Assessing the effects of climate and visitor use on amphibian occupancy in a protected landscape with long-term data

Handling Editor: Andrew M. Kramer

Abstract

Determining where animals are, and if they are persisting across protected landscapes, is necessary to implement appropriate management and conservation actions. For long-lived animals and those with boom-and-bust life histories, perspective across time contributes to discerning temporal trends in occupancy and persistence, and potentially in identifying mechanisms affecting those parameters. Long-term data are particularly useful in protected areas to quantify indicators of change that may be less obvious or occur more slowly. We used long-term amphibian data from Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) in a Bayesian occupancy modeling framework to estimate changes in occupancy, colonization, and persistence of amphibians over three decades and to explore the effects of climate, landscape change, and visitor use as mechanisms behind observed changes. Our results indicate that colonization and persistence are low and/or declining for Pseudacris maculata, Lithobates sylvaticus, and Ambystoma mavortium, and that occupied catchments are increasingly isolated. We found visitor use to have a consistently negative effect on occupancy and persistence of amphibians in RMNP, and that all species are more likely to occupy catchments with more complex habitat and a higher proportion of wetlands. While these results are sobering, they also provide a way forward where mitigation efforts can target identified drivers of change.

INTRODUCTION

Amphibian declines (reported as drastic changes in the number of amphibian populations across a landscape, or population-level extirpations) were recognized as a global concern three decades ago (Wake, 1991) and are now a chronic conservation problem, even in pristine landscapes such as national parks (Halstead et al., 2022). National parks are generally protected from development and resource extraction, and recent evidence supports the value of protected areas, especially for amphibians (Gray et al., 2016; Nowakowski et al., 2023). Despite protection, threats to national parks include drought, wildfires, invasive species, and climate change. These threats are potentially exacerbated by increased visitation resulting in direct impacts on park resources. Climate change is expected to facilitate additional increases in visitation (Fisichelli et al., 2015). The U.S. National Park Service (NPS) has been instrumental in supporting amphibian conservation in the United States by implementing and evaluating conservation measures (Halstead et al., 2022; Ray et al., 2022). For example, amphibians are considered indicators of the condition of natural resources in 54 national parks (Fancy & Bennetts, 2012).

Given the global (Luedtke et al., 2023) and local (Muths et al., 2003; Scherer et al., 2005) concern about amphibian decline, it is useful to identify specific metrics to inform strategies or management actions that facilitate amphibian presence. Useful metrics include an understanding of where amphibians occur in a landscape, how occurrence and persistence may be changing, and what mechanisms might be driving observed changes. Perspective across time can contribute to understanding temporal patterns and mechanisms affecting animal presence and persistence across a landscape. Temporal perspectives are particularly useful in protected areas where mechanisms of change may be less obvious, and species may be declining slowly relative to unprotected areas where development or habitat degradation is clear and species are disappearing rapidly (Maiorano et al., 2008).

Despite the value of such data, long-term data collected with uniform methods that incorporate measures of uncertainty (i.e., detection) are rare. This limitation constrains our ability to estimate the magnitude and direction of change (e.g., change in occupancy, Grant et al., 2020). In some cases, where methodology or implementation is not uniform, newer analytical techniques can accommodate inconsistencies. For example, differences in methods, perceived differences in data reliability, and temporal data gaps can be modeled without compromising the integrity of the resulting inference (Zachmann et al., 2022). Historical data may also be used to supplement, fill gaps, or provide context for the interpretation of modern long-term data (Fisher & Shaffer, 1996; Muths et al., 2016; Skelly et al., 2003). Including all sources of information builds a more complete view of species persistence over time and can facilitate investigations into potential mechanisms of change.

Research has targeted amphibians in Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) since the early 1980s, resulting in a long-term time series of amphibian detection/nondetection data. Coinciding with that effort, visitation has increased (Rocky Mountain National Park, 2023), and visitor use has the potential to be an important mechanism in driving change, especially in protected areas where other types of anthropogenic disturbances (e.g., agriculture, development) are typically minimal relative to nonprotected areas (Larson et al., 2016). Over the course of our study, significant landscape changes (e.g., shift from willow dominated to grass dominated vegetation) affecting hydrology have occurred on the west side of RMNP (Schweiger et al., 2016) which historically had relatively high amphibian diversity compared with other regions of the park (i.e., all extant species, Corn et al., 1997). To explore the effects of these stressors on changes in amphibian occupancy, we developed a Bayesian occupancy model to estimate colonization and persistence probabilities for three time steps over three decades. We identified static (e.g., landscape features) and dynamic (e.g., metrics of climate, landscape change, and visitor use) covariates that we hypothesized could influence amphibian occupancy and quantified their effect. Our study provides a multi-decade perspective on amphibian persistence that can inform conservation decisions that affect amphibians and other wetland obligate species within RMNP. The assessment of potential mechanisms and historical context adds depth to our analysis and allows a more nuanced consideration of conservation strategies for amphibians in this protected landscape.

METHODS

Study site

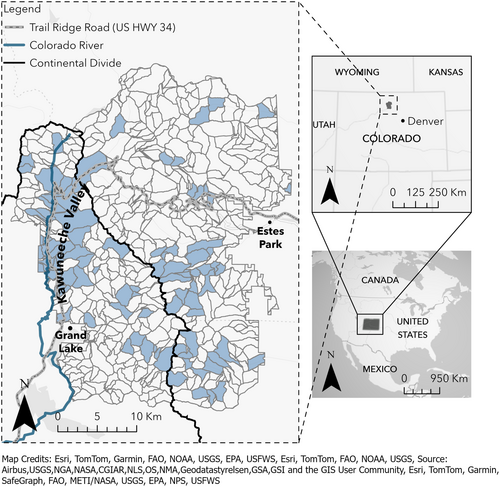

RMNP is a federally protected park in northern Colorado, U.S.A. (Figure 1). This high-elevation (2395–4346 m) protected area is within 105 km of Denver, a major metropolitan city (population ~715,000). Anthropogenic influences, including chemicals such as atrazine (Battaglin et al., 2018) and elevated nitrogen levels (Wolfe et al., 2003), are documented in the park. Rocky Mountain National Park has been among the top 3 most visited national parks in the western United States since 2013 (https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/) and visitation has increased ~60% between 1988 and 2022 (Wesstrom et al., 2021).

Amphibians have been documented in RMNP since the 1930s (Corn et al., 1997). The amphibian fauna is naturally depauperate, including only four species of anurans (boreal chorus frogs, Pseudacris maculata; northern leopard frogs, Lithobates pipiens; wood frogs, Lithobates sylvaticus; boreal toads, Anaxyrus boreas) and one tiger salamander (Ambystoma mavortium) (Hammerson, 1999). Northern leopard frogs have not been seen in RMNP since 1974 despite extensive and intensive surveys (Corn et al., 1997; Muths, unpublished data) and wood frogs occur only in the western portion of RMNP (i.e., west of the Continental Divide). In addition to the extirpation of the northern leopard frog, RMNP has experienced a decline in the number of boreal toad populations—the only toad species in the park—since the mid-1980s (Corn et al., 1997; Muths et al., 2003).

Amphibian detection/nondetection data

We used detection/nondetection data from a database we compiled for three of the four amphibian species currently extant in RMNP (Ambystoma mavortium [AMMA], Lithobates sylvaticus [LISY], and Pseudacris maculata [PSMA]; Kissel & Muths, 2024), from three time periods beginning in the mid-1980s through 2022 (Early, 1988–1994; Mid, 2000–2006; Current, 2020–2022). We chose these time periods because they represent years when park-wide surveys were systematically and consistently conducted. We excluded A. boreas (boreal toads) because they occur at a limited number of known sites in the park and these sites are monitored intensively (e.g., Crockett et al., 2020). Data from the first two time periods were gathered from existing publications (Corn et al., 1997, 2005) and from amphibian surveys and observations in RMNP (Kissel & Muths, 2024). Data collected during the Early time period were collected with a focus on named water bodies consisting of lakes, ponds, and wetlands (henceforth wetlands) and extant amphibian records in RMNP. Two hundred and three wetlands were surveyed 1–15 times each year during May–September (Corn et al., 1997). For many survey locations, only Township, Range, and Section were recorded. We matched these locations with catchments delineated in the early 2000s (Corn et al., 2005, see below). Data during the Mid time period were collected under an occupancy framework (i.e., repeated surveys) at wetlands in a subset of catchments that were derived from the hierarchical Pfafstetter coding system for watersheds (Verdin & Verdin, 1999) to provide spatial representation across the park. The number of catchments targeted in each year varied because of funding and logistical constraints, but broad spatial representation was maintained. Wetlands within each catchment were identified using the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) Database (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2000) to locate potential amphibian breeding habitat (e.g., ponds, ephemeral wetlands). If appropriate wetlands were encountered in the field within a preselected catchment and were not indicated on NWI databases, they were surveyed as well. Wetlands were visited and surveyed at least two times during the active season (i.e., breeding season and larval period, between May and mid-August). Wetlands were surveyed for all life stages of amphibians using double observer, visual encounter protocols, including dipnetting when vegetation or water clarity compromised visibility (Heyer et al., 2014; Nichols et al., 2000). Surveyors listened for calling amphibians before starting surveys.

For data collected during the Early and Mid time periods, we reviewed all records from the amphibian survey database (Kissel & Muths, 2024) for obvious errors in data entry (e.g., incorrect UTMs, dates) and removed or combined duplicate entries. We combined wetlands with the same geographic location regardless of name changes across years, applying the most commonly used name to the record. In cases of wetlands with a UTM location but no datum, we used satellite imagery to locate the most likely site of the wetland and to determine the datum. We converted all location data to NAD27.

To acquire data for the Current time period, which reflects the current status of amphibians in RMNP, we implemented detection/nondetection surveys from 2020 to 2022. Data collection followed the same survey protocols that were implemented in the Mid time period (i.e., double observer visual encounter surveys). To ensure a sufficient sample size for occupancy modeling, we revisited only wetlands that were surveyed in both the Early and Mid periods (Appendix S1: Figure S1).

Covariates

We derived a series of static and dynamic covariates for each catchment. For the first static covariate (Catchment Area), we calculated the area of the Pfaffsteter catchments described above. To calculate the covariate Proportion of Wetlands in each catchment, we acquired spatial data on wetlands across RMNP from the NWI database (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2021). We then summed the total area of wetlands in each catchment and divided it by the catchment area. The third static covariate (Trail Popularity) represented the anthropogenic footprint in the catchment. This covariate was derived from a model that estimates spatially explicit trail use in RMNP (Bredeweg & D'Antonio, 2023). The Bredeweg and D'Antonio model uses a random forest algorithm to predict an ordinally ranked popularity value for trail segments across the park. It was developed using a suite of trail characteristics and an associated training dataset of trails that were categorized by popularity by park experts (Bredeweg & D'Antonio, 2023). Categories for trail popularity were (1) low, (2) medium-low, (3) medium-high and (4) high (Bredeweg & D'Antonio, 2023). We calculated the length of each trail in each of our catchments, then weighted the length of the trail by the popularity category (1–4) from Bredeweg and D'Antonio (2023) and summed the weighted trail lengths for each catchment. We used this value as the static, spatially explicit trail popularity metric in estimating initial occupancy (i.e., occupancy at the Early time period, see below, Table 1).

| Parameter | Covariate | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| ψ1 | Catchment Area | H1: Larger catchments are more likely to be occupied by amphibians |

| Proportion of Wetlands in a Catchment | H2: Catchments with a higher proportion of wetlands are more likely to be occupied by amphibians | |

| Trail Popularity | H3: Catchments with higher trail popularity are less likely to be occupied by amphibians | |

| φ | Catchment Area | H4: Persistence probability will be higher in larger catchments |

| Proportion of Wetlands in a Catchment | H5: Persistence probability will be higher in catchments with a higher proportion of wetlands | |

| Visitor Use | H6: Persistence probability will be lower in catchments with higher visitor use | |

| Precipitation | H7: Persistence probability will be higher in catchments with more precipitation because breeding wetlands are more likely to hold water throughout the active season | |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | H8: Persistence probability will increase as NDVI increases (i.e., higher NDVI values are indicative of more complex habitat such as willows) | |

| γ | Catchment Area | H9: Colonization probability will be higher in larger catchments |

| Proportion of Wetlands in a Catchment | H10: Colonization probability will be higher in catchments with a higher proportion of wetlands | |

| Precipitation | H11: Colonization probability will be higher in catchments with more precipitation because movement corridors are more likely to be wet throughout the active season | |

| NDVI | H12: Colonization probability will increase as NDVI increases (i.e., higher NDVI values are indicative of more complex habitat) |

- Note: Hypotheses are the same for all species: Ambystoma mavortium (tiger salamander), Lithobates sylvaticus (wood frog), and Pseudacris maculata (chorus frog).

We hypothesized that the static covariates would affect our metrics of interest in the following ways: (1) larger catchments are more likely to be occupied initially (i.e., the Early time period), and colonization and persistence are likely to be higher; (2) catchments with a higher proportion of wetlands are more likely to be occupied, and colonization and persistence are likely to be higher; and (3) catchments with higher trail popularity values are less likely to be occupied initially (Table 1). In addition to the volume of traffic on the trail per se, Trail Popularity represents visitor impacts in the catchment. For example, visitors tend to wander from maintained trails (e.g., social trails from campsites to water sources) and human waste products have been documented in the park (Baron et al., 2023; Battaglin et al., 2018). Trails in RMNP often go through or near wetland areas (e.g., the Tonahutu Creek Trail winds through low lying areas with extensive wetlands; the Sprague Lake area includes a partial board walk and is accessible to those with limited mobility; and trails typically end at waterbodies). Additionally, backcountry campsites are frequently located near lakes where campers may use the water and shoreline shallows for drinking, cooking, and washing.

We derived three dynamic covariates: normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), Precipitation, and Visitor Use (Appendix S1: Figure S1). NDVI is a measure of green-up across the landscape and can be a proxy for complexity or change in vegetation because different types of vegetation communities (i.e., grasses vs. shrubs) have different NDVI values (Curran et al., 1983; Sellers, 1985). We used the maximum value of NDVI in August because snow is unlikely to obscure the value, and this month likely represents the peak of the growing season (Hrach et al., 2022). We assumed that the NDVI signal of various plant species at peak growth was most likely to highlight differences in vegetation type across the landscape and across time. We derived NDVI values from LANDSAT satellite imagery (Rouse et al., 1974) in Google Earth Engine (GEE). For each catchment in each year, we extracted the maximum August NDVI and averaged the NDVI values from LANDSAT pixels that fell within the catchment boundary.

Precipitation is important to amphibians in multiple ways, from successful breeding and metamorphosis to survival over winter (Cayuela et al., 2014; Greenberg et al., 2017; Walls et al., 2013). We acquired precipitation data from DAYMET (version 4, Thornton et al., 2022, accessed through GEE) and determined annual cumulative precipitation (henceforth, precipitation) for each catchment for each water year. Precipitation data were available at a 1 km resolution, and NDVI data were available at a 30 m resolution. Our approach focuses on the effects of selected covariates on occupancy across three broad time steps (Appendix S1: Figure S1), in contrast to similar analyses that use covariates to explain changes in (for example) demographic parameters year to year. Thus, to derive the final covariates, NDVI and Precipitation, we averaged the annual values (i.e., maximum August NDVI or annual cumulative precipitation) over the years between Early and Mid and between Mid and Current time periods (Appendix S1: Figure S1).

Finally, we derived a temporally and spatially explicit dynamic metric of visitor use based on the static covariate Trail Popularity (see above). To derive a value for Visitor Use (Table 1), we accessed the annual number of visitors to the park (https://public-nps.opendata.arcgis.com/) and multiplied this value by the static Trail Popularity value. Similar to NDVI and precipitation, we then averaged this product over the years between Early and Mid and between Mid and Current time periods, providing a dynamic and spatially explicit covariate representing the increase in visitor use on trails throughout RMNP. We assumed that spatial patterns in visitor use have not changed through time because basic features of the park have not changed over time, for example, scenic vistas and accessible lakes are the same now as they were 30 years ago. This dynamic covariate represents the potential influence of the number of park visitors and their associated trail use on amphibian persistence.

We hypothesized that the dynamic covariates would affect our metrics of interest in the following ways: (1) persistence and colonization are higher in catchments where Precipitation is higher because precipitation-fed wetlands and streams are expected to stay inundated, or wet, longer, providing adequate habitat through the summer; (2) persistence and colonization probabilities are lower in catchments with lower NDVI values, resulting in less structure/microhabitat and potentially drier soil conditions (Burrow & Maerz, 2022); this is perhaps particularly true on the west side of the park where significant change in the structure and type of vegetation due to over-browsing and changes in hydrology have occurred (Contento et al., 2021; Zeigenfuss & Johnson, 2015); and (3) persistence is lower in catchments where Visitor Use is higher because of expected impacts on habitat or interference with breeding (e.g., direct effects such as egg trampling, or indirect effects such as habitat degradation) (Table 1). We standardized all covariates (dynamic and static) by subtracting the mean and dividing by two SDs (Schielzeth, 2010).

Occupancy model

We derived occupancy histories for our three focal amphibian species (Appendix S1: Figure S1). Because there were discrepancies in wetland locations and names over time, we assigned each site to a Pfafstetter catchment described above and used the catchment as our unit of analysis (Figure 1). For the occupancy analysis, we used only data collected within the three time periods and from catchments that were visited in at least two time periods. Only data for the first three secondary occasions of each year, at each wetland, were included in the analysis. This resulted in 21 possible secondary occasions within a primary occasion (i.e., time period; Appendix S1: Figure S1) for each catchment. To derive catchment-level occupancy histories, we collapsed wetland-specific capture histories within a catchment to a single value for each secondary occasion. For example, if three wetlands were sampled in a single catchment in a year with capture histories 001, 010, and 000 (where 1 indicates a detection and 0 indicates a nondetection) on occasions 1, 2, and 3, respectively, the catchment-level capture history would be 011. This allowed us to leverage all the wetland-specific data to make inference at the catchment scale. We chose to use time periods made up of multiple years as primary occasions and visits within those time periods as secondary occasions because annual turnover in occupancy (i.e., local extinction) for amphibians is low, particularly at broader scales such as catchments (Gould et al., 2012). Structuring the analysis in this way allowed us to evaluate persistence and colonization probabilities over time scales at which they likely occur for amphibians (i.e., multiple years).

We fitted the model in JAGS (Plummer, 2003) using the wrapper “jagsUI” (Kellner, 2019) for the statistical programming language R (R Core Team, 2018). We ran three chains with 1,000,000 iterations each, a burn-in of 600,000 and a thinning rate of 50, for a total of 24,000 iterations. We checked for model convergence by calculating the Gelman–Rubin convergence diagnostic () for each parameter and used values <1.1 as our criterion for convergence (Gelman & Rubin, 1992). Additionally, we examined the posteriors of the coefficients for sufficient mixing and report the effective sample size for each parameter. We used the model to make spatially explicit predictions of occupancy for each species, catchment, and time period.

RESULTS

Detection/nondetection surveys for amphibians were conducted by field crews at 217 unique wetlands across RMNP from 2020 to 2022. In 2020, 21 wetlands were surveyed between 9 June and 31 July. Efforts were limited because of COVID-19 restrictions on fieldwork imposed by NPS and USGS. In 2021, crews surveyed 121 wetlands between 7 June and 20 August. This effort was limited because of restricted access related to the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires that caused significant damage to park landscapes and infrastructure (https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/fire-history.htm). In 2022, 168 wetlands were surveyed between 18 May and 22 August.

These data were added to the data from the two earlier time periods, resulting in a comprehensive amphibian observation database for RMNP containing 4886 survey records (Kissel & Muths, 2024). Of these, 1360 surveys represented wetlands that met our criteria of (1) falling within one of the 96 defined catchments (Figure 1) and (2) having been visited in at least two of our three defined time periods. These data were used to model occupancy, colonization, persistence, and detection probabilities and test hypotheses (Table 1) about the effect of covariates on these parameters. For each of our modeled parameters (probability of initial occupancy, persistence probability, colonization probability), we report the mean coefficient estimates and the cumulative probability that the coefficient estimate has a negative or positive effect on the demographic parameter from the posterior distribution (Table 3). We present the cumulative probability of the sign of the coefficient (positive or negative) because it allows us to leverage the full posterior distribution(s) from the model to provide additional inference regarding the effect of the covariate on the parameter estimate beyond a single point (e.g., mean value) estimate (Hobbs & Hooten, 2015).

Occupancy

Because the number of catchments visited varied in each time period, we report the proportion of catchments where species were present (i.e., naïve occupancy) for each time period, in addition to the total number of observations for each amphibian species (Table 2). Overall, the proportion of catchments with observations of any species was relatively low (<0.35). The proportion of catchments with PSMA observations was highest in the Current time period, and PSMA were observed in just over one third of catchments surveyed (Table 2). The proportion of catchments where LISY were observed was highest in the Mid time period (0.13) compared with 0.07 and 0.06 in the Early and Current time periods. The proportion of catchments where AMMA were observed was similar across time periods and ranged from 0.06 in the Mid time period to 0.09 in the Current time period (Table 2).

| Time period | Total no. catchments | PSMA | LISY | AMMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | 85 | 0.29 (61) | 0.07 (8) | 0.08 (13) |

| Mid | 94 | 0.26 (52) | 0.13 (18) | 0.06 (11) |

| Current | 80 | 0.34 (65) | 0.09 (9) | 0.09 (14) |

- Note: The total number of observations for each species in each time period is indicated in parentheses. Early, 1988–1994 (7 years); Mid, 2000–2005 (6 years); Current, 2020–2022 (3 years).

- Abbreviations: AMMA, Ambystoma mavortium (tiger salamander); LISY, Lithobates sylvaticus (wood frog); PSMA, Pseudacris maculata (chorus frog).

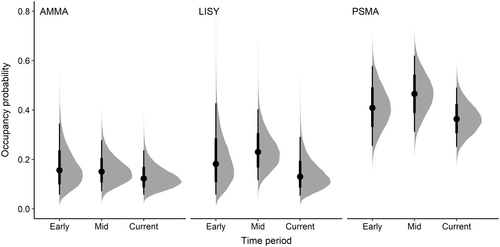

Model results indicated that the probability of occupancy was lowest in the Current time period (2020–2022) for all three species (Figure 2; Appendix S1: Figure S2). PSMA had the highest probability of occupancy in all time periods ranging from a mean probability of 0.47 (95% credible interval [CI] = 0.31–0.62) in the Mid time period, to 0.37 (CI = 0.25–0.49) in Current time period. The probability of occupancy for AMMA declined from a mean probability of 0.17 (CI = 0.06–0.35) in the Early time period, to 0.13 (CI = 0.07–0.24) in the Current time period. The probability of occupancy for LISY followed a pattern similar to PSMA, with the mean probability highest in the Mid time period (mean = 0.24, CI = 0.12–0.40), and lowest in the Current time period (mean = 0.14, CI = 0.05–0.29) (Figure 2). The mean occupancy values for each time period and species, along with values (all of which were <1.1) and effective sample sizes are reported in Appendix S1: Table S1.

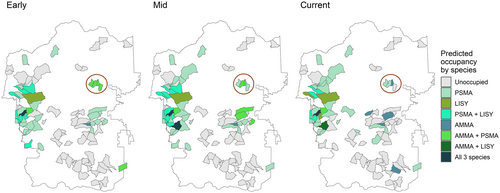

Park-wide (across the 96 sampled catchments), model results indicated that 41 (CI = 29–94), 48 (CI = 25–92), and 44 (CI = 34–86) catchments were occupied by one or more amphibian species in the three time periods, respectively (Figure 3). The distribution of occupied catchments across the landscape varied over time but was generally highest on the west side of the park (i.e., in and around the Kawuneeche Valley, Figure 1). The Kawuneeche Valley is the only area in RMNP that contained catchments predicted to be occupied by all three species of our target species: one catchment in the Early and Current time periods and in two catchments in the Mid time period (Figure 3).

We modeled the initial probability of occupancy (i.e., occupancy in the Early time period, ψ1) as a function of three covariates: Catchment Area, Proportion of Wetlands, and Trail Popularity (Table 1). The mean coefficient estimate for Catchment Area was negative for all three species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3a–c), and the cumulative probability that Catchment Area had a negative effect on initial occupancy was ≥0.68 for all species (Table 3). The mean coefficient estimates for the Proportion of Wetlands were positive for all three species (Appendix S1: Figure S3a–c), and the cumulative probability that the Proportion of Wetlands had a positive effect on initial occupancy was ≥0.54 for all species (Table 3). Finally, the mean coefficient estimate for Trail Popularity for all three species was negative (Appendix S1: Figure S3a–c) and the cumulative probability that the coefficient estimate for Trail Popularity had a negative effect on initial occupancy was ≥0.60 for all three species (Table 3).

| Parameter | Species | Hypothesis | Mean | LCI | UCI | Cumulative probability | Hypothesis supported? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||||||

| ψ1 | AMMA | H1: Catchment Size | −0.27 | −1.59 | 0.93 | 0.32 | 0.68 | N |

| H2: Prop. Wetlands | 0.12 | −1.34 | 1.59 | 0.58 | 0.42 | Y | ||

| H3: Trail Popularity | −0.26 | −2.12 | 1.57 | 0.38 | 0.62 | Y | ||

| LISY | H1: Catchment Size | −0.27 | −1.64 | 1.07 | 0.32 | 0.68 | N | |

| H2: Prop. Wetlands | 0.33 | −1.49 | 4.08 | 0.58 | 0.42 | Y | ||

| H3: Trail Popularity | −0.18 | −2.01 | 1.88 | 0.40 | 0.60 | Y | ||

| PSMA | H1: Catchment Size | −0.34 | −1.36 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.75 | N | |

| H2: Prop. Wetlands | 0.10 | −1.10 | 1.61 | 0.54 | 0.46 | Y | ||

| H3: Trail Popularity | −0.50 | −1.96 | 0.84 | 0.23 | 0.77 | Y | ||

| φ | AMMA | H4: Catchment Size | −2.33 | −10.92 | 2.39 | 0.23 | 0.77 | N |

| H5: Prop. Wetlands | 2.66 | −8.82 | 13.29 | 0.71 | 0.29 | Y | ||

| H6: Visitor Use | −6.76 | −24.41 | 11.48 | 0.23 | 0.77 | Y | ||

| H7: Precipitation | −6.26 | −18.16 | 2.44 | 0.09 | 0.91 | N | ||

| H8: NDVI | 2.65 | −3.61 | 10.90 | 0.78 | 0.22 | Y | ||

| LISY | H4: Catchment Size | −0.29 | −5.21 | 4.66 | 0.44 | 0.56 | N | |

| H5: Prop. Wetlands | 2.38 | −7.87 | 13.18 | 0.66 | 0.34 | Y | ||

| H6: Visitor Use | −6.14 | −23.99 | 12.69 | 0.25 | 0.75 | Y | ||

| H7: Precipitation | −5.00 | −16.59 | 3.91 | 0.15 | 0.85 | N | ||

| H8: NDVI | 3.25 | −2.65 | 11.90 | 0.84 | 0.16 | Y | ||

| PSMA | H4: Catchment Size | 0.29 | −1.16 | 1.96 | 0.64 | 0.36 | Y | |

| H5: Prop. Wetlands | 4.31 | 0.09 | 11.01 | 0.98 | 0.02 | Y | ||

| H6: Visitor Use | −6.90 | −24.36 | 11.13 | 0.22 | 0.78 | Y | ||

| H7: Precipitation | 3.23 | −0.45 | 8.01 | 0.96 | 0.04 | Y | ||

| H8: NDVI | 2.33 | −2.13 | 7.80 | 0.82 | 0.18 | Y | ||

| γ | AMMA | H9: Catchment Size | 0.43 | −1.96 | 3.33 | 0.64 | 0.36 | Y |

| H10: Prop. Wetlands | −0.16 | −4.85 | 2.96 | 0.54 | 0.46 | Y | ||

| H11: Precipitation | 0.37 | −2.54 | 2.77 | 0.65 | 0.35 | Y | ||

| H12: NDVI | 0.72 | −2.18 | 3.85 | 0.69 | 0.31 | Y | ||

| LISY | H9: Catchment Size | −0.54 | −4.83 | 2.30 | 0.41 | 0.59 | N | |

| H10: Prop. Wetlands | 0.42 | −4.63 | 5.86 | 0.59 | 0.41 | Y | ||

| H11: Precipitation | 0.80 | −2.61 | 3.85 | 0.73 | 0.27 | Y | ||

| H12: NDVI | 0.60 | −3.22 | 4.23 | 0.65 | 0.35 | Y | ||

| PSMA | H9: Catchment Size | 1.44 | −0.12 | 3.45 | 0.97 | 0.03 | Y | |

| H10: Prop. Wetlands | 1.12 | −3.38 | 4.76 | 0.82 | 0.18 | Y | ||

| H11: Precipitation | 0.82 | −2.46 | 3.92 | 0.73 | 0.27 | Y | ||

| H12: NDVI | 0.19 | −3.80 | 3.67 | 0.57 | 0.43 | Y | ||

- Note: Parameter estimates are on the logit scale. Values in boldface signify whether the bulk of the probability (i.e., >0.50) indicated a positive or negative effect of the covariate on the parameter.

- Abbreviations: AMMA, Ambystoma mavortium (tiger salamander); LISY, Lithobates sylvaticus (wood frog); NDVI, normalized difference vegetation index; Prop., proportion; PSMA, Pseudacris maculata (chorus frog).

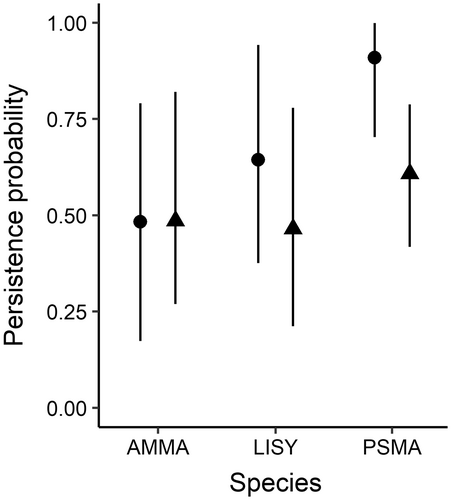

Persistence

Persistence probability (the probability that an occupied catchment remained occupied between two time periods) was higher from the Early to the Mid time period for PSMA and LISY (mean = 0.91, CI = 0.70–0.99; mean = 0.64, CI = 0.38–0.94, respectively) than from the Mid to the Current time period (mean = 0.61, CI = 0.42–0.79, mean = 0.47, CI = 0.21–0.78, for PSMA and LISY respectively) (Figure 4; Appendix S1: Table S1). Persistence probability for AMMA was indistinguishable between the Early and Mid time periods and between the Mid and Current time periods (mean = 0.48, CI = 0.17–0.79; mean = 0.49, CI = 0.27–0.82, respectively; Appendix S1: Table S1).

The mean coefficient estimates for the effect of Precipitation on persistence probability were negative for AMMA and LISY but positive for PSMA (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3d–f). The cumulative probability that Precipitation had a negative effect on persistence was 0.91 and 0.85 for LISY and AMMA, respectively, while the cumulative probability that Precipitation had a positive effect on persistence was 0.73 for PSMA (Table 3). The mean coefficient estimate for the effect of NDVI on persistence probability was positive for all three species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3d–f), and the cumulative probability that NDVI had a positive effect on persistence was ≥0.78 for all three species (Table 3). The mean coefficient estimate for the effect of Visitor Use was negative for all three species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3d–f), and the cumulative probability that Visitor Use had a negative effect on persistence was ≥0.75 for all three species (Table 3).

The mean coefficient estimate for the effect of Catchment Area on persistence for PSMA was positive, but the mean coefficient estimates for AMMA and LISY were negative (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3d–f). The cumulative probability that Catchment Area had a positive effect on persistence probability for PSMA was 0.64, whereas the cumulative probability that Catchment Area had a negative effect for AMMA and LISY was 0.77 and 0.56, respectively (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3d–f). The mean coefficient estimate for the effect of the Proportion of Wetland area within a catchment on persistence probability was positive for all three species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3d–f) and the cumulative probability that the Proportion of Wetlands in a catchment had a positive effect was ≥0.66 for all three species (Table 3).

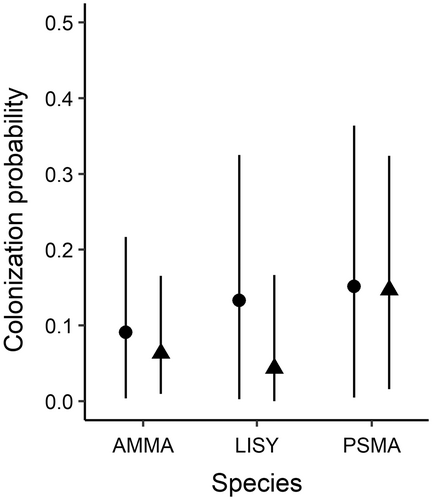

Colonization

Colonization probability (the probability that an unoccupied catchment became occupied between two time periods) was relatively low for all species (Figure 5; Appendix S1: Table S1). Colonization probability was highest for PSMA and was the same from Early to Mid time periods and Mid to Current time periods (mean = 0.15, CI = 0.01–0.36; mean = 0.15, CI = 0.02–0.32, respectively). Colonization probability was lower for LISY and AMMA. For LISY, the mean probability of colonization from the Early to Mid time period was 0.13 (CI = 0.002–0.32) and from the Mid to Current time period was 0.04 (CI = 0.001–0.17). For AMMA, the mean probability of colonization was 0.09 (CI = 0.004–0.22) from the Early to Mid time period and 0.06 (CI = 0.01–0.17) from the Mid to Current time period (Appendix S1: Table S1).

The mean coefficient estimate for the effect of Precipitation on colonization probability was positive for all three species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3g–i). The cumulative probability that the sign of the coefficient for the effect of Precipitation on colonization probability was positive was ≥0.65 for AMMA, LISY, and PSMA (Table 3). The mean coefficient estimate for the effect of NDVI on colonization probability was also positive for all three species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3g–i). The cumulative probability that the sign of the coefficient was positive for the effect of NDVI on colonization was ≥0.57 for all three species (Table 3). The mean coefficient estimate for the effect of Catchment Area on colonization probability was positive for AMMA and PSMA, but negative for LISY. The cumulative probability that the sign of the coefficient for the effect of Catchment Area was positive for AMMA and PSMA was 0.64 and 0.97, respectively, and the cumulative probability that the sign of the coefficient was negative for LISY was 0.59 (Table 3). Finally, the mean estimate for the effect of the Proportion of Wetlands on colonization probability was positive for LISY and PSMA. For AMMA, while the mean estimate for the effect of the Proportion of Wetlands was negative (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3g–i) the cumulative probability that the sign of the coefficient was positive was 0.54. The cumulative probability that the sign of the coefficient was positive for the effect of the Proportion of Wetlands on the probability of colonization for LISY and PSMA was 0.59 and 0.82, respectively (Table 3).

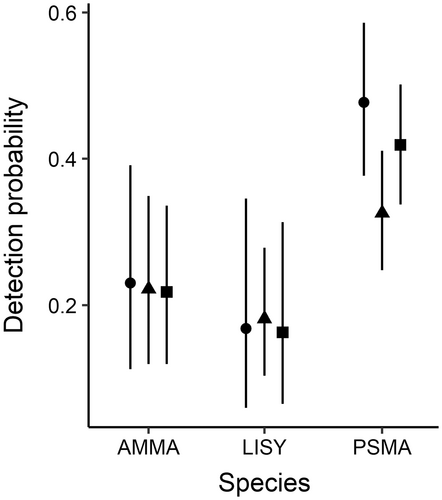

Detection probability

Detection probability was highest for PSMA (range 0.33–0.48), followed by AMMA (~0.22 for all three time periods) and LISY (range 0.16–0.18) and did not change significantly over the Early, Mid, and Current time periods (Figure 6; Appendix S1: Table S1).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis signals that the probability of occupancy for three amphibian species in RMNP is declining. Specifically, our data reveal reduced occupancy at multiple catchments by one or more species in the Current time period. This decadal perspective shows that although occupancy appeared to increase at the midpoint of data collection for two species, the probability of occupancy for all three species is lowest in the Current time period. While there is a considerable amount of uncertainty in our estimates for all species (i.e., overlapping credible intervals; Figure 2), there are consistent patterns across species and covariates. These data serve as an early indicator of probable further declines in amphibian occupancy in RMNP. Northern leopard frogs are presumed extirpated since the 1970s (Corn et al., 1997; Corn & Fogleman, 1984), and boreal toads (the only bufonid [toad] in the park) have declined dramatically (Corn et al., 1997; Muths et al., 2003; Scherer et al., 2008) The extirpation, decline, or suggested decline (this study) in 100% of amphibians (5 of 5 species) across the park is concerning.

Fewer catchments were occupied by one or more of the three species in the Current time period, and connectivity has been lost among catchments (Figure 3; Appendix S1: Figure S2). Loss of connectivity (i.e., increased distance or higher difficulty in navigating even a short distance) can affect migration and population genetics (Scherer et al., 2012; Watts et al., 2015), and thus persistence. P. maculata had the highest probability of occupancy of the three species that we assessed and is the most widely distributed amphibian species in RMNP. Occupancy for PSMA increased slightly during the Mid time period but declined in the Current time period. Occupancy for LISY, a species confined to the west side of the park, mirrored PSMA, with a slight increase in the Mid time period but lower occupancy in the current time period. For AMMA, occupancy declined over all time periods (Figure 2).

Changes in individual species occupancy can drive the frequency of co-occurrence of species within a catchment. There are few locations in the park where all three species occur together, and co-occurrence by two species in a catchment is more common, but not widespread (Figure 3). For example, in the Early time period, AMMA and PSMA were predicted to occupy small adjacent catchments in the northeast part of the park. In the Mid time period, both were predicted to occupy only two of these catchments, and in the Current time period, only three of the four catchments were predicted to be occupied at all, two by PSMA alone and one by AMMA alone, illustrating a general decline in amphibian occupancy for this area of the park (Figure 3, red circles). While this is likely not the result of biological interactions (e.g., competition) among these species, it is of interest to managers who value sites where there is full representation of extant species. Such data may also aid in developing more nuanced studies to ask questions about why particular species no longer occur at these wetlands.

We assessed the effects of several covariates that we hypothesized would affect occupancy, persistence, and colonization. In addition to reporting the mean coefficient estimate and 95% credible interval for each covariate, we calculated the cumulative probability, from their posterior distributions, that the covariate had a positive or negative effect on the associated parameter (initial occupancy probability, persistence probability, and colonization probability). This information provides insight into potential mechanisms behind observed patterns. By using the full Bayesian posterior of the covariate (Ellison, 2004; Hobbs & Hooten, 2015), our analysis allowed us to quantify the likelihood of a covariate (e.g., Trail Popularity) affecting a target parameter (e.g., persistence) either positively or negatively.

For the probability of initial occupancy (i.e., occupancy in the Early time period), the effects of covariates (Proportion of Wetlands, Trail Popularity) were similar across all three species (Table 3). For the covariate Proportion of Wetlands, the cumulative probability from the posterior distribution indicated a positive effect on initial occupancy for all species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3). This suggests that catchments with a higher proportion of wetlands are more likely to be occupied and supports our hypothesis. More wetlands provide more suitable habitat, increasing the probability of occupancy (sensu stepping-stone network; Watts et al., 2015). For the covariate Trail Popularity (static covariate of spatially explicit trail use by visitors), the cumulative probability from the posterior distribution indicated a negative effect on initial occupancy for all three species (Table 3, Appendix S1: Figure S3). This suggests that catchments with more trails, or trails that are more heavily used, were less likely to be occupied by amphibians in the Early time period relative to catchments with fewer trails, or trails that are less heavily used. Both the Proportion of Wetlands in a catchment and Trail Popularity are features that can theoretically be manipulated by managers via wetland construction/restoration and/or regulations to manage visitors in sensitive areas.

For the covariates Proportion of Wetlands and NDVI, the cumulative probabilities from the posterior distributions indicated positive effects on persistence and colonization (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3) for all three species. This suggests that a higher proportion of wetlands and greater vegetation complexity (i.e., higher NDVI values) increased persistence and colonization, which supports our hypotheses. A higher proportion of wetlands in a catchment and higher NDVI values (indicating a more shrub-/tree-dominated vegetation community) likely facilitate movement and colonization, as well as provide microhabitat for terrestrial individuals. For example, more wetlands within a catchment and a landscape with more complex habitat (i.e., willows vs. grass dominated) allow individuals to move shorter distances to the next patch of suitable habitat and minimize predation and desiccation risk (Burrow & Maerz, 2022; Lertzman-Lepofsky et al., 2020; Zamberletti et al., 2018).

For the covariate Visitor Use, the cumulative probability from the posterior distribution indicated a negative effect on persistence for all three species (Table 3; Appendix S1: Figure S3) (we did not include it as a covariate for colonization). This suggests that as Visitor Use increases, the probability of persistence of amphibians decreases, which supports our hypothesis and aligns with our results indicating a negative effect of Trail Popularity on initial occupancy.

The direction of the effect of Precipitation on persistence is somewhat counterintuitive; results indicated the increased precipitation was negatively associated with persistence for LISY and AMMA, contrary to our hypothesis. However, too much precipitation can increase water levels, inundating breeding shallows and affecting successful egg laying. Increased depth decreases temperature, which can limit growth and potentially delay metamorphosis and reduce metamorph survival, thus affecting recruitment and persistence. Breeding occurs slightly earlier in LISY (than in PSMA) which could exacerbate the effects of Precipitation. For colonization probability, there was a positive effect of Precipitation for all three species, which aligns with our hypothesis that catchments with more precipitation are likely to be “wetter” across the active season and may provide low-cost movement corridors that facilitate dispersal and colonization from one site to another (Bartelt et al., 2022).

Several patterns emerged across parameters and covariates in our analysis. For example, the Proportion of Wetlands in a catchment had a positive effect on initial occupancy, persistence, and colonization. Given that wetlands in RMNP are driven by precipitation in the form of snow (Mote et al., 2005), drought is likely to affect the Proportion of Wetlands in catchments, and subsequently, amphibian occupancy. Additionally, we found that higher NDVI values were associated with increased initial occupancy, persistence, and colonization. NDVI is a proxy for vegetation complexity (Curran et al., 1983; Sellers, 1985), which can be linked to soil moisture (D'Odorico et al., 2007) and logically to drought. While there were periods of “moderate” drought in Rocky Mountain National Park between the Early and Mid time periods, there were more frequent and more intense (i.e., “extreme”) droughts between the Mid and Current time periods (Hegewisch & Abatzoglou, 2024).

Drought is an important factor in amphibian recruitment, persistence, and dispersal, and is relevant for common species (i.e., PSMA) and for species that inhabit relatively small areas in the park (i.e., LISY). Drought has been shown to negatively affect AMMA (Wissinger & Whiteman, 1992), which are also more likely to be susceptible to water loss than other amphibians in RMNP (Toledo & Jared, 1993). The effects of drought, including reduced hydroperiods and vegetation complexity and lower snowpacks, can affect survival in anuran amphibians (Amburgey et al., 2012; Burrow & Maerz, 2022; Crockett et al., 2020; Kissel et al., 2019; Muths et al., 2016, 2017, 2020).

Drought, in the form of reduced hydroperiods, can affect the incidence and transmission of diseases such as chytridiomycosis and ranaviruses (Adams et al., 2017; Muths & Hossack, 2022; Rollins-Smith, 2017; Tompkins et al., 2015). Chytridiomycosis occurs in boreal toads in RMNP (Muths et al., 2003) and has been detected in PSMA and LISY (Rittman et al., 2003). Ranaviruses are not known to occur in RMNP (Green & Muths, 2005) but are present in similar systems in the nearby Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) and are widespread in the western United States (Muths & Hossack, 2022). Ranaviruses have been linked to amphibian death in the GYE (Patla et al., 2016) and to population-level effects on amphibians in the eastern United States (Earl & Gray, 2014).

Our results indicate that Trail Popularity and Visitor Use have a negative effect on initial occupancy and persistence, respectively. While other studies have anecdotally linked increases in visitor use to amphibian declines in national parks (e.g., Yellowstone National Park, Patla & Peterson, 2022), our study is one of the few that we are aware of that has quantitatively explored the effects of increasing visitor use in a protected landscape on the persistence of amphibians over time (Larson et al., 2016; but see Rodríguez-Prieto & Fernández-Juricic, 2005). While the mechanisms (e.g., habitat trampling and alteration, increased contaminants, increased spread of disease) driving this result cannot be elucidated from this study, these data provide baseline information to park managers. Together, these findings emphasize the importance of further research into the potential impacts of visitors on amphibians. Popular trails in RMNP are often associated with lakes and ponds (e.g., Bear Lake), and thus overlap between park visitors and amphibian habitat is likely. Notably, the decrease in persistence probability from the Mid to Current time periods coincides with a record increase in visitors from 2010 to 2019 (Rocky Mountain National Park, 2023), which has prompted changes in visitor access (e.g., timed entry, Rocky Mountain National Park, 2023).

Unlike the abiotic covariates that we tested (e.g., Catchment Size, Precipitation), there is the potential for managers to investigate and mitigate impacts from visitors, as well as manipulate the proportion of wetlands in a catchment and manage habitat in a way that increases NDVI (i.e., habitat complexity) on the landscape. Our spatially explicit analysis provides insight into areas within the park that may benefit from such management actions (i.e., catchments where occupancy has declined).

National parks and other protected areas are keystones of conservation. While protected areas are likely more resilient to landscape-level anthropogenic change than unprotected areas (Nowakowski et al., 2023), anthropogenic impacts related to visitation are of concern, and climate-induced landscape changes (e.g., vegetation shifts, fire) are gaining attention from managers (Schuurman et al., 2022). For example, in 2020, the East Troublesome Fire affected much of RMNP, including the Kawuneeche Valley. This fire occurred between our Mid and Current time periods and may have contributed to observed declines in occupancy, but we lack data to test this directly.

We capitalized on long-term data to investigate changes in amphibian occupancy that might not be apparent over short (i.e., a few years) time scales. Based on a 30-year time series of occupancy data, our results indicate that the outlook for amphibian persistence in RMNP may not be secure. Specifically, for the 3 species that we assessed, colonization and persistence are low and/or declining. Persistence across a landscape is an important metric, perhaps more useful than population abundance because it is better suited to large-scale monitoring projects (i.e., detection/nondetection data are less resource-intensive to collect than indices of abundance). If the occupancy of the remaining species of amphibians in RMNP continues to wane, increased spatial isolation may further decrease the probability of colonization, potentially leading to loss of genetic diversity and increasing vulnerability to human disturbance (e.g., Visitor Use) and catastrophic events like fire, thus negatively affecting persistence.

However, by exploring mechanisms (i.e., NDVI, habitat complexity; Proportion of Wetlands, habitat availability; and Visitor Use) that are potentially driving occupancy patterns, we provide an opportunity to develop proactive mitigation strategies. Despite uncertainty in our results (i.e., highly overlapping credible intervals), the general patterns are useful indicators for a system in which even small perturbations can lead to significant changes in the extant amphibian fauna (e.g., if LISY is lost, there would be no more ranid frogs in RMNP). Particularly in the context of the lost (northern leopard frogs) and declining (boreal toads) amphibian species in RMNP, these results illustrate the importance of continued monitoring and the identification of management actions. Such management actions might be designed to ameliorate negative effects of identifiable factors affecting occupancy or persistence, or factors that are expected to be exacerbated by climate change, such as drought.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff at Rocky Mountain National Park, particularly the backcountry office and S. Esser. P.S. Corn initiated this project in the 1980s, and we appreciate this early work. We also thank A. Wray and B. Halstead for reviewing and providing input on the manuscript, and E. Dietrich for assisting with Figure 1. We are grateful to the many technicians who have assisted in collecting these data. This work was partially funded by a grant from the Continental Divide Research Learning Center to A. Kissel and E. Muths. This manuscript is contribution number 896 of the USGS Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative (ARMI). Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available from the USGS Science Base Catalog: https://bibliotheek.ehb.be:2102/10.5066/P9EX70L7.