Authors: Yetsa A. Tuakli-Wosornu, Kirsty Burrows, Daniel Rhind

Introduction

Success in elite sport has historically been defined by athletic achievement alone(1,2). Each Olympiad, countries present their best competitors to the world and are largely judged by their medal success. However, recent editions of the Olympic and Paralympic Games have seen a shift: against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Tokyo Games changed the conversation about elite sport to include mental health(3,4); and amidst an unprecedented degree of interest and activity within diverse global agencies, the Paris Games could change the conversation again, this time to spotlight safeguarding.

Recent scholarly and popular press publications demonstrate a surge of interest in interpersonal violence (IV) prevention and safeguarding in sport(5,6). What is clear is that numerous interrelated personal and environmental factors create the conditions that either prevent or promote IV in sport(7). Using a socio-ecological lens, this blog reviews recent updates from influential sport and non-sport authorities related to safeguarding and introduces an updated socioecological model of IV in sport developed by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in the context of a forthcoming consensus statement on the topic.

Global safeguarding updates in sport across five socioecological levels

Advancing a more holistic conceptualization of abuse in sport and acknowledging the reciprocal influence between sportspeople and their environments, the forthcoming consensus statement demonstrates that a whole-of-system approach is needed to fully grasp and prevent IV in sport(8).

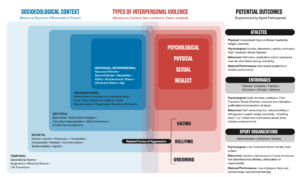

The new socioecological model of IV in sport (Figure 1) visually communicates the complexities between the types of violence, their socioecological contexts, and the potential outcomes across varying scales. An overlapping gradation of color is employed to imply the diffusive nature of categories and to show the ripple effect of relationships and behaviors while also establishing hierarchy. The complementary blue and red colors set up contrasting psychological responses. The sans serif typefaces strive for legibility, readability and clarity. All design elements are compliant with IOC brand standards.

Figure 1: The new socioecological model of IV in sport

Societal and temporal levels

At societal and temporal levels, the salience of IV as a significant issue which merits urgent attention has been seen across industries, including entertainment, business, politics and religion. The #MeToo movement has created a culture in which experiences of harassment and abuse are being disclosed, and listened to, more readily. This shift in the public’s consciousness can create the context in which the rationale for sport safeguarding is more widely understood and supported(9). Indeed, key thought leaders from beyond sport have highlighted the importance of safeguarding in sport. For example, the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Violence Against Women and Girls, Reem Alsalem, recently called for a global consultation on violence against women and girls in sports.

Sectoral and organizational levels

There are also shifts at the sectoral level, with global sport organisations taking important steps. Safe Sport International recently launched their International Safeguards for Adults in Sport, which work in tandem with the child version. The Centre for Sport and Human Rights also announced that it is building a safeguarding toolkit. Within the IOC, a Trauma Informed Investigation of Safeguarding Concerns in Sport, an International Classification Tool, and the IOC Safe Sport Framework–a set of harmonized standards that draw on existing international standards and sets out the complementary but differentiated roles of states and sports bodies endorsed by the Olympic Movement—are under development. At the Paris Games, an AI-enabled cyber-abuse detection tool has been successfully deployed. From an evidence perspective, the IOC will release its most recent consensus statement on IV and safeguarding in sport following a more comprehensive conceptual model (Figure 1).

Individual/Interpersonal level

From a personnel perspective, the IOC Certificate Safeguarding Officer in Sport course has now trained over 250 people from over 80 countries. This is a 7-month online course designed to equip Safeguarding Officers with the knowledge, skills and confidence to be effective in their roles.

Regionally, the IOC announced in 2023 a 10-million-dollar fund per Olympiad and the creation of the Safe Sport Regional Hub Initiative to improve collaboration between local stakeholders in the sporting and non-sporting safeguarding ecosystems, facilitate access to trusted guidance and support for those harmed by IV in sport, and ensure localised prevention. The Pacific Islands and Southern Africa will be targeted initially, where evidence of strong collaboration between continental and regional sporting bodies, intergovernmental organisations and civil society facilitate proof-of-concept.

Discussion

Significant change is happening across all levels of society such that we have reached a tipping point in the way in which safeguarding in sport is viewed, supported and operationalized. These developments may signal a sea-change in the perceived relevance, importance, and urgency of IV prevention in sport at sport’s highest levels. Given this groundswell, there is potential for safeguarding to transform from an abstract ideal into an actionable reality that is well within reach for all who participate in sport.

To send a clear message with appropriate relevance and authority to all readers, the authors of this editorial wish to flag a familiar common ground: most people in and around sport, from athletes to parents to coaches to media, have a subjective connection to it. Most have played, watched, coached, or cheered. This opens an opportunity for readers to take a moment to think about how they can help promote safe sport. Remember why most of us pursue sport in the first instance. This and similar thought exercises quickly summon the qualitative features of responsible sport that effective safeguarding research, policy, and practice rely on: camaraderie, joy, teamwork, belonging, and associated virtues. All of us must more readily recognize our own felt sense of safe sport, individually, within groups, and as part of sports organizations. This may be expressed through healthy relationships between individuals, groups, organisations, and generations, working together. This degree of relational health (and indeed, wealth), multi-scale, -layered, and -disciplinary, may be what is needed to ensure everybody in sport thrives.

We conclude by issuing a call to all sport participants to reject a purely performance-oriented approach to elite sport and follow the burgeoning paradigm, where human achievement and sporting success are embodied, while safeguarding is equally prioritized. It is the right time for safeguarding to step up on to the podium, take centre stage, and strengthen the Olympic flame.

References

- Oakley B, Green M. The production of Olympic champions: International perspectives on elite sport development systems. Eur J Sports Manag. 2001;83–105.

- Green M, Oakley B. Elite sport development systems and playing to win: uniformity and diversity in international approaches. Leis Stud. 2001 Jan;20(4):247–67.

- Tuakli-Wosornu YA, Darling-Hammond K. Unapologetic refusals: Black women in sport model a modern mental health promotion strategy. Lancet Reg Health – Am. 2022 Nov;15:100342.

- Thompson KG, Carter G, Lee ES, Alshamrani T, Billings AC. “We’re Human Too”: Media Coverage of Simone Biles’s Mental Health Disclosure during the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Electron News. 2022 Sep;16(3):187–201.

- Gillard, A., Mountjoy, M., Vertommen, T., Radziszewski, S., Boudreault, V., Durand-Bush, N., … & Parent, S. The role, readiness to change and training needs of the athlete health and performance team members to safeguard athletes from interpersonal violence in sport: a mini review. F. Front Sports Act Living [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 23];6. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sports-and-active-living/articles/10.3389/fspor.2024.1406925/full

- Lang M, editor. Routledge handbook of athlete welfare. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge; 2021. (Routledge international handbooks).

- Roberts V, Sojo V, Grant F. Organisational factors and non-accidental violence in sport: A systematic review. Sport Manag Rev. 2020 Jan 1;23(1):8–27.

- Kerr G, Battaglia A, Stirling A. Maltreatment in Youth Sport: A Systemic Issue. Kinesiol Rev. 2019 Aug 1;8(3):237–43.

- Abrams M, Bartlett ML. #SportToo: Implications of and Best Practice for the #MeToo Movement in Sport. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2019 Jun;13(2):243–58.