Recommendations

Urgent

Wear a face shield and other personal protective equipment according to local protocols.[16][22]

Consider epistaxis as a possible circulatory emergency depending on the severity of the bleed, the ability of the patient to tolerate hypovolaemia, and the presence of factors that may make it difficult to control the bleeding.[6][16]

Assess any patient who presents with ongoing or recently resolved bleeding using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC) approach.[6]

The British Society for Haematology defines major haemorrhage as either:[23]

Acute major blood loss associated with haemodynamic instability (e.g., heart rate >110 beats per minute and/or a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), or

Bleeding that appears controlled but still requires 'massive' transfusion, or is significant due to the patient’s clinical status, physiology, or response to resuscitation therapy.

Urgently resuscitate patients with any signs of acute hypovolaemia, including tachycardia, syncope, or orthostatic hypotension.[10]

Manage major haemorrhage according to your local protocol.

See Shock.

In practice:

Be particularly cautious in patients who:

Seek senior or ENT help early in children and older patients with severe bleeding as they may require aggressive resuscitation and specialist input.

Consider the possibility of injury, including asphyxiation (unintentional or intentional), in children aged <2 years with epistaxis.[25]

In practice:

Treat the epistaxis in the first instance but start assessment and procedures with respect to non-accidental injury in parallel

Immediately inform your senior and the nurse in charge if a child aged <2 years presents with epistaxis and no known trauma or haematological disorders, or if you have any concern about non-accidental injury.

Key Recommendations

Epistaxis is usually from Little's area, which is on the septal wall anteriorly.[10]

Start nasal first aid measures while taking a history and examining the patient.[6][10]

Ask about:

The nature of the bleeding, including the side and site that the bleeding started[6]

Trauma (nosebleed associated with significant trauma is not covered in this topic)

Bleeding or bruising elsewhere on the body[6]

Important risk factors that increase the likelihood of epistaxis and/or indicate the possibility of a worse outcome. These include:

Clear blood to improve visibility before examining the patient’s nostrils and oropharynx.[26]

Applying a topical vasoconstrictor ± local anaesthetic, using a spray, soaked cotton wool balls, or pledgets, can aid visibility and identification of an anterior bleeding site (as well as helping with control of bleeding and pain).[6]

Blood tests are usually unnecessary, unless the patient is haemodynamically unstable, blood loss has been significant, or the patient is elderly, has a clotting disorder, bleeding tendency, or is on an anticoagulant.[6][16] In such scenarios:

Send blood for a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, and ‘group and save’.[6][16] Request clotting studies if the patient:

Cranial imaging (computerised tomography in the first instance) may be necessary if you suspect a neoplasm. Seek senior advice.

Consider epistaxis as a possible circulatory emergency depending on the severity of the bleed and patient risk factors.[6][16]

Assess any patient with a history of bleeding using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC) approach.[6]

The British Society for Haematology defines major haemorrhage as either:[23]

Acute major blood loss associated with haemodynamic instability (e.g., heart rate >110 beats per minute and/or a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), or

Bleeding that appears controlled but still requires 'massive' transfusion, or is significant due to the patient’s clinical status, physiology, or response to resuscitation therapy.[23]

Check your local major haemorrhage protocol for locally defined parameters.[23]

Urgently resuscitate patients with any signs of acute hypovolaemia, including tachycardia, syncope, or orthostatic hypotension.[10]

Manage major haemorrhage according to your local protocol.

See Shock.

In practice:

Be particularly cautious in patients who:

Seek senior or ENT help early in children and older patients with severe bleeding as they may require aggressive resuscitation and specialist input.

The presenting problem is usually obvious, with blood at one nostril or on both sides of the nose.

Epistaxis is usually from Little's area, which is on the septal wall anteriorly.[10]

Start nasal first aid (see the Management section) while taking a history and examining the patient.[6][10]

Ask for information about the current episode of epistaxis, including:

The nature of the bleeding, which will help you determine the urgency of treatment:

The site and side the bleeding started:[6][22]

Blood starting at the nares suggests an anterior site for the source of the bleeding

Blood starting from the throat suggests a posterior site for the source of the bleeding

The estimated amount of blood loss, although this may be difficult for the patient to assess[10]

History of trauma (nosebleed associated with significant trauma is not covered in this topic)

The presence of bleeding or bruising elsewhere on the body, which may indicate a coagulopathy[6]

Alcohol intake, which may affect clotting mechanisms.[16]

Practical tip

In practice, anterior epistaxis quickly causes blood in the pharynx, so establishing whether a bleed started in the front or down the throat is helpful. Although a patient may report that the bleeding originated high up or in the back of the nose, it is worth remembering that 90% of nosebleeds occur from the anterior septum.[16]

If a nosebleed starts during sleep or when supine, most or all of the blood drains to the throat, whether originating anteriorly or posteriorly.

Risk factors

Ask about (and document) potential risk factors, including:

Age:

Epistaxis is more common in children and older people.[10]

Environmental:

Cold, dry, low humidity weather, or marked variations in air temperature and pressure.[16]

Local nasal:

Minor trauma, such as nose picking or rubbing[10]

Rubbing, sneezing, coughing, or straining can precipitate epistaxis in children

Recent upper respiratory tract infection, rhinitis, or rhinosinusitis causing mucosal friability

Corticosteroid nasal spray causing friable nasal mucosa[16][17]

Drug misuse (particularly cocaine).[10]

Increased risk of bleeding:

Comorbidities that may affect the patient’s response to a bleed or indicate that they may be on antithrombotic therapy:

General

Be aware that epistaxis is associated with a high risk of blood contamination.[27][28]

Bleeding directly into the airway increases the likelihood of droplet spread.

Wear a face shield and other personal protective equipment according to local protocols.[16][22]

Assess and manage the bleeding at the same time as administering nasal first aid.[10]

Assess the patient’s cardiovascular and respiratory state using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC) approach.[6]

Start resuscitation and nasal first aid immediately if there are signs of acute hypovolaemia, including tachycardia, syncope, or orthostatic hypotension.[10]

Look for evidence of a pre-existing coagulopathy. Signs of a coagulopathy include:

Petechiae

Purpura

Hepatosplenomegaly

Lymphadenopathy.

Local area

Examine the patient’s:

Nostrils. You will need:

In practice, Frazier suction is recommended.

Nasal speculum[10]

A bowl to catch blood (should the examination cause more blood loss)

In practice, blood is usually found in one nostril or on both sides of the nose by the time a patient presents with active epistaxis.

Oropharynx, with the help of a tongue depressor, to assess for posterior epistaxis.[22]

Practical tip

In practice, if you don’t have a nasal speculum, gently elevate the tip of the nose with a finger - it may give a reasonable view of the front of the nasal cavity.

Clear any blood to improve visibility by:[26]

Asking the patient to blow their nose gently

Using suction at the nasal orifice

In practice, Frazier suction is recommended.

Removing blood clots with forceps.

In practice, a soft suction catheter is less likely to cause trauma to the nasal lining.

Apply a topical vasoconstrictor ± local anaesthetic using any of the following methods:[6][26]

Spray

Soaked cotton wool balls

Pledgets.

Active bleeding may impede proper evaluation so mucosal vasoconstriction (decongestant) is helpful for both diagnosis and management.

Local anaesthetic improves patient comfort during examination and subsequent treatment.

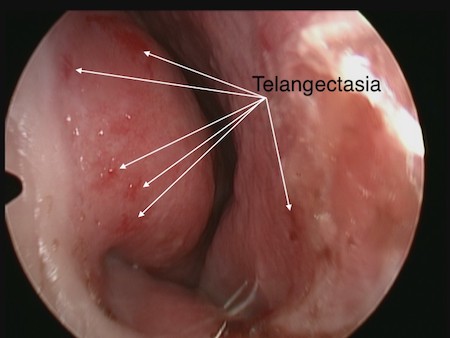

Look for local features that increase the likelihood of epistaxis, such as an intranasal foreign body, an intranasal polyp, a tumour, telangiectasia, septal deviation, or skin ulceration around the nose.

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an autosomal dominant genetic disease leading to arteriovenous malformations and telangiectasias, causing recurrent epistaxis in >90% of people with the condition.[10]

Look for, or enquire about, associated features such as:[10]

Multiple telangiectasias of the face, lips, oral cavity, nasal cavity, and/or fingers

Arteriovenous malformations in the lungs, liver, gastrointestinal tract, or brain

HHT in first-degree relatives.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple telangiectasias visible on nasal examinationImage used with permission from BMJ 2019;367:l5393 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5393 [Citation ends].

Check if the site of the bleeding is anterior using the nasal speculum, the light source, and suction, if necessary.[22] Seek input from ENT if you are unable to identify an obvious anterior bleeding site and anterior packing fails to control the bleeding (see the Management section), as the patient will require nasendoscopy.[6]

Do not wait for nasendoscopy, however; pack the nose as soon as possible to control the haemorrhage. The patient can then be referred to ENT for further assessment.

Base your diagnosis on the patient history and examination.

Do not order blood tests routinely.[6][16]

Have a low threshold for requesting a full blood count, urea, creatinine and electrolytes, and ‘group and save’ (e.g., if the patient is haemodynamically unstable, has had significant blood loss, is frail and elderly, has a clotting disorder or bleeding tendency, or is on anticoagulation).[6][16]

Haemoglobin and haematocrit are usually normal, but may be low if blood loss is recurrent, prolonged, or profuse.

Urea and electrolytes may be abnormal in liver or kidney disease, or with volume depletion.

‘Group and save’ is essential preparation should blood transfusion become necessary.

Request clotting studies if the patient:

Is on anticoagulant medication - check for over-anticoagulation[6][16]

Has chronic liver disease or chronic kidney disease, because of the association with bleeding tendency.[10]

Clotting studies will be abnormal if there is a coagulopathy; INR is usually normal, but may be raised if coagulopathic or if the patient is over-anticoagulated.

Consider other blood tests and ECG depending on comorbidities.

In practice, only request liver function tests if the patient has chronic liver disease, you are concerned about the patient's general medical condition, or if there are unexplained clotting abnormalities.

Raised gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels can indicate high alcohol intake.

Consider imaging depending on comorbidities. It is usually not needed.

Request cranial imaging to exclude neoplastic disease, such as juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, which typically occurs in adolescent boys with unprovoked, profuse, unilateral recurrent epistaxis.[10] This may be associated with unilateral nasal obstruction.

Seek senior or ENT advice regarding any need for cranial imaging. A CT scan is generally the first option, with consideration of an MRI depending on initial findings. Findings on CT scan may be normal; or may demonstrate:

Fracture

Expansile, erosive process suggesting neoplasm

Sinus opacification if sinusitis or neoplasm is present

Intranasal soft-tissue density if polyposis exists.

This section covers diagnostic aspects that are pertinent to children. Please also view any relevant sections above for general information about diagnosis of epistaxis in all age groups.

Child safeguarding

Consider the possibility of injury, including asphyxiation (unintentional or intentional), in children aged <2 years with epistaxis.[25]

In practice:

Treat the epistaxis in the first instance, but start assessment and procedures with respect to non-accidental injury in parallel.

Immediately inform your senior and the nurse in charge if a child aged <2 years presents with epistaxis and no known trauma or haematological disorders, or if you have any concern about non-accidental injury. The case will be escalated to designated child protection leads depending on risk assessment and according to your local non-accidental injury protocol.

History

Ask whether the patient has recurrent nosebleeds and how they are usually treated.

Occasional self-limited epistaxis is common and probably non-specific.

Recurrent significant nosebleed suggests anterior vessel on affected side.

Recurrent nosebleeds are common in children.[10]

Ask about general risk factors (see Risk factors in the main History section above). In addition, factors of particular relevance to children include:

Nose picking[10]

Foreign body.[10]

In practice, the most common presentation of a foreign body is a unilateral, foul-smelling nasal discharge.

Examination

In addition to examining for signs as above (see the main Examination section above), look for a foreign body or staphylococcal colonisation of the anterior nasal cavity causing mucosal crusting.[10]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer