Approach

A thorough history, physical examination, review of the full blood count (FBC), and peripheral blood smear are necessary to narrow down the differential diagnosis of neutrophilia. The clinical history should include an investigation of the chronicity of the presentation. Review of the peripheral blood smear should evaluate for a concurrent left shift (an increase in immature granulocytes in the peripheral circulation).

Clinical history

Determining the aetiology to an elevated neutrophil count requires thorough assessment of the clinical history with a focus on the chronicity of the disease. Neutrophilia may result from disease processes that are present for a matter of seconds or minutes to weeks or months.

Transient causes of neutrophilia include muscular convulsions (e.g., tonic-clonic seizure), emesis, ovulation, obstetric conditions (pre-eclampsia, and spontaneous or caesarean delivery), carbon monoxide poisoning, infection, a thyroid storm, acute coronary syndrome and myocardial infarction, and trauma (thermal burn, electric shock, surgery, and snake bites).

Chronic conditions that result in neutrophilia include pregnancy and lactation, acidosis, Down's syndrome, conditions associated with anxiety and stress, and hypercortisolism.

A thorough review of the past medical history may identify conditions that are chronic, episodic, or recurrent that may either directly cause, or contribute to causes of, neutrophilia. The following should be screened for:

Chronic inflammatory conditions, including inflammatory autoimmune diseases

Chronic or recurrent infections

Conditions associated with anxiety and stress

Trisomy 21 (Down's syndrome)

Antecedent haematological disease (myeloproliferative neoplasm, myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm)

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

Sickle cell disease

Surgical history (including splenectomy)

Recent immunisation.

A detailed drug history, including recently discontinued drugs, non-prescription drugs, and supplements, should be taken. Specific drugs known to be associated with neutrophilia include:

Antibiotics (a history of recent antibiotic use and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea should be elicited and C difficile colitis considered even without symptomatic diarrhoea if there is a history of prior antibiotic use)

Corticosteroids

Catecholamines (epinephrine [adrenaline])

Lithium

Granulocyte (G-CSF) and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factors (GM-CSF)

All-trans retinoic acid or arsenic trioxide for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukaemia (AML-M3 by French-American-British classification).

A family history of neutrophilia suggests hereditary neutrophilia. Other conditions that should be screened for include familial cold urticaria and leukocytosis, Down's syndrome, and leukocyte adhesion factor deficiency.

A comprehensive social history is necessary to identify possible contributing factors and should include questioning on the smoking status, and level of emotional and physical (including vigorous exercise) stress of the patient.

Physical examination

An initial focused physical examination for signs of infection or inflammation should be performed, with particular attention to the following:

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome: defined as the presence of at least 2 of the following criteria: 1) fever >38°C, 2) heart rate >90 bpm, 3) respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute or PaCO₂ <32 mmHg, 4) total WBC count >12×10⁹/L or <4×10⁹/L, or >10% bands (immature neutrophils have a band-shaped nucleus).[2]

Fever, tachypnoea, hypotension, tachycardia, and septic shock

Hypothermia

Lymphadenopathy suggesting infection or malignancy

Soft tissue erythema, heat, and oedema suggesting localised soft tissue infection, cellulitis, or abscess

Signs of pulmonary consolidation or pleural effusions on respiratory examination

Abdominal tenderness and signs of peritonitis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, or other aetiologies of an acute abdomen

Examination of the stool: foul-smelling and loose stool suggesting C difficile colitis.

This should be followed by a secondary examination to evaluate for an undiagnosed malignancy. Splenomegaly suggests myeloproliferative neoplasm or chronic myeloid leukaemia.

Initial tests

All patients should have a FBC performed and a peripheral blood smear reviewed. Other initial laboratory tests should be guided by the results of the clinical history and physical examination.

The degree of leukocytosis should be immediately evaluated, as total leukocyte counts >250×10⁹/L may require immediate leukopheresis to prevent complications to end organs, including respiratory failure, stroke, or myocardial infarction due to occlusion of the pulmonary, intracranial, or coronary circulation, respectively.

Review of the FBC and peripheral blood film expedites evaluation of urgent underlying causes of neutrophilia.

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML): elevated total leukocyte count with evidence of immature myeloid cells in the circulation with associated anaemia and thrombocytopenia.

Myeloproliferative neoplasm or myeloproliferative/myelodysplastic overlap syndromes: evidence of dyspoiesis, and/or elevated myeloid subsets. Diagnosis supported by evidence of immature cells in the peripheral circulation. Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is associated with an elevated total leukocyte count with left shift and evidence of full myeloid maturation. Diagnosis supported by basophilia, eosinophilia, and thrombocythaemia.

Anaemia: decreased haemoglobin with a variable reticulocyte count (may be elevated or reduced).

Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemias: microangiopathic changes to the red blood cells (fragmented red blood cells, reticulocytosis) and enlarged platelets. Neutrophilia or leukocytosis with a total leukocyte count >20×10⁹/L.

Sepsis with or without disseminated intravascular coagulation: concurrent thrombocytopenia and neutrophilia with morphological changes evident on the peripheral blood smear, including toxic granulations, Dohle bodies, and cytoplasmic vacuoles.

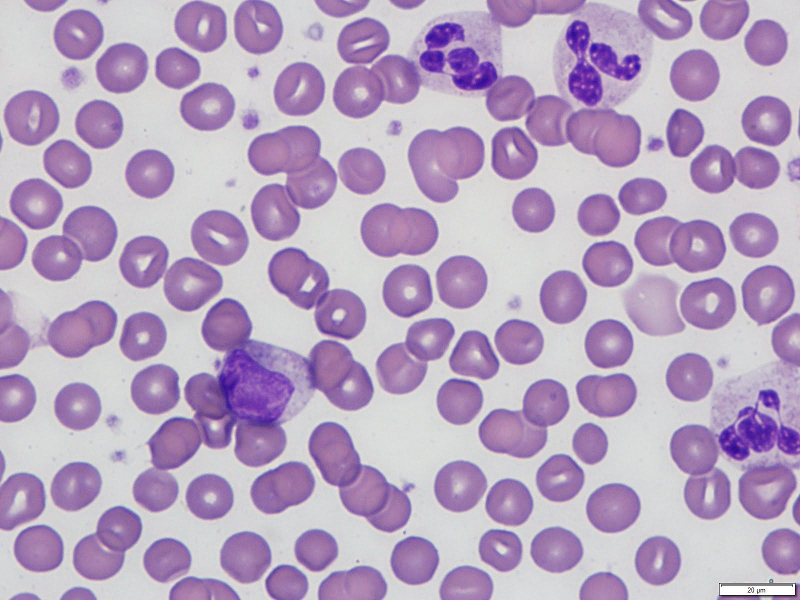

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Neutrophilia with left shiftFrom the collection of D. Chabot-Richards, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

The peripheral blood smear should be evaluated for a left shift (an increase in immature granulocytes in the peripheral circulation). Immature myeloid cells seen in a left shift include increased blasts, promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes.

Monocytosis (an increase in the blood absolute monocyte count to >0.8×10⁹/L) may be evident on the peripheral blood smear concurrently with a neutrophilia in a variety of conditions, including autoimmune disorders, depression, infections (tuberculosis, malaria, typhoid fever, syphilis, trypanosomiasis, varicella zoster virus infection, brucellosis), inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, an asplenic or hyposplenic state, pregnancy, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and myelodysplastic syndrome (chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia), as well as with corticosteroid or colony-stimulating factor treatment.

Histology of the peripheral blood smear should be evaluated to exclude evidence of immature myeloid cells suggesting an acute leukaemic process. Immature cells seen in a left shift may be as immature as metamyelocytes, but evidence of myelocytes, promyelocytes, or blasts on the peripheral blood smear requires immediate investigation for possible acute leukaemia.

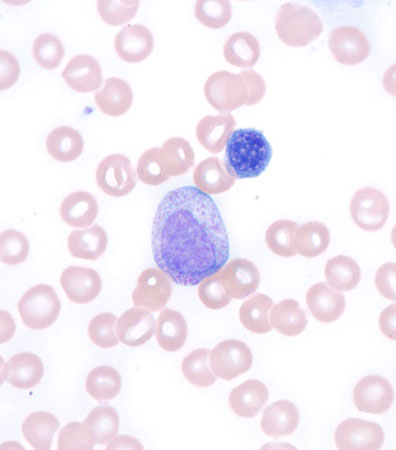

Histological findings that support an infectious or inflammatory condition include toxic granulations, Dohle bodies, and cytoplasmic vacuoles. Evidence of these changes to the neutrophil morphology are highly sensitive (80%), although not specific (58%), for an existing inflammatory or infectious condition.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Leukoerythroblastic peripheral blood smearFrom the collection of T. George, MD [Citation ends].

Targeted investigations

After evaluating the FBC and reviewing the peripheral blood smear, specific additional laboratory tests based on the pretest probability of the differential diagnosis should be performed.

If an infectious process is suspected, the source of the infection should be identified by blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, sputum, or wound cultures (both aerobic and anaerobic).

If an inflammatory or infectious cause is suspected, elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP), although a low-sensitivity test, should be determined. A CRP >95.2 nanomol/L (1 mg/dL or 10 mg/L) has a sensitivity of 79% for inflammation or infection. An elevated total leukocyte count, increased ratio of neutrophils within the total leukocyte count, or elevated CRP have a 100% sensitivity for an inflammatory or infectious condition. However, the positive predictive value of the combination is poor at 37%.[25] Erythrocyte sedimentation rate can also be measured to support an inflammatory or infectious cause for the neutrophilia.

Imaging, including chest x-ray, abdominal ultrasound, or computed tomography (localised to the possible source based on the physical examination) may aid isolation of the infectious or malignant aetiology.

If there is evidence of a leukaemic process (immature cells on the peripheral blood smear, including blasts or cells more immature than a metamyelocyte, or leukoerythroblastic changes), a bone marrow biopsy and aspirate should be obtained. The sensitivity of bone marrow findings suggesting a diagnosis in the setting of neutrophilia without immature or dysplastic cells in the peripheral circulation is low and therefore not routinely recommended.

Haematological malignancies, including CML, polycythaemia vera, and paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, as well as inflammation or infection, can each elevate leukocyte alkaline phosphatase. Using the leukocyte alkaline phosphatase level to refine the differential diagnosis of neutrophilia is thus limited by its lack of specificity. Erythropoietin levels are decreased in essential thrombocythaemia and polycythaemia rubra vera.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer