Dynamic Field Theory of Executive Function: Identifying Early Neurocognitive Markers

Citation Information: McCraw, A., Sullivan, J., Lowery, K., Eddings, R., Heim, H. R., & Buss, A. T. (2024). Dynamic field theory of executive function: Identifying early neurocognitive markers. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 89(3).

Abstract

In this Monograph, we explored neurocognitive predictors of executive function (EF) development in a cohort of children followed longitudinally from 30 to 54 months of age. We tested predictions of a dynamic field model that explains development in a benchmark measure of EF development, the dimensional change card sort (DCCS) task. This is a rule-use task that measures children's ability to switch between sorting cards by shape or color rules. A key developmental mechanism in the model is that dimensional label learning drives EF development.

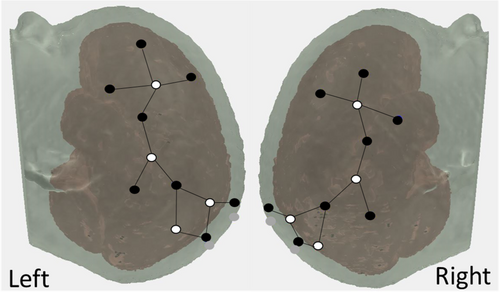

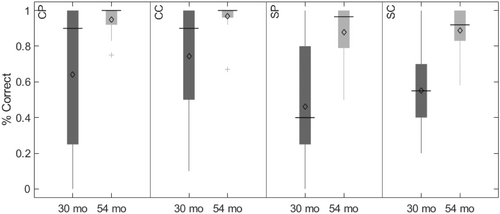

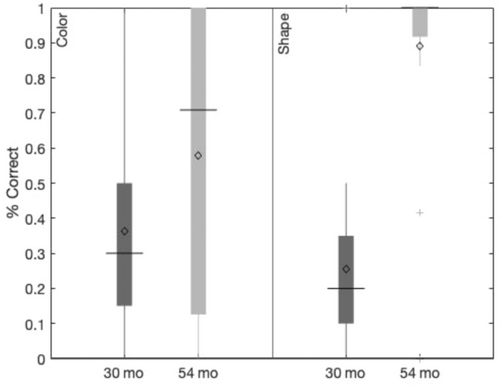

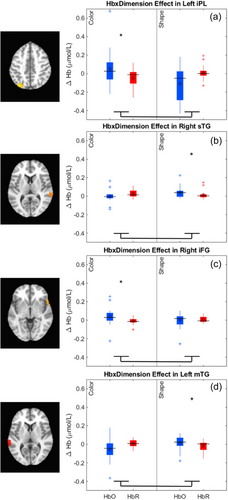

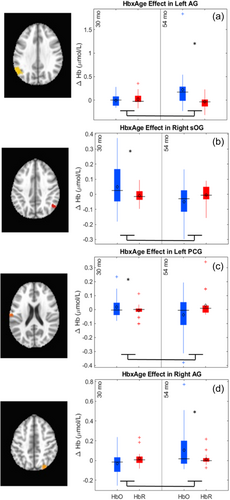

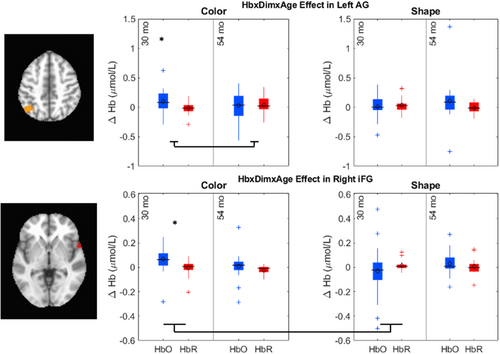

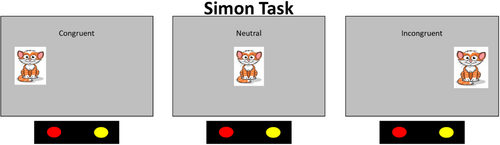

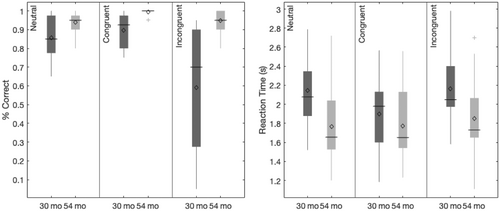

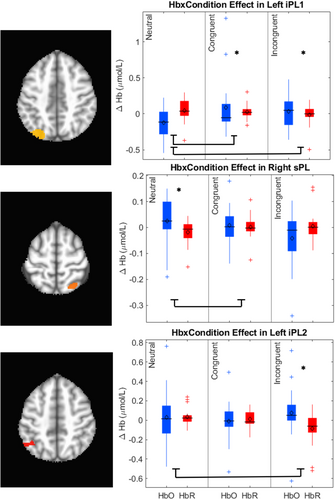

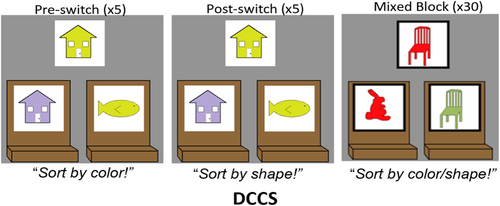

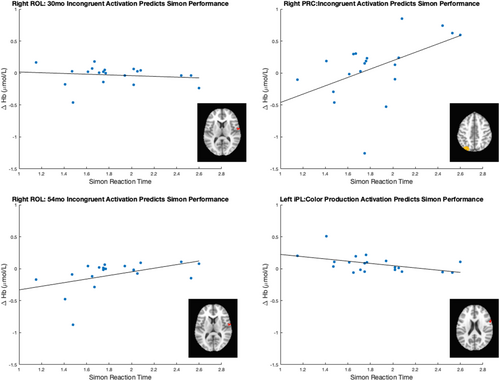

Data collection began in February 2019 and was completed in April 2022 on the Knoxville campus of the University of Tennessee. Our cohort included 20 children (13 female) all of whom were White (not Hispanic/Latinx) from an urban area in southern United States, and the sample annual family income distribution ranged from low to high (most families falling between $40,000 and 59,000 per year (note that we address issues of generalizability and the small sample size throughout the monograph)). We tested the influence of dimensional label learning on DCCS performance by longitudinally assessing neurocognitive function across multiple domains at 30 and 54 months of age. We measured dimensional label learning with comprehension and production tasks for shape and color labels. Simple EF was measured with the Simon task which required children to respond to images of a cat or dog with a lateralized (left/right) button press. Response conflict was manipulated in this task based on the spatial location of the stimulus which could be neutral (central), congruent, or incongruent with the spatial lateralization of the response. Dimensional understanding was measured with an object matching task requiring children to generalize similarity between objects that matched within the dimensions of color or shape. We first identified neural measures associated with performance and development on each of these tasks. We then examined which of these measures predicted performance on the DCCS task at 54 months. We measured neural activity with functional near-infrared spectroscopy across bilateral frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices.

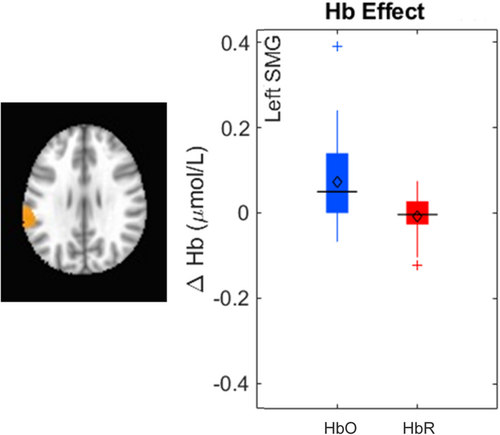

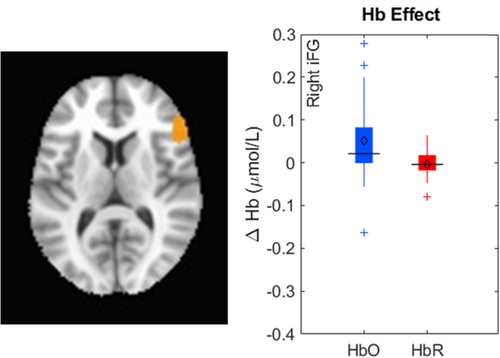

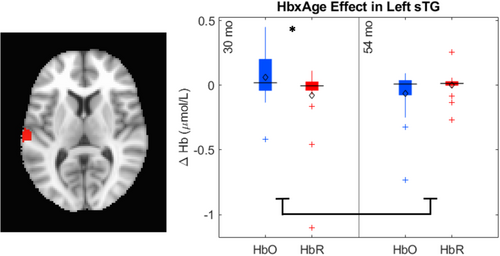

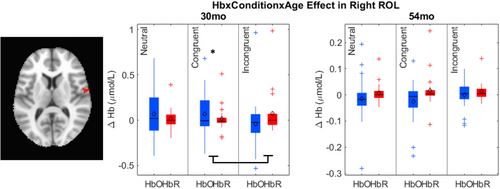

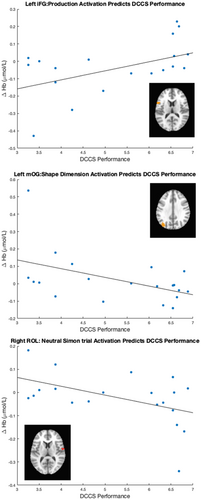

Our results identified an array of neurocognitive mechanisms associated with development within each domain we assessed. Importantly, our results suggest that dimensional label learning impacts the development of EF. Neural activation in left frontal cortex during dimensional label production at 30 months of age predicted EF performance at 54 months of age. We discussed these results in the context of efforts to train EF with broad transfer. We also discussed a new autonomy-centered EF framework. The dynamic field model on which we have motivated the current research makes decisions autonomously and various factors can influence the types of decisions that the model makes. In this way, EF is a property of neurocognitive dynamics, which can be influenced by individual factors and contextual effects. We also discuss how this conceptual framework can generalize beyond the specific example of dimensional label learning and DCCS performance to other aspects of EF and how this framework can help to understand how EF unfolds in unique individual, cultural, and contextual factors.

Measures of EF during early childhood are associated with a wide range of development outcomes, including academic skills and quality of life. The hope is that broad aspects of development can be improved by implementing interventions aimed at facilitating EF development. However, this promise has been largely unrealized. Previous work on EF development has been limited by a focus on EF components, such as inhibition, working memory, and switching. Similarly, intervention research has focused on practicing EF tasks that target these specific components of EF. While performance typically improves on the practiced task, improvement rarely generalizes to other EF tasks or other developmental outcomes. The current work is unique because we looked beyond EF itself to identify the lower-level learning processes that predict EF development. Indeed, the results of this study identify the first learning mechanism involved in the development of EF.

Although the work here provides new targets for interventions in future work, there are also important limitations. First, our sample is not representative of the underlying population of children in the United States under the age of 5. This is a problem in much of the existing developmental cognitive neuroscience research. We discussed challenges to the generalizability of our findings to the population at large. This is particularly important given that our theory is largely contextual, suggesting that children's unique experiences with learning labels for visual dimensions will impact EF development. Second, we identified a learning mechanism to target in future intervention research; however, it is not clear whether such interventions would benefit all children or how to identify children who would benefit most from such interventions. We also discuss prospective lines of research that can address these limitations, such as targeting families that are typically underrepresented in research, expanding longitudinal studies to examine longer term outcomes such as school-readiness and academic skills, and using the dynamic field (DF) model to systematically explore how exposure to objects and labels can optimize the neural representations underlying dimensional label learning. Future work remains to understand how such learning processes come to define the contextually and culturally specific skills that emerge over development and how these skills lay the foundation for broad developmental trajectories.

I Theoretical Issues in the Development of Executive Function (EF)

Introduction: Defining the Problem of EF Development

One of the most striking aspects of early cognitive development is the emergence of children's ability to control and regulate their behavior in a goal-directed manner (Blair et al., 2005). These abilities are typically attributed to a set of skills that are collectively referred to as EF. EF is needed in a wide range of situations, such as when a context has a salient stimulus that is not goal appropriate. For example, a classroom contains stimuli associated with an array of behaviors. Sometimes those behaviors need to be inhibited, such as playing with a friend during quiet story time. Sometimes different behaviors should be engaged in different contexts, such as playing with toys during free time, but also putting those toys away at the end of free time. EF abilities are also crucial when a prepotent behavior is no longer appropriate and a new behavior needs to be selected—such as when the child is playing red light/green light and must stop running toward their peer when “red light” is shouted—or when multiple behaviors are potentially relevant but only one is appropriate for currently represented goals—for example when selecting which marker to use to color a tree. Yet in other times, children need to think flexibly about the nature of objects they interact with. For example, they may need to switch from using a marker to color a tree to using that same marker to roll out some Play-Doh. In this case, the child is focusing on the color of the object in one context but the shape of the object in another context.

Across these examples, children structure their behaviors (e.g., playing with a friend or sitting quietly) and their cognitive processes (e.g., using attention to select specific aspects of the environment that they are remembering or representing) to accommodate goal directed behavior. In the laboratory setting, children can perform simple skills such as inhibiting an immediately desired behavior (e.g., eating a snack) as early as age 2. By age 5, children can typically display more complex abilities such as alternating between different behavioral rules (e.g., sort cards by shape or color; Carlson, 2005). Much research has been directed at uncovering not just the different types of EF skills that children develop, but also how those skills impact broad development outcomes, such as quality-of-life and academic skills. For instance, measures of EF during early childhood are associated with health, wealth, and criminal offending outcomes three and four decades later (Moffitt et al., 2011; Richmond-Rakerd et al., 2021). Moreover, lab-based measures of EF are also associated with socio-emotional competencies (Raver et al., 2011) and better predict math and literacy achievement than IQ (Ahmed et al., 2021, 2019; Blair et al., 2005; Bull et al., 2008; Cortés Pascual et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2012; Robson et al., 2020; Santana et al., 2022; Spiegel et al., 2021; St Clair-Thompson & Gathercole, 2006; Swanson et al., 2008). Thus, EF skills are important for how individuals make decisions that can support long-term goals and how receptive children are to learning environments. For these reasons, EF is a common target in intervention studies aimed at improving developmental trajectories across a wide range of outcomes.

Many aspects of children's experiences are known to influence EF, such as socioeconomic status (SES) and culture. That is, higher SES is typically associated with better EF (Hackman et al., 2015). Although this effect has been replicated cross-culturally (Fernald et al., 2011), different rates of EF development across cultures have also been documented. For example, EF was shown to develop more rapidly in a sample of Hong Kong adolescents relative to their counterparts in the United Kingdom, but adult levels of EF did not differ between cultures (Ellefson et al., 2017). Other research has demonstrated cultural differences in the relative impact of SES on EF development. In one study, measures of early childhood EF were compared across the SES gradient between a low- to middle-income country (South Africa) and a high-income country (Australia). Although EF increased across SES quintiles within samples from each country, participants from the lowest SES quintiles in the low- to middle-income country (South Africa) outperformed individuals from the highest quintile in the high-income country (Australia; Howard et al., 2020). While these findings illustrate that the gradient effect of SES on EF generalizes across cultures, it also highlights that the behaviors and structures across cultures can influence EF development in unique ways. Thus, it is also important to consider how structure of child care, social interactions, values, and norms within different cultures (e.g., Madhavan & Gross, 2013) can foster the formation of EF processes. Thus, income levels within a country or culture are not the only factor influencing developmental outcomes related to EF. Rather, EF can be impacted by the interactive influence of culture and SES.

Other factors associated with differences in EF performance include race, ethnicity, or cultural background. All typically developing children will get better on EF tasks with age, but these age-related improvements are stronger in White children than in African American children (Assari, 2020). African American and Hispanic children often enter Kindergarten with lower scores on EF tests (Little, 2017), though these students typically catch up to their peers as school progresses, suggesting that early education experiences do help close the gaps between these students. However, EF tests show racial/ethnic disparities even into adulthood (Rea-Sandin et al., 2021). Such results should be interpreted with caution, however. The nature of these differences are likely due to differences in children's structured experiences or opportunities for learning across these sociocultural factors. In general, there have historically been economic, racial, and ethnic disparities in educational opportunity and resources, beginning in early childhood (Fram & Kim, 2012). However, it is also important to consider the nature of EF measures. In many ways, EF enables competent and healthy behavior in cultural activities. Across measures of cognitive function, not just EF, scales are typically developed and tested on primarily White and middle-class children. Indeed, it has recently been suggested that we need to take a different approach to assessing EF that is sensitive to the unique ways that participating in organized behaviors varies cross-culturally (Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023). We return to discussion of this critical issue in Chapter VIII.

SES and cultural influences are high dimensional and complex, which presents challenges for understanding the exact role of experience on EF development. Nevertheless, these findings demonstrate that EF development is a malleable process. Our goal in this monograph is to provide evidence for how children's early neurocognitive development lays the foundation for later EF development so that more specific aspects of children's experiences can be targeted in future intervention work.

Guide for Reading This Monograph and Overview of Chapters

In this first chapter, we describe the current prevailing theories of EF development and highlight the limitations of these theories to identify mechanisms of EF that can be used to improve broad developmental outcomes. Briefly, the primary challenge facing theories of EF development is to strike a balance between generality and specificity. EF inherently operates at a general level: EFs should be able to regulate behavior across a range of contexts and behaviors. For example, inhibiting the behavior of playing with a friend during story time at school likely relies upon similar skills used to stay seated at the table during dinner time. However, EF needs to also be grounded in children's experiences so that we can begin to understand how learning impacts EF development and how EF skills are connected to the specific details of each context.

In Chapter II we describe EF through the lens of dynamic field (DF) theory (Schoner et al., 2016), a computational approach that uses neural population dynamics to explain cognition, behavior, and neural function. In this chapter we provide technical details of the modeling framework and step through examples illustrating the computational properties of the model. However, we also include a Conceptual Summary of the model at the end that is accessible to a more general audience. Briefly, neural population dynamics refers simply to the way that groups of neurons interact with each other to create behavior. The DF model can address the primary challenges of explaining EF development because neural populations in the model are tuned to dimensions of the perception-action system. Previous work (Buss & Kerr-German, 2019; Buss & Spencer, 2014, 2018) has demonstrated that this framework can explain a wide range of behavioral and neural data on the development of EF and makes predictions that have been supported by empirical data. In the DF model, EF is a property of neural population dynamics rather than a structural component of the cognitive system. The key insight provided by this framework is that dimensional label-learning (e.g., forming associations between labels such as “red” and “color” with the visual feature dimension of color) fosters object-based attention skills that can explain developmental improvement on key measures of EF. In the DF model, forming associations between labels and visual dimensions builds neural connections that can be used to enhance processing of visual feature information that is represented as goal relevant. In this way, the model illustrates how label learning can help children make sense of their perception/action systems and to guide the processing of information to achieve goals in a flexible manner across diverse contexts.

Chapters III through VII describe a longitudinal study that assessed the neurocognitive function across a broad range of cognitive domains between 30 and 54 months of age. Note that Chapter III provides the technical details of the study, including data processing and analyses, in addition to the details of the sample of children included in the study. Chapters IV through VI each include an opening paragraph describing the content of the chapter and a conclusion section which can stand alone to provide a summary of the primary information contained in each chapter.

The goal of the current study was to identify which measures of neurocognitive function are predictive of EF at 54 months of age. Specifically, we tested the central prediction of the DF model that label learning will impact the development of EF. Thus, we measured neurocognitive function across the domains of dimensional label comprehension and production (Chapter IV), dimensional understanding and categorization (Chapter V), and simple EF tasks (Chapter VI) at 30 months. We then identified the neurocognitive measures that were predictive of EF at 54 months of age (Chapter VII). To preview, our results suggest that dimensional label learning is the best predictor of future EF development and changes in the neural systems involved in dimensional label production account for individual variability in a benchmark measure of EF skills. Moreover, the predictive nature of these measures generalizes across the contexts of both complex and simple measures of EF. In Chapter VIII we summarize the overall results of our study and discuss these findings within the broader context of EF development.

Prevailing Theories of EF

EF was first identified in neuropsychological research involving patients with damage to the frontal cortex. Although these individuals had relatively preserved cognitive functions, they had severe difficulty regulating these cognitive functions or controlling impulses (Duncan, 1986; Lhermitte et al., 1972; Luria, 1973). At its early conception, EF was characterized as a singular function which guided behavior to achieve goal-directed behavior. Various influential theories proliferated that incorporated such a central executive to explain a wide range of skilled behavior (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Norman & Shallice, 1986). These views, however, were noted for their limitation in explaining EF because control processes were carried out by an unspecified “central executive” or “control homunculus” that was aware of task goals and the means to achieve them. Thus, these views described the types of functions that fell under the scope of EF and when such functions were needed but did not explain how they were actually carried out.

More recent approaches to EF have attempted to “fractionate” the control system (Monsell & Driver, 2000) by identifying smaller EF components or mechanisms that are involved in goal-directed behavior. The most common components include, but are not limited to, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive switching. Inhibitory control is defined as the ability to suppress behaviors and cognitive processes that are irrelevant or inappropriate for currently represented goals; working memory is defined as the capacity to manipulate or update actively represented information that can be used to guide future behaviors and decisions; and cognitive switching is defined as the ability to update ongoing cognitive processes and representations when goals or contexts change. The various forms of controlled and goal-directed behavior that are observed in both lab and real-world settings are thought to arise through the use and combination of such EF components.

This component-based view of EF is supported by research using factor-analysis approaches that identify associations between measures of performance on tasks that involve EF. Work with young adults and children has shown that measures of EF load onto factors that can be mapped onto concepts such as inhibition, working memory, or switching. In a seminal study of young adults, Miyake and colleagues (2000) administered a battery of nine “simple” EF tasks that were designed to measure specific components of EF (three tasks each targeting inhibition, working memory, or switching). These tasks have task demands that require only a single EF component. For example, hearing a list of numbers and repeating them requires only the EF component of working memory. Additional tasks were also administered that were designed to be “complex” measures of EF that required more elaborate cognitive processing (e.g., the tower of Hanoi and the Wisconsin card sort). These tasks have additional task demands beyond the engagement of a single EF component. For example, the Wisconsin card sort requires participants to hold in mind categorical information about the sorting cards, learn through trial and error which sorting rule to use, and inhibit the urge to sort based on rules from previous trials. Factor analyses showed that the tasks targeting specific EF components loaded onto common factors (e.g., the three tasks targeting inhibitory control uniquely loaded onto a single factor together). Moreover, these factors also predicted performance on “complex” EF tasks. For example, the tower of Hanoi task was predicted by the latent factor corresponding to the inhibition component and the Wisconsin card sort task was predicted by the factor corresponding to the switching component. Interestingly, not all of the complex tasks were predicted by a latent factor, suggesting that the sampling of tasks in this study did not comprehensively assess all possible EF components. These initial findings, however, gave traction to the idea that EF can be parcellated into smaller component processes.

Developmental research has applied similar factor analysis approaches to demonstrate that children's performance on EF tasks show similar associations to those that parcellate EF with adult participants. Moreover, the complexity of children's EF increases over development, such that measures of children's EF initially load onto a single factor and gradually differentiate to load onto two and eventually the three-factor structure seen in young adulthood (Agostino et al., 2010; Fuhs & Day, 2011; Huizinga et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2013; Lehto et al., 2003; McAuley & White, 2011; Rose et al., 2011; Shing et al., 2010; van der Sluis et al., 2007; Van der Ven et al., 2012; Wiebe et al., 2008; Willoughby et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2011). It is also important to note that this latent variable approach has yielded inconsistent results regarding the differentiation of EF components over development, suggesting that the structure revealed by this statistical approach depends upon the tasks being administered and the dependent variables that are measured from those tasks (Miller et al., 2012).

The structural component view is appealing because it decomposes complex behavior into simpler functions. Moreover, these components provide a way of explaining domain-general skills that create the capacity to control behavior beyond the details of a particular task (Zelazo & Carlson, 2023). Generally, this view aligns with findings that specific and overlapping neural processes underlie a wide variety of tasks designed to measure EF ability. That is, EF tasks often vary in terms of specific task content, yet they activate similar frontotemporal regions that presumably support an overarching EF system that is defined independently of the processes and domains over which control is being exerted. This is because these domain-specific abilities are needed in many other non-EF tasks and yet do not activate the frontotemporal regions in the way that EF tasks do.

Criticisms of the Component View

There are, however, many criticisms against characterizing EF in terms of components. One is that these constructs are largely defined by the tasks used to assess them. Thus, these theoretical constructs do not go beyond simply describing the processing required by the task. This is particularly problematic in developmental work in which the developmental explanation is conflated with the cognitive description. For example, it is theoretically circular to say improvement on an inhibitory control task is due to growth in the inhibitory control component (for discussion see Morton, 2010; Munakata et al., 2003). Second, EF components are conceptualized as domain-general functions that are defined independently of the informational content in a task or context. Conceptualized in this way, EF components can be used to explain behavior across contexts, but this conceptualization leads to issues when considering the mechanisms that create developmental changes. Specifically, the abstract nature of EF components presents challenges when considering how these components can interface with the details of contexts in which control must be exerted. By drawing such a sharp distinction between the EF component and the information being regulated, there is little opportunity for children's learning or experiences to impact the quality of EF. Indeed, the prevailing theories of EF development propose that maturational processes give rise to growth in EF skills with little consideration of the role of learning (Bunge & Zelazo, 2006; Fiske & Holmboe, 2019; Moriguchi & Hiraki, 2009). Thus, the generalizability of EF components comes at the expense of being able to consider how EF can be built from children's experiences and opportunities for learning.

The component view of EF is also challenged by empirical data on interventions aimed at improving EF. Because it is well-established that EF is an essential skill set and measures of EF during early childhood are predictive of future success (e.g., academic achievement), identifying targets for intervention that can yield broad transfer is a research priority. These efforts have focused training on tasks that engage specific EF components such as practicing an inhibitory control task; however, these efforts have not led to broad generalization. For example, lab-based interventions aimed at building EF have shown improvements on the targeted EF domain (e.g., inhibitory control abilities), but not other EFs (e.g., working memory, cognitive switching) (Enge et al., 2014; Morrison & Chein, 2011). Moreover, these domain-specific improvements often do not generalize to the real-world behavior or different lab-based tasks (Aksayli et al., 2019; De Simoni & von Bastian, 2018; Friese et al., 2017; Gobet & Sala, 2023; Jacob & Parkinson, 2015; Kassai et al., 2019; Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013; Melby-Lervåg et al., 2016; Nesbitt & Farran, 2021; Rapport et al., 2013; Sala & Gobet, 2019; Shipstead, Hicks, et al., 2012; Shipstead, Redick, et al., 2012; Simons et al., 2016; Takacs & Kassai, 2019). These results challenge the notion that EF is composed of these structural components and motivate a reconceptualization of EF. Our strategy in the current work is to look outside the domains that are typically considered EF to determine the role that dimensional label learning plays in cultivating EF skills.

Measuring EF Development With The Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS) Task

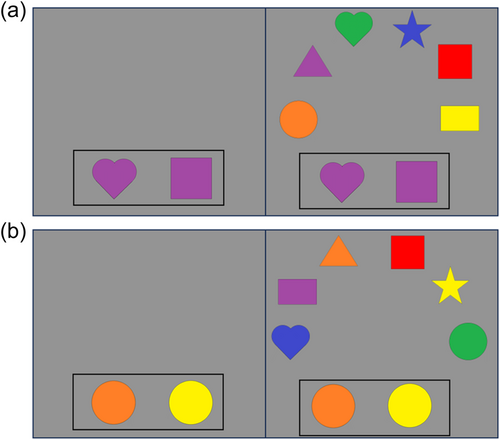

EF follows a protracted developmental time course. The time between ages 2 and 5 is particularly important, however, as this period sees the emergence and refinement of many new EF skills. A wide variety of tasks have been developed to assess different aspects of EF in the lab (e.g., Carlson, 2005); however, one task that has emerged as a benchmark measure of the developmental status of EF is the DCCS task (Zelazo et al., 2003). This task involves using two separate feature dimensions—color and shape—to sort objects. Participants are first instructed to sort by one feature dimension (the pre-switch dimension) for a series of trials and then to switch to sort by the other dimension (the post-switch dimension). This task has garnered attention in the literature due to the dramatic shift in performance over development. Most 3-year-olds will fail to switch rules despite continuous reminders that the rules have changed whereas most 4-year-olds will have little difficulty switching rules (Zelazo et al., 2003). Thus, between the ages of 3 and 5, children's EF undergoes critical developmental change which confers the ability to switch rules in this task.

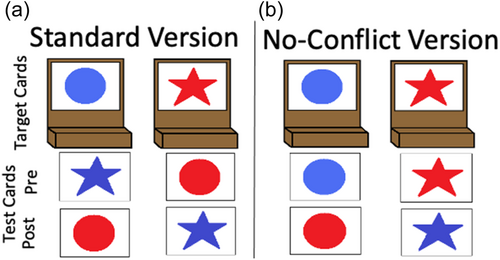

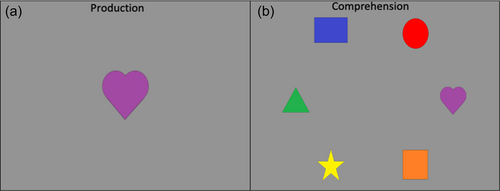

The DCCS task can be characterized as having relatively straightforward demands on rule-switching because children are directly instructed on which rules to use for sorting. This contrasts with other tasks that either involve multiple sequences of rule-switch and rule-repeat trials (Rogers & Monsell, 1995) or tasks that require participants to infer rule switches based on feedback (Chelune & Baer, 1986). Consideration of the task details, however, illustrates the complex nature of cognitive operations required to switch rules. First, the DCCS task uses target cards that are affixed to the location where children sort cards. These target cards provide visual structure that show which features should be sorted to which location for the shape and color rules, for example, a blue circle and a red star (see Figure 1a). Second, the test cards that children sort match both target cards along different dimensions, for example, a blue star and a red circle (see Figure 1a). Thus, children must selectively attend to the relevant dimension and inhibit attention to the irrelevant dimension to match a test card to the correct sorting location. Third, children must hold in working memory the currently relevant rules to sort by color or shape. Fourth, habits accumulate during the initial sorting phase that both enhance the strength of representation of one dimension and weaken the strength of representation of the other dimension. For example, if sorting by color during the initial sorting phase, then the representation of the color dimension would be more strongly represented than the shape dimension after the initial sorting phase is completed. When children are instructed to sort by shape during the post-switch phase, it is necessary to use EF resources to overcome the imbalance in representational strength across dimensions. Thus, this task presents multiple challenges that the cognitive system must resolve.

Recently, this task has been expanded in the NIH Toolbox to provide a graded measure of EF abilities beyond early childhood in a way that is more informative than just the binary pass/fail outcome reported in the original task. The new scoring system integrates reaction times and accuracy to create a more holistic DCCS performance score. This is made possible via the NIH Cognition Toolbox's (Zelazo et al., 2013) inclusion of a block of trials in which the rules are mixed. This block is administered if the post-switch phase is completed successfully. This mixed block is structured so that participants are cued on one-third of the trials to sort by the pre-switch rules and are cued on two-thirds of trials to sort by the post-switch rules. Performance can then be scored in terms of both accuracy and reaction time, providing a continuous metric of EF skills.

Neural Mechanisms of EF in the DCCS Task

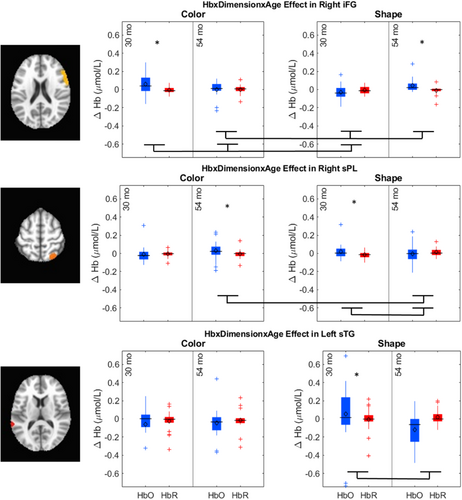

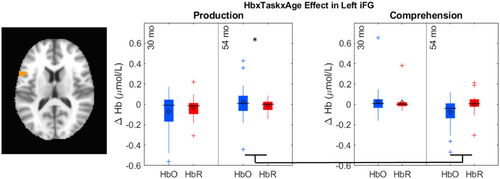

Many previous studies have found associations between the development of EF skills and neural activity. Moriguchi and Hiraki (2009) found that preschool age children who switched rules showed stronger frontal cortex activation while completing the DCCS task compared to children who failed to switch rules. These results are typically interpreted as evidence that brain maturation leads to the ability to activate this brain region, which then causes the development of the ability to regulate behavior (Bunge & Zelazo, 2006). Other studies, however, have demonstrated that manipulations to the DCCS task can impact the ability of children to switch rules and engage the frontal cortex. As discussed above, the DCCS provides visual cues, referred to as target cards, to indicate which features are to be sorted at the two locations for each task. The test cards that children sort are configured such that they match both target cards along different dimensions. As shown in Figure 1a, the target cards are a red circle and a blue star, but the two test cards are a red star and a blue circle. This configuration creates attentional conflict that requires selective attention to focus processing on the task-relevant dimension. This conflict can be eliminated by having children sort test cards that match the target cards along both dimensions. For example, the no-conflict version in Figure 1b shows the test cards during the pre-switch phase as a red circle and a blue star, which match the images on the target cards. Standard conflict cards are used during the post-switch phase. In this condition, most 3-year-olds can successfully switch rules (Müller et al., 2006; Zelazo et al., 2003).

Buss and Spencer (2018) examined neural activation across the standard DCCS task and the no-conflict DCCS task using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Results from this study showed that children who failed to switch in the standard DCCS task, and showed weak frontal cortex activation when doing so, nevertheless showed strong frontal cortex activation when correctly switching rules in the no-conflict version of the task. Thus, activation in frontal cortex and the ability to switch rules is not only influenced by developmental status but also by children's experiences in the task. That is, the same children that supposedly had an “immature” frontal cortex as evidenced by a lack of activation during the standard task, showed stronger activation when correctly switching rules in an easier version of the task. This finding suggests that frontal activation is not limited by the developmental status of this brain region but is also influenced by children's learning within a task.

Explanations of Developmental Changes in Performance on the DCCS Task

The componential view of EF has had a strong influence on theories of EF development. For example, theories of development in the DCCS task have focused on some combination of the inhibition, working memory, and cognitive control components to explain developmental changes in performance on this task (Brace et al., 2006; Diamond et al., 2005; Zelazo, 2004). The most influential of these theories is cognitive complexity and control (CCC) theory put forth by Zelazo and colleagues (Zelazo, 2004; Zelazo et al., 2003). This theory is grounded in rule-representation processes that are implemented as production rules such as “if it is red, then sort to this location” and “if it is a circle, then sort to this location.” In this case, rules that are used gain a higher level of saliency whereas rules that conflict with the rules currently being used are suppressed to lower levels of activation. When instructed to switch to the post-switch rules, children's representation of the rule for sorting by shape (e.g., “if it is a circle, then sort to this location”) will be more weakly represented relative to the representation of the rule for sorting by color (e.g., “if it is red, then sort to this location”). The development of rule-use abilities is the result of increases in the complexity of rules that children can represent. More complex rule-representations allow children to behave flexibly based on a nested hierarchy of representations. For example, to succeed in the DCCS task, children could use a production rule such as, “if I am playing the color game, and if it is blue, then sort here; but if I am playing the shape game, and if it is a circle, then sort there.” With this production rule, children can make decisions for an object (a blue circle) based on different properties of that object. Without the ability to nest multiple if statements, children will persist in using the more strongly activated rule (i.e., the initial sorting rule) rather than switching to the new rules. Increases in the complexity of rule representation are mediated by changes in the level of representation (referred to in this theoretical perspective as a level of consciousness) that children can attain. By taking time to reflect on the nature of the problem, children achieve higher levels of representation in which greater complexity of rule-representations can be supported. Mechanistically, children progress to higher levels of complexity of rule representation and LOC as the frontal cortex matures (Bunge & Zelazo, 2006).

New Conceptualizations of EF

More recent ideas about EF development, however, have pushed back against a rigid component structure to characterize EF in terms of the processes involved in cognitive control that are inherently contextual. Doebel (2020) describes an alternative perspective in which EF is not a set of separable skills but instead a more general ability to use self-control. That is, Doebel (2020) proposes that there are not multiple EFs, but instead the emerging ability to use self-control that is tied to the details of the specific context in which children are behaving. Here, the emphasis is on the child's conceptual structure (e.g., acquired knowledge, values, beliefs, preferences, etc.) that are relevant in a particular context and to which they can ground their use of cognitive control. Thus, the ability to use self-control will depend on the other factors involved in the context of the task, the child's environment, and the child's previous experience. To the extent that lab-based measures predict behavior in other tasks or outside of the lab, this is due to the overlap in underlying concepts across measures.

Bardikoff and Sabbagh (2021) recently offered an example of such an approach in which they proposed that developmental improvement of performance on the DCCS task is grounded in a conceptual and abstract understanding of dimensionality. When applied to the DCCS task, this object-based approach posits that the objects involved in the task—the shapes and colors–are more important for successful completion than the rules of the task—sorting by shape and color. In this sense, the emphasis is on the representational content of the task. Representational content refers to the information involved in the task that the child will use to complete the task goals. In this case, the representational content is a conceptual understanding that objects are composed of separable dimensions. Thus, success in the DCCS task hinges on children's conceptual understanding of dimensionality which allows children to use cognitive control to flexibly sort objects.

Bardikoff and Sabbagh (2021) tested the role of dimensionality understanding on DCCS performance by training children on multidimensionality prior to completion of the DCCS. The training consisted of a game where children were shown a black-and-white outline of a shape and a colored blob. Children were then instructed to select a colored shape, combining the shape outline and the colored blob. Training on both the relevant feature dimensions (the dimensions used in the canonical DCCS task, color and shape) and irrelevant feature dimensions (in this study, the pattern of an object) lead to better performance on the canonical DCCS task in preschool-aged children. Thus, Bardikoff and Sabbagh (2021) interpreted these data as indicating that training children on the multidimensionality of objects impacted children's ability to think flexibly about the nature of objects so that they could flexibly apply different sets of rules.

Limitations of Current EF Theories

Although these new proposals are noteworthy for shifting away from traditional ideas about EF, two important challenges still linger. First, these proposals do not resolve the tension between generality and specificity because the emphasis is now on the context rather than the domain general cognitive control skill. Thus, the main issue is to specify how the emerging capacity for cognitive control connects to variations in context or children's underlying conceptual structures. Doebel's proposal avoids reification of EF into components by suggesting that EF is comprised of a set of skills whose use depends upon contextual information and factors intrinsic to the child; however, Doebel's proposal also falls short by not specifying how these skills are used in context-specific ways. Because this perspective is a verbally specified theory, accounting for such a complex interaction and the range of factors that could potentially influence the use of control is a daunting task.

Second, these new proposals do not specify how cognitive control is impacted by learning and children's experiences. For example, Bardikoff and Sabbagh (2021) argue that an understanding of dimensionality impacts a child's performance on the DCCS task. Dimensional understanding is described as an abstract form of representation that exerts top-down control on cognitive processing. This perspective, however, does not specify the link between children's experiences and conceptual structure, nor the link between abstract understanding of dimensionality and the processes of representing and making decisions about multi-dimensional objects.

To address these challenges, Perone and colleagues (2021) argue that theories should focus on how control becomes a property of a neurocognitive system rather than on skills or components that are used in the service of control. In this regard, dynamic systems theory provides the concepts of self-organization and autonomy, which can provide new traction to the study of EF. Specifically, when components of a system are coupled to one another, it is possible for the system to behave in ways that are not programmed into the system but are a product of interactions between components (Thelen & Smith, 1994). Such organization arises in a neural system as populations of neurons tuned to dimensions of perception and action interact with one another. These interactions can result in the formation of stable neural states that drive behavior. In the context of the DCCS task, for example, neurons that encode both the color red and the shape star interact and become coupled with neurons that drive the action to sort the card. Moreover, quantitative changes in the properties of these neural populations and how they interact with one another can produce qualitative change in both neural activity and behavior. In other words, the dynamic systems approach addresses the key shortcomings associated with other theories of EF development by providing the tools to think about autonomy in a principled fashion and linking the types of changes brought about through learning and experience to the emergence of EF skills. In this Monograph, we focus on one specific instantiation of a dynamic systems theory called dynamic field (DF) theory (Chapter II).

Conclusion: Reconceptualizing EF Development to Include Autonomy

EF is critically important in a broad array of developmental outcomes. Yet, empirical and theoretical work have yet to capitalize on the centrality of EF. This work has been hampered by the inability to identify developmental mechanisms related to EF development. Consequently, intervention research has failed to improve developmental trajectories by directly training aspects of EF. Historically, concepts surrounding EF have been limited due to the inherent nature of EF which revolves around issues of autonomy and self-organization. Descriptions of EF centered on components of EF struggle to explain how such components develop in ways that are not self-referential. More recent conceptualization centered on the context-dependent nature of EF struggle in different ways to link learning of specific information to variable contexts in which EF is achieved. To address these persistent issues in the study of EF, the approach in our study is to further explore the predictions of a neurodynamical model (a DF model). Specifically, this model looks beyond EF itself to identify learning-based mechanisms of development. This work shows how a learning process that associates labels with visual features can explain the development of EF. As labels are learned for visual features and dimensions, multimodal representations are built that provide neurocognitive mechanisms for directing attention to task- or goal-relevant features of objects. As label representations are strengthened in the model, aspects of EF are displayed as properties of neural interactions. In the next chapter, we discuss the computational properties of this model, highlighting how the model builds EF processes from perception-action systems involved in object representation and label learning. We summarize the empirical support for this model and outline the specific predictions that we aimed to test in the current study. This chapter (Chapter II) also concludes with a conceptual summary of the DF model for readers not familiar with computational approaches to neurocognitive development.

II EF Through the Lens of DF Theory

Introduction to DF Theory

In this chapter, we describe a neurocomputational model grounded in dynamic field (DF) theory. DF models have been used to replicate human data in numerous studies of both children and adults across several tasks of EF and word learning (Schoner et al., 2016). In DF theory, behavior arises from interactions between populations of neurons that are either excitatory or inhibitory. For example, a neuron that responds to the blue hue will increase the activation of other neurons that also prefer the blue hue and inhibit activation from neighboring neurons that respond to other hues. These interactions between neurons are what eventually drive an individual's behavior.

The model is composed of two primary systems. An object representation system builds representations of multi-feature objects (e.g., a red star) within neural populations that are tuned to visual features and spatial location. An object representation arises as a pattern of activation for visual features within different visual dimensions (e.g., color and shape) along the spatial dimension. The model also includes a label representation system. This system implements processes related to word learning by forming associations between labels (e.g., “red” or “color”) and visual features (e.g., the red hue) and dimensions (e.g., color). The dimensional labeling system is reciprocally coupled with the object representation system such that activation for visual features can be boosted by activating labels (and vice versa). In this way, the model can use its understanding of labels to prioritize task-relevant visual information and follow rules. The stronger the connection between labels and visual features, the better the model performs on the DCCS task. Thus, the primary developmental mechanism implicated by the model is a label learning process. Conceptually, as children's neural representations of shape and color labels improve, performance improves on the DCCS task.

DF theory has been extensively applied to explain and predict children's behavioral responses and neural activation across various findings from the DCCS and other tasks (Buss & Kerr-German, 2019; Buss & Spencer, 2014, 2018; Perone et al., 2015, 2019). This DF model frames EF around object-based attention. Specifically, performance is a result of the ability to prioritize the processing of perceptual information based on task goals. Instead of viewing action as a consequence of a “central executive” or homuncular control system, the DF model demonstrates how cognitive control is an emergent property of interactions between neurocognitive systems and the environment. Importantly, this computational framework provides a means of quantifying properties of the neurocognitive system and the various contextual factors as they relate to behavior and development. In this context, rather than EF being defined in terms of structural components such as inhibition or switching, EF is instead defined as a property of how label representations guide object-based attention. Across various projects, the DF model has provided a rigorous quantitative explanation of behavioral and neural development across a range of different task demands.

Model Architecture and Dynamics

DF models are built with populations of neurons that are tuned to metric dimensions of perception (e.g., color) and action (e.g., spatial direction of a planned action). Such metric dimensions of neural tuning have been widely reported in various neurophysiological studies (Erlhagen et al., 1999; Jancke et al., 1999; Markounikau et al., 2010). These neural populations interact through local excitation and lateral inhibition tuning profiles. This means that activation of one neuron may either decrease or increase activation of the neurons connected to it depending on the feature preferences of those other neurons. If one neuron is activated for a particular hue of color such as red, for example, it may share excitation with neurons that respond to similar hues. While this neuron is enhancing activation via direct excitatory connections, it also inhibits others through the process of lateral inhibition that is mediated by inhibitory interneurons. For example, another neuron in the population may activate in response to a different color, such as blue. While the neuron that reacts to red is activated, the neuron that is responsive to blue receives inhibitory input. This pattern of excitation and inhibition make it possible for neurons to produce the stable neural states that are needed to drive behavior: local-excitation enhances activation of neurons participating in a representation while lateral-inhibition suppresses other neurons. Stability is an important dynamic because neurons receive noisy inputs from the world and from other neurons to which they are connected. Neural states must have a mechanism to protect against these sources of noise so that a representation can be maintained over time to drive a behavior. This pattern of neural connectivity provides a general mechanism by which neural populations can produce such stable and self-sustaining states (Schoner et al., 2016).

DF models make a strong commitment to embodiment by using neural populations tuned to dimensions of perception and action. That is, the models are built around the interface of the body with the environment, grounding representations in sensory surfaces and dimensions of the motor system. DF models, however, are not limited to simple perceptual and motor representations. These dimensions can be combined in DF models that build more elaborate and abstracted representations, as we will describe below. By combining dimensions of perception/action representations, models can perform complex tasks such as building representations of multi-feature objects (Johnson et al., 2008), making sorting decisions as in the DCCS (Buss & Spencer, 2014), searching for visual objects in a cluttered scene (Grieben et al., 2020), or learning words (Bhat et al., 2022). Thus, DF theory explains behavior through the interactions within and between populations of neurons and through these interactions, it is possible to produce more complex or abstract representations.

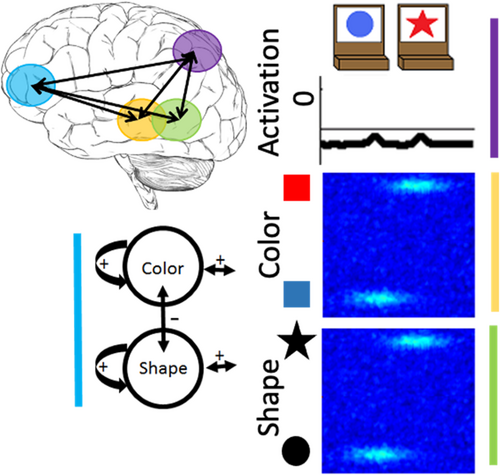

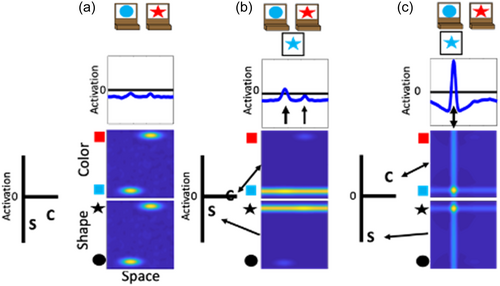

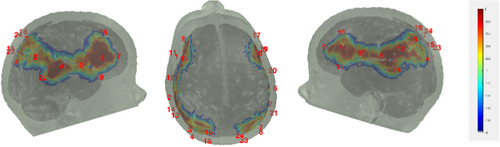

We have previously developed a DF model that simulates a wide range of behavioral findings with the DCCS task; made predictions about behavior in novel variations of the DCCS task (Buss & Spencer, 2014); simulated neural activation and made novel predictions about neural activation (Buss & Spencer, 2018); generalized to explain developmental changes in a set of other tasks involving categorization and priming (Buss & Kerr-German, 2019); and predicted the impact of prior exposure to perceptual dimensions (Perone et al., 2015, 2019). The model architecture includes an object representation system. In this system, there are three fields: (1) a spatial motor planning field corresponding to processing within the parietal cortex, a (2) color-space field, and (3) a shape-space field corresponding to processing within the temporal cortex (Figure 2). The model builds representations of objects by binding feature dimensions to a common spatial frame of reference. Thus, the color-space and shape-space field are composed of neural units that have a joint preference for a visual feature and a spatial location. These fields are reciprocally coupled to the spatial motor planning field. That is, the color-space and shape-space fields send excitatory activity to the spatial motor planning field, and the spatial motor planning field sends excitatory information back to the shape-space and color-space fields. Lastly, each field has an inhibitory layer which provides lateral inhibitory input at the location of activation within each field. As discussed above, the inhibitory population is needed to stabilize activation of a peak and to force selective activation dynamics. That is, through lateral inhibition, each field is only able to form a peak at a single location.

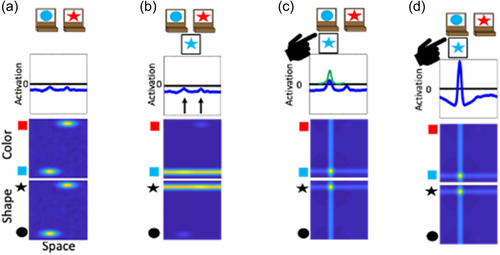

To illustrate the dynamics and interactions that produce object representations in the context of the DCCS task, Figure 3 displays the sequence of events during a trial in which the experimenter sorts a card to a tray to demonstrate the color rules. First, in Panel a each field has inputs corresponding to the locations of the features on the target cards. In the spatial field, there are two sub-threshold inputs at the leftward and rightward locations. In the color-space field, there are sub-threshold inputs for blue at the left and red at the right. Similarly, in the shape-space field there are sub-threshold inputs for circle on the left and star on the right. In Panel b, the model is illustrated shortly after a test-card is presented to the model. In this example, the model is shown a blue star. The features blue and star within the color- and shape-space fields are ridges of input across the entire spatial dimension. At this point, there is no information about the spatial localization of these features in the context of the task-space. In Panel c, the model is shown after the spatial demonstration of sorting this card to the leftward location. Of note, there is a strong spatial input to the leftward location in the spatial field (plotted in the green line). This is creating ridges of input at the leftward spatial location across the color- and shape-space fields. Finally, in Panel d the model is shown after the formation of the object representation is complete. Here, the model now has peaks of activation across all three fields at the leftward spatial location. That is, the model has activated the blue feature and star feature at the leftward spatial location to represent the sorting of the blue star object to the leftward location.

In the above example, the experimenter provides the spatial location information (illustrated as the green input line at the leftward spatial location) needed to overcome the spatial conflict between features on the test card. That is, the blue feature overlaps with the target card input at the leftward location, whereas the star feature overlaps with the target card input at the rightward location. A second component is needed for the model to overcome this imbalance and sort in an autonomous fashion. Specifically, the model also contains a dimensional label system corresponding to processing in the frontal cortex (see Figure 2). This system is simplified as a two-neuron system that has a representation of the label “color” and the label “shape.” These neurons are reciprocally coupled to the color-space and shape-space field, respectively. The model is “instructed” to sort by a particular dimension by providing an input that boosts baseline activity for the relevant label neuron. For example, in Figure 4 the model is instructed to sort by color and the color label neuron is at a higher resting level than the shape label neuron. When a test card input is presented to the model and activation builds within the color- and shape-space fields, excitation is sent to the dimensional label neurons as illustrated by the arrows in panel B. The color label neuron reaches the activation threshold more rapidly than the shape label neuron. At this point, the color label neuron begins to contribute excitation globally to the color-space field as illustrated by the double-sided arrow. The arrow illustrating interactions between the shape-label neuron and the shape-space field is one-sided because the shape neuron is receiving excitation from the shape-space field but is not near the activation threshold to send excitation back to the shape-space field. With the color-space field boosted, the input to the spatial field is receiving stronger excitation at the leftward spatial location. This imbalance in input is due to the overlap between the ridge of input from the test card and the localized input for the blue feature on the target card at the leftward spatial location. Finally, in Panel c the model has built a peak of activation in the leftward location in the spatial field, reflecting the decision of the model to sort to the left sorting tray. As a result, the spatial field has stabilized this object representation by sending ridges of spatial excitation to the color- and shape-space fields, forming peaks for the color blue and the shape star at the leftward location. Moreover, local excitation and lateral inhibition interactions have increased the activation of the color neuron far above the activation threshold. The activation of the color label neuron is suppressing the activity of the shape label neuron. The model is, thus, “attending” to the color dimension. Although this figure only provides snap-shots in time, these dynamics play out in real-time as activation cascades through the network.

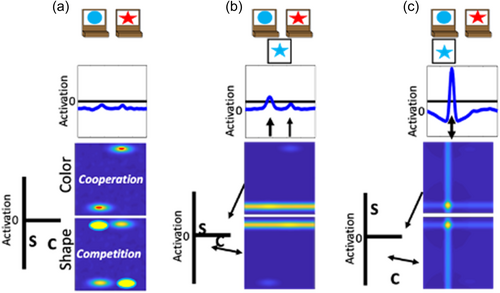

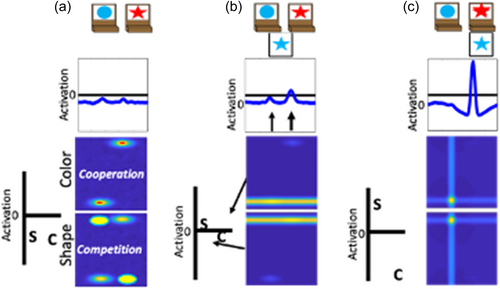

A key element to the model's explanation of performance across the different variations of the DCCS task is the formation of memory traces for specific feature-space conjunctions. In the examples above, the model was sorted by color. But the model, just like a human, is incapable of making a decision about the color of an object without also binding that decision to the object's shape. Based on the conjunction of features on the test cards, the model builds memory traces that link the blue and star features to the leftward location within their respective feature-space fields. In addition, the model also builds memory traces that link the red and circle features to the rightward location within their respective feature-space fields. Memory traces are lasting neural representations of the object features in space. Functionally, these traces increase the resting level of neurons so that they are closer to their activation threshold and require less input to become activated. These neural representations create a stronger influence on activation states as they are further reinforced by repeated trials. Because the model sorted by color, the memory traces within the color-space field will align with the inputs from the target cards. In this case, the color-space field will be more sensitive for the red feature at the rightward location and the blue feature at the leftward location because those locations are now closer to the activation threshold. However, within the shape-space field, the memory traces will be at the opposite location of the target card inputs (note the yellow ovals in Panel a of Figures 5 and 6). In this case, the star and circle features will experience lateral inhibition based on the sensitivity to both spatial locations for these features.

Previous work has demonstrated that the performance of the model on the DCCS is impacted by the strength of coupling between label neurons and feature-space fields (Buss & Kerr-German, 2019). With weak coupling, as illustrated in Figure 5, the model perseverates. In Panel a, the shape label neuron is now boosted through the instruction input (telling the model to sort by shape) and is closer to the activation threshold than the color label neuron. In Panel b, a test card is presented as in the previous examples. In this case, however, the correct response would be to sort to the rightward location because the red feature is located on the target card on the right. As can be seen in the spatial field, however, there is more input being sent to the leftward location due to the combination of memory traces across the shape- and color-space fields at this spatial location. As a result, the model sorts this test card to the leftward location as shown in Panel c. This decision is made despite the model correctly engaging activation of the shape label neuron. This failure represents the behavior that a young child would show and is the result of weaker coupling between feature labels (“color” or “shape”) and the feature dimension (color and shape).

With stronger coupling, as illustrated in Figure 6, the model correctly updates its behavior and matches by shape. In this figure, the model is given the same test card as in Figure 6 and the correct response would be to sort to the rightward location. In Panel b, however, there is now stronger activation at the rightward location in the spatial field. This is due to the stronger boosting of the shape-space field. The input for the star feature overlaps with the target card input at the rightward location. The target card inputs are stronger than the memory traces. Thus, the star feature is closer to threshold at the rightward location than the leftward location. By more strongly engaging activation of the shape-space field, the rightward spatial location is now more strongly activated than the leftward spatial location in the spatial field. As a result, the model correctly selects the rightward location as shown in Panel c.

Distributions of parameter values were generated for the strength of coupling between label neurons and feature-space fields and individual parameter values from these distributions were applied to individual runs of the model. Over a population of model simulations each with its own unique parameter settings, the model reproduced the pattern of behavior of 3- and 4-year-olds across a wide range of variations in the DCCS task. This includes situations in which perseveration of 3-year-olds persists despite manipulations to visual features between the pre- and post-switch phases as well as manipulations that improve the performance of 3-year-olds. Moreover, the model has been used to predict the behavior of children in new versions of the task that manipulate the spatial structure between the pre- and post-switch phases (Buss & Spencer, 2014). The model also explains the brain-behavior relationship by simulating the increase in frontal cortex activity observed for children that switch rules compared to children who fail to switch rules. In this context, the model also generated predictions that children who perseverate in the standard task, and show weak frontal cortex activation when doing so, nonetheless show strong frontal cortex activation when correctly switching in an “easier” version of the task. This difference in activation between conditions within the same children is a result of memory traces aligning with the target card inputs within the feature-space field that is relevant for the post-switch phase. This alignment between target inputs and memory traces creates a stronger input from the feature-space fields to the dimensional label neurons, thus increasing the activation in this component of the model that corresponds to the frontal cortex (Buss & Spencer, 2018). Lastly, the model is not a special-purpose EF model. It generalizes to explain performance on other tasks that do not explicitly involve the use of verbal rules or labels (Buss & Kerr-German, 2019). That is, the same model operating under the same parameters can generalize to explain performance on categorization and priming tasks simply based on changes to the input that reflects the details of these other tasks.

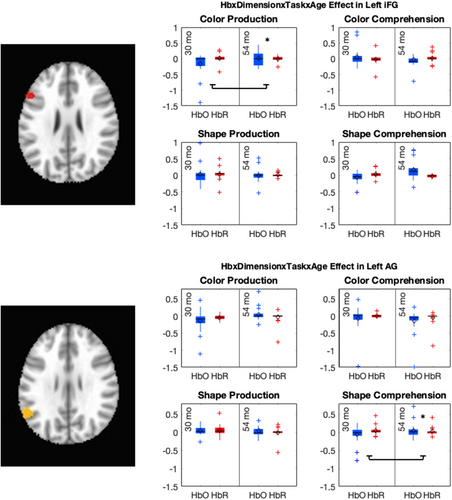

The key novel aspect of the DF model is the grounding of rule-use in object representation and label learning processes. We have previously published data showing that dimensional label learning impacts the development of EF (Lowery et al., 2022). A prediction of the DF model is that measures of dimensional label learning should be related to performance on EF tasks that involve attention to visual dimensions, such as the DCCS task, but not on other measures of EF that do not have this task demand. For example, the flanker task assesses spatial attention and should be unrelated to the dynamics involved in dimensional label learning. In the flanker task, children are instructed to attend to an arrow in the center of the screen and execute a left/right button response based on the direction that the arrow is pointing (i.e., press the leftward button if the central arrow is pointing left and press the rightward button if the central arrow is pointing right). Participants are typically slower and more error-prone when the flanking stimuli are pointing in the opposite direction as the central stimulus (Rueda et al., 2004). Because this task does not involve any dimensional labeling like the DCCS does, it would not be expected that dimensional labeling abilities would affect performance. We previously conducted a longitudinal study comparing dimensional label production and comprehension to the DCCS and flanker tasks. We found that activation in left middle frontal gyrus during dimensional label production at 33 months of age was positively associated with performance on the DCCS task at 45 months of age, but was unrelated to any aspect of performance on the flanker task (Lowery et al., 2022). That is, the more strongly participants activated this region at 33 months of age during dimensional label production, the better they performed on the DCCS task a year later. This evidence suggests that the neural mechanisms supporting dimensional label comprehension and production also generalize to impact performance on specific measures of EF. This study by Lowery and colleagues provides a breakthrough in how we understand EF development but has several limitations regarding methods and results. Most importantly, this study administered the dimensional label learning (DLL) task at 33 months but not again at 45 months. Because of this, we cannot assess the growth in dimensional labeling abilities in the children and cannot relate this growth to individual differences in DCCS performances at 45 months. The current study administered the DLL task at both 30 and 54 months, allowing us to measure this growth in labeling ability from child to child.

How DF Theory Explains EF Development

The DF model can relate to various aspects of previous theories and debates surrounding the development of EF. As argued by Doebel (2020), the conceptual representations required by a task impact the ability of children to exert control. In the context of the DF model's explanation of the DCCS task, the relevant conceptual structures are dimensional label representations. In contrast to Doebel's proposal, however, control is situated within the dynamics of an autonomously behaving neurocognitive model. In this sense, control is a property of the neurocognitive system. Also similar to the argument put forth by Zelazo and Carlson (2023), there is value in having domain-general cognitive skills that can transfer across contexts. In this case, dimensional label representations can be used in any number of contexts to guide attention to visual dimensions. As illustrated by Buss and Kerr-German (2019), dimensional label representations have also been used to explain associations in performance on a priming and a categorization task that do not involve explicit use of verbal labels. Lastly, in relation to the dimensional understanding explanation, the DF model provides a way of grounding dimensional understanding in a label learning process. The primary result from Bardikoff and Sabbagh's (2021) multidimensionality training is that training on the separability of visual dimensions that comprise objects conferred a benefit to subsequent performance. This finding suggests that performance on the DCCS involves a general understanding of the dimensional nature of objects. The key distinction between these explanations is that the notion of dimensional attention provided by the DF model is grounded in children's learning about label representations, visual features, and visual dimensions. The implementation of these processes provides a formalized explanation across a wide range of manipulations to the objects and contexts involved in the DCCS task. The notion of dimensional understanding in Bardikoff and Sabbagh's (2021) perspective, however, is grounded in an abstract conceptual understanding of the separability of dimensions which was manipulated in their task by providing experiences with separated and integrated dimensions. By highlighting the multiple dimensions of objects as in their task, children's representations of dimensions may have been boosted via memory traces, making it less imperative that the child has a strong representation of object-features and their labels.

DCCS and EF: The Influence of Language

The DF model suggests that label learning plays a central role in performance on the DCCS task. Previous work has demonstrated the influence of labels on DCCS performance. For example, Yerys and Munakata (2006) showed that children were better at switching if the pre-switch was instructed with generic language, such as playing a “sorting” game rather than the “color” game. Moreover, children were also better at switching if novel features with novel labels were used during the pre-switch phase. In both cases, the lack of specific or familiar language during the pre-switch phase builds up a weaker bias for the pre-switch dimension. In another line of work, Buss and Nikam (2020) showed that the label “shape” is much less frequent than “color” in the CHILDES database, a database of recordings of verbal interactions between children and their caregivers (MacWhinney, 2000). They then tested 4-year-olds, who would typically pass the DCCS, in a new version of the DCCS that only provided the labels “shape” or “color” during the instructions. For example, children were told, “We're going to play the shape game. Put this shape here (pointing to one target card) and this shape there (pointing to the other target card).” Children perseverated at a significantly higher rate when switching to shape if only the label “shape” was used in the instructions. This finding suggests that the quality of learning for specific labels impacts how well children can use those labels to guide attention.

Beyond the DCCS, various other lines of work have identified language effects on EF measures. There is often a bilingual advantage on measures of EF (Bialystok & Martin, 2004; Poulin-Dubois et al., 2011), suggesting that learning multiple languages facilitates EF skills. This finding, however, is controversial because the association between bilingualism and EF varies based on the cultural context from which bilinguals are sampled or whether potential confounds are accounted for in analyses (Dick et al., 2019). Linking the effects of label learning and SES, previous research has also demonstrated a profound language input difference across SES. Research has identified an effect commonly referred to as “the 30 million-word gap,” in which children from low SES backgrounds receive significantly less language input (Golinkoff et al., 2019). This finding could indicate a mechanistic relationship between language and EF that can be moderated by factors such as SES. As we reviewed above in the context of the CHILDES database, the relative frequency of specific labels, in this case “color” and “shape,” impacts performance on EF tasks. Thus, global differences in language input are likely to also be associated with differences in dimensional label input and, relatedly, measures of EF development.

Cognitive control abilities and dimensional attention are also evident in non-human primates that do not have language abilities (Beran et al., 2016). It is important to point out, however, that such performance requires extensive training to associate cues with visual dimensions. In many ways this is consistent with the framework sketched out the DF model. Language is not a special process in the model; rather, the attentional function of language is a byproduct of associating representations across different perceptual dimensions. Thus, training non-human primates to attend to visual dimensions, for example, would be the result of artificial associations between cues and visual dimensions which are a natural product of label learning.

DF models also provide potential avenues to think about how factors such as SES and culture influence the developmental trajectories of EF. Bhat et al. (2022) recently developed the word-object learning via visual exploration in space (WOLVES) model, which is an expanded DF model that autonomously learns labels through cross-situational exposure to labels and objects. In other words, WOLVES represents the ways that language can both affect and be affected by perception of the child's enviornment. This framework provides an opportunity to probe how exposure to language structures the representations that children come to use for EF skills. WOLVES may, then, be able to explain how unique aspects of children's learning can create individual differences in children's development in relation to cultural or SES factors.

Conclusions: Model Summary and the Current Study

In the current research project, we more comprehensively explored the relationship between dimensional label learning and EF. The current project builds upon a decade of theory development which has formulated a DF model that explains a wide range of findings with the DCCS, predicted children's performance in novel conditions of the DCCS, predicted the impact of prior exposure to shape and color dimensions, simulated developmental changes in hemodynamic responses, and predicted patterns of neural activation in novel conditions. Across all these different findings, the unifying explanation is that dimensional label learning contributes to the development of EF and generalizes to not only explain and predict behavioral data, but also explains and predicts patterns of neural activation over development. No other theory achieves nearly this level of quantitative explanation of data. Very little work, however, has identified the neural mechanisms of dimensional label learning and their impact on EF development.

In the previous project by Lowery et al. (2022), we examined whether dimensional label learning uniquely predicts DCCS performance among other measures of EF outcomes. However, this project did not assess changes in neurocognitive function associated with dimensional label learning nor did it assess changes in neurocognitive function across other domains. In the current project, we again addressed this question but also asked whether DCCS performance is best predicted by dimensional label learning compared to other factors (i.e., simple EF and dimensional understanding). The goal of the current study was to identify the mechanisms underlying EF development and to determine which measurements from these tasks at 30 months predict EF ability at 54 months. A key developmental mechanism in the model is a label learning processes which cultivates neural representations that can organize decision-making around visual feature dimensions.

Thus, our primary hypothesis is that neural signatures of dimensional label comprehension and production will predict the future development of EF skills. In other words, we expect neural responses during dimensional label tasks to reflect the quality of neural representations supporting dimensional label learning. These neural responses measured at 30 months should be predictive of performance on the DCCS task at 54 months.

In contrast, other theories have proposed that EF develops via maturational growth (Bunge & Zelazo, 2006; Diamond, 2002). In this case, we might expect that later EF development would be better predicted by early measures of EF. That is, if EF is organized around components that undergo maturational changes over development, then measuring the developmental status of simple EF at earlier points in development should best predict later developmental status of complex EF. We used the Simon task to test this alternative viewpoint. This task was chosen because it has similar arbitrary response selection demands to the DCCS but is simpler so that younger children could perform it. In the Simon task, children need to ignore or inhibit the spatial location of a stimulus which can interfere with the spatial location of a response.

Lastly, another recent proposal reviewed above suggests that children develop an abstract understanding of dimensionality which gives rise to flexibility on the DCCS task (Bardikoff & Sabbagh, 2021). Specifically, previous research on dimensional label learning has examined children's ability to categorize by color or shape using a dimensional matching task that does not use dimensional labels but instead requires children to generalize “sameness” within shape or color dimensions (Sandhofer & Smith, 1999). Thus, we also measured neurocognitive function during this task to determine whether the understanding of dimensionality would predict development of EF skills. The next five chapters present data from a longitudinal study that was aimed at identifying early precursors of later EF.

III General Methods and Analyses

The current chapter focuses on the general methods and analytical procedures used in this study. Data comes from a longitudinal study in which children were initially recruited at 30 months of age and came back at 54 months of age. Participants were recruited beginning in February 2019 and data collection was completed in April 2022. Data collection was also planned when participants were 42 months of age; however, it was during this time that in-person research activities were halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of this, we were not able to bring children in for the 42-month sessions but were able to bring back 21 children for their 54-month sessions.

Participants