Recommendations

Urgent

Wear a face shield and other personal protective equipment according to local protocols.[16][22]

After assessing the patient using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC) approach, if the patient is haemodynamically unstable:

Call for help immediately so that you can start resuscitation urgently and also apply nasal first aid.[6][22]

Signs of acute hypovolaemia might include tachycardia, syncope, or orthostatic hypotension.[10][16]

Tachycardia may be due to hypovolaemia, anaemia, anxiety, or pain

See Shock.

The British Society for Haematology defines major haemorrhage as either:[23]

Acute major blood loss associated with haemodynamic instability (e.g., heart rate >110 beats per minute and/or a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), or

Bleeding that appears controlled but still requires 'massive' transfusion, or is significant due to the patient’s clinical status, physiology, or response to resuscitation therapy.

Manage major haemorrhage according to your local major haemorrhage protocol.[23]

Consider tranexamic acid.[22] The British Society for Haematology recommends tranexamic acid for major haemorrhage due to trauma but makes no specific recommendations for epistaxis. Practice varies widely. When deciding whether to administer tranexamic acid you should consider the benefit and risk to the individual patient, seek senior advice, and consult local protocols where appropriate.[23]

Seek ENT help early if a child or an elderly patient has severe bleeding as they may require aggressive resuscitation and specialist input.

Be cautious in patients who:

Are older[24]

Have clotting disorders or a bleeding tendency[10]

Are on anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication.[10]

Allocate patients with epistaxis to an area of the emergency department where they can be observed closely, as dislodgement of blood clot may sometimes lead to catastrophic bleeding.[6]

Consider the possibility of injury, including asphyxiation (unintentional or intentional), in children aged <2 years with epistaxis.[25]

In practice:

Treat the epistaxis in the first instance but start assessment and procedures with respect to non-accidental injury in parallel.

Immediately inform your senior and the nurse in charge if a child aged <2 years presents with epistaxis and no known trauma or haematological disorders, or if you have any concern about non-accidental injury.

Refer patients as an emergency from primary care to secondary care if any of the following factors are present in relation to:[29]

The bleeding:

Signs of haemodynamic instability

Bleeding is profuse

Bleeding site appears to be posterior

Epistaxis continues after nasal first aid and the facilities and expertise are not available for nasal cautery or packing

A nasal pack is in place (even if bleeding has stopped)

Epistaxis continues after nasal cautery and/or anterior packing (when appropriate expertise and facilities for cautery and packing are available in primary care)

The patient:

Anticoagulant therapy (as a clotting screen will be needed)

The cause provokes concern (e.g., leukaemia/tumour)

An underlying cause is likely (e.g., conditions predisposing to bleeding, such as haemophilia or leukaemia)

Significant comorbidity (e.g., coronary artery disease, severe hypertension, severe anemia)

Children aged <2 years

Frailty or old age.

Key Recommendations

If the patient is haemodynamically stable start first aid measures to control bleeding from the nose.[6][10]

Compress both nostrils so that pressure is applied to the entire lower cartilage of the nose (and possible anterior bleeding sites) for at least 10 minutes, with the patient leaning forwards in an upright position.[6][16]

Establish intravenous access with a large-bore cannula at the same time as taking bloods in:

Older patients

Patients on anticoagulants

Haemodynamic compromise

Profuse bleeding

Bleeding >20 minutes.

After nasal first aid measures, progress to application of topical vasoconstrictor (decongestant) ± anaesthetic to control the bleeding if necessary.[26]

If vasoconstrictor ± anaesthetic does not control the bleeding, and you can identify and access a point of bleeding, cauterise the vessel precisely.[6]

Most junior doctors in the emergency department can become proficient in silver nitrate cautery.

Electrocautery is preferred to silver nitrate cautery if a suitably trained clinician is available.[6][16] In the UK, electrocautery is usually reserved for the ENT consultant and is generally performed in theatre.

If anterior nasal cautery does not control bleeding, use non-dissolvable anterior nasal packing material, such as an inflatable nasal tampon or compressed sponge.[6][26]

Refer your adult patient to ENT if:[6]

Rigid endoscopy or microscopy is needed to identify the source of the bleeding.[6] In the UK, these procedures are usually done by an ENT doctor.

Anterior packing fails to stop the bleeding.[6]

Posterior packing is needed.[6]

Antero-posterior packing is required.

Refer a child patient to ENT if:

Bleeding is severe or difficult to stop

Bilateral anterior packing is needed

Any posterior packing is required.

In practice, if there is likely to be a significant delay before specialist input or the patient’s haemodynamic status is deteriorating, a Foley catheter can be used as an emergency temporary solution for posterior bleeding.

Protect yourself from the high risk of contamination associated with epistaxis due to direct bleeding into the airway and the increased likelihood of droplet spread.

Follow your local protocol, but as a minimum, you should don the following:[16]

Gloves

Mask

Visor (face shield)

Lab coat.

After assessing the patient using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC) approach, if the patient is haemodynamically unstable:[6]

Call for help immediately so that you can start resuscitation urgently and also, if possible, apply nasal first aid.

Signs of acute hypovolaemia might include tachycardia, syncope, or orthostatic hypotension.[10][16]

Tachycardia may be due to hypovolaemia, anaemia, anxiety, or pain (from packing placement or cautery)

See Shock.

The British Society for Haematology defines major haemorrhage as either:[23]

Acute major blood loss associated with haemodynamic instability (e.g., heart rate >110 beats per minute and/or a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), or

Bleeding that appears controlled but still requires 'massive' transfusion, or is significant due to the patient’s clinical status, physiology, or response to resuscitation therapy.

Manage major haemorrhage according to your local major haemorrhage protocol.[23]

Consider administering tranexamic acid according to local protocols.[22]

Seek senior or ENT help early in children and elderly patients with severe bleeding as these patients may require aggressive resuscitation and specialist input.

In addition to stopping the bleeding, monitor vital signs, supplement oxygen, obtain intravenous access, maintain the airway, and support breathing and circulation if required. For more information on resuscitation, see Shock.

Blood, fresh frozen plasma, and platelet transfusion, and fibrinogen supplementation may be needed.[6]

Seek early case-specific guidance from haematology for any patient who:[6]

Is on anticoagulation

Has a coagulopathy

Needs blood transfusion.

Practical tip

Visual quantification of blood loss, either from the patient’s history or blood-stained clothing, is unreliable and blood loss can be underestimated by both medical and non-medical staff.[10]

Practical tip

When deciding whether to administer tranexamic acid you should consider the benefit and risk to the individual patient, seek senior advice, and consult local protocols where appropriate. Practice varies widely. The British Society for Haematology recommends tranexamic acid for major haemorrhage due to trauma but makes no specific recommendations for epistaxis.[23]

Nasal first aid

After assessing the patient, start first aid measures to control bleeding from the nose if the patient is haemodynamically stable.[6]

Ask the patient to lean forward but remain upright and firmly pinch the soft part of the nose compressing both nostrils (and possible anterior bleeding sites) for at least 10 minutes.[6][16]

Encourage the patient to spit out, rather than swallow, any blood passing into the throat (blood is irritating to the stomach and may make the patient nauseous).

Provide an oral ice pack.[6][22]

Alternative, practical options include an ice cube for the patient to suck, cold drinks, or applying an ice pack directly to the nose to reduce nasal blood flow.

Practical tip

Use a swimmer’s nose clip as an alternative technique to apply external pressure on the nostrils.[30]

Supportive care

Establish intravenous access with a large-bore cannula at the same time as taking bloods if indicated, in:

Older patients

Patients on anticoagulants

Haemodynamic compromise

Profuse bleeding

Bleeding >20 minutes.

Allocate patients with epistaxis to an area of the emergency department where they can be observed closely, as dislodgement of blood clot may sometimes lead to catastrophic bleeding.[6]

Control of raised blood pressure

The relationship between epistaxis and hypertension is complex and remains unclear.[10] There is a paucity of evidence and guidance on how and when to treat hypertension in patients with epistaxis.

In practice, if the patient is hypertensive, consider treatment according to hypertension guidelines and discuss a treatment plan with a senior colleague. See Assessment of hypertension.

Practical tip

In the absence of hypertensive urgency/emergency, US guidelines do not recommend routinely lowering blood pressure in patients with acute nosebleed. Interventions to acutely reduce blood pressure can have adverse effects and may cause or worsen renal, cerebral, or coronary ischaemia.[10]

Monitor blood pressure in patients with acute nosebleeds, and base decisions about blood pressure control on:[10]

The severity of the patient's nosebleed

The inability to control the bleeding

Individual patient comorbidities

The potential risks of blood pressure reduction.

If hypertension persists after severe epistaxis, request cardiovascular evaluation to screen for underlying hypertensive disease.[31]

Clear blood using suction, gentle nose blowing, or forceps (be careful not to injure the nasal mucosa). Then apply a topical vasoconstrictor ± local anaesthetic using any of the following methods:[10][26]

Spray

Soaked cotton wool ball

Pledget.

Practical tip

Use topical vasoconstrictors cautiously in patients who may experience adverse effects associated with peripheral vasoconstriction due to alpha-1-adrenergic agonists, for example those with:[10]

Hypertension

Cardiac disease

Cerebrovascular conditions.

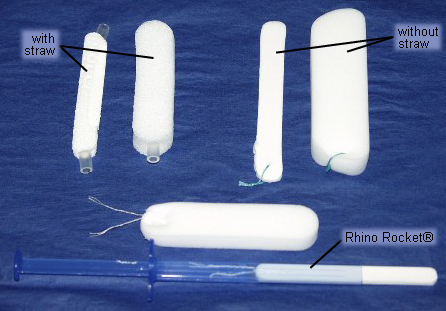

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nasal pledgets for application of decongestant and local anaestheticFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

Practical tip

Active bleeding may prevent proper evaluation, so mucosal vasoconstriction (decongestion) is helpful for diagnosis and management. If bleeding makes administration difficult, ENT doctors may attempt rapidly alternating nasal suction (or nose blowing) with intranasal spraying of oxymetazoline. This may exceed the typical dosage on the manufacturer's label, however active bleeding prevents absorption of much of the medicine, and these larger doses are routinely used without difficulty in nasal surgery via spray and on pledgets.

In practice, if bleeding is severe enough to preclude adequate assessment, avoid persisting too long with repeated alternations between suction and vasoconstrictor administration, and seek senior assistance.

Practical tip

A vasoconstrictor (decongestant) reduces blood flow, shrinks mucosal thickness, and increases nasal space should pack placement be required. This can reduce mucosal trauma and decrease secondary bleeding from disrupted mucous membrane.

Effective pack placement may be compromised if the procedure is painful. Prepare a mixture of lidocaine and oxymetazoline according to local protocols. Some clinicians simply remove the top from a spray bottle of oxymetazoline, add an equal volume of the lidocaine, and replace the top; however, consultant advice is recommended.

Next, saturate small neurosurgical pledgets or strips of cotton with the mixture and place them horizontally in the nose using bayonet forceps. Leave for 10 to 15 minutes while the patient compresses the nose if necessary.

Evidence: Tranexamic acid for initial treatment of epistaxis

Oral or topical tranexamic acid may be beneficial in some adults with epistaxis.

A Cochrane systematic review (search date October 2018) assessed the effectiveness of tranexamic acid in the management of epistaxis.[32]

It found some benefits for tranexamic acid but this was inconsistent and only three studies were post 1995 (since then there has been progress in usual care) so the authors concluded that the role of tranexamic acid remains unclear.

The authors excluded studies in patients with a clotting or bleeding disorder, sinonasal malignancy, or chronic inflammatory nasal conditions.

Overall they included six randomised controlled trials (n=692), all in adults only.

The Cochrane review identified three trials comparing oral or topical tranexamic acid versus placebo (two of oral and one topical).[32]

The two studies of oral tranexamic acid also used nasal packing, in one this was in combination with nasal cautery. The topical study used a gel to fill the nasal cavity.

Tranexamic acid improved the control of epistaxis compared with placebo (measured by rebleeding within 10 days; pooled data from these 3 studies; n=225; risk ratio [RR] 0.71, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.90; moderate-quality evidence as assessed by GRADE).

The results were similar with oral or topical tranexamic acid.

The two studies of oral tranexamic acid reported length of hospital stay. One study reported a significantly shorter stay with tranexamic acid (n=68; mean difference -1.60 days, 95% CI -2.49 to -0.71). The other study found no evidence of a difference between the groups.

No study mentioned significant adverse effects (including thromboembolic events) and none reported the proportion of patients requiring any further intervention such as repacking, surgery, or embolisation.

Although not in patients with epistaxis, a large meta-analysis (search date December 2020) looking at the safety of intravenous tranexamic acid in surgical patients found no increased risk of thromboembolic events.[33]

The Cochrane review identified three trials comparing topical tranexamic acid versus other topical haemostatic agents.[32]

Topical liquid tranexamic acid seemed to be more effective than other topical haemostatic agents at stopping bleeding in the first 10 minutes (3 studies; n=460; RR 2.35, 95% CI 1.90 to 2.92; GRADE moderate).

Two studies used pledgets soaked in adrenaline (epinephrine) and lidocaine as the comparison, and the other phenylephrine poured onto a cotton ball, with tranexamic acid applied in the same way.

All three studies included people with anterior bleeds only.

One subsequent network meta-analysis (search date September 2022) found that topical treatment with tranexamic acid reduced rebleeding within 2 days compared with conservative treatment (odds ratio [OR] 0.36, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.61) or anterior nasal packing (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.76).[34]

Topical tranexamic acid also reduced rebleeding within 7 days compared with traditional nasal packing (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.70).

While topical tranexamic acid seemed to improve immediate haemostasis compared with conservative treatment or anterior nasal packing, the low to very low quality of the evidence meant there was some uncertainty in interpreting these results.

Guidelines differ on the role of tranexamic acid in the treatment of epistaxis.

The ENT UK 2023 global ENT guideline recommends considering oral or intravenous tranexamic acid depending on the extent of bleeding and whether the patient is being treated in a community or hospital setting by a healthcare worker who is not a medically trained doctor, a medical doctor, or an ENT surgeon.[22]

The 2020 US clinical practice guideline on epistaxis does not make a recommendation for or against the use of tranexamic acid, citing the 2018 Cochrane review and the need for further evidence.[10]

Consider cautery as first-line treatment for all acute epistaxis with obvious bleeding points.[6][10]

Only perform cautery:

On a visually identified bleeding point[6]

If you have been suitably trained.[6]

If you can’t identify an anterior bleeding point, rigid endoscopy or microscopy (by a suitably trained and experienced practitioner) may be needed.[6]

In practice, this may require referral to the ENT department, but do not wait for nasendoscopy; pack the nose as soon as possible to control the haemorrhage. The patient can then be referred to ENT for further assessment.

Clear blood in the front of the nose using suction, gentle nose blowing, or forceps.[26] A soft suction catheter is less likely to cause trauma to the nasal lining.

Be aware that patients may have received topical vasoconstrictor ± local anaesthetic during initial treatment. However, ensure adequate application of local anaesthetic ± vasoconstrictor and allow this to take effect before starting cautery; in addition to providing pain relief, this should improve visualisation of the anterior nasal cavity.

Practical tip

Do not cauterise both sides of the septum during the same episode; septal perforation may occur due to decreased perichondrial blood supply.[16]

Cauterise any visible vessel or localised area of bleeding in an adult patient with either one of:

Silver nitrate (75% strength) applied directly to the vessel[26]

Apply for no more than 30 seconds in any one spot.[35]

In practice, most junior doctors in the emergency department can become proficient in silver nitrate cautery.

Electrical cautery.[16]

Electrocautery should be used in preference to silver nitrate cautery if a suitably trained clinician is available.[6][16]

The preference for electrocautery is based on lower treatment failure and recurrence rates, reduced need for nasal packing, and reduced rates of hospital admission when compared with silver nitrate cautery, although the quality of evidence for this is very low.[6] In the UK, this procedure is usually reserved for the ENT consultant and is generally performed in theatre.

Practical tip

What is meant by 'localised area' for nasal cautery has not been clearly defined. In practice, the aim is to identify an active bleeding point and precisely cauterise this area. If bleeding is brisk, ‘doughnutting’ may be an option: cauterise the four quadrants immediately surrounding the vessel to isolate the source and disrupt supply to the bleeding point. Do not cauterise a large area of the mucosa.

Cautery of a vessel that is not part of the Kiesselbach's plexus is not contraindicated, but bleeding from outside this area is rare.

Observe the patient for 15 minutes after cautery to ensure bleeding is controlled before discharge.

Practical tip

Silver nitrate (75%):

Is applied via commercially manufactured sticks or applicators (note that sticks may not be licensed for use on the face in some countries)

Degrades over time, so lack of activity may indicate the need to use fresher silver nitrate

Can stain the skin for weeks or months after nasal cautery if it is not dried adequately, or if there is subsequent nasal discharge.[36] After spraying or applying the vasoconstrictor ± anaesthetic, reduce the risk of staining by:[36]

Drying the area with a cotton bud

Applying silver nitrate from the outside edge of the bleeding point and continuing round in a spiral towards the centre of the bleeding point

Drying around the area after application

Protecting the skin in and around the nostril with antibiotic ointment or soft paraffin.

Consider nasal packing if bleeding continues despite first aid measures, topical vasoconstriction ± local anaesthesia, and cautery (if available), if you can’t identify a specific bleeding point, or if there is bilateral bleeding.[26]

Demonstrates insertion of an inflatable anterior nasal pack and a nasal tampon.

Ensure that you have been trained to use nasal packing.[6]

There are two types of packing:

Dissolvable, which in the UK is generally reserved for ENT departments

Non-dissolvable, which is available as compressed sponge and inflatable balloon tampons. Products commonly used in the UK are:

Rapid Rhino®, an inflatable coated nasal balloon catheter

Merocel®, an absorbent dry sponge tampon.

Practical tip

In practice, do not insert nasal packing in a patient with nasal polyps. If nasal first aid and cautery do not stop the bleeding, refer to ENT.

Non-dissolvable nasal packing

Depending on bleeding severity, pack the actively bleeding nostril or both nostrils.[26] Seek the advice of a senior colleague if bleeding is severe.

In practice:

Different institutions will have experience with specific nasal packs. Follow local preferences.

As epistaxis generally originates on one side, packing is usually unilateral.

However, when the history and examination fail to identify whether the bleeding is from the right or the left, or when packing one nostril does not control the bleeding, both sides of the nose can be packed to provide some counter pressure to the nasal septum.

Seek senior input if you are inexperienced, or not confident with bilateral packing, as nasal septal perforation may occur.[10]

Some patients requiring non-dissolvable packing because of ineffective earlier measures or profuse bleeding may need admission.[26] Consult your local protocol.

Practical tip

Follow the points below to ensure optimal use of anterior nasal packs.

Place all anterior packs as horizontally as possible to avoid misplacement.

Rapid Rhino® and Merocel® packs are equally effective, but Rapid Rhino® may be less painful to insert and easier to remove than Merocel®.[6][40][41]

Traditional ribbon gauze soaked in bismuth iodoform paraffin paste (BIPP) is as effective as nasal tampons, but is more difficult to insert.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Expanding nasal sponge pack in placeFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Anterior-posterior traditional Foley catheter-gauze packFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Anterior-posterior traditional Foley catheter-gauze packFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Expanding nasal sponge tamponsFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Expanding nasal sponge tamponsFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends]. Observe the patient for at least 30 minutes to check there is no bleeding from the nose or into the pharynx.

Observe the patient for at least 30 minutes to check there is no bleeding from the nose or into the pharynx.

Re-examine the oropharynx after inserting the nasal pack as blood may divert posteriorly or you may have missed a posterior source for the epistaxis.

Do not prescribe routine systemic antibiotics after insertion of anterior nasal packs unless they are in place for longer than 48 hours.[6]

If anterior non-dissolvable nasal packing does not control the bleeding, seek senior advice on further management.

Pack removal

Non-dissolvable nasal packs should be removed within 24 hours of insertion if there is no evidence of active bleeding (with leeway for daylight hours).[6]

The nose should then be re-examined and an assessment made as to the need for cautery.[6]

If necessary, rigid endoscopy should be performed to identify and cauterise the bleeding point if this is not evident from anterior rhinoscopy.[6]

Practical tip

When removing a nasal pack:

Apply a mixture of topical vasoconstrictor, such as oxymetazoline, and lidocaine (according to local protocols) to the sponge pack

The vasoconstrictor shrinks adjacent mucosa

The lidocaine provides analgesia

Saturate the pack to promote softening and lubrication to discourage mucosal trauma and re-bleeding.

If epistaxis continues after unilateral or bilateral anterior nasal packing, the bleeding is most likely to be coming from the posterior nasal cavity.

Refer patients with posterior epistaxis to the ENT department for posterior packing, endoscopy with cauterisation, or ligation of the sphenopalatine artery.[6]

Practical tip

If the patient is becoming haemodynamically unstable and there is likely to be a delay before ENT consultation, use two Foley catheters to temporarily control blood loss in the emergency department. Seek senior assistance if you are not experienced in this procedure.

Insert size 12 gauge catheters one at a time through the nostril, along the floor of the nose, and into the nasopharynx until you can see them in the pharynx.

Inflate each balloon with 5 to 10 mL of water and then apply gentle traction to compress the bleeding vessels in the posterior nasal cavity.

Combined non-dissolvable anterior and posterior nasal packs should be considered.[6]

In UK practice, patients needing this level of management usually need senior assessment.

An intravenous opioid analgesic plus an anti-emetic (e.g., ondansetron) are usually required before posterior packing because it can be very painful or uncomfortable.

Use opioids with caution in older and shocked patients.

Follow local post-packing observation protocols.

Because of risk of hypoxia, some hospitals require observation of patients with posterior packing in the intensive care unit; others consider this appropriate specifically for older people and patients with comorbidities.

Uncertainty exists about the need for routine antibiotic cover for posterior packs.[6] Consult your local protocol.

Options for posterior packing

A variety of options exist; the following methods are commonly used in ENT departments in UK practice.

Double-balloon epistaxis device

Commercially available, double-balloon catheters have a 15 mL distal balloon (similar to that of a Foley catheter) for the posterior packing component, and a proximal 30 mL balloon to provide anterior packing and occlude the nostril.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Deflated and inflated double-balloon nasal catheterFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Double-balloon nasal catheter in placeFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Double-balloon nasal catheter in placeFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

Traditional gauze anterior pack with posterior urinary catheter

The Foley-type urinary catheter is probably the easiest way to place a traditional anterior pack posteriorly.

Lubricate a size 12 French catheter with petroleum jelly, antibiotic ointment, or water-based lubricant jelly, pass it to the nasopharynx and inflate the balloon with 7 to 8 mL of water.

Ask an assistant to maintain a steady anterior pull to lodge the catheter in the posterior choana while you insert a traditional gauze pack anteriorly. Wrap gauze around the catheter and secure an umbilical clamp against the gauze to maintain adequate tension.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Anterior-posterior traditional Foley catheter-gauze packFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

Surgery and interventional radiology are effective in managing epistaxis that has not responded to first aid and nasal packing, or if bleeding recurs when adequate packing is removed.[6]

Endoscopic examination of the nose with or without cautery, as appropriate

Sphenopalatine artery ligation

Anterior ethmoid artery ligation (if traumatic)

Embolisation.

If the patient is not fit for surgery, or surgery is not available and anterior nasal packing does not control the bleeding, insertion of posterior non-dissolvable nasal packing with a Foley catheter and traditional ribbon gauze impregnated with bismuth iodoform paraffin paste (BIPP), or another anterior non-dissolvable pack, should be considered.[26]

Prescribe oral analgesics for discomfort associated with chemical or electrocautery, nasal packing, and more advanced procedures according to your local pain score or pain ladder protocol.

Paracetamol is usually appropriate.

DO NOT prescribe a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen to a patient on anticoagulation or to older people.

In practice, you can prescribe a single dose of an NSAID for most other patient groups with epistaxis.

Opioid analgesics may be necessary in some patients. An intravenous opioid analgesic (plus an anti-emetic such as ondansetron) is usually required before posterior packing because it can be very painful or uncomfortable.

Use opioid analgesics with caution in older and shocked patients.

Avoid medications containing aspirin.

Consider whether your patient needs admission. In practice, if bleeding is controlled by first aid measures and topical agents, most patients can be discharged home.

Do not routinely admit patients if they are stable 4 hours after pack removal or cautery.[6]

Admission is recommended for patients with bleeding that is not controlled by anterior nasal packing, or which is profuse (depending on local policy).[26]

Most patients with epistaxis controlled by cautery or anterior tampon packing do not need hospital admission.[42]

Admission and further observation may be needed in patients with anterior packs in place and:[43]

Shock

Haemodynamic instability

Haemoglobin <10 g/dL

Anticoagulant medication

Recurrent epistaxis following a previous episode requiring nasal packing within the last 7 days

Uncontrolled hypertension

Significant comorbid illness

Difficult social circumstances

Suspected posterior bleed (bleeding is profuse, from both nostrils, and the bleeding site cannot be identified on examination).

Seek early case-specific guidance from haematology in patients who are on any anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy and have epistaxis.[6]

Practical tip

In practice, if the patient is on anticoagulation and epistaxis is difficult to control, consult with haematology for consideration of dose adjustment, dose omission, or even anticoagulation reversal.

This is especially relevant where the international normalised ratio (INR) is out of normal range and clotting is prolonged.

Refer as an emergency from primary care to secondary care if the following factors exist in relation to:[29]

The bleeding:

Signs of haemodynamic instability

Bleeding is profuse

Bleeding site appears to be posterior

Epistaxis continues after nasal first aid and the facilities and expertise are not available for nasal cautery or packing

A nasal pack is in place (even if bleeding has stopped)

Epistaxis continues after nasal cautery and/or anterior packing (when appropriate expertise and facilities for cautery and packing are available in primary care)

The patient:

Anticoagulant therapy (as a clotting screen will be needed)

The cause provokes concern (e.g., leukaemia/tumour)

An underlying cause is likely (e.g., conditions predisposing to bleeding, such as haemophilia or leukaemia)

Significant comorbidity (e.g., coronary artery disease, severe hypertension, severe anemia)

Children aged <2 years

Frailty or old age.

In hospital, call for senior help if:

Anterior packing fails to stop the bleeding[6]

Posterior nasal packing is needed[6]

OR

Any of the following apply (based on the opinion of our expert):

You are unsure of the source of the bleeding

You cannot stop the bleeding

You have not been trained in any of the procedures needed

Bilateral anterior packing is indicated, as this carries a risk of nasal septal perforation[10]

Antero-posterior packing is required

A polyp or tumour is present, as these will require further assessment and management, usually by ENT

A foreign body is present (the foreign body should be removed, usually by ENT, prior to attempting to control the bleeding).

Patients requiring additional measures need ENT referral. The ENT doctor may:[6]

Perform rigid endoscopy or microscopy if needed to identify the source of the bleeding

Recurrent epistaxis requires further assessment and management outside of the acute setting.

Administer electrocautery

Conduct advanced surgical procedures

Consider interventional radiology if appropriate.

Discuss your patient with haematology if:[6]

You suspect a bleeding diathesis such as haemophilia or leukaemia

Your patient is on anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy

Transfusion of blood products may be needed.

Following pack removal or cautery, discharge clinically stable patients after 4 hours.[6]

Prescribe a suitable topical antibiotic cream (e.g., chlorhexidine/neomycin, mupirocin) or petroleum jelly for 7 days.[26]

No follow-up is necessary for patients whose epistaxis has:

Stopped spontaneously

Been controlled by first aid measures

Responded to cautery.

Provide advice to:

Prevent recurrence of the nosebleed, such as:[10]

Avoiding aspirin and ibuprofen or other NSAIDs

Avoiding straining, bending over, and strenuous exercising (although walking and other gentle activity is permitted)

Refraining from nose blowing

Sneezing with the mouth open

Sleeping with the head slightly raised

Help the patient administer nasal first aid measures in the future.

See Patient discussions.

Arrange an ENT follow-up appointment for patients discharged with an anterior nasal pack. The ENT department should remove the pack within 24 hours (with leeway for daylight hours) and can assess whether cautery is necessary.[26]

Refer patients with an underlying condition predisposing to epistaxis (including primary bleeding disorders, haematological malignancies, intranasal tumours, or vascular malformations) for appropriate follow-up.[10]

This section covers management aspects that are pertinent to children. Please also review any relevant sections above for general information about management of epistaxis in all age groups.

Urgent considerations

Consider the possibility of injury, including asphyxiation (unintentional or intentional), in children aged <2 years with epistaxis.[25]

In practice:

Treat the epistaxis in the first instance, but start assessment and procedures with respect to non-accidental injury in parallel.

Immediately inform your senior and the nurse in charge if a child aged <2 years presents with epistaxis and no known trauma or haematological disorders, or if you have any concern about non-accidental injury.

Seek an early senior or ENT opinion for any child with epistaxis that is severe or difficult to stop.

Nasal first aid

During nasal first aid:

Children should sit comfortably, possibly on their parent’s lap so that the parent can assist if necessary with firm compression of the lower part of both nostrils for at least 10 minutes.

Encourage the child to breathe through their mouth.

Topical agents

Vasoconstrictors and anaesthetics should be used with caution in young children, whether used to improve visualisation or to control the bleeding.[10][44]

Adequate first aid measures usually stop epistaxis in children and examination of the anterior nasal cavity will commonly reveal either crusting of the anterior nasal mucosa or a visible vessel.

While most experienced clinicians report that moisturisers and lubricants such as nasal saline, gels, and ointments and use of air humidifiers can help prevent nosebleeds, high-quality evidence to support these treatment strategies is scarce.[10]

In practice, treat children with recurrent nosebleeds and nasal crusting with topical nasal antibiotic cream for 4 weeks to prevent further bleeding.

Anterior nasal cautery

In children, chemical cautery is preferred to electrocautery because electrocautery is more painful and requires a general anaesthetic.[16]

Consult a senior colleague if cautery is required.

Do not attempt cautery in a child aged <4 years as cooperation is unlikely and sedation is not recommended due to risk of inhalation of clots, packing, or local anaesthetic agents.

Evidence: Recurrent epistaxis in children

Limited evidence shows no difference in efficacy for different treatments for recurrent idiopathic epistaxis in children; although for nasal cautery 75% silver nitrate is more effective in the short-term, and less painful, than 95% silver nitrate.

A Cochrane systematic review (search date March 2012) on the treatment of recurrent epistaxis in children identified five studies (four randomised controlled trials [RCTs] and one quasi‐randomised controlled trial; n=468).[45] All took place in a specialist setting (otolaryngology clinic/department).

One double-blind RCT (n=103, low risk of bias) compared 75% versus 95% silver nitrate nasal cautery.

Complete resolution of epistaxis at 2 weeks post-treatment was better with 75% silver nitrate (88% vs. 65%, P=0.01). However, there was no difference at 8 weeks.

Children in both groups found cautery painful, even though local anaesthetic was used routinely; however, 75% silver nitrate was less painful (mean score 1 versus 5; P=0.001).

One double-blind RCT (n=109, unclear risk of bias) compared silver nitrate cautery plus antiseptic nasal cream versus antiseptic nasal cream alone.

There was no difference in effectiveness to control epistaxis.

One child developed a rash with the antiseptic nasal cream and had to discontinue treatment. Transient discomfort was reported with nasal cautery.

One single-blind RCT (n=103, unclear risk of bias) compared antiseptic nasal cream versus no treatment.

There was a significant loss to follow-up (14.5%) with no difference in effectiveness between the interventions in the Cochrane intention-to-treat analysis.

No data on adverse events were reported.

One single-blind RCT (n=105, low risk of bias) compared petroleum jelly versus no treatment.

There was no difference in effectiveness to control epistaxis. No data on adverse events were reported.

One quasi‐randomised controlled trial (n=48, high risk of bias) compared antiseptic nasal cream versus silver nitrate cautery.

There was no difference in effectiveness to control epistaxis. No data on adverse events were reported.

Overall the evidence was limited and the authors concluded that the optimal treatment remained unclear, although 75% silver nitrate should be used for nasal cautery.

Evidence-based guidelines, NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries (NICE CKS), and the 2020 American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) clinical practice guideline on epistaxis cite this Cochrane systematic review as the underlying evidence for the management of recurrent epistaxis in children.[10][46]

The AAO-HNS guideline recommends silver nitrate cautery, using local anaesthetic, when the bleeding site can be identified.[10]

If these measures fail, nasal packing may be required, although this is rarely needed in children.

Admission

In UK practice, all children with nasal packs are admitted for observation because of the risk of airway compromise.

Referral indications

Alert your senior and the nurse on call for any child aged <2 years presenting with epistaxis without a known injury or bleeding disorder.

Epistaxis is rare in this age group and is associated with accidental and non-accidental asphyxia.[25]

See Child abuse.

Discharge and follow-up

If a child has needed nasal packing, admit for 48 hours and remove the nasal pack prior to discharge.

If simple measures stop epistaxis, discharge the child with education on management at home and preventative measures such as avoiding hot drinks, food, baths, or showers for at least 24 hours, no nose-blowing for one week and no nose-picking. See Patient leaflets.

If the child has had cautery or received packing, or has dry, cracked mucosa, advise the parent to apply petroleum-based gel for one week.

Avoid long-term use of petroleum-based gel because of the risk of chemical pneumonitis if it is inhaled.

Consider prescribing a topical antibiotic ointment for 4 weeks if there is nasal crusting and the mucosa appears infected.[43]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer