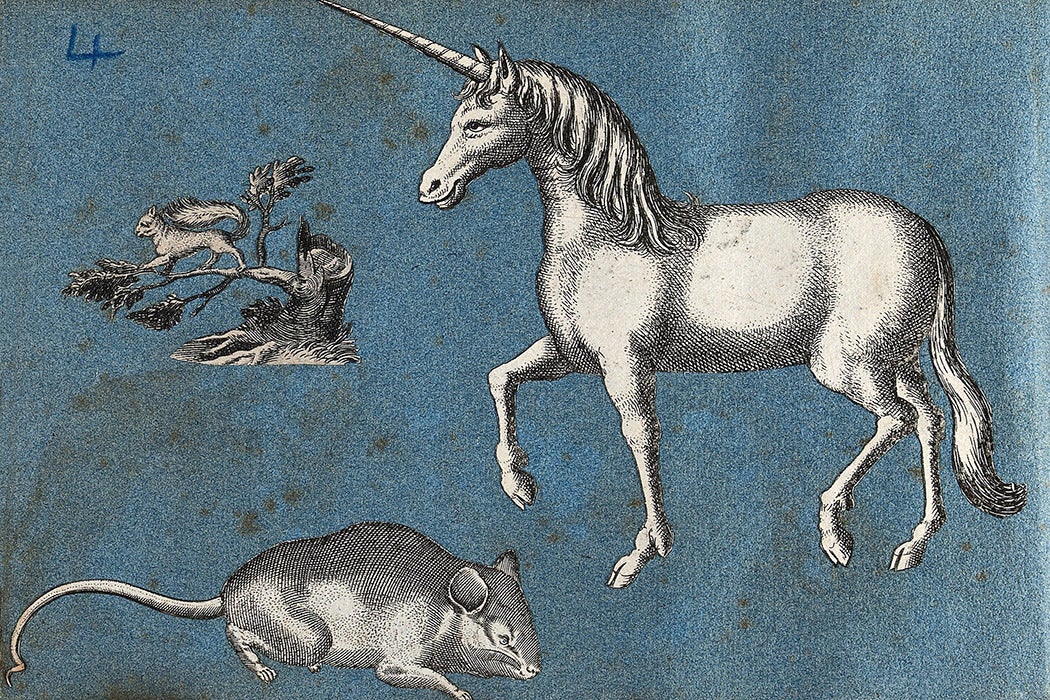

In a trailer for the 2017 Frederick Wiseman documentary about the New York Public Library, a telephone reference librarian is seen gently informing a caller, “a unicorn, ahhh, is actually an imaginary animal.” Yet, in addition to being imaginary, unicorns also seem to be undying, a “species” that can’t go extinct.

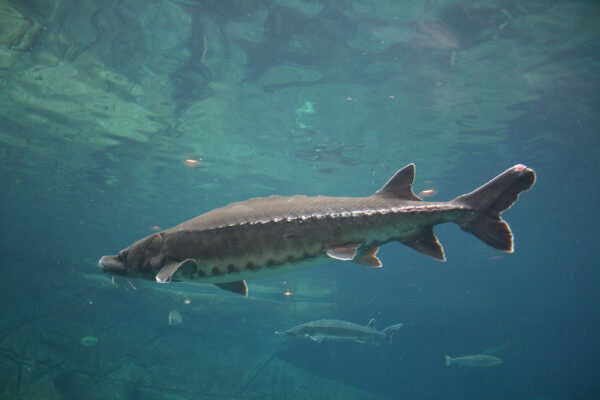

Unicorns may have evolved into the “ultimate symbol of irrationality and credulity,” writes historian E. C. Spary, but up into the early 1700s, they were still considered plausible by the learned of Europe. If the narwhal tusk, a tightly spiraling tooth than can grow up to nine feet in length, was not in fact from a unicorn, then perhaps the horn of the southern African wildebeest or gnu was what the ancients meant by a unicorn—never mind that these are actually two-horned.

“The unicorn has long featured in histories of early modern natural history as the very opposite of enlightenment,” Spary writes. “The progress of scientific knowledge, it is argued, led to the exposure of the unicorn as a creature of pure imagination, gladly relinquished by naturalists in the age of reason.”

But unicorn horns lingered on in both the imagination and in the material sense, right there on display in the collections and cabinets of curiosities, or Wunderkammer, that were one of the private precursors of natural history museums. The problem of what to do with these alleged unicorn horns began to present itself as their identification came into question.

Unicorn horns, “linked to purity, magic, healing, and power,” persisted in Wunderkammer well into the eighteenth century. The unicorn itself, however, became less and less likely as various horns, tusks, and antlers in such collections were more accurately attributed to verifiable species like narwhals, rhinos, gnus, and other species. What role then, asks Spary, could a mythical animal “continue to possess in collections even after its existence had come to be queried”?

“The debunking of unicorns as an ontological category did not prevent their horns from remaining desirable adjuncts to enlightened cabinets,” Spary writes, “even if they declined in financial value and changed in significance. They now became a symbol, not of extreme rarity, but rather of the program of putting the world to rights for which the collection stood.”

More to Explore

The Hunt of the Unicorn Tapestries Depict a “Virgin-Capture Legend”

The horns, Spary continues, began to stand “for all the illusions that the progress of reason would correct. That is, they represented the power of enlightenment.”

Horns thus came to “serve as a focal point for story-telling about how enlightened collecting dispelled the obscurity that had reigned over earlier knowledge.” Can you believe people used to think that this porpoise’s tooth grew out of the head of a magical goat that could only be captured by a virgin? Or that whales used to be thought of as fish?

The narwhal’s long protruding canine tooth could be attached to a stuffed horse’s head, but divorced from the mythological and chimerical, it was still a rare marvel in its own right. It may have been purchased as a unicorn horn, but it came to be marked instead as one of the wonders of the Arctic. Few then (few today!) ever saw a narwhal in the blubbery flesh, which made them almost as rare as unicorns.

Spary notes that many of the things that used to be called unicorn horns are buried away in collections today, “or else they merit an indulgent nod to past credulity.” To be fair, most of the contents of museums aren’t on display, but some particularly odd narwhal remnants do have pride of place. London’s Museum of Natural History has a rare two-horned example and one horn from a narwhal that wandered as far south as the river Thames.

Weekly Newsletter

The skull of another two-horned narwhal that was killed in 1684 is on display today the old whaling port of Hamburg, Germany. It’s said to be the only known example of a female narwhal with two tusks.

“During World War II, it was the only one of the collection’s specimens to be saved from a devastating fire,” writes Spary. Metaphorically, that seems to make it something of…a unicorn.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.