Exploring the rationale behind the heading ban in children and adolescent football in the UK

In July 2022, the English FA announced a trial for banning the act of heading in matches for the age groups under-12 and below for the 2022-23 season (1). This has since been extended to the 2023-24 season, in an attempt to gain more evidence for a proposal to the IFAB aimed at scrapping heading altogether. This move follows a previous ban on heading in training for the same age groups.

The rationale behind the banning of heading is to help combat the positive correlation between football and neurodegenerative disease that has become apparent over recent years (2). While it is bound to upset football purists, the decision may have a strong argument medical and safety point of view – this blog aims to explore the potential reasons why.

The Link Between Football and Neurodegenerative Disease

There has long been a suspected link between neurodegenerative disease and football, specifically with heading. This includes both acute injury (concussions) and chronic disease (dementia, CTE; Figure 1).

Figure 1. A timeline of a few key landmarks in the field of chronic neurodegenerative disease and football

Chronic Disease and Football

With the increase in notable former players diagnosed with dementia, including 1966 World Cup winners Bobby and Jack Charlton, as well as Manchester United icon Denis Law, interest in this area has rapidly grown in recent years. So, what’s the evidence behind dementia and playing football?

- Mortality due to neurodegenerative disease and the prescription of dementia-related medication is significantly higher in former players (3,4).

- The risk of neurodegenerative disease is higher in outfield players than goalkeepers, who are at no greater risk than the normal population (4).

- Risk of neurodegenerative disease increases with the length of career (5).

- The prescription of dementia-related medication is significantly higher in former players. It is also higher in outfield players than goalkeepers (3).

- Number of years exposure to a contact sport, rather than number of concussions, is the most closely associated with tau pathology in CTE, suggesting repetitive head impacts, such as heading a football, are more important in development of disease (6).

In summary, players in positions more likely to head the ball, with longer careers and cumulative exposure to the repetitive head impacts heading entails, are more likely to develop neurodegenerative disease later in life.

Concussion and Football

Concussion is another area that has gained a lot of traction within the field of sports medicine, especially with the success of new measures introduced in other sports. This includes the well-established concussion substitute rule in rugby union, where a player can be temporarily taken off to undergo an HIA for suspected concussion, a step that has also been taken in other sports such as cricket more recently. Even within football, recent changes have been made by the FA to their concussion guidance. As a result, this correlation has been extensively researched in recent years, with the important points below:

- Most concussive injuries in football are due to head-to-head contact rather than ball to head contact (7).

- Concussion due to head impact is caused by forces that result in head accelerations – heading a ball results in head accelerations of less than 10g, whereas the minimum required for SRC is generally 40-60g. The average head-to-head impact is typically around 25-30g (8,9).

- Players that play in positions where heading is common also have an increased risk of head-to-head collisions, mostly in aerial duels (7).

- Heading the ball can result in sub-concussive impacts – and repeated heading can contribute to cognitive impairment as a separate risk factor to concussion (10).

Given these findings, we can broadly say head-on-head impact is more likely to cause acute head injury in the form of concussion, while the sub concussive impact of repeatedly heading the ball is the primary pathology for chronic neurodegenerative disease. However, banning the act of heading in matches and training significantly lowers the likelihood of either of these impacts occurring, thereby reducing the risk of brain injury, both in the acute and chronic phase.

Why Children and Adolescents?

One of the major questions surrounding the trial of the heading ban was why is it being tested in children? One could argue that it would be better tested in adults, where headers are more of a staple of the game, rather than in age groups where the majority of players struggle to lift the ball past waist height?

However, there are a number of reasons why the FA decided to proceed with a youth age-group football ban, both for the short and long term:

- Children have less developed skulls

Youth players have smaller heads, as well as less neck and trunk strength to stabilise the head. The weaker isometric strength leads to the brain experiencing relatively greater angular acceleration forces from heading than the adult brain (11).

- Children are less likely to understand proper heading technique

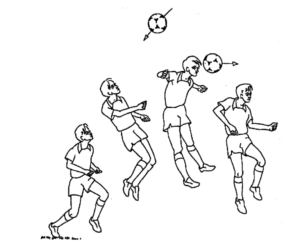

Youth players, especially under the age of 12, are unlikely to have had any formal teaching on the proper technique of heading a football (Figure 2). The poorer form results in a less efficient energy transfer from the head to the ball, again resulting in greater angular acceleration on the head (11). This issue has also prompted further measures, such as initial heading training with a sponge ball, with proper balls introduced once players have developed the basic technique (12).

Figure 2. A drawing representing correct basic heading technique (13) – this is usually the first method of heading taught to players, which then serves as a base to develop specific types of heading (attacking, clearing, diving etc.)

- Getting ahead of the new generation

This measure is with the intention of prevention rather than treatment. Older children and adults may already have some degree of neurodegenerative damage, whereas younger children have not yet been exposed to the head impacts – making them an ideal population to start the trial in.

Conclusion

- Concussion is usually as a result of head-to-head contact, while chronic neurodegenerative disease typically results from repeated sub concussive impacts from heading a ball.

- Playing in a position where heading is more common increases the risk of both head-to-head contact and repeated head-to-ball contact, thereby increasing risk of both chronic disease and concussion.

- Less developed bodies and improper technique increase the forces experienced by the youth player brain, may make them more susceptible to damage and injury from head impact – potentially making them a more suitable population to trial a heading ban in.

Authors

Ayush Jha

@RonnieJha

5th Year Medical Student, Imperial College London, United Kingdom

Raj Amarnani

@DrRajAmar

Sports & Exercise Medicine Specialist Registrar, The Institute of Sport, Exercise and Health (ISEH), London, United Kingdom

References

(1) Association TF. Statement: Junior football heading. http://www.thefa.com/news/2022/jul/18/statement-heading-trial-u12-games-20221807 [Accessed Mar 21, 2024].

(2) Dementia death more likely in football. BBC Sport. . https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/50124102. [Accessed Mar 21, 2024].

(3) Mackay DF, Russell ER, Stewart K, MacLean JA, Pell JP, Stewart W. Neurodegenerative disease mortality in former professional soccer players. The New England journal of medicine. 2019; 381 (19): 1801-1808. 10.1056/NEJMoa1908483.

(4) Ueda P, Pasternak B, Lim C, Neovius M, Kader M, Forssblad M, et al. Neurodegenerative disease among male elite football (soccer) players in Sweden: a cohort study. The Lancet. Public Health. 2023; 8 (4): e256-e265. 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00027-0.

(5) Russell ER, Mackay DF, Stewart K, MacLean JA, Pell JP, Stewart W. Association of Field Position and Career Length With Risk of Neurodegenerative Disease in Male Former Professional Soccer Players. JAMA neurology. 2021; 78 (9): 1057-1063. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2403.

(6) McKee AC, Alosco M, Huber BR. Repetitive Head Impacts and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2016; 27 (4): 529-535. 10.1016/j.nec.2016.05.009.

(7) McCrory PR. Brain injury and heading in soccer. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2003; 327 (7411): 351-352. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1126775/.

(8) McIntosh AS, Patton DA, Fréchède B, Pierré P, Ferry E, Barthels T. The biomechanics of concussion in unhelmeted football players in Australia: a case-control study. BMJ open. 2014; 4 (5): e005078. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005078.

(9) Naunheim RS, Standeven J, Richter C, Lewis LM. Comparison of impact data in hockey, football, and soccer. The Journal of Trauma. 2000; 48 (5): 938-941. 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00020.

(10) Matser JT, Kessels AG, Lezak MD, Troost J. A dose-response relation of headers and concussions with cognitive impairment in professional soccer players. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2001; 23 (6): 770-774. 10.1076/jcen.23.6.770.1029.

(11) O’Kane JW. Is Heading in Youth Soccer Dangerous Play? The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2016; 44 (2): 190-194. 10.1080/00913847.2016.1149423.

(12) Edwards L. Foam balls and technique training – how Ajax proved children do not need to head the ball. The Telegraph. -11-23 2020. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/football/2020/11/23/foam-balls-technique-training-ajax-proved-children-do-not/. [Accessed Mar 21, 2024].

(13) Neel A. Mastering The Technique of Heading – [Updated]. Play Soccer ball. -09-10T20:00:46+00:00. 2012. https://playsoccerball.wordpress.com/2012/09/10/mastering-the-technique-of-heading/ [Accessed Mar 24, 2024].