Understanding heterogeneity in pathways between interparental conflict and children's involvement: The moderating role of affect-biased attention

Morgan J. Thompson was affiliated with the University of Rochester at the time this research was conducted and is currently affiliated with Auburn University.

Abstract

The study examined the moderating role of children's affect-biased attention to angry, fearful, and sad adult faces in the link between interparental conflict and children's distinct forms of involvement. Participants included 243 preschool children (Mage = 4.60 years, 56% female) and their parents from racially (48% African American, 43% White) and socioeconomically (median annual household income = $36,000) diverse backgrounds. Data collection took place in the Northeastern United States (2010–2014). Utilizing a multi-method, multi-informant, longitudinal design, attention away from anger selectively amplified the link between interparental conflict and children's subsequent coercive involvement (β = −.15). Greater attention to fear potentiated the pathway between interparental conflict and children's later cautious (β = .14) and caregiving involvement (β = .15). Findings are interpreted in the context of environmental sensitivity models.

Abbreviations

-

- AOI

-

- areas of interest

-

- CFI

-

- comparative fit index

-

- FIML

-

- full-information maximum likelihood

-

- GED

-

- general education diploma

-

- ICC

-

- intraclass correlation coefficient

-

- IDI

-

- Interparental Disagreement Interview

-

- PoI

-

- proportion of interaction

-

- RMSEA

-

- root mean square error of approximation

Children's involvement in interparental conflict reflects their behavioral efforts to mediate or intervene in parental disputes (Rhoades, 2008). Recent empirical work indicates that there may be developmental and clinical value in examining involvement as a multi-dimensional construct. Utilizing thematic analysis, Thompson, Davies, Hentges, et al. (2021) identified three distinct involvement strategies during early childhood, including coercive (i.e., authoritarian pattern of involvement), caregiving (i.e., parentified pattern of involvement), and cautious (i.e., apprehensive, vigilant, and guarded pattern of involvement) involvement. In demonstrating the developmental utility of parsing involvement, subsequent quantitative coding of these three forms of involvement was each associated with unique configurations of children's developmental outcomes 2 years later: (a) coercive involvement predicted externalizing problems, callousness, and extraversion, (b) caregiving involvement predicted separation anxiety, and (c) cautious involvement predicted separation anxiety and social withdrawal (Thompson, Davies, Hentges, et al., 2021). Toward identifying the underlying risk factors of each form of involvement, individual differences in children's history of experiences with interparental conflict emerged as a key precursor of subsequent changes in their involvement in conflicts 1 year later (Thompson, Davies, Coe, et al., 2021). However, there was considerable heterogeneity in links between interparental conflict antecedents and the three forms of children's involvement (Thompson, Davies, Coe, et al., 2021). Thus, the primary aim of this study was to examine children's affect-biased attention as a source of variability in links between interparental conflict and their subsequent involvement in interparental conflict.

Moderating role of affect-biased attention

Guided by developmental psychopathology models, pathways between family risk and children's subsequent coping and psychological difficulties are hypothesized to vary as a function of individual child attributes (e.g., temperament, age, sex; Davies & Sturge-Apple, 2014). Although there is a paucity of research that has examined the moderating role of children's affect-biased attention in models of interparental conflict, prevailing theories have proposed that children's attention biases to emotion-laden cues may alter children's reactivity to interparental conflict (Davies & Cummings, 1994; Grych & Fincham, 1990). Individual differences in affect-biased attention are regarded as early emerging forms of emotion regulation that alters children's responses to threat by selectively filtering children's tendency to attend to specific emotion-laden cues (Morales et al., 2016; Todd et al., 2012). Thus, although several studies have examined children's affect-biased attention as an outcome or mediator of socialization experiences, it may also reflect a predisposition for how children encode and process emotion-laden cues that modulate their vulnerability to threat and organize their behavioral responses to environmental stimuli (Burris et al., 2019; Öhman & Mineka, 2001; Todd et al., 2012). Our aim of examining children's affect-biased attention as a moderator of associations among interparental conflict and their forms of involvement are consistent with developmental psychopathology models and the premise that children's attributes can dynamically serve as both mediators and moderators across different developmental periods (Davies & Cicchetti, 2004; Davies & Martin, 2013).

Diathesis-stress models

Drawing on models examining children's susceptibility and vulnerability to environmental stimuli, the moderating effects of affect-biased attention may operate in two primary ways. First, the diathesis-stress model suggests that both the predictor and moderator operate as risk factors that increase children's vulnerability to developing psychological difficulties (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). More specifically, child attributes are proposed to potentiate children's vulnerability to high-risk contexts such that their adjustment problems are particularly pronounced when exposed to high levels of adversity (Monroe & Simons, 1991). Translated to the aims of the present study, the diathesis-stress model would be supported if: (a) interparental conflict and children's affect-biased attention are each risk factors for children's subsequent involvement in interparental conflict, and (b) links between interparental conflict and children's later involvement are exacerbated for children exhibiting greater affect-biased attention.

Although research has yet to examine children's affect-biased attention as a moderator of links between interparental conflict and distinct forms of children's involvement, the broader family risk literature provides some, albeit limited, support. Briggs-Gowan et al. (2015) found that children's attention to anger moderated concurrent links between exposure to family violence and their anxiety symptoms such that the link was stronger for children exhibiting heightened attention to anger. Consistent with the diathesis-stress model, attention to anger operated as a risk factor that exacerbated children's anxiety symptoms in the context of heightened family violence. Thus, one hypothesis would be that children's heightened attention to threatening stimuli may selectively sensitize children to subsequent environmental stressors and increase their vulnerability for coping and psychological difficulties only in specific socialization contexts (i.e., risky family contexts). Regarding the present study, this hypothesis would be supported if the pathway between interparental conflict and children's later involvement in interparental conflict is more pronounced for children displaying greater attention to negative emotions.

Contradicting this hypothesis, others have found that children's diminished attention to threat may operate as a vulnerability factor that amplifies links between risky family contexts and children's psychological difficulties (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2016). More specifically, family violence was marginally associated with children's subsequent trauma symptoms but only among children exhibiting greater attention away from anger. Thus, an alternative hypothesis is that children may selectively avoid threatening cues as one way to mitigate distress that as a result increases their risk for psychopathology specifically in risky family contexts. This hypothesis would be supported in the present study if the link between interparental conflict and children's subsequent involvement is amplified for children exhibiting diminished attention to negative emotion.

Differential susceptibility models

Further complicating an understanding of the moderating role of children's affect-biased attention, recent advances in deciphering the nature of interactions have revealed that previously characterized vulnerability factors may actually function as plasticity factors that increase children's susceptibility to both adverse and benign contexts (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). According to the differential susceptibility hypothesis, children's characteristics may increase their susceptibility to environmental conditions in a “for better and for worse” manner (Belsky & Pluess, 2009, 2016). Thus, although these plasticity factors are proposed to increase children's difficulties in the context of heightened stress, these factors are also associated with better developmental consequences in more benign or supportive contexts. Translated to the present study's aims, this hypothesis would be supported if children displaying relatively high levels of attention to negative emotions demonstrated higher risky involvement in the context of more destructive interparental conflict, but disproportionately lower risky involvement in the context of more benign or constructive interparental conflict. In contrast, children displaying lower attention to negative emotions relative to their peers would evidence a moderate level of risky involvement across the range of exposure to interparental conflict.

Supporting the role of affect-biased attention as a plasticity factor, Davies et al. (2020) found that children's attention to anger and fear moderated the prospective link between interparental conflict and their emotional insecurity in a for better and for worse fashion. Relative to children with diminished attention to angry and fearful faces, children exhibiting increased attention to angry and fearful faces evidenced both greater emotional insecurity in the context of heightened levels of interparental conflict and less emotional insecurity following exposure to minimal levels of interparental conflict. To our knowledge, however, this is the only study to more definitively evaluate the viability of children's affect-biased attention as a vulnerability factor or plasticity factor.

Although there is some support for examining children's affect-biased attention as a moderator of the pathway between interparental conflict and children's distinct forms of involvement, the limited, inconsistent findings do not provide sufficient bases for formulating definitive hypotheses on how affect-biased attention may operate as a moderator. Consistent with diathesis-stress models, one possibility is that heightened attention to threatening stimuli may amplify links between interparental conflict and children's later involvement in interparental conflict. An alternative possibility is that children may avoid threatening stimuli to mitigate distress and, accordingly, links between interparental conflict and forms of involvement would be stronger for children displaying diminished attention to threat. Still, another possibility is that children's threat-related attention bias operates as a plasticity factor rather than a diathesis. Thus, a third, alternative hypothesis is that children's affect-biased attention is associated with higher involvement in the context of destructive interparental conflict, but disproportionately lower involvement in the context of benign conflict. Because research examining the moderating role of children's affect-biased attention has yet to specifically examine affect-biased attention as a moderator of pathways between interparental conflict and children's distinct forms of involvement, these hypotheses are only speculative. Emphasizing the speculative nature of these hypotheses, previous studies examining the moderating role of affect-biased attention have yielded mixed findings on whether greater or diminished attention to negative emotions amplifies children's reactivity to family risk (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2015, 2016; Davies et al., 2020). Additionally, with the exception of a single study (Davies et al., 2020), research has not conducted systematic follow-up tests to determine whether children's affect-biased attention operates as a diathesis or a susceptibility factor in the context of family risk. To address this gap, the primary goal of this paper was to utilize more definitive analyses (e.g., proportion of interaction or PoI index) to directly examine whether the moderating role of children's affect-biased attention in the prospective link between interparental conflict and children's distinct forms of involvement corresponds more closely to differential susceptibility or diathesis-stress models (Del Giudice, 2017; Roisman et al., 2012).

Distinguishing between types of negative emotion

Findings from previous research suggest that distinguishing between different types of negative emotion may have important implications for understanding children's subsequent coping and psychological difficulties. For example, attention to anger and fear is more strongly associated with anxiety problems than attention to sadness. Likewise, attention to sadness has been shown to be selectively related to depression (see Mogg & Bradley, 2005 for a review). Differences in associations between attentional biases and psychopathology may be a result of selective adaptive functions of each specific emotion (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987). For instance, anger and fear are proposed to be more salient indicators of threat relative to other emotional stimuli (Öhman & Mineka, 2001; Öhman et al., 2001); however, whereas anger signals direct, immediate threat, fear signals the presence of danger but from an indirect source (Bannerman et al., 2009). In contrast to threat cues, sadness is proposed to signify hopelessness and loss (Hankin et al., 2010; Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987). Differences in the adaptive functions of different emotions may be particularly important for altering how children respond in aversive contexts. For instance, children who are pre-tuned to prioritize the processing of threat may be quicker to detect and to respond to potential danger than children who prioritize attention to sad emotional stimuli (Öhman & Mineka, 2001; Öhman et al., 2001). Although research has primarily examined attention to specific emotions at the risk factor level, the few studies examining the moderating role of children's attention biases provide some support for this premise. More specifically, these findings revealed that threat-related attention biases altered children's functioning in aversive contexts (e.g., exposure to interparental conflict, family violence), but sad attention biases did not (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2015, 2016; Davies et al., 2020). However, these findings must be interpreted carefully because only a single study on interparental conflict assessed attention biases to multiple negative emotions (Davies et al., 2020). To address this gap, the present study was designed to examine the moderating effects of children's attention to angry, fearful, and sad adult faces in the prospective link between interparental conflict and their distinct forms of involvement. However, due to the early stage of research in the area, we did not formulate any specific hypotheses regarding the role of children's attention to different negative emotions. Thus, the aims of this study are relatively exploratory in nature.

Developmental considerations

This study examined the moderating role of children's affect-biased attention in pathways among interparental conflict and three forms of their involvement in interparental conflict during children's transition from preschool-age to kindergarten for several developmental reasons. First, children's tendency to intervene in parental disputes is proposed to sharply increase around the preschool age (Davies & Cummings, 1994). Improvements in children's social perspective taking abilities during this developmental period may foster concerns about their parents' well-being and increase their risk of becoming involved in parents' conflicts (Cummings & Davies, 2010). Second, family characteristics have been identified as precursors of children's patterns of involvement in interparental conflict during kindergarten (Thompson, Davies, Coe, et al., 2021). Children's insecure coping strategies to risky family environments have demonstrated moderate stability during this developmental period and may provide templates for responding to extrafamilial stressors in ways that increase their risk for subsequent psychopathology (Macfie et al., 2015; Moss et al., 2005; Repetti et al., 2011). Lastly, greater variability in affect-biased attention has been demonstrated during this developmental period than during later developmental periods (e.g., adolescence; Jenness et al., 2021). This variability may reflect the emergence of meaningful individual differences in children's affect-biased attention, which may have significant implications for children's subsequent adjustment (Morales et al., 2016).

Present study

The present study provides the first test of the moderating role of children's attention to anger, fear, and sadness in the prospective link between interparental conflict and children's cautious, caregiving, and coercive involvement. To maximize the analytic rigor of our study, we utilized a comprehensive battery of assessments that incorporated a multi-method, multi-informant approach. More specifically, our assessment of interparental conflict included mother and partner report, trained coders' rating of maternal narratives, and trained coders' rating of an observational task. Additionally, we used a semi-structured interview assessment of involvement because: (a) the semi-structured interview assessment of involvement is currently the only psychometrically sound approach for measuring this specific taxonomy of involvement, and (b) interview approaches provide some additional advantages in assessing forms of involvement (Fiese & Spagnola, 2005; Thompson, Davies, Hentges, et al., 2021). More specifically, interview approaches capture parents' descriptions of children's characteristic responses across multiple interactions in the home; thus, reducing error or bias resulting from reliance on brief snapshots of behaviors in observational tasks and individual differences in parental interpretations of items and response alternatives on surveys (Fiese & Spagnola, 2005). Lastly, because eye tracking methodology offers several advantages over reaction time tasks (Burris et al., 2019; Gibb et al., 2016; Harrison & Gibb, 2015), we used eye tracking methodology to assess children's attention to angry, fearful, and sad adult faces during a visual search task designed to capture children's maintenance of attention following their initial identification of the negative emotional cues (Gibb et al., 2016). Further strengthening our analyses, we utilized a longitudinal design across two waves of data spaced 1-year apart and included Wave 1 autoregressive paths for forms of involvement to measure residualized change. We also specified child sex, household income, and parent education as covariates (Macfie et al., 2015).

METHOD

Participants

Two hundred and forty-three families (i.e., mother, intimate partner, child) were recruited from a moderate-sized metropolitan area in the Northeastern United States. We recruited families from multiple agencies (i.e., local preschools, Head Start agencies, public and private daycares) to obtain a diverse sample. At Wave 1, children were on average 4.6 years old (SD = .44) and about 56% of the children were female. The median household income among families was $36,000 per year (range = $2,000–$121,000) with most families (69%) receiving public assistance. Parents' median educational attainment was a general education diploma (GED) or high school diploma and about 19% of parents received less than a high school diploma or GED. Almost half of the families identified as Black or African American (48%), and the remaining families identified as White (43%), multi-racial (6%), or another race (3%). Approximately 16% of the family members identified as Latino. At Wave 1, the majority of parents were the child's biological parent (i.e., 99% of mothers and 74% of intimate partners). Almost half of partners (47%) were married and the majority of partners (93%) lived together currently. On average, the family triad interacted on a daily basis (range = daily to two or three days a week), and partners had lived together for an average of 3.36 years. The retention rate across the waves was 91%.

Procedures and measures

Families visited our research laboratory at two waves of data collection spaced 1 year apart. Data collection took place between 2010 and 2014. Research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Rochester prior to conducting the study (title: “Children's Development in the Family”; Approval #: 00030261). Families were compensated monetarily for participating.

Interparental conflict

Interparental conflict was assessed at Wave 1 using a multi-method, multi-informant approach, including coder ratings of maternal narratives, observational ratings, and mothers' and partners' survey reports. First, to obtain narrative assessments of interparental conflict, trained raters administered mothers the Interparental Disagreement Interview (IDI). The IDI is a well-established semi-structured, narrative interview designed to capture the frequency, course, and aftermath of common interparental disagreements (e.g., Davies et al., 2020). Mothers selected an interparental conflict topic that commonly occurs in front of the child and responded to a series of open-ended research questions pertaining to the nature of these conflicts (e.g., “How would you describe your disagreements over [topic]?” “How do you/your partner typically feel during these disagreements?”). Interviews were video recorded for later coding. Trained raters coded dimensions of interparental conflict along a continuum including both constructive and destructive forms of conflict for mothers and partners separately. More specifically, mothers' and partners' problem-solving, disengagement, aggression, and anger were rated along 7-point continuous scales (0 = none; 6 = high). Problem-solving indexed partners' constructive conflict tactics that were likely to be effective in managing and resolving disputes (e.g., demonstrated an empathetic understanding of their partners' perspective). Disengagement assessed partners' attempts to distance or disengage from the disagreement (e.g., partner expressed affective indifference pertaining to the conflict). Aggression indexed partners' verbal or physical hostility and aggression directed toward their partner (e.g., threats, insults, belittling statements). Anger reflected partners' signs of frustration, irritation, and fury (e.g., angry tone of voice, frustrated body language). Problem-solving was reverse scored so higher scores reflected minimal efforts among partners to resolve disputes and lower scores reflected partners' utilization of strategies to reduce or resolve conflicts. Interrater reliability was calculated based on intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of independent ratings on over 30% of interviews and ranged from .80 to .91 across codes. Narrative codes were aggregated to form a single manifest variable (α = .87).

Second, to capture observational assessments of interparental conflict partners participated in a 10-min interparental problem-solving task in which they discussed common, problematic disagreements in their relationship as they normally would at home (Gordis et al., 2001; Grych, 2002). While the child was in a separate room, experimenters instructed partners to select multiple problematic disagreement topics to discuss so they could move on to another topic if they finished discussing a previous topic. Partners could discuss any topic as long as they felt comfortable addressing it in front of their child. Children were then escorted to the room and introduced to a set of toys. Once the experimenter left the room, partners were instructed to begin their video-recorded conflictual discussion. To correspond with narrative ratings from the IDI, trained raters coded dimensions of interparental conflict that yielded comparable assessments of constructive and destructive forms of conflict. More specifically, coders rated the Comfort, Disengagement, Aggression, and Behavior Disorganization scales from the Interparental Conflict Expressions Coding System (e.g., Davies et al., 2020) and the Negative Escalation code from the System for Coding Interactions in Dyads (Malik & Lindahl, 2004). The Comfort, Disengagement, Aggression, and Behavioral Disorganization scales were rated separately for mothers and partners along 9-point molar scales (1 = not at all characteristic; 9 = highly characteristic). Comfort reflected the degree to which partners' expressed contentment, confidence, and satisfaction during disagreements (e.g., expressed relaxation during disagreements). Disengagement indexed partners' failure to devote energy, attention, or concern toward their partner during the disagreement (e.g., indifferent, unresponsive behavior, displays of helplessness and resignation). Aggression assessed partners' verbalizations and behavioral displays to psychologically or physically harm their partner (e.g., name-calling, threats, cruel remarks). Behavioral Disorganization was defined by partners' exhibiting affect expressions and conflict tactics that were volatile, unpredictable, and chaotic (e.g., loss of control, interaction asynchrony). Lastly, Negative Escalation was a dyadic couples conflict code rated along a 5-point molar scale that assessed partners' reciprocation or escalation of displays of anger, hostility, and negativity. Comfort was reverse scored so that higher scores reflected minimal signs of contentment or relaxation during the disagreement and lower scores reflected a higher degree of comfort. ICCs of independent ratings on 30% of interactions, ranged from .58 to .85 (M = .74) across the nine codes. Observational codes were aggregated to form a single manifest variable (α = .81).

Lastly, mothers and partners completed the Cooperation, Stonewalling, and Mild Physical Aggression scales for themselves and their partner from the Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales (Kerig, 1996) and mothers additionally completed the couples' Negative Escalation Scale from the Managing Affect and Disengagement Scale (Arellano & Markman, 1995). Cooperation captured the use of partners' reasoning, problem-solving, and cooperative efforts to resolve problems (16 items; e.g., “Listen to the other's point of view”). Stonewalling reflected an impasse between partners in ending their dispute (14 items; e.g., “Complain, bicker without really getting anywhere”). Mild Physical Aggression assessed partners' threatening or physical behavior that inflicted harm toward their partner (10 items; e.g., “Throw something”). Negative Escalation indexed partners' reciprocation of anger (six items; e.g., “Unable to get out of heated arguments”). Cooperation was reverse scored so that higher scores reflected partners' minimal use of constructive tactics to resolve disputes and lower scores reflected partners' greater use of constructive tactics. Internal consistencies for the four survey scales ranged from .80 to .92. Survey reports were aggregated to form a single manifest variable (α = .80).

We standardized and aggregated the narrative, observational, and survey manifest variables to form a single interparental conflict construct capturing the full continuum of constructive and destructive forms of conflict. The internal consistency of the composite was .71.

Children's affect-biased attention

Children's attention biases to angry, fearful, and sad facial stimuli were assessed at Wave 1 using a visual search task (Armstrong & Olatunji, 2012). As shown in Figure S1a, each trial began with a central fixation image (e.g., star) that was presented until the child was focused on the screen. Once the child was fixated on the fixation image, experimenters presented children with a circular matrix that simultaneously presented six faces of the same adult with five faces showing a neutral emotion and one target face showing either an angry, sad, or fearful expression. Each matrix was presented on the screen and was displayed for 3500 ms. This paradigm contains both a visual search and a passive viewing component (illustrated in Figure S1b). Reflecting the visual search aspect of the paradigm, children were instructed to always watch the screen and find the face that was different from the others with their eyes and without pointing or talking. Accordingly, upon the presentation of each matrix, children's primary goal was to find the target face. To capture the passive viewing component, experimenters deliberately refrained from instructing children on what to do after finding the target emotion face. Thus, after finding the target face, children could freely attend to any of the 6 faces for the remainder of the matrix presentation. This unstructured aspect of the task captured individual differences in children's allocation of their attention to the target face.

Emotional stimuli included color photographs of adult male and female actors varying in race (i.e., Black or White) and were derived from the NimStim Face Stimulus Set (Tottenham et al., 2009). Adult faces were displayed in an 8.6 × 6.7 cm height to width format and configured in a circle with 0.10 cm between each image horizontally and 0.5 cm vertically. The task included five practice trials and 24 target trials. Each type of negative emotion (i.e., anger, sadness, fear) was displayed eight times. Negative emotions were displayed in a randomly generated order and the position of the target face in the matrix varied randomly.

Tobii Studios software was used to develop and administer the visual search paradigm and a 17-inch TFT Tobii T60 eye-tracking monitor (60 Hz data rate, 1280 × 1024 pixels) displayed emotional stimuli and recorded eye movements. The Tobii infrared eye tracker tracks the center of the pupil and the corneal surface reflection to assess the position of gaze. Prior to the start of the task, children completed a five-point calibration procedure that consisted of tracking specific points across the center of the screen to the corners of the monitor. Gaze data are accurate to 0.5° with an error (drift) of 0.1°. Children sat approximately 60 cm from the monitor during the task. For each trial, attention was measured using predefined areas of interest (AOIs) that consisted of the entire contour of each of the six adult faces in the matrix. Fixations were defined as gaze positions that were stable within a 1° visual field for a span of at least 100 ms within an AOI. We used the Tobii Fixation filter to identify fixations based on a velocity threshold of 0.42 pixels/ms.

Because of its established use in the literature as a measure of attention bias, we calculated duration of attention to assess children's attention to negative emotion stimuli during the visual search task (Guastella et al., 2009). Duration of attention to faces was calculated separately for angry, sad, and fearful conditions. Individual differences in duration of attending to negative emotions may reflect variations in task engagement or preferences to attend to non-social stimuli (e.g., avoiding faces in the task). Thus, to assess children's selective attention to angry, sad, and fearful faces relative to neutral faces, the attention duration measure for each negative emotion was calculated as the average length of participant fixation to the target AOI (i.e., negative face) divided by the sum of the average length of fixation for all the faces (i.e., target face + five neutral faces). Although children's attention to negative emotions was calculated using both the visual search and passive viewing components of the paradigm, children's duration of attention to negative emotions was only computed if they initially detected the target face. Thus, trials were only included in the calculation of proportions if children fixated on the AOI with the negative emotion. Data were considered missing in the calculation of variables if children did not fixate on at least 5 of 8. (i.e., 63%) of the trials within each emotion condition (missing data ranged from 27% to 34% across emotion conditions).

Children's involvement in interparental conflict

Children's involvement was assessed using the IDI at Waves 1 and 2. In addition to assessing the nature and course of common problematic disagreements, the IDI captures children's behavioral and emotional reactivity during and immediately following parental disputes. Mothers responded to a series of open-ended questions pertaining to children's behavioral (e.g., “During these disagreements that [child] sees or hears, how does s/he respond?”) and emotional (e.g., “How do you think [child] feels during these disagreements?”) reactivity in response to the interparental conflict. Interviews were recorded for later coding. The three forms of involvement were identified through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2012; Thompson, Davies, Hentges, et al., 2021). Trained raters coded each form of children's involvement from the IDI along 5-point molar scales (1 = not at all characteristic; 5 = highly characteristic). We supplemented molar ratings with presence (1) and absence (0) tallying of nine behaviors across the IDI.

Coercive involvement

Molar ratings indexed children's physical or verbal attempts to interrupt or end parental disputes by undermining parental authority (e.g., talking over parents, misbehaving). Presence and absence tallying included children's (a) anger, frustration, irritation, or fury expressed through facial, postural or gestural, or verbal expressions; (b) aggression, verbal or physical hostility; and (c) authoritarian behavior, behaviors that undermined parental authority through the use of power and coercion.

Caregiving involvement

Molar assessments were characterized by children's provision of instrumental or emotional support to one or both parents (e.g., comforting parents, acting as a confidante). Presence and absence tallying included children's (a) comfort, providing verbal or physical support to one or both parents; (b) sadness, overt expressions of feeling down or dejected through facial, postural or gestural, or verbal expressions; and (c) problem-solving, active involvement in generating solutions to interparental problems.

Cautious involvement

Molar ratings reflected children's reticent and guarded involvement in interparental conflict characterized by their heightened awareness of danger and threat accompanying interparental interactions (e.g., slowly approaching parents, hiding behind a parent). Presence and absence tallying included children's (a) vigilance, being watchful or on high alert; (b) self-protection, attempts to preserve their safety; and (c) distress, signs of anxiety, fear, or worry.

Three trained raters independently coded 100% of the interviews at Waves 1 and 2. ICCs for molar ratings of involvement ranged from .74 to .89 at Wave 1 and .80 to .89 at Wave 2. Presence and absence tallies were summed (range = 0–3) and ICCs ranged from .86 to .91 at Wave 1, and from .88 to .92 at Wave 2. We standardized and aggregated molar ratings and tallies to form single indices of children's coercive, caregiving, and cautious involvement. Cronbach's alphas ranged from .84 to .92 at Wave 1 and from .71. to .92 at Wave 2.

Covariates

Three covariates were extracted from the maternal demographic interview: (a) child sex (0 = female, 1 = male), (b) total household income, and (c) parent education, ranging from 1 (7th grade or less) to 7 (graduate degree).

RESULTS

Table S1 includes the means, standard deviations, and correlations of primary study variables. Prior to conducting the primary analyses, we examined the data to determine whether any of the primary study variables were associated with rates of missingness. Eight of 16 variables were associated with rates of missingness. More specifically, higher rates of missingness were associated with lower household income at Wave 1 (r = .21, p = .001), lower parent education at Wave 1 (r = −.21, p = .001), higher levels of destructive interparental conflict at Wave 1 (r = .18, p = .01), diminished attention to fearful faces at Wave 1 (r = −.18, p = .02), diminished attention to sad faces at Wave 1 (r = −.22, p = .01), higher levels of caregiving (r = .22, p = .001) and coercive (r = .14, p = .03) involvement at Wave 1, and higher levels of caregiving involvement at Wave 2 (r = .13, p = .05). Because full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods provide accurate parameter estimates for all types of missing data when the amount of missing data is less than 20% (Schlomer et al., 2010), we used FIML to retain the full sample of families given that data in our sample were missing for 13% of values. Primary analyses were conducted using AMOS 27.0 software (Arbuckle, 2020).

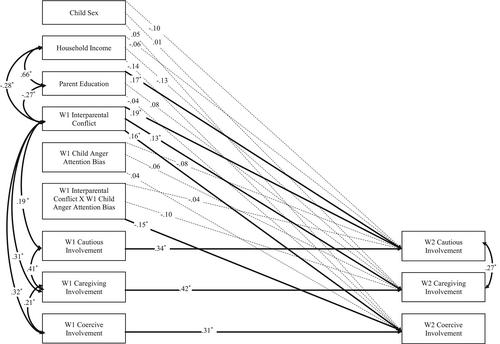

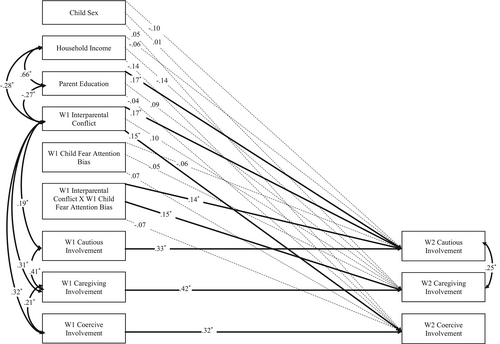

To examine the moderating effect of children's attention biases, we mean-centered composites of interparental conflict and children's attention bias to the target emotion to reduce problems associated with multicollinearity. We specified interparental conflict, children's attention bias to the target emotion, and their multiplicative interaction as simultaneous predictors of children's Wave 2 cautious, caregiving, and coercive involvement. Because multiplying each attention bias factor with the same predictor substantially increases collinearity among interaction terms, we estimated three consecutive path models to reduce analytic complexity of models by examining each of the three attentional biases (i.e., anger, fear, sadness) in three separate models. To increase methodological rigor, we estimated autoregressive paths between children's Wave 1 and Wave 2 forms of involvement. Additionally, we specified correlations (a) between all exogenous variables and (b) between the residual errors of forms of involvement. For clarity, only significant correlations are depicted in Figures 1 and 3. The resulting models provided a good fit with the data: (1) anger bias, χ2(6) = 3.56, p = .74, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .00, comparative fit index [CFI] = 1.00, and χ2/df ratio = .59; (2) fear bias, χ2(6) = 3.11, p = .80, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00, and χ2/df ratio = .52; and (3) sad bias, χ2(6) = 4.01, p = .68, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00, and χ2/df ratio = .67.

Model 1: Children's attention bias to anger

Model findings for the moderating effect of children's attention bias to angry faces are depicted in Figure 1. Autoregressive paths for each cautious, β = .34, p < .001, caregiving, β = .42, p < .001, and coercive, β = .31, p < .001, involvement were significant. Greater parent educational attainment was significantly associated with higher levels of children's cautious involvement at Wave 2, β = .17, p = .04. Examination of main effects revealed that interparental conflict predicted children's cautious, β = .19, p = .004, caregiving, β = .13, p = .05, and coercive, β = .16, p = .02, involvement at Wave 2. However, children's attention bias to angry faces was not associated with forms of involvement at Wave 2 (p > .26). Children's attention bias to anger moderated the association between interparental conflict and children's Wave 2 coercive involvement, β = −.15, p = .04, but not children's Wave 2 caregiving, β = −.10, p = .18, or cautious, β = −.04, p = .60, involvement. The interaction for coercive involvement did not survive Bonferroni corrections.

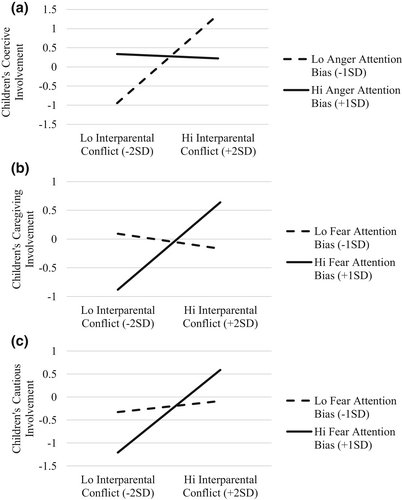

To further understand the form of the interaction, we calculated the graphical plot and simple slope analyses of the interaction from the parameter estimates of the full path model in Figure 1. In accord with statistical recommendations for visually depicting interactions (Del Giudice, 2017; Roisman et al., 2012), we computed the graphical plot at ±2 SD of the mean of interparental conflict and ±1 SD of the mean of children's attention bias to anger as depicted in Figure 2. Simple slope analyses revealed that the association between interparental conflict and children's Wave 2 coercive involvement was significant for children with diminished attention to anger, b = .60, p = .004, but not for children with higher levels of attention to anger, b = −.03, p = .87. More specifically, diminished attention to anger was associated with greater coerciveness at higher levels of interparental conflict, but with lower coerciveness in the context of benign conflict. Although the nature of the interaction is visually consistent with differential susceptibility, we also calculated the PoI index. The PoI provides the most definitive test of the form of moderation and indexes the ratio of area of the interaction where children with diminished attention bias to anger exhibit fewer coercive involvement behaviors than children with high attention bias to anger relative to the overall aggregate of their for better and for worse functioning (Roisman et al., 2012). Whereas PoI values falling below .20 support dual risk models, values falling between .20 and .80 support differential susceptibility (Del Giudice, 2017). Confirming visual inspection of the plot, the resulting PoI value of .55 is consistent with differential susceptibility models.

Model 2: Children's attention bias to fear

Results for the moderating effect of children's attention bias to fearful faces are depicted in Figure 3. In accord with model findings in Figure 1, autoregressive paths for each cautious, β = .33, p < .001, caregiving, β = .42, p < .001, and coercive, β = .32, p < .001, involvement were significant. Greater parent educational attainment was significantly associated with higher levels of children's cautious involvement at Wave 2, β = .17, p = .03. Examination of main effects revealed that interparental conflict predicted children's cautious, β = .17, p = .01, and coercive, β = .15, p = .03, involvement at Wave 2, but not their Wave 2 caregiving involvement, β = .10, p = .11. Children's attention bias to fearful faces was not associated with forms of involvement at Wave 2 (p > .33). However, children's attention bias to fear moderated the association between interparental conflict and children's Wave 2 cautious, β = .14, p = .05, and caregiving, β = .15, p = .02, involvement, but not children's Wave 2 coercive involvement, β = −.07, p = .34. The interactions for cautious and caregiving involvement did not survive Bonferroni corrections.

In characterizing the interaction between children's attention to fear and interparental conflict to predict children's Wave 2 caregiving and cautious involvement, we calculated the graphical plot and simple slope analyses of the interaction from the parameter estimates of the full path model in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 2b,c, we computed the graphical plot at ±2 SD of the mean of interparental conflict and ±1 SD of the mean of children's attention bias to fear. Whereas the association between interparental conflict and children's Wave 2 caregiving involvement was significant for children with high levels of attention to fear, b = .41, p = .01, the association was not significant for children with low levels of attention to fear, b = −.07, p = .65 (see Figure 2b). Visual inspection of the plot revealed an interaction pattern consistent with differential susceptibility; however, we also calculated the PoI which had a value of .59, thus confirming visual consistency with differential susceptibility. Likewise, the association between interparental conflict and children's Wave 2 cautious involvement was also significant for children with high levels of attention to fear, b = .48, p = .001, but the association was not significant for children with low levels of attention to fear, b = .07, p = .67 (see Figure 2c). Visual inspection of the plot and a PoI value of .62 provide support for differential susceptibility.

Model 3: Children's attention bias to sadness

Consistent with results from Models 1 and 2, autoregressive paths for each cautious, β = .35, p < .001, caregiving, β = .42, p < .001, and coercive, β = .33, p < .001, involvement were significant. Greater parent educational attainment was significantly associated with higher levels of children's cautious involvement at Wave 2, β = .16, p = .04. Additionally, lower household income was significantly associated with children's Wave 2 caregiving involvement, β = −.16, p = .05. Examination of main effects revealed that interparental conflict predicted children's Wave 2 cautious involvement, β = .18, p = .01, but not children's caregiving, β = .10, p = .12, or coercive, β = .13, p = .05, involvement at Wave 2. Children's attention bias to sad faces was not associated with forms of involvement at Wave 2 (p > .24). Furthermore, children's attention bias to sad faces did not moderate the association between interparental conflict and children's Wave 2 cautious, caregiving, or coercive involvement (p > .21). Structural path coefficients are depicted in Figure S2.

Follow-up analysis: Children's attention to general negative emotions

We conducted a follow-up analysis to determine whether distinguishing between types of negative emotions provides a more precise understanding of the associations between different negative emotions and children's distinct forms of involvement in comparison to children's attention to general negative emotions. By aggregating children's attention to angry, sad, and fearful faces into a composite of general negative emotion, children's general attention to negative emotions only moderated the association between interparental conflict and their coercive involvement (see Figure S3 for details). Our follow-up analysis suggests that examining the moderating role of different types of negative emotion separately provides a more comprehensive account of the precise moderating effects of children's attention to negative emotions in associations among interparental conflict and children's distinct forms of involvement.

DISCUSSION

Previous research has found that interparental conflict is a significant precursor to children's cautious, caregiving, and coercive involvement; however, there is considerable heterogeneity in links between interparental conflict and children's distinct forms of involvement (Thompson, Davies, Coe, et al., 2021). Theoretical and empirical work suggest that pathways between interparental conflict and children's functioning may vary as a function of their affect-biased attention (Davies & Cummings, 1994; Davies et al., 2020; Grych & Fincham, 1990). However, research has yet to examine whether children's affect-biased attention alters the prospective link between interparental conflict and their distinct forms of involvement. To address this gap, we utilized a multi-method, multi-informant, longitudinal design to examine whether children's attention bias to angry, fearful, and sad adult faces moderated associations between interparental conflict and their cautious, caregiving, and coercive involvement 1 year later. Moderator analyses demonstrated that the link between interparental conflict and children's subsequent coercive involvement was amplified when children's attention to anger was low. In addition, the moderator findings revealed that pathways between interparental conflict and children's cautious and caregiving involvement 1 year later were magnified when children's attention to fear was high. In contrast, sad attention biases did not emerge as a significant moderator. Because sadness is more indicative of loss and hopelessness (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987), it may be particularly salient in the development of specific forms of psychopathology (e.g., depression) rather than in mobilizing responses to threat in risky family contexts (Harrison & Gibb, 2015). Moderation findings were consistent with differential susceptibility models revealing that children's affect-biased attention operated as a plasticity factor associated with children's susceptibility to interparental conflict in a “for better and for worse” manner. Children displaying an attention bias exhibited disproportionately greater involvement following their exposure to heightened levels of interparental conflict, but less involvement following exposure to benign interparental conflict.

More specifically, moderation analyses revealed that children's attention to fear was associated with higher levels of cautious and caregiving involvement following their exposure to destructive interparental conflict, and lower levels of cautious and caregiving involvement following their experiences with benign interparental conflict. Our findings are consistent with previous research, which found that children with higher attention to fear moderated the association between interparental conflict and children's emotional insecurity in a for better and for worse fashion relative to children with decreased attention to fear (Davies et al., 2020). Research on emotion processing and understanding during early childhood suggests that children have the most difficulty recognizing and understanding fearful expressions (Camras & Allison, 1985). Thus, one possibility is that children's heightened attention to fear reflects higher engagement in processing and understanding more complex emotion-laden contexts. According to environmental sensitivity frameworks, children's deeper and more thorough information processing and greater attentional processing of environmental cues may heighten their sensitivity to the environment in a for better and for worse manner (Aron et al., 2012; Greven et al., 2019). Moreover, children's processing of fearful expressions may be particularly salient as a plasticity factor in modulating their cautious and caregiving involvement in the context of interparental conflict. First, in threatening contexts, greater processing of fearful faces may foster children's inhibited behavior reflecting a “pause to check” strategy that allows for deeper processing of fearful expressions that functions to gather information about the source of threat and to weigh the costs and benefits of approaching or avoiding threat (Aron et al., 2012). Translated to the context of interparental conflict, this may manifest in children's cautious, reticent, and guarded forms of involvement reflecting their simultaneous impulses to engage and avoid parental disputes. The processing of fearful expressions has also been proposed to activate the caregiving system and to be critical in the development of empathic responses (Frick et al., 2014; Grusec & Davidov, 2010; Hilburn-Cobb, 2004). Research further suggests that sensory processing sensitivity is associated with activity in brain regions involved in empathy (Acevedo et al., 2018). Accordingly, in risky family contexts, children's observation of fearful expressions may precociously activate their caregiving system and foster their concerns about the welfare of their family. Adapted to the context of interparental conflict, children's heightened attention to fearful faces may engender their parentified patterns of involvement reflecting their concerns regarding parental distress and escalating family tension.

Second, if children's heightened attention to fearful faces is associated with better emotion understanding skills because of higher engagement with complex emotions, then it is possible that children may more easily recognize and capitalize on their tendencies to process affective cues in more benign or supportive contexts (Aron et al., 2012). Through a combination of children's already advanced emotion understanding and their utilization of environmental supports, children may develop superior social problem-solving skills that, in turn, facilitate better psychological functioning. Thus, in the context of benign interparental conflict, children's heightened processing of complex emotions may facilitate their quicker processing of parents' subtle displays of comfort and support. Parental signs of comfort and support, in turn, are theorized to increase children's confidence in parents' ability to resolve conflicts reducing children's emotional insecurity and enhancing their well-being by teaching effective emotion regulation and social problem-solving skills (Zemp et al., 2014). Consequently, children may exhibit fewer risky involvement behaviors in the context of benign interparental conflict.

Our findings further revealed that the association between interparental conflict and children's coercive involvement was stronger for children displaying diminished attention to anger. Although our study is the first to examine the interplay between interparental conflict and attention to anger in predicting children's involvement in interparental conflict, our findings are broadly consistent with previous research findings indicating that the association between children's abuse experiences and their trauma symptoms were significantly stronger for children who exhibited diminished attention to anger (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2016). Although the authors interpreted this finding as support for the role of diminished attention as a diathesis (or dual risk) that potentiated the risk conferred by abuse, they did not conduct follow-up analyses (e.g., PoI) to definitively identify if moderation was expressed in a diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility manner. Consistent with differential susceptibility, follow-up PoI and simple slope analyses in the present study found that children exhibiting diminished attention to anger displayed higher levels of coercive involvement following exposure to destructive conflict, but lower levels of coercive involvement following benign conflict.

Conceptual models may offer explanations as to why diminished attention to anger may be a plasticity factor. Theory and research suggest that children's diminished attention to negative emotions may reflect an adaptive process that facilitates their effective regulation of any feelings of vulnerability in favor of more bold, aggressive, and domineering behaviors (Bretherton & Munholland, 1999; Thompson, 2008). Because anger is a sign of direct, imminent threat (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987), children's avoidance of angry expressions may be particularly salient in reducing their distress and engendering responses designed to defeat and overcome threat. Accordingly, emotional security theory proposes that children's downplaying of attention toward negative emotions is a key component of their generation of dominant reactivity patterns characterized by their anger, vigilance, defensiveness, and suppression of vulnerable negative emotions in the context of destructive interparental conflict (Davies & Martin, 2013). Thus, toward understanding children's functioning in the “for worse” side of the interaction, children's diminished attention to anger in the context of hostile, unresolved conflict may function to minimize vulnerability and selectively engender their coercive and domineering ways of intervening in interparental disputes. In contrast to destructive levels of interparental conflict, benign levels of interparental conflict are proposed to present as a milder, manageable source of interpersonal threat that may foster children's secure and well-regulated responses to conflict (Davies & Martin, 2013). If diminished attention to anger helps regulate children's vulnerability, then in the context of benign conflict, children's avoidance of anger may enable them to effectively manage distress while maintaining sustained attention to social and exploratory opportunities that facilitate more constructive, self-confident responses to threat (Davies & Martin, 2013). Thus, turning to children's functioning in the “for better” side of the interaction, children's relatively low levels of attention to anger in the context of benign conflict may be associated with lower tendencies to exhibit coercive responses.

Although this is the first study to examine children's affect-biased attention as one source of variability in the pathway between interparental conflict and children's distinct forms of involvement, it is important to consider avenues for future research. First, our findings revealed that attention bias to fear moderated interparental conflict in a similar manner for cautious and caregiving involvement. Previous research though provides evidence that not only suggests that the forms of involvement are distinct but also that different dimensions of interparental conflict (i.e., disengaged, hostile, constructive) may be differentially associated with each form of involvement (Thompson, Davies, Coe, et al., 2021). Thus, building on this research, future analyses may reveal that children's preferential attention to specific emotions may confer selective susceptibility for specific forms of interparental conflict and their involvement. For instance, attention to threat-related cues in the context of hostile forms of conflict may be particularly salient in engendering children's hypervigilant, reticent, and guarded involvement strategies. In contrast, in the context of disengaged forms of conflict, attention to threat-related cues may be critical in activating children's caregiving system to preserve family relationships. Second, due to model complexity and sample size, we examined the moderating effect of children's attention bias to angry, fearful, and sad faces across three consecutive models. Although this decision was consistent with previous research (e.g., Briggs-Gowan et al., 2015, 2016; Davies et al., 2020), a critical next step will be to further distinguish between these emotions and their incremental function as moderators.

Findings must also be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, although multiple studies have found that happy attention biases do not moderate contexts of family risk (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2015; Davies et al., 2020), this study focused only on the role of attention to negative emotions (i.e., sadness, anger, fear). Thus, it is unclear how attention to positive emotions may operate as a moderator in links between interparental conflict and children's involvement. Second, we utilized an established approach to assessing affect-biased attention (e.g., Davies et al., 2020); however, there may also be other useful alternative methods for assessing these biases. For instance, expansions to the visual search task may benefit from capturing children's biased attention toward neutral faces by including neutral faces as the target face and negative emotions as the distractors. Third, although the semi-structured interview assessment is the only available and psychometrically sound approach for capturing children's cautious, caregiving, and coercive involvement, expanding measurement batteries to include other methods is an important direction for future research. Third, rates of missing data for the visual search task ranged 27%–34%. It is possible that rates of missing data reduced some analytic power. Fourth, although the lower range of ICCs fell below acceptable (i.e., interrater reliability for the observational assessment of partners' Behavior Disorganization and Comfort fell below .70), it is not uncommon for higher-order composites to demonstrate good reliability when ICCs fall in the .50 range (e.g., Sohr-Preston et al., 2013). Lastly, the sample reflects a relatively diverse sample in terms of race and socioeconomic status. However, future research with other samples (e.g., clinical) will be necessary to examine the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, previous research has demonstrated that interparental conflict is an important risk factor for children's cautious, caregiving, and coercive involvement. However, in addressing the documented heterogeneity of this risk, our study provides the first test of the moderating role of children's affect-biased attention in the prospective link between interparental conflict and these three forms of children's involvement. Consistent with differential susceptibility, children's affect-biased attention operated as a plasticity factor in the context of interparental conflict; however, the direction of children's attention was selective based on the type of negative emotion. More specifically, whereas the link between interparental conflict and children's coercive involvement 1 year later was stronger for children exhibiting low attention to anger, pathways between interparental conflict and children's subsequent cautious and caregiving involvement were amplified among children displaying high attention to fear. At a translational level, children experiencing high levels of interparental conflict and exhibiting affect-biased attention displayed the greatest levels of involvement in interparental conflict. Because forms of children's involvement have been linked primarily with subsequent psychopathology (Thompson, Davies, Hentges, et al., 2021), these children may benefit the most from early intervention and prevention programs that may disrupt the cascade of processes increasing children's risk for maladjustment. For instance, because children exhibiting the lowest vulnerability to risky involvement were exposed to benign or even constructive interparental conflict, interventions designed to teach parents problem-solving and communication skills may support children's positive development (e.g., Goodman et al., 2004). Alternatively, there is growing support for attention bias modification training in reducing children's psychopathology symptoms (e.g., Chang et al., 2019); thus, with further research, it is possible that attention bias modification training may be utilized to retrain children's risky coping responses specifically in the context of destructive interparental conflict.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted at the Mt. Hope Family Center and supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD065425) awarded to Patrick T. Davies and Melissa L. Sturge-Apple. We also thank Mike Ripple and the Mt. Hope Family Center Staff and the families who participated in the research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data and materials necessary to reproduce the analyses presented here are publicly accessible. Data and materials are available at the following URL: https://osf.io/ejfup/. The analytic code necessary to reproduce the analyses presented in this paper is not publicly accessible. The analyses presented here were not preregistered.