South American haemorrhagic fevers are viral infections that may result in haemorrhage and organ malfunction, which often leads to death. A history of travel or work in endemic regions in South America, contact with rodents or their excreta, and development of haemorrhagic symptoms are key to diagnosis.

Often presents with non-specific influenza-like or dengue-like symptoms in the first week of illness; around 20% to 30% go on to develop haemorrhagic or neurological symptoms in the second week, which often results in multi-organ failure and death.

Healthcare workers should use full personal protective equipment and ensure laboratory samples are appropriately labelled and transported.

Diagnosis is confirmed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Treatment for all symptomatic patients is supportive care.

South American haemorrhagic fevers (SAHFs) are viral infections that may result in haemorrhage and organ malfunction, which often leads to death.[1]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs): about viral hemorrhagic fevers. Apr 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/viral-hemorrhagic-fevers/about/index.html

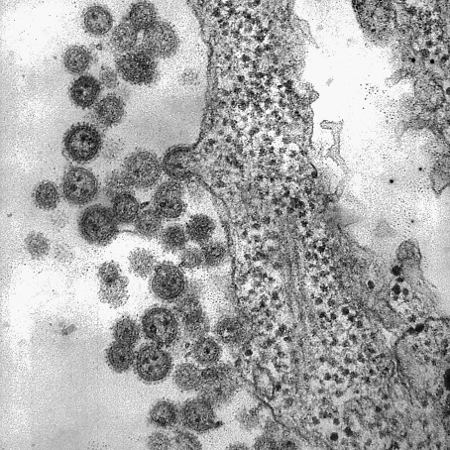

The viral infections are caused by clade B New World arenaviruses (family Arenaviridae; genus Mammarenavirus) that naturally infect rodents, but can be passed to humans mainly through aerosolisation and mucous membrane contact with infected rodent secretions and excreta. While uncommon, these viruses can be transmitted between humans through contact with infected bodily fluids (e.g., saliva, urine, faeces, blood). Nosocomial and laboratory spread have also been described.[2]Patterson M, Grant A, Paessler S. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;5:82-90.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4028408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636947?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Gómez RM, Jaquenod de Giusti C, Sanchez Vallduvi MM, et al. Junín virus. A XXI century update. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:303-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21238601?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Enria DA, Briggiler AM, Sánchez Z. Treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 2008;78:132-9.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10245337

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18054395?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]Enria DA, Briggiler AM, Feuillade MR. An overview of the epidemiological, ecological and preventive hallmarks of Argentine haemorrhagic fever (Junin virus). Bulletin Institut Pasteur. 1998;96:103-114.[6]de Manzione N, Salas RA, Paredes H, et al. Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever: clinical and epidemiological studies of 165 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:308-13.

http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/26/2/308.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9502447?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National notifiable diseases surveillance system (NNDSS). Viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) 2025 case definition. 2024 [internet publication].

https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/viral-hemorrhagic-fever-vhf

SAHFs occur in Bolivia, Argentina, Venezuela, and Brazil. Different viruses are responsible for causing disease in these countries; for example, Chapare and Machupo viruses in Bolivia, Guanarito virus in Venezuela, Junin virus in Argentina, and Sabia virus in Brazil.[2]Patterson M, Grant A, Paessler S. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;5:82-90.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4028408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636947?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Gómez RM, Jaquenod de Giusti C, Sanchez Vallduvi MM, et al. Junín virus. A XXI century update. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:303-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21238601?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Enria DA, Briggiler AM, Sánchez Z. Treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 2008;78:132-9.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10245337

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18054395?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]Enria DA, Briggiler AM, Feuillade MR. An overview of the epidemiological, ecological and preventive hallmarks of Argentine haemorrhagic fever (Junin virus). Bulletin Institut Pasteur. 1998;96:103-114.[6]de Manzione N, Salas RA, Paredes H, et al. Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever: clinical and epidemiological studies of 165 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:308-13.

http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/26/2/308.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9502447?tool=bestpractice.com

[8]Delgado S, Erickson BR, Agudo R, et al. Chapare virus, a newly discovered arenavirus isolated from a fatal hemorrhagic fever case in Bolivia. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000047.

http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1000047

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18421377?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Barry M, Russi M, Armstrong L, et al. Brief report: treatment of a laboratory-acquired Sabiá virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:294-296.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199508033330505

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7596373?tool=bestpractice.com

This is due to the presence of different rodent vectors in each country.

Other New World arenaviruses that have been reported to cause clinical disease in humans include Flexal virus (Brazil) and Tacaribe virus (Trinidad and Tobago); however, they are not regarded as viral haemorrhagic fever viruses. Furthermore, very few cases have been reported, and all have resulted from laboratory exposure.[10]Sarute N, Ross SR. New world arenavirus biology. Annu Rev Virol. 2017 Sep 29;4(1):141-58.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7478856

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28645238?tool=bestpractice.com

BMJ talk medicine podcast: South American haemorrhagic fevers, with Prof Thomas Ksiazek

Opens in new window

Log in or subscribe to access all of BMJ Best Practice