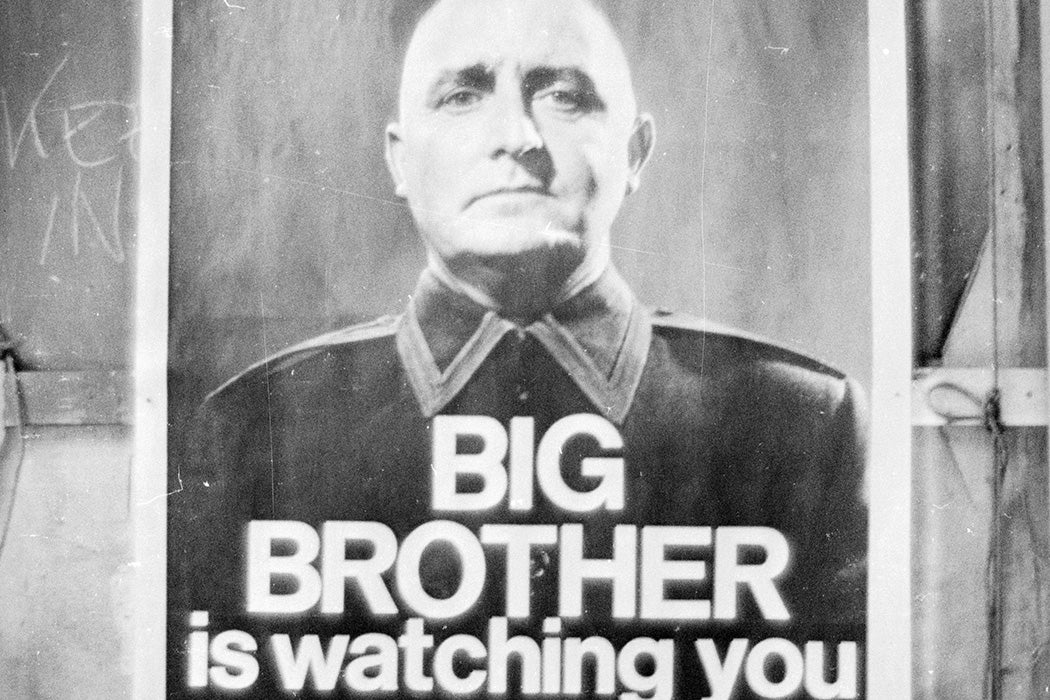

By 2020, “more countries had been classified as authoritarian regimes (‘autocracies’) than were transitioning to democracy,” writes political scientist Julian G. Waller, citing data from V-Dem, the Swedish research center that studies the varieties of democracy. So, is democracy on the ropes in the aftermath of post-Cold War American hegemony?

“The age of democratization has plausibly ended; or, perhaps better framed, the edge and middle cases had all ended up failing to institutionalize the democratization process of the 1980s and 1990s,” writes Waller.

Meanwhile, nationalist and/or populist movements have gained power in the more established democracies, in some cases initiating authoritarian processes to solidify their power.

“The global state system is in crisis,” continues Waller. But is this an age of authoritarianism? Is there an authoritarian wave swamping the planet? And what, exactly, are we talking about when we talk about authoritarianism?

At its most basic level, explains Waller, “political authoritarianism denotes a political regime that is not an electoral democracy.” This of course requires a definition of electoral democracy, which may not be as self-evident as it used to be, but Waller suggests that “the apex of decision-making political offices are chosen through a competitive struggle for the people’s vote through partisan elections under broad suffrage in which the electoral outcomes are uncertain” as a guide. Electoral democracies are unique in their “orientation to political power, to elite rotation, to leadership succession, and to mass participation in the political process and accountability mechanisms.” Paradoxically, electoral democracies can vote in authoritarians.

More to Explore

Is the Authoritarian Personality a Legitimate Concept?

Those regimes lacking the characteristics of electoral democracies cover a wide gamut across space and time. Waller includes in this list

[m]ilitary juntas, absolute monarchies, personalist dictatorships, ideocratic party-states, bureaucratic-corporatist states, theocracies, and electoralist non-democracies all fall under this capacious concept, united in their orientation towards power (top-down) and their unaccountability to the wider population.

There’s a lot of variety here. Some of these, of course, include elections—fixed, fraudulent, controlled. In some cases, strongmen crave popular support, so the popular will can sustains autocratic stability. And some dictators need their egos stroked with high turnouts and overwhelming electoral wins. Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov, who died in 2006, claimed to win his 1992 election with 99.5 percent of the votes cast for him.

“There are certainly authoritarian regimes or illiberal ideological pressures that act on the world system, sometimes in patterned ways,” Waller writes. “But whether they do so with intentional-agential purpose, in concert, or in tandem is not always clear.”

Weekly Newsletter

Other political scientists have come up with the term “black knight” states, which Waller defines as “strong, hegemonic authoritarian regimes whose international influence has enabled and furthered this trend towards autocratization and ‘democratic backsliding.’” China, Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela are among the states typically named as such bad actors, particular when striking out against dissidents who have fled abroad.

But Waller thinks we should be “particularly cautious in assuming the existence of ‘authoritarian internationals,’” a coordinating nexus of authoritarians on the model of the old centralized Communist International, which was controlled by the Soviet dictatorship. This isn’t to say that there are no mutual learning and/or alliances among thugs: China and North Korea, for instance, have aided Russia’s war on Ukraine. Waller argues that for now such states are primarily focused internally; they’re authoritarian for local reasons—and domestic repression is a full-time job.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.