Recommendations

Key Recommendations

During periods of high COVID-19 prevalence, for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia with symptoms and signs that start at any point after hospital admission, see Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Consider all patients with cough, fever, or other suggestive symptoms to have COVID-19 until proven otherwise. Pneumonia due to COVID-19 is not covered in this topic.

For patients with symptoms and signs consistent with bacterial pneumonia (not secondary to COVID-19) that start on days 1 or 2 after hospital admission, see Community-acquired pneumonia (non COVID-19).

Diagnosis of HAP requires a combination of abnormal imaging plus 2 of 3 clinical features: fever >100.4°F (>38°C), leukocytosis or leukopenia, or purulent secretions.[1] Other symptoms could include cough, chest pain, or malaise. Physical exam signs may include asymmetric expansion of the chest, diminished resonance, abnormal auscultation of the lung (egophony, whisper pectoriloquy, crackles, or rhonchi), or tachycardia. Immunocompromised patients may lack typical clinical signs. Proposed diagnostic criteria for immunocompromised host pneumonia include the clinical suspicion of a lung infection, with or without compatible clinical signs and symptoms, and with radiographic evidence of a new or worsening pulmonary infiltrate.[54]

Information gained from imaging, a thoracentesis, oxygenation, and a Gram stain should be optimized.

It is good to have a high suspicion for HAP/ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) because mortality is lower when the correct treatment is started sooner. Clinical criteria alone, without the aid of C-reactive protein or the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score, should be used to determine whether to start antimicrobial therapy for HAP or VAP.[1]

History and physical exam

The history should ascertain whether the patient is at risk of pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and MRSA). This is important to establish, as it affects empiric antibiotic options. The risk factors for MDR pneumonia are:

Antimicrobial therapy in the preceding 90 days

Septic shock at the time of VAP

Acute respiratory distress syndrome preceding VAP

Current admission to the hospital of 5 or more days

Acute renal replacement therapy prior to VAP onset.

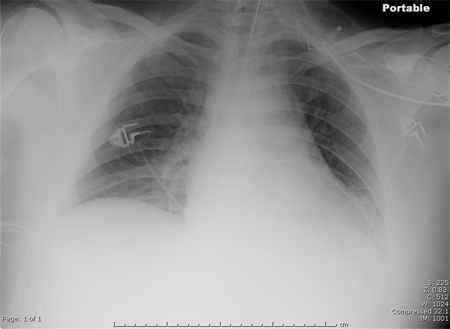

Chest imaging and diagnostic thoracentesis

Chest imaging showing opacity, whether focal or diffuse, is required for diagnosis. Chest x-rays are typically performed for all patients, whether on a hospital floor or in the ICU. A posterior-anterior film with a lateral view is preferred. A computed tomography (CT) scan may be necessary, especially if the radiograph is of poor quality or an ill-defined opacity is present. Ultrasound may be considered.[55] The American College of Physicians recommends point-of-care ultrasound if there is diagnostic uncertainty in patients with acute dyspnea.[56]

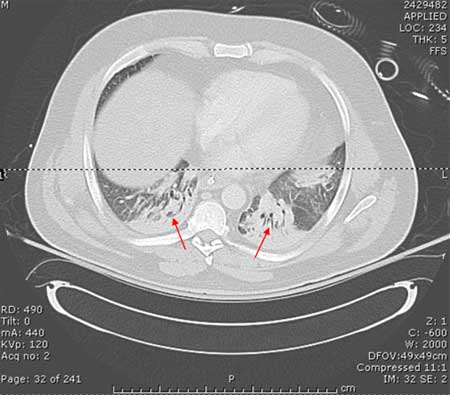

If pleural fluid is seen on chest x-ray and the amount is considered to be more than minimal, a diagnostic thoracentesis should be performed. Tests from pleural fluid that indicate that the pleural space needs to be drained are a pH <7.20, a glucose level <40 mg/dL, and an LDH level >1000 U/L.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Portable chest x-ray of a patient with HAP. Note obscured left hemidiaphragm due to a left lower lobe opacity and an obscured heart border due to a left upper lobe or lingular opacityConsent obtained at University of Louisville, KY [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing bibasilar opacities of patient with HAPConsent obtained at University of Louisville, KY [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing bibasilar opacities of patient with HAPConsent obtained at University of Louisville, KY [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of a patient with a large, dense left lower lobe infiltrateConsent obtained at University of Louisville, KY [Citation ends].

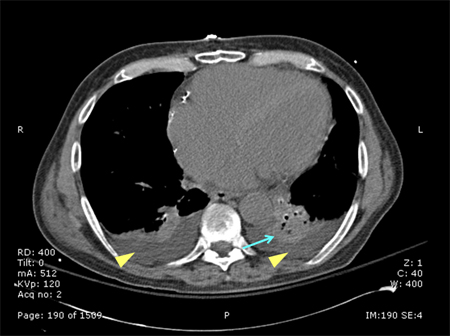

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of a patient with a large, dense left lower lobe infiltrateConsent obtained at University of Louisville, KY [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of a patient with a left lower lobe alveolar infiltrate (blue arrow), bilateral pleural effusions (yellow arrowheads), and right basilar atelectasis; notice the line separating the two shades of gray representing the infiltrate and the fluidConsent obtained at University of Louisville, KY [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of a patient with a left lower lobe alveolar infiltrate (blue arrow), bilateral pleural effusions (yellow arrowheads), and right basilar atelectasis; notice the line separating the two shades of gray representing the infiltrate and the fluidConsent obtained at University of Louisville, KY [Citation ends].

Oxygenation status

The preferred method to determine oxygenation status is from an arterial blood gas (ABG) test. An oxygen saturation obtained from a peripheral site may provide a false sense of adequate oxygenation, especially in the context of the signs and symptoms of HAP when vascularization may be constricted peripherally. Obtaining an ABG while the patient is not yet receiving increased FiO₂ provides a more accurate reflection of the oxygenation status, but obviously increased oxygen should not be withheld from any unstable patient.

Gram stain

A Gram stain may be performed from a tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) sample, protected specimen brush sample, or expectorated sputum.[1][57] If a bronchoscopy is planned but antimicrobials are necessary before the procedure is performed, which may prevent pathogens from growing in culture, an endotracheal sample by suction (nonbronchoscopic BAL) or an expectorated sputum should be collected for culture. Some evidence suggests that treatment based on an endotracheal aspirate yields equivalent outcomes to that based on a BAL specimen.[58]

Blood tests

No infectious diagnosis should be made using the leukocyte count alone, but an increased leukocyte count with a high granulocytosis and proportion of bands may be associated with HAP in the context of an opacity on chest x-ray and other signs and symptoms. Leukopenia may indicate more severe disease, or even sepsis.

The role of C-reactive protein (CRP) is minimized in the 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) guidelines for HAP/VAP, where it is recommended that CRP does assist clinical exam when deciding to initiate antimicrobial therapy.[1]

Biomarker-guided antibiotic decision-making

The Food and Drug Administration has approved procalcitonin as a test for guiding antibiotic therapy in patients with acute respiratory tract infections. Studies have found that procalcitonin may help antibiotic decision making in patients with HAP.[59] The 2016 IDSA/ATS guidelines for HAP/VAP specifically state that procalcitonin does not assist when deciding to start antimicrobial therapy, but it should be used when deciding to discontinue this (de-escalate) in patients whose initial diagnosis does not appear to be valid after approximately 3 days of new clinical information.[1]

Evidence from one randomized controlled trial does not support the use of interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-8 concentrations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid to improve antibiotic stewardship in patients with suspected VAP.[60]

MRSA nasal swab

Nasal swabbing is increasingly being used to screen for MRSA in hospital settings. In the context of HAP/VAP, MRSA nasal swab screening can be used to guide de-escalation of empiric anti-MRSA therapy. In one meta-analysis of 22 studies, comprising 5163 participants, the specificity of MRSA nasal swabbing for MRSA VAP was 94%; the negative predictive value was 95%.[61] However, the IDSA guidelines do not include a recommendation on the use of nasal swabs to screen for MRSA in patients with HAP/VAP.[1]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer