Wayfinding, knowledge, perspective, and engagement: Preparing tribal liaisons for stewardship of Indigenous lands

Handling Editor: Jennifer L. Momsen

Abstract

Indigenous stewardship practices, deeply rooted in traditional values and knowledge, often differ from non-Indigenous management approaches. Bridging these differing practices and approaches requires professionals trained in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures, knowledge, and practices. The Environmental Stewardship of Indigenous Lands (ESIL) certificate at the University of Colorado Denver aims to prepare students for such roles, particularly as tribal liaisons, who facilitate government-to-government relationships and consultations. In particular, the ESIL certificate combines academic coursework with workshops and internships that provide knowledge and skills critical for effective liaison work, such as understanding tribal governance, communication, conflict resolution, and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). The motivation for this work is that the preparation of tribal liaisons in higher education institutions faces several challenges such as rigid disciplinary curricula and insufficient access to culturally relevant immersive experiences in Indigenous communities and organizations. ESIL addresses these challenges through its workshops and internships, which complement traditional coursework by providing culturally relevant learning opportunities. Workshops cover topics like tribal law, TEK, and Indigeneity, while internships offer hands-on experiences that bridge academic learning with real-world contexts and applications. This paper presents the experiences in creating and operating workshops and internships as part of the ESIL certificate program. Workshops and internships were created following the theory of culturally relevant pedagogy, and student feedback was collected following the Indigenous evaluation framework. Student feedback indicates that these activities complement students' education and training to become effective tribal liaisons by enhancing their wayfinding, knowledge acquisition, perspective taking, and engagement with Indigenous cultures, knowledge, and practice. The ESIL program's approach underscores the importance of culturally tailored education and strong partnerships with Indigenous professionals and communities to prepare the next generation of tribal liaisons.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, including Alaska Native Corporations (US Bureau of Indian Affairs, 2024a), and designated tribal lands comprise approximately 24 million ha (60 million acres) in the contiguous 48 states alone (Riley, 2017). Tribes, government (federal, state, and local), and nonprofit organizations have a responsibility for the stewardship of these lands. Among these, tribes have the longest tradition of land stewardship (Flores & Russell, 2020), rooted in time-tested practices, values, culture, epistemologies, and ontologies (Anderson, 2005; Bengston, 2004; Hoagland, 2017; Huntington, 2000). Non-tribal governments and organizations often have management principles and practices that differ from their Indigenous counterparts. Indeed, this difference is reflected in the deliberate choice of the words stewardship or management in the preceding sentences. The non-tribal management of lands and natural resources is immersed in sets of laws, regulations, and policies that frequently differ between tribal and non-tribal areas of jurisdiction and control (e.g., Flanders, 1998; Krakoff, 2013). Furthermore, they also might differ at different geographical and institutional scales (e.g., tribal vs. federal vs. state vs. local). These differences, among others, create complex contexts and worldviews that must be bridged to arrive at agreements that allow the achievement of shared goals and objectives (Murry et al., 2013; Schelhas, 2002). Given this situation, there is a pressing need for professionals who are educated and trained in the culture, practice, knowledge, and skills that would allow them to provide significant contributions to bridging the tribal and non-tribal contexts and worldviews for the stewardship of Indigenous lands (Brooks, 2022). One professional position that is tasked with such a role is a tribal liaison, a position whose formal name under the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs is tribal liaison officer (US Bureau of Indian Affairs, 2024b).

The Environmental Stewardship of Indigenous Lands (ESIL) certificate at the University of Colorado Denver (CU Denver, 2024a) aims to prepare students to fulfill the role of tribal liaison in tribal, government, and nongovernmental organizations. The certificate comprises regular academic courses, mentorship, workshops, and internships. Given the nature, breadth, and depth of the knowledge and skills required to be an effective tribal liaison, workshops and internships play an important role in the refinement and expertise of informed, highly knowledgeable students and in the achievement of ESIL's mission “to broaden participation of students in STEM through education and community partnerships that promote healing and stewardship of Native land” (CU Denver, 2024b). In previous work, we reported the backgrounds, experiences, and outcomes of students participating in the ESIL program (Mays et al., 2025). Here, we present new qualitative data (i.e., student reflections) specifically focused on the creation and operation of a series of workshops and internships aimed at complementing regular academic courses required for obtaining the ESIL certificate at CU Denver.

This paper is structured as follows. In the Introduction, we present the responsibilities and traits that a tribal liaison should possess, summarize the challenges that institutions of higher education face to effectively provide the education and training required by a tribal liaison, summarize the benefits of extracurricular learning, and describe how the ESIL certificate is structured and operated to provide students with knowledge and skills. In the following section, we present our experiences in conducting two types of extracurricular learning that are integral to the ESIL certificate: workshops and internships. The Results section summarizes key findings that emerged from the assessment of these activities, while the Discussion section places our results into a theoretical context and highlights a few particularly salient points. The final section presents conclusions and recommendations based on our experiences.

Roles, responsibilities, and traits of tribal liaisons

A tribal liaison is a person (or group of people) designated by their organization to carry out the responsibilities outlined in the organization's tribal consultation policy. Tribal liaisons work to strengthen the government-to-government relationships with tribes throughout the United States (US Bureau of Indian Affairs, 2024b). A tribal consultation is a formal, two-way, government-to-government dialogue between official representatives of tribes and federal, state, or local governments or nongovernmental agencies to discuss proposals before making decisions (Hanschu, 2014; Metropolitan Council, 2024; US Bureau of Indian Affairs, 2024c). Each organization has a more detailed description of the roles and responsibilities of their tribal liaison (e.g., US Air Force, 2020; US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2021). In general, these responsibilities include the ones listed in Box 1.

BOX 1. Roles and responsibilities of tribal liaisons (US Air Force, 2020; US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2021)

- Promotion of trust and responsibility.

- Commitment to a government-to-government relationships and partnerships.

- Responsibility to conduct outreach and engagement.

- Obligation for timely consultation.

- Coordination with other federal, state, or local agencies for joint tribal consultation.

- Engagement of state-recognized tribes in decision-making.

- Advocate for tribal priorities and concerns.

- Provide and promote cultural awareness, sensitivity, and responsiveness.

- Advise and provide guidance for decision-making, policies, initiatives, or projects.

- Consultation and conflict resolution.

- Capacity building by facilitating culturally relevant, sensitive, and responsive access to resources, education, training, or other forms of support that the tribal or non-tribal agency can provide.

To embody these roles and uphold these responsibilities, tribal liaisons require a portfolio of knowledge and skills; the desirable knowledge and skills of an effective tribal liaison are numerous and profound. Their description varies by organization and context. The ones presented in Box 2 are noted by several organizations (e.g., Francis-Begay, 2013; King County, 2017). Furthermore, the knowledge and skills listed in Box 2 were also highlighted by the ESIL external Indigenous partners who work as tribal liaisons in various contexts and organizations.

BOX 2. Desirable knowledge and skills of a tribal liaison (Francis-Begay, 2013; King County, 2017)

- Knowledge of tribal and non-tribal laws and regulations, including preeminence.

- Knowledge of the socio-cultural, legal, political, economic, and environmental history and current state of Native American nations and Indigenous lands.

- Knowledge of cultural sensitivity and responsiveness and how to address and implement them.

- Knowledge of tribal governance and decision-making processes.

- Knowledge of Indigenous communication (oral, written, visual) and cultural engagement.

- Knowledge of Indigenous participatory decision-making, as well as Indigenous and non-Indigenous conflict resolution.

- Knowledge of Indigenous and non-Indigenous strategic planning approaches.

- Ability to bridge, in culturally relevant ways, the tribal and non-tribal contexts and worldviews, ensuring that both sides are informed about each other's needs, concerns, priorities, and views.

- Ability to communicate and explain complex cultural, technical, and legal concepts and materials in oral, written, and visual ways to people of diverse cultural backgrounds, education levels, and language skills.

- Ability to collect, interpret in context, and analyze data from diverse sources and diverse formats (oral, written, and visual).

- Ability to promote a culturally aware, responsive, and diverse work environment.

- Leadership skills: Active listening; empathy; effective communication (as detailed above); strategic thinking; creativity; ability to inspire; flexibility; storytelling; ability to build trust.

Challenges in tribal liaison preparation in institutions of higher education

Having defined the roles, responsibilities, and traits of tribal liaisons, we point to several issues that challenge their cultivation within higher education institutions. In the following, we draw from our experiences in creating and operating the ESIL certificate at CU Denver. Open to students from any major, background, and experiential level, many of our experiences are common across non-Indigenous institutions in the United States and around the world (e.g., Eagle, 2015; Murray & Campton, 2023; Waterman et al., 2023; Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 2021).

Rigid or overcrowded course demands in disciplinary curricula

Undergraduate and graduate students from multiple disciplines are interested in contributing to ESIL. Although some programs and disciplines (e.g., communication, geography, or political science) might have space in their curricula for courses that contribute to the knowledge and skills listed in Box 2—and may even encourage their students to pursue them—other programs and disciplines may lack the curricular flexibility required to incorporate courses conducive to this education and training. In general, this is the case in STEM disciplines; in particular, engineering curricula are highly structured (Tseng et al., 2011), with little space for non-technical electives (unless, perhaps, they also meet the institution's general education requirements). Regardless of the case, the instruction and development of an effective tribal liaison require education and training above and beyond the minimum requirements of most undergraduate and graduate programs. This results in the need for extra financial and time commitments that impact the number of students that can acquire the necessary knowledge and skills of an effective tribal liaison.

Lacking or deficient human, financial, or institutional infrastructure

Many higher education institutions lack the necessary infrastructure (i.e., faculty, staff, courses, space, dedicated programs, or easy access to relevant location-based learning experiences) to provide efficiently and effectively the knowledge and skills that are fundamental for a tribal liaison. This challenge points to the importance of a collaborative approach not only between universities and Indigenous professionals, elders, and communities but also among higher education institutions for the provision of the necessary resources to educate and train the next generation of tribal liaisons. A recent initiative supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Native Food, Energy, and Water Systems (FEWS) Alliance, is initiating work on coordinating several higher education institutions for the creation of a Native FEWS certificate, modeled on the ESIL certificate, making use of educational and location-based resources from multiple institutions across the country.

Access to a curated repository of educational materials and resources

There are materials on Indigenous cultures, knowledge, and practices—books, journal articles, video documentaries, recordings of seminars, workshops, conference presentations, elders' presentations, etc.—that have been created over the years by diverse institutions for diverse purposes. Some were created by Indigenous practitioners and scholars, and others were not. These materials cover many topics, knowledge, and skills that are essential for a tribal liaison. Archiving and reutilizing some of these materials could inform tribal liaisons, bridging gaps in courses, programs, and institutions. However, this requires a well-organized and intense process of authentication, authorization, quality assurance, revision, organization, curation, and provision of access. Funding, staff, information technology infrastructure, and time will be required to create such a repository and make it widely accessible.

Limited access to immersive place-based experiences

In the strengthening and preparation of a skilled tribal liaison, it is helpful to spend time immersed in an Indigenous community, working with tribes, or shadowing tribal liaisons doing their work. Regardless of background and experience, all students need the experience of working across cultures. These experiences greatly contribute to recognizing and valuing Indigenous knowledge, cultures, and cosmology and to having a full appreciation and understanding of multiple complex issues and processes that cannot be effectively covered in a classroom setting. Unfortunately, access to these experiences is limited by multiple factors: geographical location, financial resources, available time, and the availability of communities, organizations, and tribal liaisons to host students. The value and impact of immersive place-based experiences in education have been documented (Johnson et al., 2020; Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 2021).

Risk of overwhelming Indigenous professionals, elders, and communities

Frequent requests to assist in teaching and sharing Indigenous cultures and science, or to host students as interns, might stretch the time and energy of Indigenous partners (Kennedy et al., 2023; Murray & Campton, 2023; Sambono, 2021). In our ESIL experience, Indigenous partners have been extremely generous with their time and knowledge. We focus on building reciprocal relationships with our partners. We constantly remind ourselves to be mindful when reaching out to them seeking their collaboration in strategic planning, educational activities, and engagement with the university community.

Benefits of extracurricular learning

Extracurricular learning is any activity outside the scope of a regular academic curriculum (Jackson & Bridgstock, 2021; Winstone et al., 2022). As such, it ranges widely in nature and in the role of the student (e.g., leader, participant). Among others, extracurricular learning includes social and cultural activities, workshops, internships, sports, student clubs, and volunteer work.

Several impacts related to participation in extracurricular learning are reported in the literature: enhancement of social and professional skills (e.g., Bohnert et al., 2007), sense of belonging (e.g., Buckley & Lee, 2021), improved well-being (e.g., Busseri et al., 2011), academic gains (e.g., Stuart et al., 2011), competence and skills development (e.g., Jackson & Bridgstock, 2021), confidence building (e.g., Kanar & Bouckenooghe, 2021), and improvement of employability (e.g., Clark et al., 2015; Winstone et al., 2022). More specifically, the following considerations have been identified as benefits and impacts of extracurricular learning on students, including Indigenous students (Johnson et al., 2020; King et al., 2021; Kuh, 2008; Sweat et al., 2013): reducing stress through finding friends and community; finding a space for self-care; developing a sense of belonging; helping students enjoy their studies and persist to graduation; development of skills (technical and professional) transferable to professional life after graduation; development of networks and relationships with peers, professors, and working professionals; development of professional advising and mentoring networks; enhancement of university courses and curriculum by incorporating Indigenous knowledges and skills into courses and curriculum; and giving visibility and presence to Indigenous cultures and science in the university and local communities. All these considerations support student retention and success.

Extracurricular learning can address several challenges, mentioned in the previous section, in preparing effective tribal liaisons in higher education institutions. In this paper, we focus on two types of extracurricular learning carried out within the context of the ESIL certificate at CU Denver: workshops and internships. These activities were designed with the purpose of complementing and enhancing regular university curricula in various disciplines (e.g., biology, engineering, geography, political science) by educating and training students in topics that are essential to achieve the ESIL mission and vision in preparing tribal liaisons (CU Denver, 2024b).

Certificate in ESIL

CU Denver is a public, urban research university situated on the ancestral homelands and unceded territories of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Ute. Its 12,250 undergraduate students are 39% white, 28% Hispanic, 12% Asian, 9% Black, 9% international, and 1% each Native American, Pacific Islander, and unknown (CU Denver, 2024c) making it the most diverse research university in Colorado. Nevertheless, CU Denver has comparatively few Indigenous students (or faculty), so academic programs generally do not contextualize themselves through Indigenous frameworks. In contrast, such contextualization is a strength of tribal colleges and universities (TCUs), but at the time the ESIL program was established in 2018, we had yet to form relationships with TCUs (that have been formed since). Recognizing the need for Indigenous leadership for curriculum development, ESIL reached out to a network of Indigenous STEM professionals working at various organizations to solicit their input on program development following the framework of collective impact (Kania & Kramer, 2011). That process of intentional community building will be the subject of a separate paper.

The ESIL program started at CU Denver in 2018 as a Design and Development Launch Pilot (DDLP) funded, in part, by NSF's program, named for the late Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson, called Inclusion across the Nation of Communities of Learners of Underrepresented Discoverers in Engineering and Science (INCLUDES). The goals of this launch pilot were (1) to develop a network of partners using the principles of collective impact (Kania & Kramer, 2011) and (2) to engage the network in the development and implementation of an ESIL certificate program at CU Denver. ESIL welcomed partnering representatives from public sector organizations and CU Denver faculty. The ESIL program also benefited from contributors from other public sector and non-profit organizations and institutions of higher education who participated for varying lengths of time, providing their expertise to advise strategic planning.

At the time of its creation in 2018, ESIL was a first-of-its-kind integrated higher education certificate, comprising curricular and extracurricular learning, focused on STEM students seeking to liaise on environmental issues between tribal and non-tribal organizations. In recent years, ESIL has expanded to include students from all disciplines. The ESIL program seeks to build on best practices for students and contribute lessons learned to the literature on the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) related to achievement, cultural navigation, and establishing symbiotic cultural and scientific identities. From the beginning, professional evaluators have documented and assessed program activities, evolution, and student feedback using the Indigenous evaluation framework (Velez et al., 2022).

EXTRACURRICULAR LEARNING IN ESIL: WORKSHOPS AND INTERNSHIPS

In this section, we describe the role of workshops and internships as part of the ESIL program and our experiences in carrying them out. Table 1 summarizes the number of workshops and internships in the five academic years from 2018/2019 through 2022/2023. Workshops and internships were created following the theory of culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Culturally relevant pedagogy posits that learning comprises the three interlocking elements of stuff, self, and society (Rice & Mays, 2022): Stuff refers to knowledge transmission; self refers to cultural competence, that is, understanding knowledge with respect to one's own culture and the culture of others; and society refers to placing knowledge and cultural competence in a broader sociopolitical context. By design, the workshops covered each of these elements multiple times. For example, stuff was captured through workshop topics on tribal law; self was captured through being a liaison, identity in STEM, and cultural competence; while society was captured in topics such as Indigenous law and politics. The internships were immersive experiences covering all three of these elements. Following workshops and internships, student feedback was collected following the Indigenous evaluation framework (Velez et al., 2022). Briefly, Indigenous evaluation replaces traditional evaluation, where the evaluator strives to be an impartial observer, with collaborative knowledge generation, where the evaluator strives to build trusting relationships (American Indian Higher Education Consortium, 2009). The success of the Indigenous evaluation framework in the present work is evidenced by the richness of the open-ended student feedback reported below.

| Academic year | Workshops | Internships |

|---|---|---|

| 2018/2019 | 4 | … |

| 2019/2020 | 6 | 3 |

| 2020/2021 | 7 | 5 |

| 2021/2022 | 7 | 2 |

| 2022/2023 | 6 | 1 |

| Sum | 30 | 11 |

Workshops

The ESIL certificate incorporates workshops to fill gaps in knowledge and skills not covered in courses and university programs and to create close ties between the university and students with Indigenous communities, knowledge holders, tribal liaison professionals, and organizations working with tribes. Those close ties, in turn, facilitate the transition of students from college to a career as a tribal liaison or professional working on Indigenous lands and issues. Workshops also bring to the university community a forum for educating students regarding Indigenous knowledge, skills, practices, culture, history, and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). Importantly, through the interactive discussions during and following each presentation, the workshops provide a mechanism for Indigenous students to have their voices heard. Last but not least, having a regular forum serves to reinforce a sense of community and a safe space for ESIL students.

A total of 30 workshops were carried out between academic years 2018/2019 and 2022/2023 (Table 1). Workshops were conducted by ESIL external partners, tribal liaisons, Indigenous community leaders, and knowledge holders, as well as Indigenous professors (Table 2). These 30 workshops included 36 individual presenters, 27 of whom (75%) are Indigenous students or professionals.

| Workshop no. | Topic | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Facilitation and public sector employment | 2/8/2019 |

| 2 | Traditional ecological knowledge | 4/5/2019 |

| 3 | Indigenous law and politics | 4/26/2019 |

| 4 | Tribal law 101 | 5/3/2019 |

| 5 | Traditional ecological knowledge | 10/25/2019 |

| 6 | Tribal law | 11/15/2019 |

| 7 | Protocols, decorum, and customs | 2/7/2020 |

| 8 | Career as a liaison | 3/6/2020 |

| 9 | Community and communication | 4/3/2020 |

| 10 | COVID-19 and emergency response | 5/1/2020 |

| 11 | Internships and safe space | 8/21/2020 |

| 12 | Race and racism | 9/18/2020 |

| 13 | Natives in STEM | 11/20/2020 |

| 14 | Evaluation and experiences | 1/22/2021 |

| 15 | The art of Indigenous plants, foods, and herbs | 2/19/2021 |

| 16 | Indigenous perspectives on environmental management | 3/19/2021 |

| 17 | Lakota Star Knowledge | 4/16/2021 |

| 18 | Fall welcome | 9/3/2021 |

| 19 | Field trip to Tall Bull Memorial Park | 10/1/2021 |

| 20 | Experiences as a native student and professional | 11/5/2021 |

| 21 | Extractive industries on Indigenous lands | 12/2/2021 |

| 22 | Spring welcome | 2/4/2022 |

| 23 | Lakota Star Knowledge | 3/4/2022 |

| 24 | The Iniquitous 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise | 4/15/2022 |

| 25 | Indigenous stewardship (podcasts) | 9/19/2022 |

| 26 | Land tenure issues and history in the Wind River Reservation, Wyoming (podcast) | 10/19/2022 |

| 27 | What does being a liaison mean to you? | 11/16/2022 |

| 28 | Open house | 2/24/2023 |

| 29 | Reconsidering the field of anthropology through the lens of an Indigenous CU Denver graduate student (podcast) | 4/28/2023 |

| 30 | Auraria Campus Powwow | 5/6/2023 |

Among the Indigenous professionals, job titles included General Engineer, Research Ecologist, and Senior Policy Director, so accordingly they brought authority, experience, and perspective to their workshops. In this way, Indigenous leadership was built into the ESIL certificate by design. They focused on topics around the following areas: tribal law, sovereignty, politics, and governance; Indigenous cultures, communication, protocol, and decorum; facilitation and negotiation; North American Indigenous history and current affairs; Indigenous leadership and decision making; skills and role of a tribal liaison in government and tribal organizations; and TEK. Initially, workshops consisted of half-day to full-day presentations mixed with activities related to one of the specific topics previously mentioned. The workshops were held on Fridays when most classes at CU Denver do not meet. After the COVID-19 pandemic and based on our initial experiences with the format and length of the workshops, their format and length were modified, as described in the Discussion.

Prior to assessment, the ESIL program was reviewed by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and exempted from human subject review (COMIRB Protocol 18-0133), and all assessment followed the Indigenous evaluation framework (Velez et al., 2022). A survey was administered after most workshops to obtain feedback from the students regarding the following two questions: (1) What is the most important information or message that you are taking from today's workshop? (2) What is something that you learned today that was either surprising to you or that is causing you to think about things differently? A total of 23 workshop reports were created based on these surveys. In addition to these reports, additional feedback on the workshops was gleaned from two ESIL students who specifically called out the field trip to Tall Bull Memorial Grounds on 10/1/2021 in their end-of-program comments prior to graduation.

Internships

From its inception, the incorporation of internships as part of the design of the ESIL certificate was strongly supported by the program's external partners, again reflecting Indigenous leadership. The internships are required to be carried out in Indigenous communities, organizations working on projects related to Indigenous lands or issues, or with tribal liaisons. The aim is to enrich the students' preparation with an immersive Indigenous-relevant professional experience to obtain several of internships' benefits reported in the literature (Binder et al., 2015; Galbraith & Mondal, 2020; Ismail, 2018; Lei & Yin, 2019): easing the college-to-career transition by developing professional networks and improving the students' resume and competitiveness for the job market, clarifying students' professional goals and desired career paths, increasing motivation and improving academic outcomes, developing professional advising and mentoring networks, and enhancing professional interpersonal, communication, political, negotiation, and leadership skills.

Eleven ESIL internships have been completed to date, as detailed in Table 3. Starting in 2021, at the end of their internship, students were requested to submit an internship reflection on the experience, including its impact, importance, and value. The prompt for these reflections comprised five questions: (1) What was your ESIL internship about? (2) For your internship, can you describe some of what you did and how it might have been impactful to you? (3) What was something you learned or did not expect from your internship experience? (4) How has your internship experience reinforced your career goals? (5) What skills, related to being a tribal liaison, did you use or were you exposed to? Five reflections were submitted, as well as one slide deck describing a certain student's internship. These six documents were used to assess the internship experience and to provide feedback to the ESIL leadership to support planning and program development.

| Internship no. | Year | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2020 | Private sector |

| 2 | 2020 | Public sector |

| 3 | 2020 | Tribal college |

| 4 | 2021 | Public sector |

| 5 | 2021 | Public sector |

| 6 | 2021 | Indigenous-serving college |

| 7 | 2021 | Research university |

| 8 | 2021 | Research university |

| 9 | 2022 | Public sector |

| 10 | 2022 | Study abroad |

| 11 | 2023 | Indigenous-serving college |

Coding methods

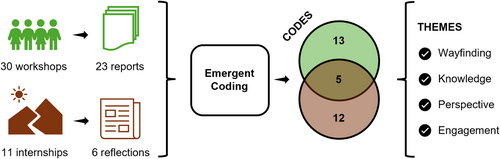

Workshop feedback and internship reports were analyzed using descriptive coding (Saldaña, 2013, pp. 87–91), which applies a short word or phrase to label the topic in a passage of qualitative data (Figure 1). Codes were emergent, being identified during coding, rather than being predetermined. Eighteen codes emerged from the workshop feedback; 17 codes emerged from the internship reports; five of these were common to both workshops and internships. Codes that appeared multiple times (at least three times among the 23 workshop reports or at least twice in the six internship reflections), including the five codes common to both workshops and internships, were used to marshal student responses categorized by code. However, although it appeared multiple times, the code COVID-19 was omitted because student responses under that code were entirely feedback on remote workshop logistics. Review of the student responses, categorized by code, revealed four emergent themes and associated subthemes. Student quotations to illustrate each theme or subtheme were copied verbatim from the workshop reports and internship reflections. Accordingly, this method preserves and promotes student voices as our sole source of qualitative data.

RESULTS

Student feedback provided in the workshop reports and internship reflections revealed four themes: (1) wayfinding, (2) knowledge, (3) perspective, and (4) engagement. Importantly, as these are all taken from student feedback, these themes reveal the actual impact of the extracurricular learning. Taken together, these themes highlight a wide spectrum of considerations relevant to training students for ESIL.

Wayfinding

Saying that [the workshop presenter] sought out an employer that didn't require him to leave his culture at the door was really interesting. This got me thinking about how … to promote that kind of an environment [at] work.

Thus, being a tribal liaison was recognized as a pathway supporting authentic participation by Indigenous STEM professionals. One student wrote that they were previously only considering employment with tribes or nonprofit organizations and that now, after their internship, they were also considering employment in the public sector. Another student stated that the September 2022 podcast on the National Park Service informed a potential career path with that agency. Thus, the workshops and internships provided opportunities for students to connect with careers and professionals, allowing students to see themselves doing the associated work.

Oral tradition is still the most powerful and impactful form of knowledge. Relating knowledge with stories, real-life experiences, it instills confidence. It is allowable to think differently, especially if English isn't the first language.

We talked about the language of [particular scientific perspectives] and how that can reinforce a patriarchal relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, and that this can be extremely painful to Indigenous peoples. Listening to this conversation is helping me grasp the importance of the language I use, how I should be interacting with the people my work impacts, and the deep historical wounds … Every ESIL experience is helping me to open my mind and broaden my exposure to different perspectives. I greatly value that.

Beyond these higher level observations about the importance of communication, students also commented on the practical value of the communication experience they gained through their internships, including a group presentation on lead (Pb) concentration and an elevator pitch describing a research paper. Two interns commented on the value of making an oral presentation to communicate with various parties related to environmental stewardship.

Knowledge

The second theme is knowledge, where students pointed to specific information gained through the workshops. At the most basic level, workshops provide instruction on topics relevant to the work of a tribal liaison. Over four workshops, students learned some of the history of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe, the National Park system, the Sand Creek Massacre, and Tall Bull Memorial Grounds—a space in Denver Mountain Parks officially stewarded by Denver's Indigenous community. In addition to history, over two workshops, students reported learning tribal resource economics, including the basic technology of hydraulic fracturing and the protests surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline. Notably, two different Indigenous STEM professionals offered two different perspectives on oil and gas development, emphasizing the important point that different tribes make different decisions and underscoring the importance of nuance when discussing ESIL. The breadth of knowledge presented provided an opportunity for individualization of education and experience as students navigate ESIL and their training as liaisons.

Under the theme of knowledge, two important subthemes emerged: law and TEK. Students noted that tribes, states, and the federal government have different perspectives on Indian law. One student noted that there had been some recent positive outcomes for tribes through legal efforts, which motivated them to support future legal efforts, although it should be noted that, at least before the mid-20th century, the overall record of tribes in federal courts has been overwhelmingly negative (Fletcher, 2014). Students gained knowledge of federal Indian law, specifically mentioning the case of Cherokee versus Georgia and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. Students also reflected on a number of legal ideas, for example, the observation that the land that constitutes the modern city of Denver was taken without legal repercussion.

Students also contrasted the Indigenous legal goal of restoration versus the non-Indigenous legal goal of retribution and noted the complexity of the legal system, where—for example—the US Department of Justice may take sides. Students also reflected on Indian law beyond the United States, reflecting on a podcast that described how an early draft of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples had been edited to the detriment of Indigenous peoples.

Anyone can present on material related to Indigenous knowledges, but that material can be rendered meaningless if the presenter doesn't have an appreciation for or connection to the land that that knowledge comes from.

Perspective

I also was grateful for [the speaker's] realization about how he stays composed when talking about these topics.

Indeed, the subtheme of managing challenges was also reflected in student comments on the internships. One student's internship was hampered by an unexpected delay in their background check by the hosting organization. Another student, while presenting the results of their internship, was surprised to encounter interpersonal and intergroup politics whose resolution required intervention by the internship mentor. These politics arise from the notion, expressed in other student feedback, that different tribes have different perspectives and that there are complex relationships between tribal, state, and federal governments. One student recognized that being a tribal liaison means that there are multiple perspectives, and although decisions are required, one cannot force parties into agreement. Another student wrote that with “many moving parts,” liaisons have a duty to inform each side, rather than advocating for just one side. Taken together, these experiences helped students to begin developing the perspective required to be an effective tribal liaison.

Engagement

The fourth and final theme is engagement. That is, having been exposed to the potential career path of a tribal liaison, having gained relevant knowledge, and having developed some nuanced perspectives, how did students feel about the workshops and internships? Multiple students articulated how the workshops had reinforced their motivation to attend college, major in STEM, and participate in ESIL. Students wrote of helping others, finding common ground, and not giving up on their education or career. Specifically, students wrote that ESIL provided “opportunity to make a difference,” that “my education will not go unused,” and that “I will be able to live out my passion.” One student summarized this sentiment by writing that they were driven to “directly contribute to the betterment of my community on a daily basis.” In contrast to typical academic seminars, student feedback was emotional: One student was encouraged by a workshop speaker's dual identity (i.e., a speaker who was part Indigenous); another student wrote that a certain workshop put their own feelings into words; and another student expressed gratitude for the part they played to support environmental stewardship during their internship: “Being able to play a part in that is almost too overwhelming for words.”

Complementing these individual emotional reflections was a desire to connect with a broader community. This was reflected in several students' desire to connect with ESIL students and mentors, and in one student's internship report, where they reported bonding with other students from marginalized identities. In particular, the October 2021 field trip to Tall Bull Memorial Grounds was an important opportunity, after 18 months of pandemic restrictions, to meet the ESIL community in person. One student wrote, “I surely missed everyone and was grateful I got to see everyone again.” Indeed, against a backdrop where Indigenous students often feel alienated at non-Indigenous colleges, the sense of community was especially important. In other words, beyond the wayfinding, the knowledge, and the nuanced perspective, students reported positive feelings of inclusion. As one student summarized, “I can be Indigenous without having to explain it.”

DISCUSSION

Here, we would like to revisit our results using the frameworks of Indigenous evaluation, culturally relevant pedagogy, and TEK before moving to a more empirical summary of challenges encountered and benefits provided. We do this in order to place our results both within our specific goal of preparing tribal liaisons and within the larger literature examining how academic programs can serve Indigenous students more effectively.

The effectiveness of the Indigenous evaluation framework is evidenced by the richness of the student feedback reported above. We suggest this resulted from the evaluators personally attending all the workshops, both in-person and online, which provided an opportunity for the students to become familiar with the evaluators. In fact, evaluation itself was the subject of workshop 14 “Evaluation and Experiences.” The framework of culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995) informed the breadth of workshop topics (Table 2), and the positive tenor of student feedback indicates its effectiveness. One can also draw connections between the four themes reported here and the framework of TEK as cultural transmission of knowledge, practices, and beliefs (e.g., Charles & Cajete, 2020). The first theme of wayfinding, and especially the subtheme of communication, relates to cultural transmission. The second theme of knowledge is, of course, a named element in TEK, but the fact that students identified TEK as a component of knowledge emphasizes that this knowledge is relational rather than hierarchical. The third theme of perspective, and especially the subtheme of managing challenges, relates to the TEK element of practice. And the fourth theme of engagement reinforces the TEK element of belief, that is, students do the work because they believe in community.

Carrying out the ESIL extracurricular activities was not without challenges. CU Denver is an urban commuter campus, and most of the students work part- or full-time. Friday, when most classes do not meet and when we scheduled the workshops, is also a full day that students often devote to their jobs for income. Students (particularly those with dependents) found it difficult to devote a half day or a full day above and beyond their academic and work schedules to participate in workshops. These situations are common among students (King et al., 2021). Several of the presenters in the workshops were Indigenous external partners, community members, or faculty members with very busy schedules. We had to be very selective in asking them for the time and expertise to avoid Native presenters' fatigue as described by Sambono (2021) and Murray and Campton (2023).

These considerations notwithstanding, before the COVID-19 pandemic triggered the cancellation of most in-person gatherings at CU Denver, student participation in-person on-campus workshops was strong and consistent. After COVID, we experienced a decline in participation for in-person workshops. We elicited feedback from students regarding the reasons for this change. The pre-pandemic issues remained (e.g., overcommitment, need for income) and post-pandemic concerns such as participation in gatherings became a new issue. Also, we postulate that there was a general change in expectations for in-person participation in academic endeavors. In response, we modified the length, format, and number of workshops per semester. We tried shorter meetings, hybrid and fully remote participation, and we reduced the number of workshops during our 15-week semesters.

During the 2023/2024 academic year, recognizing that workshop participation had still not recovered to its pre-pandemic level, the ESIL program experimented with a new workshop format that was both remote and asynchronous. Rather than scheduling specific workshops, the ESIL program offered a menu of activities the students can do at their leisure (e.g., readings, video documentaries, or participation in events organized by the university's office of American Indian Student Services). After choosing one or more activities, students were requested to submit a short reflection highlighting the main points learned, points of agreement and disagreement, and how the activity may have changed the student's perspectives. In spring 2024, we offered token incentives (e.g., small-denomination gift cards and university merchandise) for on-time participation. Despite these incentives, very few reflections were submitted by the end of spring 2024. The positive feedback from the asynchronous workshops is that they are more accessible to complete at their own pace and to fit into hectic schedules. However, there has been a disconnect with the online format, as one student summarized, “It is not as engaging … I miss being able to talk about what is relevant.”

Regarding our experience in setting up and carrying out internship experiences, we have encountered the following challenges: Students often cannot relocate for an extended period (e.g., 2–8 weeks) to work with a tribal liaison or Indigenous community due to family or job commitments; lack of funding to support students' living expenses and to cover lost income from students' nonacademic employment; limited access to Indigenous organizations, communities, or tribal liaisons due to their location or busy schedules; and certain public sector onboarding processes (e.g., background check, systems access) that can delay internships by several weeks.

Despite these challenges, the benefits of the workshops and internships are significant as described by the students themselves, as detailed in the previous section. Immersive place-based experiences, even for short periods of time, are particularly important for the acquisition of Indigenous knowledge and skills given that many of them can only be gained effectively by interacting in context with elders, Indigenous communities, or tribal liaisons. In our experience, actions that would facilitate student participation in extracurricular learning are the following: (1) institutional and financial support for academic programs and offices (e.g., experiential learning office) that offer incentives to help students cover the opportunity cost of their participation; (2) programs dedicated to creating community and support for Indigenous students, such as CU Denver's office of American Indian Student Services; and (3) providing academic credit for participation in Indigenous culturally-relevant workshops, community service, and other experiential activities. The benefits of workshops and internships reported in the students' reflections closely match those reported in the literature (Binder et al., 2015; Galbraith & Mondal, 2020; Ismail, 2018; Lei & Yin, 2019): improved public speaking, professional presentations, and reporting; improved clarity of future career path; professional networking; learning in context, hands-on, and directly from interested parties involved in projects and decision-making; dealing with uncertainty and changes; and help in “finding my place” in the academic world. In particular, the workshops and internships have provided an opportunity for students to develop the perspective required to work with wicked problems for which there is no obvious solution (e.g., Chapin et al., 2008; Karanasios & Parker, 2018).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Our experiences conducting extracurricular workshops and internships support the benefits and challenges reported in the literature (Johnson et al., 2020; King et al., 2021; Kuh, 2008; Sweat et al., 2013). Their role and benefits are particularly important for students aiming to develop careers as tribal liaisons. The ESIL workshops and internships provide culturally relevant Indigenous knowledge and skills that are difficult to acquire in traditional classrooms or rigid disciplinary curricula. The workshop activities, when conducted in-person or even online synchronously, had the added benefit of providing a safe place and supportive environment for sharing and communicating about the topics covered, as well as broader issues related to the students' identity and their role in academia and their future careers.

From its design and later operation, ESIL emphasized Indigenous leadership through collaborations with external Indigenous partners (tribal liaisons, knowledge holders, community leaders) for planning, activities, and program development. Students' feedback highlights the value of having their presence on campus in helping them grapple with the challenges of representing multiple perspectives within liaison work.

The emphasis on networking beyond the university and on the participation of Indigenous external partners with whom long-term internship agreements can be established is recommended to facilitate the creation of meaningful professional experiences. The setting of culturally relevant internships requires careful planning with plenty of lead time (several months) before starting. The intern onboarding usually is a long and sometimes complicated process. Students' financial restrictions, as well as academic and personal commitments, may limit their ability to participate in long internships or extended relocations. Ideally, dedicated financial resources for students should be available for these experiences.

There are multiple educational resources such as recorded presentations by academics, knowledge holders, community leaders, and tribal liaisons, as well as best-in-class books and articles, which can support the development of workshop activities. Recently, we have started an effort to identify access to these resources and organize some of them around the knowledge and skills that have been identified as essential for the inclusion of appropriate content to provide a deep understanding of a culturally effective liaising. A coordinated national (and possibly international) level effort to create a database of these resources would be valuable for incorporating Indigenous cultures, science, and traditional knowledge into mainstream academia to shape and nurture the development of the future leaders in this profession.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank associate editor Jennifer Momsen and two anonymous referees for their constructive feedback. This work would not have been possible without the workshop presenters and internship hosts whose contributions are listed in Tables 2 and 3, nor would it have been possible without the many students who shared written feedback through The Evaluation Center. Funding was provided through the NSF awards 1742603 and 1744524. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of presenters, hosts, students, or funders.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are sensitive and cannot be provided publicly because they are confidential student feedback.