We thought we were slowing the chemical pollution crisis by swapping our bleach for non-toxic cleaning alternatives and ensuring our beauty products only have naturally derived ingredients. Yet, studies demonstrate that green cleaning products and common sustainable swaps still contain ingredients that are harmful to human life.

Browsing the web or walking down the aisle of any major grocery store, you’ll find trendy household and cosmetic products labelled “natural,” “green,” or “safe for our oceans.” Maybe you let out a sigh of relief: you’re reassured by the leaf on the label, a “1% for the Planet” designation, or a PETA certification that relieves you of the planetary impact your consumption may cause. Nonetheless, there might be significant cause for concern for your and your family’s health following the purchase. There’s been little continuous study of regular exposure to these products and little regulatory oversight of hazardous chemical usage in common household products in the United States.

As Community Health Nurse, Merri Lynne Bunge, warned us almost five decades ago, the use of new chemicals in the home has expanded rapidly. From the bleach and Drāno that ensure spotless bathrooms to the formaldehyde found in almost one-fifth of all cosmetic products, our exposure to potentially harmful substances is widespread. To meet that moment, the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) was passed in 1976, regulating more than 80,000 chemicals and their usage through the Food and Drug Administration. Yet, the TSCA allowed for more than “60,000 chemicals that were on the market to continue being used without additional safety protections,” writes Elizabeth Grossman. Unlike pharmaceuticals, which undergo rigorous testing, chemicals in cleaning and beauty products often lack comprehensive toxicity data. Scientist John Warner, former president of the Warner Babcock Institute for Green Chemistry, offers solutions to counteract this: he advocates for an assay-based system that assesses chemical hazards based on their inherent attributes rather than individual chemical components, Grossman explains. While some states, including California, require greater protections from hazardous chemicals, federal oversight, particularly under administrations that ignore scientific data, remains precarious.

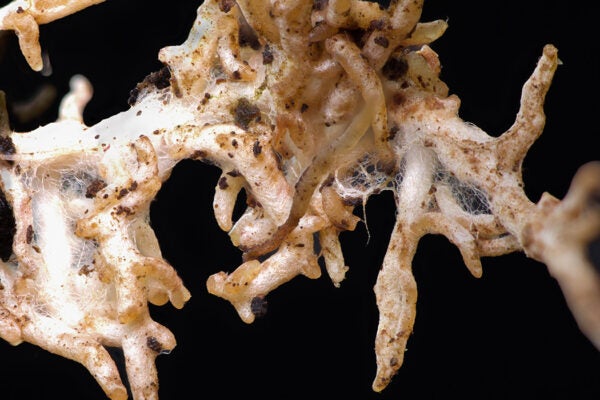

The lure of natural products under this paradigm is quite convincing. But that non-toxic surface cleaner isn’t exactly harmless. One key issue with so-called “green” products is their use of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which easily vaporize at room temperature and can create dangerous indoor pollutants. According to the American Lung Association, even naturally derived fragrances—like the citrus oils in many cleaning sprays—can react with other household chemicals, forming harmful air pollutants. The result? VOCs that contribute to respiratory problems, allergic reactions, and headaches.

More to Explore

How Government Helped Birth the Advertising Industry

Endocrine disruption is another major issue lurking in household products, including those marketed as safe or sustainable. These chemicals interfere with hormone function, potentially leading to reproductive issues, metabolic disorders, and even certain cancers. A recent study from the National Institute of Health highlights concerns about consistent exposure to essential oils—particularly lavender and tea tree oil—among teenagers. Despite their reputation as gentle, natural remedies, these oils have been linked to hormone disruption, raising questions about their long-term safety.

Weekly Newsletter

If regulatory oversight remains limited and companies continue to market misleading “green” products, what can consumers do? Reading through ingredients lists is a start. Some scholars advocate for a degrowth approach—slowing consumption rather than simply swapping one product for another. Where can the simple, yet effective, white vinegar and baking soda combination replace bleach? This systemic shift would require moving beyond the “sustainable” branding of consumer culture and prioritizing products that are truly non-toxic, biodegradable, and safe.

The presence of a leaf on a label or a “natural” claim doesn’t guarantee safety for human health or the environment. While regulatory policies such as the TCSA attempted to address chemical risks, significant gaps remain. To reduce exposure to harmful substances, producers must look beyond greenwashing and advocate for systemic change—whether through stricter regulations, scientific advancements in hazard assessment, or the revival of traditional, non-toxic alternatives. Until then, it remains up to consumers to critically assess the products they bring into their homes and onto their bodies.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.