Homeless persons' experiences of health- and social care: A systematic integrative review

Abstract

Homelessness is associated with high risks of morbidity and premature death. Many interventions aimed to improve physical and mental health exist, but do not reach the population of persons experiencing homelessness. Despite the widely reported unmet healthcare needs, more information about the barriers and facilitators that affect access to care for persons experiencing homelessness is needed. A systematic integrative review was performed to explore experiences and needs of health- and social care for persons experiencing homelessness. The following databases were searched: AMED, ASSIA, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Cochrane library, Nursing and Allied Database, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection. Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria of empirical studies with adult persons experiencing homelessness, English language, and published 2008-2018. Fifty percent of the studies were of qualitative and quantitative design, respectively. Most studies (73%) were conducted in the United States (n=11) and Canada (n=5). The analysis resulted in three themes Unmet basic human needs, Interpersonal dimensions of access to care, and Structural and organizational aspects to meet needs. The findings highlight that persons in homelessness often must prioritize provision for basic human needs, such as finding shelter and food, over getting health- and social care. Bureaucracy and rigid opening hours, as well as discrimination and stigma, hinder these persons’ access to health- and social care.

1 INTRODUCTION

Homelessness is an increasing problem worldwide (EU, 2013; US, 2018), and previous research highlights that persons experiencing homelessness are disproportionately affected by physical and mental illness, substance abuse and long-term burden of chronic diseases compared to housed persons (van Dongen et al., 2019; Lebrun-Harris et al., 2013; Lewer et al., 2019). Homeless populations, that is, individuals without permanent housing who may live on the streets; stay in a shelter, mission, single room occupancy facilities, abandoned building or vehicle; or in any other unstable or non-permanent situation (US, 2018), face huge health inequities across a wide range of health conditions (Aldridge et al., 2018). Persons experiencing homelessness are three times more likely to report chronic diseases with asthma, COPD, epilepsy and heart problems being prevalent (Lewer et al., 2019). Older persons (>50) experiencing homelessness have multiple health problems that remain unaddressed by healthcare services, often lack social support and do not explicitly express their own healthcare needs (van Dongen et al., 2019), resulting in higher use of acute care. The excess mortality associated with considerable social exclusion, such as homelessness, is extreme (Aldridge et al., 2018; Fazel, Geddes, & Kushel, 2014; Slockers, Nusselder, Rietjens, & van Beeck, 2018), that is, the mortality rate is nearly eight times higher than the average for men and 12 times higher for women (Aldridge et al., 2019, 2018), with an average age for death at 52 years.

The origins of homelessness are multi-faceted, both on individual and structural levels, for example the ageing population (van Dongen et al., 2019; Fazel et al., 2014), changes in the housing market with shifts in family structures (NBHW, 2017), migration (EU, 2013), rising costs for housing (NBHW, 2017) and poor health (van Dongen et al., 2019; Fazel et al., 2014; Lewer et al., 2019). A growing body of research concludes that homelessness is associated with heavy costs for society with regards to public health, social and legal services (Basu, Kee, Buchanan, & Sadowski, 2012; Fuehrlein et al., 2015; Larimer et al., 2009; Mitchell, Leon, Byrne, Lin, & Bharel, 2017; Suh et al., 2016). However, the samples in the studies often consist of highly selected subgroups, like individuals with a certain specific diagnosis or demographic criteria like ethnicity or gender orientation, making comparisons and inferences challenging. At the same time, tri-morbidity, defined as a combination of poor physical health, poor mental health and drug or alcohol misuse (Hewett, Halligan, & Boyce, 2012) is a suggested characteristic in long-term homelessness, further illustrating the complexity of designing and providing health- and social care interventions for persons experiencing homelessness.

- What experiences do persons experiencing homelessness have of health- and social care?

- What are the needs of persons experiencing homelessness with regards to health- and social care?

- How does organisation of health- and social care (structure, process, outcomes) affect persons experiencing homelessness?

- Is there evidence of cost-effectiveness being a barrier to integration and co-ordination of social- and healthcare for persons experiencing homelessness?

2 METHODS

A systematic integrative review was selected as the method allows findings from a diverse range of research methods to provide a breadth of perspectives and a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). This review comprehensively explored the complexities and the interface of health- and social care as experienced by persons in homelessness. The Centre of Dissemination and Research (CDR) guidelines for systematic reviews in healthcare (CDR, 2009) were used to guide the structure and process of the review.

2.1 Literature search strategy

Initially, the PROSPERO protocol database at York University was searched for systematic reviews close to our aim and topic. Since none were found, a PROSPERO protocol for our review was constructed to outline the literature search strategy and relevant parameters for data evaluation and analysis (NHS, 2018; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

For a comprehensive literature search, aligned with the aim and research questions, the following electronic databases were searched in January 2018: AMED (The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database), ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts), Academic Search Complete, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Cochrane library, Nursing and Allied Database, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection. These databases were searched with search strings comprising our four key concepts from the problem identification and the research questions: (a) persons experiencing homelessness; (b) experiences OR perceptions; (c) delivery of healthcare, healthcare sector, outcome assessment, comprehensive healthcare, patient care team, health personnel, social work, health services research; (d) economics, costs and cost analysis, markov chains, monte carlo method, quality-adjusted life years, models, statistical, value of life. The terms used in our searches were derived from our aim and research questions, and were searched for and selected by indexation in the MeSH-database. All search terms used were Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) except for the words experiences and perceptions.

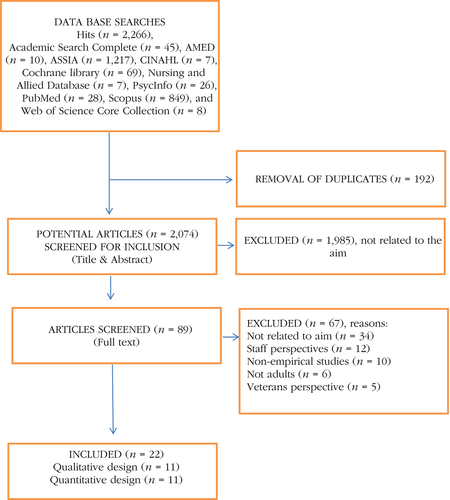

Articles from the searches were imported into Rayyan software for continuing screening and data evaluation of titles and abstracts. These were independently screened and evaluated by two authors (AK, ÅC). Ensuing disagreements were subsequently discussed in a meeting with another author (EM) to reach consensus. When articles were included for full-text screening and evaluation, two authors (AK, ÅC) independently screened and evaluated all articles which again were discussed in a research team meeting. After the selection of relevant articles for inclusion, the reference lists were hand searched for identification of further articles meeting the inclusion criteria, see PRISMA flow diagram (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009), Figure 1.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Empirical studies (original quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods research studies as well as multiple case studies) about adult (over 18 years of age) experiences and needs of health- and social care in persons experiencing homelessness, published in English between January 2008 and January 2018 were included. This timeframe was selected to give focus and boundaries to the search (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Systematic reviews, editorials, commentaries or letters, discussion papers, opinion papers and other non-empirical studies were excluded. Articles about war veterans and healthcare professionals’ perspectives were also excluded, to provide focus and boundaries to our review. War veterans’ experiencing homelessness constitutes a unique segment of persons experiencing homelessness, with complex needs and challenges, and were not in the scope of this review.

2.3 Data evaluation and quality assessment

Quality of the evidence in the included studies was assessed by two authors (AK, ÅC) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) guidelines (CASP, 2018) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) hierarchy of evidence (Harbour & Miller, 2001). The quality scores were calculated for each study. The raters had a maximum difference of one point in sum scores and were in total accordance for inclusion of the studies, see Appendix S1. Quality was not used to exclude studies, but to focus attention on strengths and weaknesses of the studies.

2.4 Data reduction, display, comparison and drawing conclusions

Results from the included articles were extracted according to data reduction classification and codes, independently by two authors (AK, ÅC), see template in Appendix S1. Then the data were compared, analysed and synthesised using thematic analysis identifying similarities, differences and patterns (Sandelowski & Leeman, 2012). All authors read the full-text articles in combination with detailed summaries of the included studies, and participated in data display, data comparison and development of themes and sub-themes. The iterative process required approaching and displaying data in different ways to allow shifting perspectives and ensuring robust analyses (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). This entailed shifting from being close to the text in individual articles to zooming out and looking at the whole, aiming to see the bigger emerging picture. The thematic analysis entailed independent reading and pondering, written communications with reflections and two full-team analysis meetings with discussions for consensus and conclusion drawing, including verification of findings (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

3 FINDINGS

3.1 Overview of the studies

Twenty-two studies relevant to our aim and research questions were included in the review, 11 quantitative (Asmoredjo, Beijersbergen, & Wolf, 2017; Baggett, O'Connell, Singer, & Rigotti, 2010; Hwang et al., 2010; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Kertesz et al., 2014; van Laere, de Wit, & Klazinga, 2009; Robbins, Wenger, Lorvick, Shiboski, & Kral, 2010; Uddin et al., 2009; Vuillermoz, Vandentorren, Brondeel, & Chauvin, 2017; Whelan et al., 2010; Zur & Jones, 2014), and 11 qualitative (Biederman, Gamble, Manson, & Taylor, 2014; Biederman, Nichols, & Lindsey, 2013; Bungay, 2013; Corrigan, Pickett, Kraus, Burks, & Schmidt, 2015; Gültekin, Brush, Baiardi, Kirk, & VanMaldeghem, 2014; Kryda & Compton, 2009; Martins, 2008; McLeod & Walsh, 2014; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Voronka et al., 2014). We found no studies that described economic costs in conjunction with needs of health- and social care in persons experiencing homelessness. However, two studies discuss monetary and human costs related to absent medical respite care for these persons (Biederman et al., 2014), and lack of dental and medical insurance among injection drug users experiencing homelessness (Robbins et al., 2010).

See Appendix S1 for a presentation of research aims, population foci, methods, samples, key findings and SIGN scores in the included articles. To summarise, 11 studies were conducted in the United States (50%) (Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014, 2013; Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Kertesz et al., 2014; Kryda & Compton, 2009; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Robbins et al., 2010; Zur & Jones, 2014), five in Canada (23%) (Bungay, 2013; Hwang et al., 2010; McLeod & Walsh, 2014; Voronka et al., 2014; Whelan et al., 2010), two in the Netherlands (9%) (Asmoredjo et al., 2017; van Laere et al., 2009), two in the United Kingdom (9%) (Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Rae & Rees, 2015), one in Bangladesh (4.5%) (Uddin et al., 2009) and one in France (4.5%) (Vuillermoz et al., 2017). The population foci in 12 studies (55%) were persons experiencing homelessness in general (Asmoredjo et al., 2017; Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; Hwang et al., 2010; Kertesz et al., 2014; Kryda & Compton, 2009; van Laere et al., 2009; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Uddin et al., 2009; Voronka et al., 2014), whereas foci in three studies, respectively, were family homelessness (14%) (Gültekin et al., 2014; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Vuillermoz et al., 2017) and homelessness among women (14%) (Biederman et al., 2013; Bungay, 2013; McLeod & Walsh, 2014). Other population foci (17%) were: African Americans with mental illness experiencing homelessness (Corrigan et al., 2015), injection drug users experiencing homelessness (Robbins et al., 2010), persons visiting a mobile health unit experiencing homelessness (Whelan et al., 2010) and persons visiting federally qualified health centres in the USA experiencing homelessness (Zur & Jones, 2014). In five studies (23%), the samples consisted of only women (Biederman et al., 2013; Bungay, 2013; Gültekin et al., 2014; McLeod & Walsh, 2014; Vuillermoz et al., 2017), whereas Biederman et al. (2014) did not report the proportion of females/males that participated in their study. Numbers of study participants in included studies ranged between 6 (Biederman et al., 2014) and 1,191 (Hwang et al., 2010). Participants’ age was not reported in five studies (Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2015; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Martins, 2008; Voronka et al., 2014). Three studies used peer interviewing (participatory research) (Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Voronka et al., 2014). The SIGN scores of the included studies ranged between 2+ and 3.

The analysis resulted in three themes: Unmet basic human needs; Interpersonal dimensions of access to care and Structural and organisational aspects to meet needs, represented by nine sub-themes. See Table 1 for sub-themes in relation to included articles.

| Unmet basic human needs | |

| Struggle to accommodate basic human needs | Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; Bungay, 2013; Corrigan et al., 1997; Gültekin et al., 2015; Martins, 2015; McLeod & Walsh, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2018; Rae & Rees, 2015; Uddin et al., 2009; van Laere et al., 2009; Vuillermoz et al., 2017; Zur & Jones, 2014. |

| Unmet healthcare needs | Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 1997; Hwang et al., 2012; Kertesz et al., 2011; Martins, 2015; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2018; Rae & Rees, 2015; Robbins et al., 2010; Uddin et al., 2009; van Laere et al., 2009; Vuillermoz et al., 2017; Zur & Jones, 2014. |

| Lacking resources to accessing care | Baggett et al., 2010, Biederman et al., 2014, Corrigan et al., 2015, Jenkins & Parylo, 2011, Kertesz et al., 2014, Martins, 2008, Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009, Rae & Rees, 2015, Robbins et al., 2010, Uddin et al., 2009, Vuillermoz et al., 2017, Zur & Jones, 2014. |

| Unmet social needs | Asmoredjo et al., 2017, Biederman et al., 2014, Corrigan et al., 2015, Gültekin et al., 2014, Kryda & Compton, 2009, McLeod & Walsh, 2014, van Laere et al., 2009. |

| Interpersonal dimensions of access to care | |

| Unhelpful relations | Bungay, 2013, Corrigan et al., 2015, Gültekin et al., 2014, Jenkins & Parylo, 2011, Kryda & Compton, 2009, Martins, 2008, McLeod & Walsh, 2014, Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009, Rae & Rees, 2015, Voronka et al., 2014. |

| Stigmatised and discriminated | Bungay, 2013, Corrigan et al., 2015, Gültekin et al., 2014, Kryda & Compton, 2009, Martins, 2008, Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009, Rae & Rees, 2015, Voronka et al., 2014. |

| Supportive relations | Asmoredjo et al., 2017, Biederman et al., 2013, Jenkins & Parylo, 2011, McLeod & Walsh, 2014, Rae & Rees, 2015, Whelan et al., 2010, Voronka et al., 2014. |

| Structural and organisational aspects to meet needs | |

| Structural and organisational barriers | Asmoredjo et al., 2017, Bungay, 2013, Corrigan et al., 2015, Hwang et al., 2010, Kertesz et al., 2014, Kryda & Compton, 2009, Martins, 2008, McLeod & Walsh, 2014, Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009, Rae & Rees, 2015, van Laere et al., 2009, Voronka et al., 2014. |

| Organisation to meet multi-faceted needs | Biederman et al., 2014, Biederman et al., 2013, Corrigan et al., 2015, Gültekin et al., 2014, Jenkins & Parylo, 2011, Kryda & Compton, 2009, McLeod & Walsh, 2014, van Laere et al., 2009, Whelan et al., 2010, Voronka et al., 2014. |

3.2 Review findings on ‘Unmet human needs’

Persons experiencing homelessness describe that they suffer from medical and psychiatric morbidity as well as social deprivation related to poverty and homelessness. They express that their needs are often overlooked by health- and social care, but also describe that they neglect seeking care due to deficits related to basic human needs that must be prioritised first. Findings related to the theme Unmet human needs is represented by four sub-themes: struggle to accommodate basic human needs; unmet healthcare needs; lacking resources to accessing care and unmet social needs.

In 11 studies, persons experiencing homelessness reported how they struggle to accommodate basic human needs, that is, finding food, water, security and shelter (Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; Bungay, 2013; Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; van Laere et al., 2009; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Uddin et al., 2009; Vuillermoz et al., 2017). Food insecurity and lack of nutrition was highlighted (Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Vuillermoz et al., 2017), especially in the light of being exposed to weather and the elements (Corrigan et al., 2015). Struggling to manage daily life without laundry facilities or space for managing personal hygiene practices were described (Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; van Laere et al., 2009; McLeod & Walsh, 2014; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Uddin et al., 2009). Financial struggles and lack of money were other reasons for unmet basic human needs (Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; van Laere et al., 2009; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Uddin et al., 2009; Zur & Jones, 2014).

Unmet healthcare needs were reported in 13 studies (Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2015; Hwang et al., 2010; Kertesz et al., 2014; van Laere et al., 2009; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Robbins et al., 2010; Uddin et al., 2009; Vuillermoz et al., 2017; Zur & Jones, 2014). Highest prevalence of unmet need in the past 6 months (82%) was reported in a study of injection drug users in the United States (Robbins et al., 2010), whereas the lowest prevalence of unmet healthcare needs (17%) was reported in a study from Canada (with universal healthcare), investigating a mixed population of persons experiencing homelessness (Hwang et al., 2010). Need for dental and oral healthcare were reported in five studies, all from the United States (Baggett et al., 2010; Kertesz et al., 2014; Robbins et al., 2010; Vuillermoz et al., 2017; Zur & Jones, 2014). Highest prevalence of oral healthcare needs (63%) was self-reported by injection drug users in Robbins et al. (2010) and lowest (41%) as reported by participants in Baggett et al. (2010). In addition, the absence of dental care for persons with mental illness experiencing homelessness was described in one study (Corrigan et al., 2015). Persons experiencing homelessness through interviews described concerns and worries related to unmet healthcare needs, like managing care after surgery, needing help with discharge planning and having access to shelters with medical resources, as well as programs for women's health, HIV/AIDS care and mental health (Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2015). Homeless persons with chronic conditions for example arthritis, cardiac failures, diabetes, digestive issues and HIV/AIDS, were described as particularly vulnerable for unmet healthcare needs (Corrigan et al., 2015). Women (n = 350) experiencing homelessness in Bangladesh described needs for obstetric, maternity and gynaecological care, more specifically 39% having concerns with vaginal discharge, 13% having lower abdominal pain and 12% with general itching/burning (Uddin et al., 2009). Furthermore, care for substance use disorder (Robbins et al., 2010), and transitional care after being discharged from hospital were described as important by persons experiencing homelessness (Biederman et al., 2014).

Lacking resources to accessing care was described in 12 studies (Baggett et al., 2010; Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2015; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Kertesz et al., 2014; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Robbins et al., 2010; Uddin et al., 2009; Vuillermoz et al., 2017; Zur & Jones, 2014). Reasons were: not being covered by insurance or the healthcare system (Baggett et al., 2010; Corrigan et al., 2015; Kertesz et al., 2014; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009), lacking identification (Corrigan et al., 2015), mail and telephone (Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009), poor transportation (Gültekin et al., 2014; Kertesz et al., 2014; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009) and cuts in dental coverage (Robbins et al., 2010). Examples of strategies employed when meeting these barriers were: giving up medical care (Rae & Rees, 2015), lying about identity to receive care, volunteering for research to get medications, modifying doses to make medications last, choosing jail for the resources available there (Corrigan et al., 2015) and to withhold information (Bungay, 2013). Other factors described through surveys as barriers to accessing care, one of them a quality improvement project, included not knowing where to go (Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Kertesz et al., 2014; Uddin et al., 2009; Zur & Jones, 2014), and lacking awareness of healthcare needs (Uddin et al., 2009).

Unmet social needs were described in seven studies (Asmoredjo et al., 2017; Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Kryda & Compton, 2009; van Laere et al., 2009; McLeod & Walsh, 2014). Lack of social support and social network was described by persons experiencing homelessness in studies by Biederman et al. (2014) and Gültekin et al. (2014). Quality improvement was thought to be needed in shelters in the Netherlands (Asmoredjo et al., 2017), and persons experiencing homelessness in the USA and Canada, highlighted that shelters must be safe (Kryda & Compton, 2009; McLeod & Walsh, 2014) and out of reach from drug and alcohol provision. Furthermore, both shared spaces and secure spaces for privacy were described as crucial in shelter design by persons experiencing homelessness in the USA and Canada (Biederman et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2015; McLeod & Walsh, 2014).

3.3 Review findings on ‘Interpersonal dimensions of access to care’

Findings highlight that professional encounters and relationships play an important role during times of homelessness, when the need of personal support may be increased, but the social network reduced. Being cared for and respected in the professional relationship are described as supportive, while experiences of alienation, discrimination, disrespect and stigmatisation are experienced as unhelpful. The unhelpful aspects of professional relationships were described as having a negative effect on persons’ well-being, willingness to seek care and perceived access to care. Findings related to the theme Interpersonal dimensions of access to care are represented by three sub-themes: unhelpful relations; stigmatised and discriminated and supportive relations.

Ten studies reported findings related to unhelpful relations with health- and social care professionals (Bungay, 2013; Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Kryda & Compton, 2009; Martins, 2008; McLeod & Walsh, 2014; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Voronka et al., 2014). Being treated with a lack of respect by health- or social care professionals, for example lack of caring, empathy and understanding, was described in several studies (Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Martins, 2008; Voronka et al., 2014). In Bungay's qualitative study (2013), comprising field studies and interviews with 67 street-involved women in an inner-city area, women described experiences of being judged by appearance or previous history of mental illness, substance abuse or homeless status. Similar findings came to light in qualitative studies by Gültekin et al. (2014) using focus groups with 13 mothers experiencing homelessness, Martin's (2008) phenomenological study with 15 persons experiencing homelessness, the nine persons experiencing homelessness in Nickasch and Marnocha's study (2009) using grounded theory, and in Voronka et al.s. (2014) exploratory study with 30 individuals experiencing homelessness. Feelings of mistrust were described by the 24 persons experiencing homelessness interviewed in Kryda and Compton's study (2009), and Martins (2008) further described experiences of being invisible. Persons experiencing homelessness further described being disappointed because perceived promises from social workers were not kept (Kryda & Compton, 2009), and there were experiences of not being listened to (Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; Rae & Rees, 2015). Also, health issues were not addressed since individuals experiencing homelessness did not feel welcome, nor cared for, when seeking medical attention (Bungay, 2013; Rae & Rees, 2015). Advice given was unrealistic, and resulted in persons refraining from seeking healthcare again.

Eight studies reported findings related to experiences of being stigmatised and discriminated during encounters with health- and social professionals (Bungay, 2013; Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Kryda & Compton, 2009; Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015; Voronka et al., 2014). Experiences included paternalism and humiliation in encounters with professionals (Bungay, 2013; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Voronka et al., 2014), being dehumanised (Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015) and of healthcare professionals insensitivity to ethnic disparities or unique needs of people of colour (Corrigan et al., 2015). Furthermore, persons experiencing homelessness described being labelled and stigmatised when seeking healthcare (Martins, 2008; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009), not being treated as individuals with unique needs, and receiving substandard care (Rae & Rees, 2015). Experiences of loss of freedom, or having ones’ rights infringed upon, were also described by persons experiencing homelessness seeking social care (Voronka et al., 2014).

In seven studies, persons experiencing homelessness described supportive relations with health- and social care professionals (Asmoredjo et al., 2017; Biederman et al., 2013; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; McLeod & Walsh, 2014; Rae & Rees, 2015; Voronka et al., 2014; Whelan et al., 2010). Positive experiences of client- professional encounters or relationships described by persons experiencing homelessness were social interactions, being able to share vulnerability and laugh together with professionals (Biederman et al., 2013). Other positive experiences included supportive attitudes from healthcare staff (Jenkins & Parylo, 2011), flexibility regarding appointments with the general practitioner (Rae & Rees, 2015) and social workers who were welcoming and provided opportunities for participation in shelter life and community (McLeod & Walsh, 2014). Caring was experienced when health- and social professionals took time to listen, remembered details about their life and catered to individual resources and needs (Biederman et al., 2013; Rae & Rees, 2015). Being invited to participate in decision-making in shelters (McLeod & Walsh, 2014) as well as social professionals demonstrating trust in the individual experiencing homelessness were experienced as expressions of caring (Biederman et al., 2013). A strong client-professional relationship in community services was described as the foundation of good quality care by persons experiencing homelessness in Asmoredjo et al.’s study (2017).

3.4 Review findings on ‘Structural and organisational aspects to meet needs’

Findings highlight that administration, lack of flexibility and location of services become barriers for seeking health- and social care. Integrated units that provide both health- and social care were suggested to facilitate access to professional interventions. The theme Structural and organisational aspects to meet needs is represented by two sub-themes: structural and organisational barriers and organisation to meet multi-faceted needs.

Structural and organisational barriers included descriptions of health- and social care systems as bureaucratic and disconnected from each other (Bungay, 2013; Corrigan et al., 2015; van Laere et al., 2009; Martins, 2008; Rae & Rees, 2015; Voronka et al., 2014). Locations of services in areas that were difficult to reach (Kertesz et al., 2014; McLeod & Walsh, 2014; Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Rae & Rees, 2015), inconvenient clinic hours (Kertesz et al., 2014), overcrowded clinics (Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009) and refusing care due to mistrust of staff and available services (Kryda & Compton, 2009; McLeod & Walsh, 2014) were also described. Persons experiencing homelessness described that available social services were based on middle class expectations, and not suited for the and long-term solutions to challenges of experiencing homelessness were wanted (Kryda & Compton, 2009). Furthermore, care was experienced as having a biomedical focus (Voronka et al., 2014). Despite a system of universal health insurance in Canada, access to healthcare remains a challenge for women with children, younger adults and victims of violence experiencing homelessness (Hwang et al., 2010). Examples of non-financial barriers to healthcare were lack of a primary care provider, not having health insurance due to being a refugee or recent migrant, and that the health insurance card was lost or stolen. One survey concludes that organisations working with persons experiencing homelessness need to focus on results of social services (Asmoredjo et al., 2017). Persons experiencing homelessness were satisfied with the relationship with the social services personnel, but highlighted that the intended results, like reintegration and participation in society, were not achieved.

Organisation to meet multi-faceted needs were drop-in services, integrating primary and behavioural care, reminder calls for appointments (Jenkins & Parylo, 2011) and peer navigators with lived experience of homelessness (Corrigan et al., 2015; Kryda & Compton, 2009). Persons experiencing homelessness wished for more flexible health- and social services (Corrigan et al., 2015; Jenkins & Parylo, 2011; van Laere et al., 2009), for example, a mobile health unit combined with basic supplies, like socks and deodorant, was appreciated (Whelan et al., 2010). Combining medical care with psychosocial support and practical assistance was experienced as helpful (Biederman et al., 2013; Voronka et al., 2014).

In addition, respite care after surgery, extended hospital stays or other housing options were suggested to reduce uncertainty and stress (Biederman et al., 2014). Persons experiencing homelessness described that increased social service utilisation at shelters (McLeod & Walsh, 2014), keeping families together, good schools for children (Gültekin et al., 2014), and education and job training were important aspects to help facilitate the transition from homeless to home (Gültekin et al., 2014; Voronka et al., 2014).

4 DISCUSSION

The synthesis of qualitative and quantitative findings from 22 studies provides a comprehensive compilation of expressed needs of health- and social care, as well as experienced barriers and facilitators for seeking care, of persons experiencing homelessness. Including perspectives from individuals’ experiencing homelessness in research, ultimately provides ground and potential for a more complex, holistic and interrelated analysis, that can be used to for guidance in systematically addressing health inequities. This is well aligned with the UN Agenda 2030 (2015) to promote prosperity and address a range of social needs, while protecting the planet and working for sustainability. Two of the 17 stipulated goals in the Sustainable Development Agenda (SDG) can be discussed in the light of the findings of this review: goal three, good health and well-being and goal 10, reduced inequality. These are especially relevant as goal three resonates with the mission of health- and social care, and goal 10 to our findings of contrary experiences, and experiences of inequality, with regards to health- and social care delivery.

4.1 SDG goal 3: good health and well-being

The theme Unmet human needs contributes to the mounting evidence of the extent to which social and economic disadvantages lead to huge health inequities (Aldridge et al., 2018; van Dongen et al., 2019; Fazel et al., 2014). In the specialism of inclusion health, responding to the burden of disease stemming from social deprivation requires professional services beyond those traditionally recognised, for example implementing the delivery of overlapping health- and social services (Luchenski et al., 2017). Consequently, in line with the inclusion health report from the Cabinet Office and UK (2010), findings of this review underline the importance of infra-structure in health- and social care, and collaboration between professionals and across disciplines, to capitalise on the synergies between medical, nursing and social models of care.

Results from this review corroborate that living without a shelter of a home compromises health- and social well-being. Providing stable housing has been identified as number one priority among socially excluded populations (Luchenski et al., 2017), and housing first programs for people who are homeless are expanding rapidly in Europe and in the USA (Nelson, Sylvestre, Aubry, George, & Trainor, 2007). A recent review (Ly & Latimer, 2015) concludes that these programs, that is, combining access to permanent housing with community-based, integrated treatment, rehabilitation, and support, decrease shelter and emergency department costs. Impact on hospitalisation and justice costs remains ambiguous. Housing first programs are examples of interventions aimed at improving health- and social outcomes among vulnerable groups in society. However, the combination of health- and social components in such programs make evaluating cost-effectiveness difficult. Thus, using traditional economic measures, that is, Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYS), may be unfair as it would understate the value of improving the quality of peoples’ lives over and above their health (Chisholm, Healey, & Knapp, 1997; Ly & Latimer, 2015). We found no studies that described both cost-effectiveness and needs of health- and social care in persons experiencing homelessness.

When interpreting the results from this systematic integrative review it is important to bear in mind that 50% of the included studies were conducted in the USA, a nation without a healthcare system that provides equal quality access for all citizens (Pant, Burgan, Battistini, Cibotto, & Guemara, 2017). Consequently, high rates of unmet dental- and healthcare needs were reported in these studies. On the other hand, unmet needs were also reported in studies from countries with universal healthcare. Thus, our findings underscore that healthcare access remains a challenge for persons experiencing homelessness, irrespective of healthcare system. According to persons experiencing homelessness, possible strategies to reduce barriers for good health and well-being include societal support to accommodate basic human needs, supportive relations with professionals from health- and social care, and special programs that integrate health- and social care, including flexible, drop-in services. This review highlights the importance of outreach services, as persons experiencing homelessness describe lack of awareness of healthcare problems, in combination with not knowing where to seek help. The Sustainable Development Agenda emphasises partnership to reach the Agenda 2030 goals, and in line with the findings of this review and previous research (Aldridge et al., 2018; Fazel et al., 2014; Slockers et al., 2018), partnership is crucial to adequately address the existing inequalities in health and well-being for individuals experiencing homelessness.

4.2 SDG goal 10: reduced inequality

This systematic integrative review reports on experiences of interpersonal barriers, for example, being stigmatised and discriminated, as well as facing structural and organisational barriers when persons experiencing homelessness seek health- and social care. These examples of inequalities resonate with the aim of goal 10, reducing inequality. Thus, removal of barriers to access and uptake of health- and social services is imperative, and removal of barriers can be accelerated by involving people who have experience of social exclusion (Luchenski et al., 2017). In three included studies, peer interviewing was utilised to give voice to physical and social needs in persons experiencing homelessness (Corrigan et al., 2015; Gültekin et al., 2014; Voronka et al., 2014). A feasible next step toward reducing barriers and inequality, is using participatory methods, like group brainstorming, case studies, participatory mapping, transect walks and analyses of lived experiences (Chambers, 1994), to create relevant and acceptable interventions to target these experienced health inequities. However, marginalised groups, like persons experiencing homelessness, outside of mainstream society have been systematically excluded from national and international policy making forums (Siddiqui, 2014). Patient and public involvement (PPI) has been introduced as a commitment to empower individuals and communities to have a greater impact over healthcare research, healthcare priorities and organisations (Entwistle, Renfrew, Yearley, Forrester, & Lamont, 1998; INVOLVE, 2012). Involving persons with experience of homelessness in PPI activities may produce beneficial solutions for both persons experiencing homelessness and diverse societies.

Findings related to the theme Interpersonal dimensions of access to care, underline that professional encounters and relationships play an important role during times of homelessness and isolation. In the literature, compassion and authentic presence is emphasised in caring for patients, irrespective of care context (Watson & Smith, 2002). The experienced inequalities in health and well-being may be countered by the basic concept of caring and showing respect in individual meetings (Nelson et al., 2008). An example of initiatives toward this end are the socially accountable health professional education (SAHPE) schools created worldwide to achieve health equity, through transforming healthcare professional education to meet local needs (Preston, Larkins, Taylor, & Judd, 2016; Reeve et al., 2017). This entails working in partnership with communities to provide health services that meet community needs, and to undertake research that is responsive to community priorities. Initiatives aiming at transforming education to target health- and social inequities also stress the importance of preparing students for the realities of teamwork (Frenk et al., 2010). The literature suggests that health students of SAHPE schools are more likely to stay in rural areas and serve disadvantaged communities (Reeve et al., 2017). Furthermore, these students are more effective in meeting the needs of vulnerable populations, such as persons experiencing homelessness. To favour collaborative relationships in effective teams, professional silos and hierarchies need to be deconstructed (Frenk et al., 2010). Findings of a previous literature review highlights that the diversity of clinical expertise in healthcare teams has potential both to improve patient care and effectiveness of the organisation (Lemieux-Charles & McGuire, 2006). Emphasising shared vision, a collective orientation and constructive communication in the team may help strengthen teams and teamwork (Klarare, Hansson, Fossum, Furst, & Lundh Hagelin, 2018), consequently providing provisional hands-on suggestions for improved collaboration among health- and social care professionals to meet needs of persons experiencing homelessness.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic integrative review to explore experiences of health- and social care in persons experiencing homelessness. To capture the information needed to answer the research questions, we performed a broad search and included both quantitative and qualitative studies in the analysis. We strictly adhered to recommendations for undertaking a systematic integrative review, carefully considering each step in the research process (CASP, 2018; CDR, 2009; Harbour & Miller, 2001; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The research team included researchers with extensive experience of evaluating quality of both qualitative and quantitative research reports. However, assembling findings from studies, qualitative and quantitative, invariably involved a degree of subjectivity and interpretation. In qualitative research, the findings are typically supported by verbatim examples; therefore, readers are also recommended to consult the original works. Furthermore, the findings from the original studies may be diminished when only findings of relevance for the reviews aim are selected. As with all evidence synthesis, this review is limited to the quality of the included studies. In addition, although a wide range of keywords was used, it is possible that all eligible studies were not identified.

All but one of the studies reviewed were carried out in so called ‘developed’ countries (USA, Western Europe), thereby limiting the generalisability of our findings. Furthermore, our search was limited to adult populations, and further work to investigate health experiences of youth experiencing homelessness is needed. There is also a need to further study the subgroups of older adults’ needs of healthcare since the demographics of the homeless population have shifted from mainly comprising young adults to an increasing number of older adults (Brown, Kiely, Bharel, & Mitchell, 2013). In addition, our keywords did not specifically target articles reporting on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer adults who experience homelessness, even though using the term homelessness in the searches may have been sufficient. However, the literature suggests that transgender and gender non-conforming adults who experience homelessness encounter several unique challenges in the health- and social care system, particularly with regard to safety and gender-affirming support (Ecker, Aubry, & Sylvestre, 2019).

Studies involving veterans experiencing homelessness were excluded as veterans constitute a unique segment of the US population that differs from other homeless populations (Rosenheck, Leda, Frisman, & Lam, 1996). Due to their services, veterans have special benefits such as free healthcare, disability and education benefits, and home-loan guarantees. In addition, veterans may be more vulnerable to certain health, social, and psychological problems due to exposure to combat-related trauma and geographic dislocation for military deployment (Perl, 2011). Despite the mentioned methodological shortcomings, we believe that this systematic integrative review gives an overall picture of experiences and needs of health- and social care of persons experiencing homelessness.

4.4 Implications of the findings and conclusions

Complex needs of health- and social care require flexible solutions for persons experiencing homelessness. Hypotheses grounded in personal experiences, as expressed by persons having experiences of homelessness, can be put forward to inform further research and help shape practice. Examples of tentative hypotheses, based on the results of this review, are (a) Persons experiencing homelessness neglect seeking health- and social care since priorities related to basic human needs (food, shelter, security) take precedence, and (b) Encounters and relationships with health- and social care professionals are important during times of homelessness, since the need for personal support is increased, while the social network is reduced. Designing and providing team based, multi-professional interventions in collaboration with persons experiencing homelessness, involving flexible and engaged health- and social care professionals, is also in demand.