) limb

Distal mesentery space, located between the 2 leaves of mesentery at the distal anastomosis

Mesocolic space, located in gastric bypasses with a retrocolic Roux limb (placed through an iatrogenic opening in the mesocolon). The bowel may herniate through this space.

Pain occurs because the bowel becomes entrapped in one of these spaces and blood supply is compromised. If ischaemia is persistent, necrosis of the intestine will occur. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ischaemic small bowel entrapped within a distal mesenteric herniaFrom collection of Daniel M. Herron, MD [Citation ends].

Definitive diagnosis can only be made through laparoscopic or open surgical exploration. The bowel must be reduced from the herniated position, and necrotic intestine must be resected. All hernia spaces should be closed with continuous permanent suture material.

Marginal ulcer

Marginal ulcers are a common source of pain or perforation after gastric bypass. They are not associated with sleeve gastrectomy or gastric banding.

Aetiology is unclear. They are likely to be related to acid exposure or the presence of foreign bodies (e.g., staples or permanent suture material) at the proximal anastomosis.[54]

Marginal ulcer formation is strongly associated with fistulae from the low-pH gastric remnant to the gastric pouch.[55]

Risk factors include smoking, diabetes, and peptic ulcer history.[56][57]

Ulcers generally form just distal to the gastric-jejunostomy.

Symptoms range from minor intermittent epigastric pain to severe generalised abdominal pain if perforation occurs.

Ulcers are easily diagnosed with upper endoscopy.

Simple ulcers may be treated with acid reduction therapy. Suture material at the ulcer site should be removed endoscopically if possible. The presence of a gastrogastric fistula between the pouch and gastric remnant requires surgical revision.

Incisional hernia

Cholelithiasis

Cholelithiasis may occur in 32% of patients after surgically induced weight loss and may result in biliary colic or acute cholecystitis.[60]

Some bariatric surgeons routinely perform cholecystectomy at the time of gastric bypass. Others perform it only in the presence of documented cholelithiasis. However, many surgeons leave asymptomatic gallbladders in place, regardless of whether or not gallstones are present.

Prophylactic ursodiol (ursodeoxycholic acid) after surgery may reduce the risk of postoperative gallstone formation.[61]

Indications for cholecystectomy include symptomatic cholelithiasis, acute or chronic cholecystitis, or history of gallstone pancreatitis.

Because gastric bypass anatomy precludes endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, a cholangiogram can be performed at the time of cholecystectomy to identify the presence of common bile duct stones.

In patients with abdominal pain after gastric bypass, cholelithiasis does not eliminate the possibility of internal hernia and it may be difficult to determine whether their pain is a manifestation of symptomatic cholelithiasis or undiagnosed internal hernia. If the patient is taken to the operating theatre for cholecystectomy, the gastric bypass anatomy should be carefully evaluated and any internal hernias repaired at that time.

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is now the most common bariatric procedure due to its technical simplicity and minimal long-term metabolic effects.[62][63][64][65] One randomised prospective trial comparing SG with gastric bypass revealed very similar weight loss, complications, and quality of life 1 year after surgery in both groups.[66] Compared with the gastric band, SG has several significant advantages: it results in better weight loss, there is no foreign body implanted within the abdomen, and there is no need for adjustment. It may be considered the best surgical option for a patient at high risk for poor adherence to diet or limited follow-up.

In SG, the greater curvature (left side) of the stomach is resected, leaving a narrow, banana-shaped stomach in place. The small intestine is not involved in this operation, so there is no alteration to the alimentary path.

Some studies suggest that sleeves fashioned over a larger sizing bougie (40 French/13 mm or greater) may have a lower leak rate.[67]

After SG, the remaining portion of the stomach is accessible endoscopically. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be performed if needed. This differs from the gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion, where a significant portion of the stomach or small intestine is unreachable endoscopically, thus precluding routine ERCP in most circumstances.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sleeve gastrectomyCopyright ©2008 Daniel M. Herron, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

There are no surgical anastomoses in the sleeve gastrectomy (SG). However, the long staple line may leak (0.7% risk) or bleed (0.7%).[68][69] Leakage may be more difficult to treat than in gastric bypass but may respond to endoscopic stenting.[70][71]

Patients may develop nausea and vomiting in the early post-operative period, generally 1 to 2 weeks after surgery. This may be caused by post-operative oedema or kinking of the stomach. Symptoms usually improve if upper endoscopy is performed, as it serves to minimally dilate and straighten the pouch. If a frank stricture is seen, it will probably respond to endoscopic balloon dilation. Persistent nausea without mechanical obstruction may respond to medical therapy.

Dilation of the sleeve may occur over time, leading to decreased restriction, increased oral intake, and weight regain. In these cases, surgical revision may be indicated.[72]

Overall readmission rate for patients who have had SG is about 5%.[73] Some studies suggest that sleeves fashioned over a larger sizing bougie (40 French/13 mm or greater) may have a lower leak rate, though there is variation in both sleeve caliber and weight loss.[67][74]

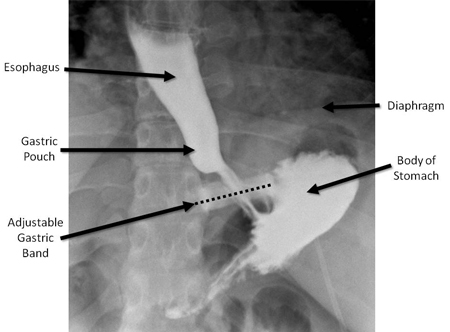

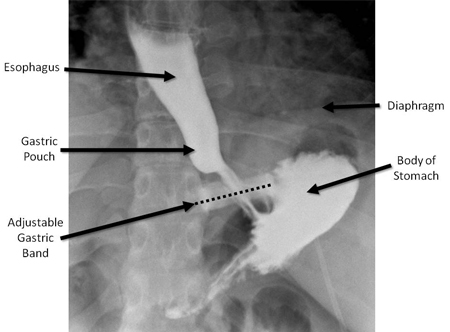

The gastric band is one of the least frequently performed bariatric operations. Device-related reoperation is common and costly.[75] Long-term outcomes suggest weight loss results are lower than those seen with bypass or sleeve gastrectomy.[76] Several adjustable gastric band (AGB) devices are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. They are generally placed around the body of the stomach just distal to the gastro-oesophageal junction and act by restricting gastric volume.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric bandCopyright ©2008 Daniel M. Herron, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. The vast majority of AGB operations are performed via laparoscopic approach. In general, open surgery is used only when technical considerations preclude a laparoscopic approach. Typically, 5 to 6 incisions, each 5 mm to 15 mm, are used for laparoscopic access. One incision is enlarged to allow attachment of the access port to the abdominal wall. The AGB is placed around the superior portion of the stomach, just beneath the gastro-oesophageal junction. The inner portion of the band includes a toroidal balloon that can be inflated with saline, injected through the subcutaneous access port. Saline capacity may range from 4 mL to 15 mL, depending on the specific device. Injecting saline into the port tightens the band, and removing saline loosens the band. In general, bariatric surgeons tighten bands just enough to result in restriction of intake, but not so tight as to cause vomiting, discomfort, or oesophageal widening (pseudoachalasia). Saline capacity may range from 4 mL to 15 mL. The access port is usually clearly visible on plain abdominal radiograph, and can typically be palpated on examination of the abdomen. On radiographs, the band generally appears to be rotated about 20-40 degrees from horizontal, with the left side higher than the right. Bands that are angulated differently may have slipped from their normal position.

The vast majority of AGB operations are performed via laparoscopic approach. In general, open surgery is used only when technical considerations preclude a laparoscopic approach. Typically, 5 to 6 incisions, each 5 mm to 15 mm, are used for laparoscopic access. One incision is enlarged to allow attachment of the access port to the abdominal wall. The AGB is placed around the superior portion of the stomach, just beneath the gastro-oesophageal junction. The inner portion of the band includes a toroidal balloon that can be inflated with saline, injected through the subcutaneous access port. Saline capacity may range from 4 mL to 15 mL, depending on the specific device. Injecting saline into the port tightens the band, and removing saline loosens the band. In general, bariatric surgeons tighten bands just enough to result in restriction of intake, but not so tight as to cause vomiting, discomfort, or oesophageal widening (pseudoachalasia). Saline capacity may range from 4 mL to 15 mL. The access port is usually clearly visible on plain abdominal radiograph, and can typically be palpated on examination of the abdomen. On radiographs, the band generally appears to be rotated about 20-40 degrees from horizontal, with the left side higher than the right. Bands that are angulated differently may have slipped from their normal position.

For band adjustments, the skin is prepared with an antibacterial agent, typically alcohol or povidone-iodine. The port can then be accessed with a special, non-coring, Huber-type needle. Use of a standard hollow-bore needle to access the port may result in permanent damage to the access port. If the port cannot be palpated, fluoroscopic guidance may be required.

After band placement, the stomach remains accessible to upper endoscopy, although it may be necessary to remove some or all of the fluid from the band beforehand.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Upper GI series in patient with adjustable gastric band in normal position. The dashed line is superimposed over the band to emphasise the normal angulation of the band, with the left side angled upwards approximately 20-40 degrees from the horizontal. Note the very small pouch between the band and the diaphragmFrom collection of Daniel M. Herron, MD [Citation ends].

Early complications are those that occur less than 30 days after surgery. Surgical injury to the stomach or intra-abdominal oesophagus may result in immediate or early gastrointestinal (GI) leak and sepsis. Early GI leak requires immediate re-operation with removal of the band, closure and patch of the injury, and drainage.

Surgical oedema at the site of the band may result in early surgical obstruction in 1.5% of patients.[77] Obstruction due to oedema may be treated with band removal.

Venous thromboembolism is the most common cause of death in patients with a gastric band.[78] Mechanical and/or pharmacological deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis should be used as necessary.[37]

Breakage of the access port or connecting tubing may occur in up to 8% of patients with a gastric band.[79]

Band slippage, which may lead to gastric prolapse, may occur in 5% or more of patients.[77] Abdominal plain films show a normal band angle of approximately 20 to 40 degrees from horizontal, with the left side higher than the right side. Bands that are angulated differently may have slipped from their normal position. A vertically-oriented band suggests a band slippage with the posterior stomach prolapsed through the band, whereas a horizontally-oriented band suggests an anterior slippage. Slippage usually results in partial or complete obstruction of the stomach and associated abdominal pain. Deflation of the band may relieve symptoms. Persistent symptoms after deflation may indicate vascular compromise of the stomach, requiring urgent surgical revision or removal of the band.

Patients with obstruction or pain should have all the fluid in the band removed. The access port is localised by palpation or fluoroscopy and accessed with a Huber-type non-coring needle.

Gastric bands occasionally erode through the gastric wall and lead to infection.[80][81] This should be suspected in a patient with cellulitis at the site of the access port, because the infection may track along the tubing to the level of fascia or skin. Erosion is diagnosed with endoscopy and treated with antibiotics and band removal. Patients with a gastric band may develop oesophageal dilation, or oesophageal widening (pseudoachalasia), in the long term. This is initially treated with band deflation, followed by band removal if necessary.[82] The access port may rotate, precluding percutaneous access. Such a complication would require surgical revision. The overall incidence of port-related complications was reported to be 11.2% in a European study of 1791 patients over 12 years.[83][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Upper GI series in patient with adjustable gastric band in normal position. The dashed line is superimposed over the band to emphasise the normal angulation of the band, with the left side angled upwards approximately 20-40 degrees from the horizontal. Note the very small pouch between the band and the diaphragmFrom collection of Daniel M. Herron, MD [Citation ends].

The BPD, sometimes referred to as the Scopinaro procedure, is only moderately restrictive but causes substantial malabsorption. Like the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the BPD involves reduction of the stomach volume and surgical division of the small bowel with Y-shaped reconstruction. However, the stomach pouch remains much larger than in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the amount of bowel bypassed is much greater, and the common channel is much shorter (50 cm to 100 cm). This results in less restriction but far greater malabsorption than with the gastric bypass.

In BPD, the stomach volume is reduced by resecting the antrum of the stomach (antrectomy).

The biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) is a modification of the BPD. The antrum is left intact while the greater curvature (left side) of the stomach is resected. This results in a banana-shaped 'sleeve gastrectomy' 100 cc to 200 cc in volume. The distal end of the pouch is formed by dividing the first portion of the duodenum several centimetres distal to the pylorus. This modification is intended to reduce dumping syndrome and ulceration of the anastomosis.

The biliopancreatic limb is inaccessible to upper endoscopy or colonoscopy. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography cannot be performed.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS)Copyright ©2008 Daniel M. Herron, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Surgical complications of BPD or BPD-DS are similar to those of gastric bypass. Surgical revision for malnutrition is required in less than 1% of patients who have had BPD-DS. Operative mortality is approximately 1%.[73]

A newer variant of the BPD or BPD-DS is the Single Anastomosis Duodeno-ileostomy with Sleeve (SADI) which appears to have similar outcomes to BPD or BPD-DS.[84][85]

It is important to preoperatively screen patients’ micronutrient levels, as vitamin or mineral deficiencies are common prior to bariatric surgery.[86] Patients should be educated about expected deficiencies both before and after bariatric surgery. Follow-up monitoring is important, as data suggest the prevalence of nutritional deficiency after surgery is increasing.[86]

There is no standard regimen for nutritional supplementation after bariatric surgery but various clinical guidelines provide recommendations for peri- and postoperative nutrition and metabolic support.[86][87][88][89][90]

Following any bariatric surgery, long-term protein intake should be encouraged.[90] The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery guidelines recommend that patients take vitamin B₁, B₁₂, D, A, E and K, folic acid, iron, calcium, zinc and copper supplements.[86] A typical post-gastric bypass regimen includes:

Multivitamin supplementation (including vitamin B₁, vitamin B₁₂ [cyanocobalamin], and vitamin D) with iron, twice daily. Chewable supplements may be better tolerated than swallowed pills.

Calcium supplementation: calcium citrate is generally preferred over calcium carbonate due to its better absorption in patients with a gastric bypass.[91] Supplements with additional vitamin D may be beneficial due to the high incidence of vitamin D deficiency in the bariatric surgery population.[92]

Iron supplementation: iron polysaccharide complex may be better tolerated and absorbed than ferrous sulfate.

Zinc, magnesium, and phosphorus supplementation: can be taken as part of oral multivitamin and mineral supplementation. Zinc supplements can induce copper deficiency and vice versa; therefore, copper supplementation will likely need to be given concurrently with zinc.

Bariatric operations that bypass the duodenum or jejunum (i.e., gastric bypass and biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch) reduce absorption of iron, calcium, and other divalent cations, and so require more supplementation than non-bypass operations. Since no intestine is bypassed in the sleeve gastrectomy and adjustable gastric band procedures, these patients may be maintained with minimal supplementation, such as a daily multivitamin with or without additional calcium.

It should be emphasised that any supplementation regimen such as the one outlined above is merely a starting point, and that all patients who have had bariatric surgery need to be followed with regular bloodwork to assess their vitamin status. Supplementation regimens may then be customised for each patient as needed.

Procedure- and complication-specific deficiency

Severe vomiting after bariatric surgery may result in vitamin B₁ deficiency and Wernicke's encephalopathy. Neurological symptoms include ataxia, confusion, and blurred vision. Patients should not be treated with dextrose-containing intravenous fluids as this may result in permanent neurological injury. Instead, normal saline or Ringer's lactate solution should be used with added thiamine and multivitamin.[93]

Protein deficiency may be seen after malabsorptive procedures that involve bypassing large portions of small intestine. Physical examination may demonstrate oedema, alopecia, and asthenia. Laboratory studies may show hypoalbuminaemia and anaemia.[94] Incidence approaches 13% after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RGB) and 18% following biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS).[95] Milder cases may respond to increased oral protein intake. Severe cases may require total parenteral nutrition or surgical revision.

Iron deficiency is most likely in bariatric procedures such as gastric bypass and BPD-DS, in which the duodenum is bypassed. Rates may be as high as 50%.[95] Mild cases will respond to oral supplementation, whereas more severe cases require intravenous replacement.

Vitamin B₁₂ and folate may become deficient when the proximal small bowel is bypassed. Supplementation is generally recommended after RGB and BPD-DS. Vitamin D deficiency is very common and is associated with calcium deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism.[96][97] This can be reduced with calcium citrate and vitamin D supplementation. Moderate sunlight exposure is also helpful.

Zinc deficiency is common after BPD-DS, which may be a result of fat malabsorption following this surgical procedure.[86] Zinc deficiency may also occur following gastric bypass, but is less common compared with BPD-DS.

Certain medications, specifically those that are fat-soluble or that undergo enterohepatic circulation, may be poorly absorbed or metabolised after bariatric surgery.[98][99]

Bariatric surgery is associated with reductions in bone density and a negative impact on bone metabolism.[100][101][102][103] The risk is greater following malabsorptive procedures than restrictive procedures.[104] Reduction in fat mass, malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D, decreased mechanical loading following weight loss, reduced nutritional intake, insufficient exercise, and changes in hormonal and metabolic profiles have all been thought to impact on bone metabolism after bariatric surgery.[100][102][105] One meta-analysis of 10 studies found that, in patients with class III obesity, bone mineral density was significantly decreased, bone turnover elevated, and bone remodelling accelerated following bariatric surgery.[103] Studies have found increased bone turnover to be correlated with change in BMI, and decrease in bone mineral density to be independent of weight after bariatric surgery.[106][107] In another study, patients with diabetes who underwent bariatric surgery had chronically elevated bone turnover (5 years after the intervention) compared with those who received intense medical therapy.[108]

All types of bariatric surgery result in lower femoral neck bone density compared with non-surgical control groups.[109]Surgery does not reduce bone density at the lumbar spine.[109] Roux-en-Y and sleeve gastrectomy are both associated with declines in hip and lumbar spine bone mineral density one year after surgery.[101] Roux-en-Y bypass leads to a greater loss of femoral neck and total hip areal bone mineral density than sleeve gastrectomy; however, sleeve gastrectomy is associated with increased vertebral and femoral marrow adipose tissue (which may impair skeletal health), lower weight loss and visceral fat loss.[101]

The effects on bone and mineral metabolism vary depending on the surgical procedure (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding or sleeve gastrectomy) and persist beyond the first year after surgery.[100] Close monitoring and supplementation of calcium and vitamin D is advisable to prevent secondary hyperparathyroidism and bone loss following bariatric surgery.[103]

Patients who have had bariatric surgery are generally recommended to postpone pregnancy until a stable weight is achieved (typically 1 year after sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures and 2 years after adjustable gastric band).[110][111] Both negative and positive effects of bariatric surgery on fertility and pregnancy outcomes have been reported.[112][113][114] One cohort study conducted in Denmark found that babies born to women who had undergone bariatric surgery had lower birth-weight, lower gestational age, and a lower risk of being large for gestational age than those born to a matched group of women without bariatric surgery.[115]

In order to help patients sustain weight loss after bariatric surgery, regular self-monitoring and frequent postoperative follow-up visits are required.[116] Inadequate weight loss or weight regain may occur in 10% or more of patients who have had bariatric surgery.[39][117][118][119] This may result from non-intact surgical anatomy, or it may be due to more complex psychological and behavioural factors. Studies have identified longer time-lapse since surgery, younger age, inadequate control over food urges, addictive behaviours, and decreased post-operative well-being as possible predictive factors for post-operative weight regain.[116][120]

Initial evaluation

Evaluation of patients with inadequate weight loss or weight regain requires a systematic approach.

Initial evaluation includes a detailed nutritional and activity history. This should include a thorough review of postoperative behavioural adherence with diet, nutritional supplementation, exercise, and follow-up programmes.

Surgical anatomy should be assessed with upper gastrointestinal series and upper endoscopy to ensure the procedure remains intact.

Weight-loss pharmacotherapy may be considered if the patient has intact surgical anatomy, but has inadequate weight loss or weight gain despite post-operative adherence with diet, nutritional supplementation, and exercise.[120][121][122]

Nonintact surgical anatomy

Upper GI series and endoscopy may reveal that the original surgical anatomy is no longer intact. Examples include:

Excessively large gastric pouch (estimated volume >30 mL) after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RGB). This usually leads to weight regain, as a result of the decrease in gastric volume restriction, and may result in vomiting due to poor pouch emptying.

Formation of gastrogastric fistula after RGB. This often leads to marginal ulcer formation as well as weight regain.

Prolapse of stomach through a gastric band, resulting in an excessively large pouch.

Weight loss failure attributable to nonintact surgical anatomy generally requires reoperation to re-establish the desired surgical anatomy. Bariatric revisional surgery carries a substantially higher risk of morbidity and mortality than primary surgery.

Monitoring

Regular self-monitoring and frequent post-operative follow-up visits over the long term may help patients to sustain weight loss following bariatric surgery.[116]

Approach to managing abdominal pain in patients who have had bariatric surgery:

After initial evaluation and resuscitation, the patient’s bariatric surgeon or the local bariatric surgeon on call should be contacted immediately.

The date of surgery should be ascertained, as the causes of pain vary based on the post-operative period.

A complete blood count with differential will be helpful to determine if there is infection, inflammation, or haemorrhage. Serum electrolytes are useful in a patient who has had poor oral intake. Amylase/lipase and liver function tests will help to diagnose pancreatitis, cholecystitis, or hepatobiliary problems. Coagulation studies may be useful in a patient with a malabsorptive operation, as vitamin K deficiency may elevate the prothrombin time.

New-onset abdominal pain in the first 2 weeks after surgery raises the concern of enteric leak, typically from a staple line or anastomosis. Computed tomography (CT) scan with oral contrast will be useful in identifying leakage, intra-abdominal fluid, or abscess. Upper gastrointestinal series with water-soluble contrast is very helpful in identifying a leak from the stomach or proximal jejunum, but may be less useful for distal leaks. Generally, enteric leak requires immediate return to the operating theatre for washout, repair of the leak, drain placement, and placement of enteral feeding access. Well-contained leaks in patients who have a stable condition may occasionally be managed non-operatively.

Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain occurring at 3 months or more following bariatric surgery is suggestive of cholecystitis or marginal ulcer. Abdominal ultrasound is the single best study for evaluating the gallbladder. Upper endoscopy will reveal gastritis or marginal ulcer if present.

Patients with a gastric band who experience acute abdominal pain may be suffering from an acute band slip or gastric prolapse, which can be diagnosed with upper GI series radiographs.

If the patient is 3 months or more post surgery, abdominal pain may also be due to an internal hernia. While this may be seen on CT scan, it is very possible that all imaging will be negative. Immediate surgical consultation should be obtained to determine whether surgical exploration is warranted.

Rapid onset of pain in the absence of any prior symptoms is strongly suggestive of perforated marginal or gastric remnant ulcer.

Chronic intermittent pain in the epigastrium radiating to the back is strongly suggestive of internal hernia and should be diagnosed with surgical exploration if no other pain source is identified.

Approach to managing nausea and vomiting in patients who have had bariatric surgery:

Nausea and vomiting in the first week after gastric bypass may be suggestive of anastomotic oedema, which typically resolves spontaneously. If the patient is more than 2 weeks post surgery, anastomotic stricture is the most likely diagnosis. This can be diagnosed and treated with upper endoscopy and balloon dilation.

Patients with a gastric band who experience nausea and vomiting should have the band loosened immediately. If this fails to relieve the symptoms, upper gastrointestinal series should be obtained urgently to assess for continued obstruction, suggestive of band slip or gastric prolapse.

Nausea and vomiting is common in post-operative sleeve gastrectomy patients. Upper endoscopy will demonstrate whether a mechanical obstruction is present, and may also be therapeutic by gently dilating an oedematous or kinked sleeve.

If any postoperative bariatric surgery patient has prolonged nausea and/or vomiting, opportunities should be made for intravenous hydration and thiamine supplementation.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer