What outcomes should researchers select, collect and report in pre-eclampsia research? A qualitative study exploring the views of women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia

This article includes Author Insights, a video abstract available at https://vimeo.com/rcog/authorinsights15616

Abstract

Objective

To identify outcomes relevant to women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia.

Design

Qualitative interview study.

Setting

A national study conducted in the United Kingdom.

Sample

Purposive sample of women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia.

Methods

Thematic analysis of qualitative interview transcripts.

Results

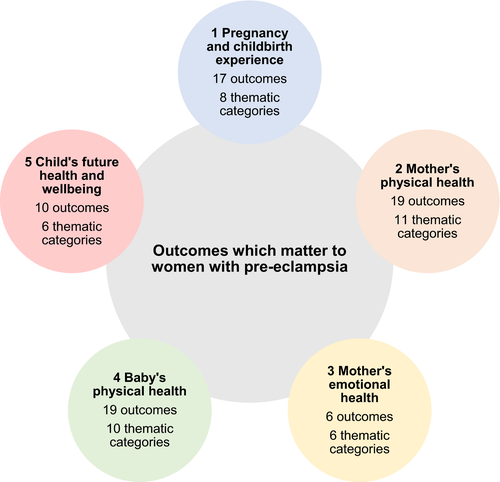

Thirty women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia were interviewed. Thematic analysis identified 71 different treatment outcomes. Fifty-nine of these had been previously reported by pre-eclampsia trials. Outcomes related to maternal and neonatal morbidity, commonly reported by pre-eclampsia trials, were frequently discussed by women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia. Twelve outcomes had not been previously reported by pre-eclampsia trials. When compared with published research, it was evident that the outlook of women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia was broader. They considered pre-eclampsia in relation to the ‘whole’ person and attached special significance to outcomes relating to emotional wellbeing and the future health, development and wellbeing of their offspring.

Conclusions

Selecting, collecting and reporting outcomes relevant to women with pre-eclampsia should ensure that future pre-eclampsia research has the necessary reach and relevance to inform clinical practice. Future core outcome set development studies should use qualitative research methods to ensure that the long list of potential core outcomes holds relevance to patients.

Tweetable abstract

What do women want? A national study identifies key treatment outcomes for women with pre-eclampsia. Next step: @coreoutcomes for #preeclampsia @NIHR_DC.

Author-Provided Video

What outcomes should researchers select, collect and report in pre‐eclampsia research? A qualitative study exploring the views of women with lived experience of pre‐eclampsia

by Duffy et al.Introduction

Randomised controlled trials evaluating potential treatments for pre-eclampsia have reported many different outcomes.1-3 Such variation contributes to an inability to compare, contrast and combine individual pre-eclampsia trials, limiting the usefulness of research to inform shared decision-making.4, 5 The development of a core outcome set for pre-eclampsia should address the variation in outcome selection, collection and reporting in randomised trials and ensure that the future evidence base is more meaningful to diverse stakeholders, including women with pre-eclampsia.6

The first stage of core outcome set development is to establish a long list of potential core outcomes.7 Previous core outcome sets in women's health have been developed by prioritising a long list of outcomes identified solely from the literature through systematic reviews of observational studies, randomised controlled trials and Cochrane systematic reviews.8 Outcomes reported in published research may not hold the same relevance for women with pre-eclampsia, particularly where research pre-dates the recent emphasis on patient and public involvement in study design.

In this study, we used qualitative research, principally the thematic analysis of in-depth interviews, to identify treatment outcomes relevant to women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia.

Methods

An advisory panel, including healthcare professionals, researchers and women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia, was established. They contributed to designing the participant recruitment strategy, sampling framework and topic guide. As the study progressed, the advisory panel was convened to discuss the participant sample, data collection and analytical focus.

Sixteen existing in-depth interviews from a University of Oxford archive (see Supplementary material, Figure S1) were included in the sample. These interviews had been conducted by experienced qualitative researchers using a comprehensive topic guide exploring lived experience, including experiences of treatment. Participants had provided explicit permission for their transcripts to be available for secondary analysis.9

Women for the new interviews were recruited through two hypertension-in-pregnancy clinics and eight national patient organisations, using a strategy designed to ensure women with assorted experiences of pre-eclampsia, from diverse demographic backgrounds and geographical locations, were included (see Supplementary material, Figure S1). Potential participants were able to register their interest by registering online, returning an expression of interest postcard, or by text message. Potential participants received a recruitment pack, which contained a plain language information leaflet, a consent form and a sampling questionnaire. The questionnaire recorded demographic details (age, ethnic group, parity and postcode) and information pertaining to their lived experiences of pre-eclampsia (gestation at diagnosis, gestation at delivery, pharmacological treatment and duration of postnatal hospital admission).

In all, 370 women registered their interest, of whom 154 potential participants completed and returned a sampling questionnaire (see Supplementary material, Figure S1, Table S1). Maximum variation sampling was used to capture a broad range of demographic characteristics and lived experience of pre-eclampsia.10 Interviews with 14 women were conducted by Dr James Duffy (Graduate Student, Balliol College, University of Oxford, United Kingdom) and included in the sample (Table 1). Dr Duffy was trained in qualitative methods and attended formal training courses including Qualitative Research Methods, Qualitative Data Analysis: Approaches and Techniques, and Analysing Qualitative Interviews.

| Interview | Age at diagnosis (years) | Age at interview (years) | (Usual) occupation | Ethnicity | Indices of deprivation (quartiles) | Parity | Gestation at diagnosis (weeks) | Mode of delivery | Another pregnancy unaffected (yes/no) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34 | 38 | Scientist | White | 1 | 1 | 40 | Ventouse delivery | No |

| 2 | 39 | 39 | Declined to disclose | White | 3 | 2 | 38 | Forceps delivery | Yes |

| 3 | 38 | 42 | Bus driver | White | 4 | 1 | 33 | Caesarean section | No |

| 4 | 24 | 25 | Midwife | White | 3 | 2 | 24 | Forceps delivery | Yes |

| 5 | 34 | 36 | Nurse | White | 1 | 1 | 28 | Ventouse delivery | No |

| 6 | 26 | 31 | Social worker | White | 3 | 1 | 40 | Forceps delivery | No |

| 7 | 29 | 36 | Teacher | White | 4 | 1 | 37 | Vaginal delivery | No |

| 8 | 37 | 38 | Marketing manager | Chinese | 3 | 2 | 38 | Caesarean section | Yes |

| 9 | 39 | 43 | Librarian | Mixed | 2 | 1 | 30 | Caesarean section | No |

| 10 | 27 | 27 | Administrator | Asian | 2 | 1 | 28 | Caesarean section | No |

| 11 | 34 | 39 | Did not disclose | White | 1 | 2 | 22 | Forceps delivery | Yes |

| 12 | 20 | 20 | Student | White | 5 | 1 | 34 | Caesarean section | No |

| 13 | 29 | 39 | Catering manager | White | 5 | 1 | 32 | Caesarean section | No |

| 14 | 35 | 41 | Researcher | White | 4 | 2 | 29 | Caesarean section | Yes |

| University of Oxford archive interviews | |||||||||

| 15 | 33 | 37 | Office manager | White | 3 | 1 | 33 | Caesarean section | No |

| 16 | 44 | 45 | Education consultant | White | 1 | 1 | 41 | Vaginal delivery | No |

| 17 | 37 | 43 | Manager | White | 3 | 1 | 32 | Caesarean section | Yes |

| 18 | 37 | 42 | Project research manager | White | 1 | 2 | 32 | Caesarean section | No |

| 19 | 33 | 33 | Business systems analyst | White | 2 | 2 | 33 | Caesarean section | No |

| 20 | 36 | 36 | Finance manager | White | 4 | 2 | 38 | Caesarean section | No |

| 21 | 37 | 40 | Operations representative | Somalian | 3 | 2 | a | a | No |

| 22 | 31 | 31 | Physiotherapist | White | 3 | 1 | 32 | Caesarean section | No |

| 23 | 34 | 35 | Teacher | White | 2 | 1 | 32 | Caesarean section | Yes |

| 24 | 31 | 32 | Management consultant | White | 5 | 1 | 29 | Caesarean section | No |

| 25 | 32 | 34 | Manager | White | 4 | 1 | 24 | Caesarean section | No |

| 26 | 35 | 40 | Nurse | Other | 4 | 2 | 29 | Caesarean section | No |

| 27 | 26 | 27 | Hairdresser | White | 2 | 2 | 28 | Caesarean section | No |

| 28 | 31 | 33 | Housewife | White | 5 | 1 | 37 | Vaginal delivery | No |

| 29 | 20 | 33 | Housewife | White | 1 | 1 | 30 | Caesarean section | Yes |

| 30 | 18 | 22 | Customer service advisor | White | 3 | 2 | 34 | Caesarean section | Yes |

- a Information not available in the University of Oxford archive.

The new interviews took place between January and October 2016. Participants were able to choose where the interview was undertaken, usually within their own home. The median interview duration was 98 minutes (range: 67–196 minutes). The initial topic guide was developed by considering the research objective, a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative literature, and additional context was provided by the study's advisory panel (see Supplementary material, Appendix S1). As the data analysis continued, the topic guide was developed iteratively to include new areas of interest. Interviews were professionally transcribed, and all transcripts were subsequently checked with reference to the audio recording.

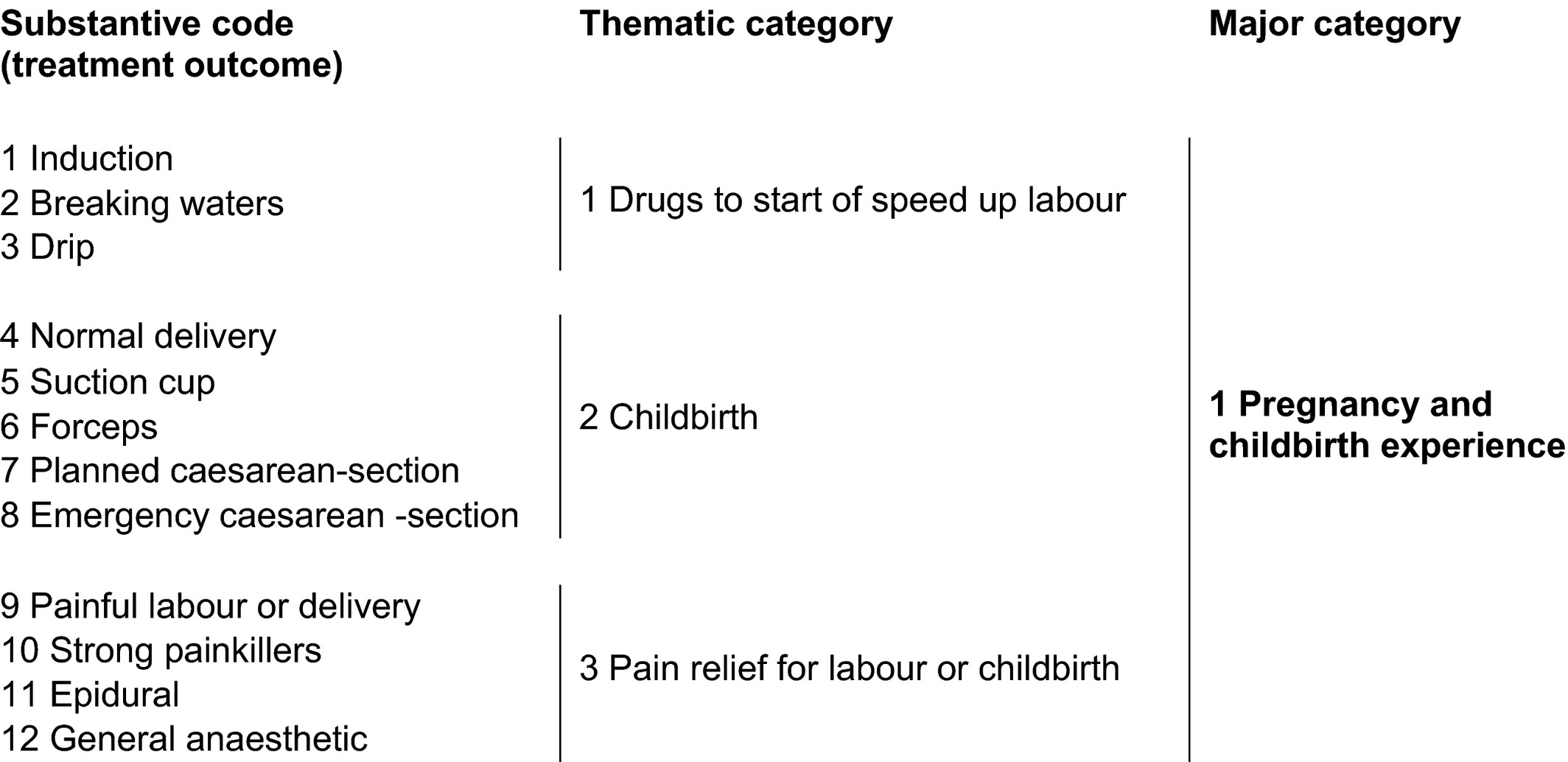

Data analysis was influenced by the approach of Corbin and Strauss to developing a coding framework.11 Each line of transcript was coded, capturing treatment outcomes anchored in the words of the participant (Table 2). A constant comparative method was used, in which each occurrence of a substantive code was compared with every other occurrence. Similar substantive codes were organised into thematic categories. Similar thematic categories were organised into major categories using NVivo 11 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Vic., Australia).

The quality of the analysis was checked by members of the steering group, including patient representatives, through comparisons in coding of diverse transcripts (triangulation). Agreement on substantive codes and categories was obtained before the analysis continued. The approach to data collection and analysis was concurrent, allowing data collection to be informed by earlier analysis.

Interviews continued until data saturation was achieved.12 As the study progressed, data saturation was assessed by the steering group by evaluating the richness of the data being collected, whether new substantive codes were being elicited, and whether new thematic categories were emerging. When saturation was considered to have been reached, a further three interviews were undertaken to confirm no new substantive codes were elicited.13

Previous systematic reviews have mapped outcome reporting across published randomised controlled trials evaluating potential treatments for pre-eclampsia.1-3 When the study was complete, the treatment outcomes identified were compared with outcomes previously reported in pre-eclampsia trials.

This is independent research arising from a doctoral fellowship (DRF-2014-07-051) supported by the National Institute for Health Research, awarded following external peer review. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Results

Thematic analysis of in-depth interviews with women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia identified 71 substantive codes (treatment outcomes). Similar substantive codes were organised into 41 thematic categories and in turn organised into five major categories (Figure 1), which are discussed below with illustrative extracts from the interviews.

Outcomes relevant to pregnancy and childbirth experience

Women described expectations, often formed before or during early pregnancy, with regards to limiting interventions during pregnancy, labour and childbirth. Many women wanted to achieve a vaginal delivery with minimal interventions and as close to full term as possible (Table 3). Pre-eclampsia often interfered with these preferences, for example when health professionals recommended induction of labour and the use of Syntocinon to increase the strength and frequency of contractions during labour.

| 1 Pregnancy and childbirth experience | |

|---|---|

| 17 substantive codes (outcomes) | Eight thematic categories |

| Natural labour | How labour started |

| Born early | Born early |

| Induction | Drugs to start or speed up labour |

| Breaking waters | |

| Drip | |

| Normal delivery | Childbirth |

| Suction cup | |

| Forceps | |

| Planned caesarean section | |

| Emergency caesarean section | |

| Painful labour or delivery | Pain relief for labour or childbirth |

| Strong painkillers | |

| Epidural | |

| General anaesthetic | |

| Intensive care | Intensive care |

| Time spent in hospital | Time spent in hospital |

| Readmission to hospital | Readmission to hospital |

“We need to get the baby out, [er] she's killing you,” well we didn't know it was a girl, “[er] she's killing you, we'll just knock you out and pull her out,” because otherwise you know my liver would have just burst through the walls.

Interview 13: 29-year-old, catering manager who described a dramatic account regarding her experiences of developing a liver capsule haematoma, a complication of pre-eclampsia.

The narratives also illustrated the special significance of achieving adequate pain relief during labour and childbirth. When confronted with situations where the effects of pre-eclampsia limited their options for pain relief, the impact on their experience was profound. Being able to use effective pain relief for labour and childbirth was described as an important outcome.

Many women described prolonged hospital admissions following childbirth because of complications associated with pre-eclampsia. Several women highlighted the substantial emotional, physical and social impact of requiring care in high dependency or intensive care settings to manage the end-organ damage associated with pre-eclampsia. Reducing the need for further interventions to manage severe morbidity was important for women and is included as a key treatment outcome.

Women said that healthcare professionals described the delivery of the baby as the ‘cure’ for pre-eclampsia. However, the women's narratives showed that delivery was sometimes only the start of the long road to recovery from pre-eclampsia. Following discharge from hospital, many women had required prolonged periods of blood pressure monitoring and treatment. Poorly controlled blood pressure occasionally resulted in readmission to hospital. Treatments capable of reducing this burden were frequently discussed.

Outcomes relevant to the mother's physical health

Understandably, women were very concerned about the life-threatening nature of pre-eclampsia. Within the interviews, women focused their attention on the consequences of pre-eclampsia across different end-organs, including brain, liver and kidneys (see Supplementary material, Table S2).

They told me that my placenta had come away and it could be because my high blood pressure [um]…blood pressure was so high that the placenta came away hence the blood that I experienced, and if they don't get the baby out quickly enough there won't be enough oxygen, and so that's how pre-eclampsia was explained to me.

Interview eight: 37-year-old marketing manager who required an emergency caesarean section at 38 weeks because of placental abruption, a complication of pre-eclampsia.

Women described the profound impact of pre-eclampsia on their ability to pursue everyday activities during and after pregnancy, for example, getting out of bed, walking and climbing stairs. This was often compounded postnatally by the mode of delivery, inpatient environment, and blood pressure monitoring and treatment. Despite being seriously unwell, many women hoped to secure a good quality of life enriched by their experiences of being a new mother. Treatments capable of reducing pain, improving sleep and increasing mobility were often discussed.

Women were aware of the importance of reducing blood pressure to prevent complications for themselves or their baby. Women were prepared to ‘put up with’ quite significant treatment side effects; the pain associated with the administration of magnesium sulphate was particularly distressing. The safety of drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding was commonly reported as a concern.

Outcomes relevant to the mother's emotional health

And so, you do, you just forget how ill I was; my kidneys didn't work right for 16 weeks after having her. I suffered through PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] through the whole experience. I didn't know that's what I had. I knew I wasn't right. I was nightmaring every night the same…woke up the hospital. It happened when she was in there; it happened for years after she was in there.

Interview three: 38-year-old bus driver who was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder 2 years after being delivered by emergency caesarean section at 33 weeks because of severe pre-eclampsia.

Several women in similar situations pursued a formal diagnosis and treatments to understand the long-term psychological impact of pre-eclampsia (see Supplementary material, Table S3). Decreasing the short-, medium- and longer-term emotional burdens of pre-eclampsia was identified as a key treatment outcome.

The impact of pre-eclampsia and its consequences often separated mothers from their babies. Women described being unable to provide skin-to-skin contact immediately following childbirth and mothers who needed specialist care sometimes being separated from their babies who required specialist care in neonatal intensive care units or special care baby units. These circumstances limited their ability to establish a bond with their baby, for example, decreasing opportunities to touch their baby and provide care. Treatments that could reduce the need for a physical separation between mothers and babies were often discussed.

Outcomes relevant to the baby's physical health

Following a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, women said that their attention rapidly turned towards the health of their baby (see Supplementary material, Table S4). The baby's movements were frequently described as a proxy for wellbeing. Reduction in movements prompted many women to seek objective reassurance regarding the health of their baby. Ultrasound measurements of wellbeing, including blood flow to the baby and baby's growth, were identified as potential key outcomes.

So, he had that, but he didn't [um]…he still wasn't responding to it, so in the end they had to put [um] a tube down his mouth; goes down straight to his [um] trachea to give that constant pressure all the time.

Interview 23: 34-year-old teacher who delivered a premature baby with respiratory distress syndrome by emergency caesarean section. Intubation was required to secure respiratory function.

Women described the consequences of disease activity for the baby's end organs. Treatments capable of reducing the physical manifestations of pre-eclampsia for the baby were often discussed.

Women who wanted to breastfeed were disappointed to be advised by healthcare professionals to formula feed, if the medications they were taking to manage severe hypertension were not safe during breastfeeding. The narratives illustrated how new mothers wanted to avoid invasive interventions and treatments, for example intubation, intravenous access and blood transfusion, for their baby.

Outcomes relevant to the child's future health and wellbeing

Heart's working, lungs are working, brain's working, ears, eyes – all the tests he was performing normally so there was nothing about him that was different to what a normal baby would be.

Interview seven: 29-year-old teacher who experienced pre-eclampsia and delivered a small-for-gestational-age baby at 37 weeks.

Comparison with outcomes reported in pre-eclampsia trials

Previous systematic reviews have mapped outcome reporting across pre-eclampsia trials.1-3 Seventy-nine pre-eclampsia trials reported 72 maternal outcomes and 47 offspring outcomes. When considering outcomes extracted from published pre-eclampsia trial reports, thematic analysis of in-depth interviews with women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia identified an additional 12 outcomes:

Maternal outcomes

- Mother and baby bonding

- Confidence being a mother

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

Neonatal outcomes

- Growth

- Intravenous access

Childhood outcomes

- Growth

- Being ‘normal’

- Achieving developmental milestones

- Educational achievement

- Disability

- Chronic lung disease

- Damage to the immune system

Discussion

Main findings

This thematic analysis of in-depth interviews of women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia identified a diverse range of 71 different outcomes, 12 of which had not been previously reported by pre-eclampsia trials.1 When compared with published research, although overlapping significantly, it was evident that the outlook of women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia was broader than that of triallists. The women considered pre-eclampsia in relation to the ‘whole’ person and attached special significance to outcomes relating to their own emotional wellbeing and the future health of their offspring.

This study has demonstrated that the outcomes reported in pre-eclampsia trials coincide with many of those that matter to women with pre-eclampsia. However, to facilitate fully informed decisions, women with pre-eclampsia require pre-eclampsia trials to collect and report outcomes that cover the psychological impact of pre-eclampsia and the future health of their offspring. Measuring the psychological impact of pre-eclampsia is likely to require the development and validation of a new measurement instrument because no specific instrument currently exists. Long-term follow-up would require difficult decisions to be made regarding the selection of long-term outcomes, how to collect the data, and the logistics and resource use involved in long-term follow up.14

Strengths and limitations

This was the first qualitative study to use the analysis of in-depth interviews to identify treatment outcomes relevant to women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia. An advisory panel, including healthcare professionals, researchers and women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia, was established to secure diverse perspectives when designing the sample framework, data collection and analytical focus. The recruitment strategy was successful: 370 women registered their interest in participating and 154 potential participants completed a sampling questionnaire. A heterogeneous sample was achieved for several important parameters including age, geographical location within the United Kingdom, socio-economic status, gestation at diagnosis, and the presence of severe features. Data collection and analysis were continued until data saturation was judged to be complete across thematic categories informed by the study's objective.

The achievement of data saturation is a subjective judgement. As the study progressed, each thematic category was reviewed by people with different perspectives, including a patient representative and experienced qualitative researchers, to assess data saturation. When data saturation was judged to have been reached, a further three interviews were undertaken to confirm no new substantive codes were being elicited. It remains possible that data saturation was not achieved, particularly for participants from minority ethnic groups who may have raised additional considerations.

Including women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia from diverse cultural backgrounds should ensure the study's findings can be generalised. Unfortunately, when considering ethnicity, the diversity achieved within the study's sample was insufficient. This was despite the recruitment strategy being redesigned to include relevant clinics that served diverse local populations, with recruitment materials translated into Bengali, Punjabi and Somali, outreach work with local advocacy groups was commenced, and the opportunity to be interviewed in another language and by a woman were both emphasised. It is not clear why these strategies failed, but it is possible that, had more women who identify as belonging to minority ethnic groups been interviewed, additional outcomes might have been identified. Future research should explore and evaluate different approaches to increasing the participation of ethnic minority groups in qualitative research studies.

Partners, families and children were not interviewed. Their inclusion could have influenced the diversity and number of treatment outcomes identified because of differences in personal perspectives, social roles and embodied lived experiences.15 Further research engaging partners, families and offspring could be valuable.

All interviews were conducted in the United Kingdom. Substantial cultural differences exist between the United Kingdom and other countries, including diverse models of healthcare provision, different approaches to the management of pre-eclampsia, and distinctive attitudes regarding health and wellbeing.16 Such differences might influence the perceptions of women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia and may also affect which outcomes matter to them. Further research should establish to what extent the outcomes identified in this study apply to women with pre-eclampsia residing in different countries, including low- and middle-income settings.

Interpretation: recommendations for future core outcome set developers

Different methodological choices could influence the identification of potential core outcomes.17 Many core outcome set development studies have published systematic reviews of randomised trials and observation studies.18-23 This study has demonstrated that thematic analysis of in-depth interviews as an effective method to ensure a long list of potential core outcome holds relevance to patients. Secondary analysis of interviews within the University of Oxford archive successfully contributed to this study.9 Other potentially less resource intensive data collection and analysis methods, including solely the secondary analysis of archive interviews, focus groups or free text questionnaires could also be useful. There is limited research to inform the effectiveness of these different approaches in the context of core outcome set development.24 Although many core outcome sets relevant to maternal and newborn health are in development, a small minority have used formal qualitative research methods.6, 25-29 Researchers have successfully analysed data collected during focus groups with children and teenagers with neuro-disability to identify relevant treatment outcomes.30 Future core outcome set developers should consider establishing research evaluating different qualitative data collection and analysis methods to determine treatment outcomes pertinent to patients.

There is currently insufficient research to understand the relationship between the potential core outcomes entered into a consensus development method and the core outcome set eventually developed. The modified Delphi method is commonly used to identify consensus ‘core’ outcomes and enables participants to suggest additional outcomes to be entered into the consensus development process. Further research is required to determine whether outcomes suggested by participants within the consensus development process could address any deficiencies in the methods used to develop a long list of potential core outcomes or even make specific methods redundant. Until the position is clarified, future core outcome set developers need to demonstrate that their long list of possible core outcomes holds relevance to patients. Ensuring a patient-centred approach to core outcome set development should ensure that future core outcome sets improve the quality of future research and reduce unintended research waste.31, 32

Conclusion

Selecting, collecting and reporting outcomes relevant to women with pre-eclampsia should ensure that future pre-eclampsia research has the necessary reach and relevance to inform clinical practice. Developing, disseminating and implementing a core outcome set for pre-eclampsia should ensure future pre-eclampsia research selects, collects and reports outcomes that matter to women with pre-eclampsia. This approach is recommended for others developing core outcome sets for pregnancy and childbirth research.

Disclosure of interests

Prof Richard J. McManus has received blood pressure monitors for research from Omron. The remaining authors report no conflict of interests. Completed disclosure of interest forms are available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

Study concept and design was by JMD, RMcM and SZ. Acquisition of data was by JMD, LH and MS. Analysis and interpretation of data was by JMD, TT, RMcM and SZ. JMD drafted the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was by TT, LH, MS, RMcM and SZ, and JMD, SZ and RMcM obtained funding.

Details of ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service Committee South Central ethics committee (reference number: 12/SC/0495; date of approval 13 June 2014).

Funding

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This report is independent research arising from a doctoral fellowship (DRF-2014-07-051) supported by the National Institute for Health Research. Prof. Richard McManus is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-R2-12-015) and the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Oxford. Prof. Sue Ziebland is a National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

We would like to thank the women who participated in this study. We would like to thank the Radcliffe Women's Health Patient Participation group, Action on Pre-eclampsia, and our patient and public representatives who assisted with study design, data interpretation and planned dissemination. We would like to thank Prof. Louise Locock, Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, who conducted several interviews contained within the University of Oxford Archive; Prof. Khalid Khan, Queen Mary, University of London who assisted with securing study funding; and Romola Watts for transcribing the interviews. We would like to thank colleagues at the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford including Jacqui Belcher, Carla Betts, Lucy Curtin, Dawn Evans, Caroline Jordan, Sarah King, Sam Monaghan, Dan Richards-Doran, Nicola Small, and Clare Wickings for administrative, technical and material support. We would like to thank colleagues at the Women's Health Research Unit, Queen Mary, University of London including Tracy Holtham and Rehan Khan for administrative and technical support, and subject-specific expertise. We would like to thank David J. Mills for administrative and material support.

Appendix: International Collaboration to Harmonise Outcomes in Pre-eclampsia (iHOPE) Qualitative Research Group

Dr James M. N. Duffy (Balliol College, University of Oxford, United Kingdom); Ann Marie Barnard (Action on Pre-eclampsia, United Kingdom); Carole Crawford (University of Oxford, United Kingdom); Tracey Dennis (patient representative); Dr Lisa Hinton (Health Experiences Research Group, University of Oxford, United Kingdom); Dr Mark Johnson (University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation, United Kingdom); Mr Rehan-Uddin Khan (Queen Mary, University of London, United Kingdom); Lisa Newhouse (Kicks Count, United Kingdom); Mehali Patel (Bliss, United Kingdom); Dr Gurmukh Sandhu (Nottingham University Hospital NHS Trust, United Kingdom); Teresa Shalofsky (University of the West of England, United Kingdom); Louisa Waite (BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, United Kingdom); Dr Mathew Wilson (University of Sheffield, United Kingdom); Prof. Khalid S. Khan (Queen Mary, University of London, United Kingdom); Prof. Richard J. McManus (Green Templeton College, University of Oxford, United Kingdom); and Prof. Sue Ziebland (Green Templeton College, University of Oxford, United Kingdom).