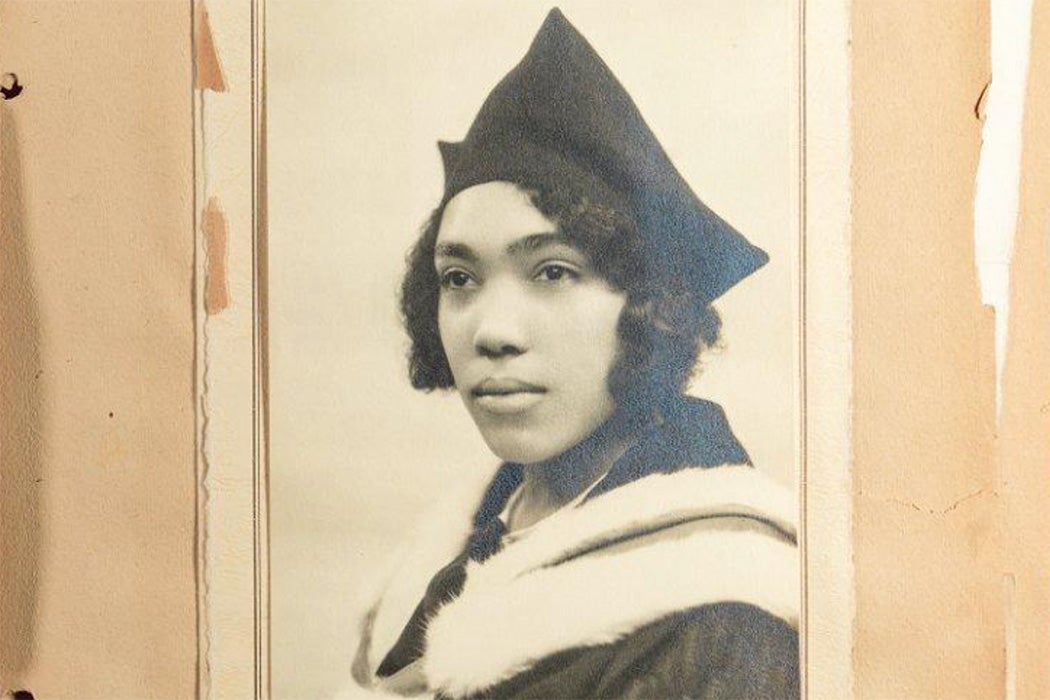

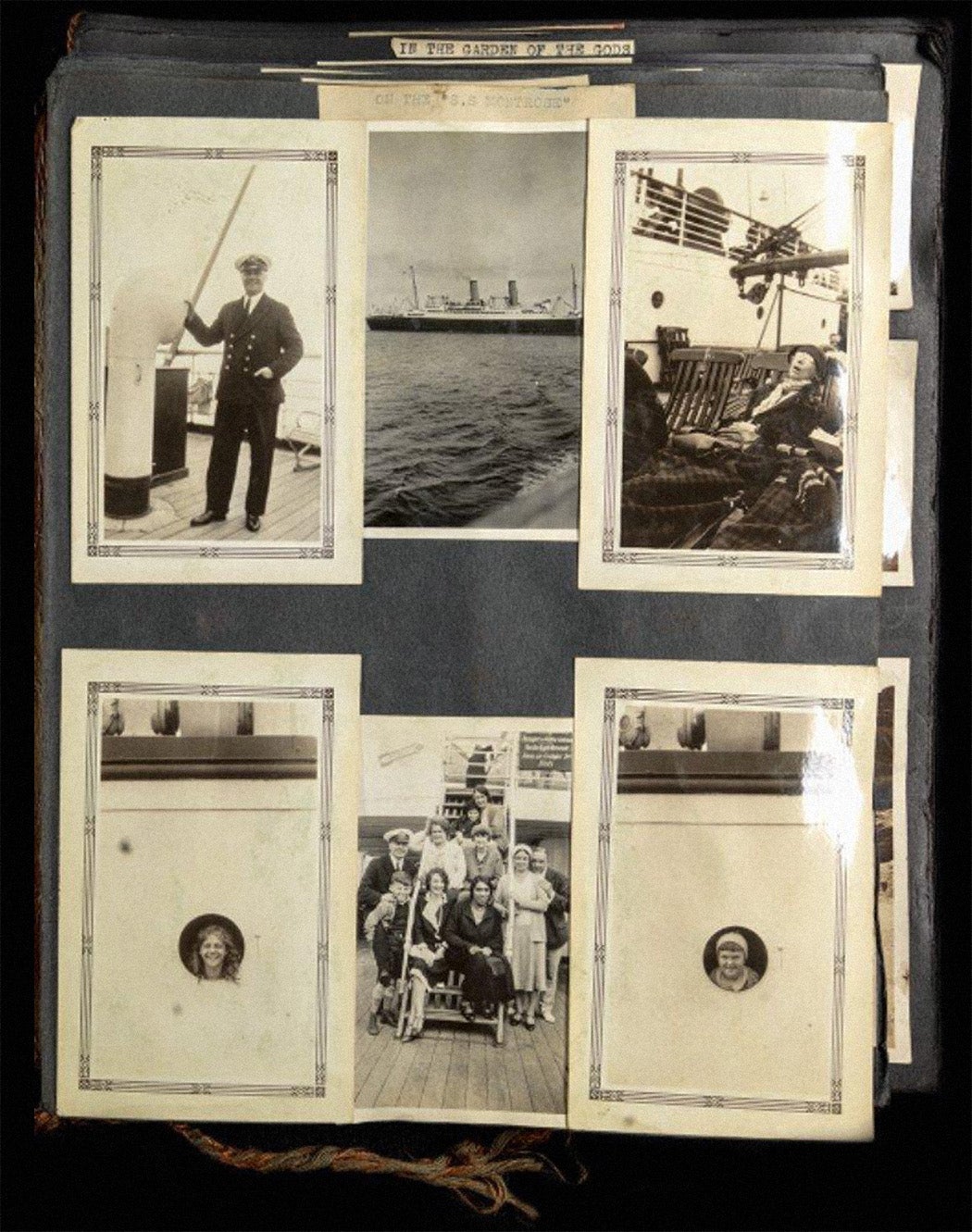

The first photos in Merze Tate’s album from the summer of 1931 are a collection of joyful, silly images taken aboard the SS Montrose en route from Montreal to Cherbourg, France. Tate beams from the center of a group of travelers gathered on deck, all strangers to her when she boarded the ship. The twenty-six-year-old Indianapolis high school teacher had undertaken her first international trip alone, but she had a gift for making connections, often over a bridge table. It was a skill that would serve the ambitious academic and avid traveler well throughout her lifetime; she would often find, as she did frequently that summer in France, that she was the only Black woman in the room.

Tate’s entire life journey is a notable one. Born in rural Michigan in 1905, she was one of the first Black women to earn a degree from Western State Normal School. She then earned a graduate degree from Columbia University, and in 1931, she studied French history at the Sorbonne. She would become the first Black woman to earn a PhD in government at Harvard and spent thirty-five years as a professor at Howard University, blazing a path for other Black women in academia.

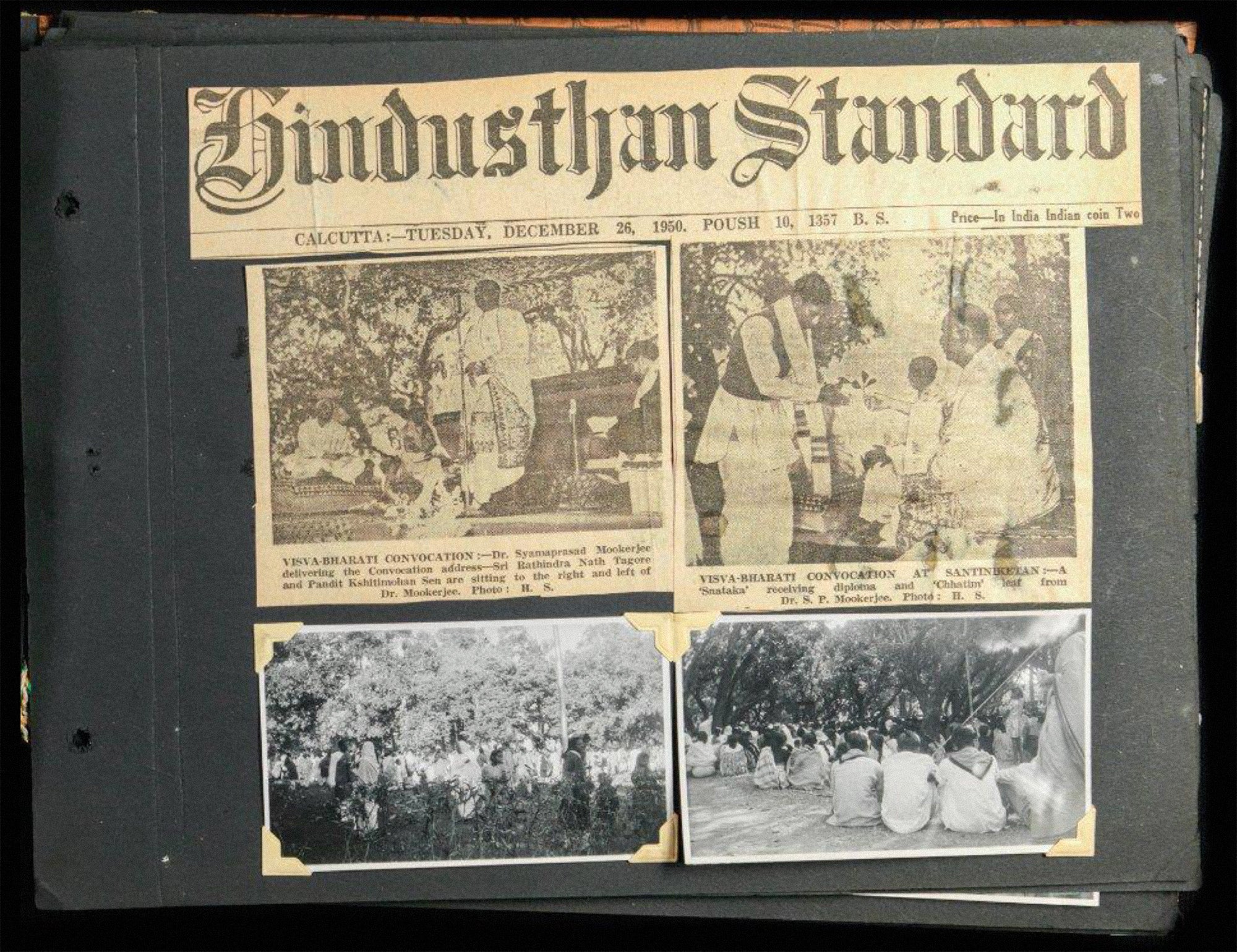

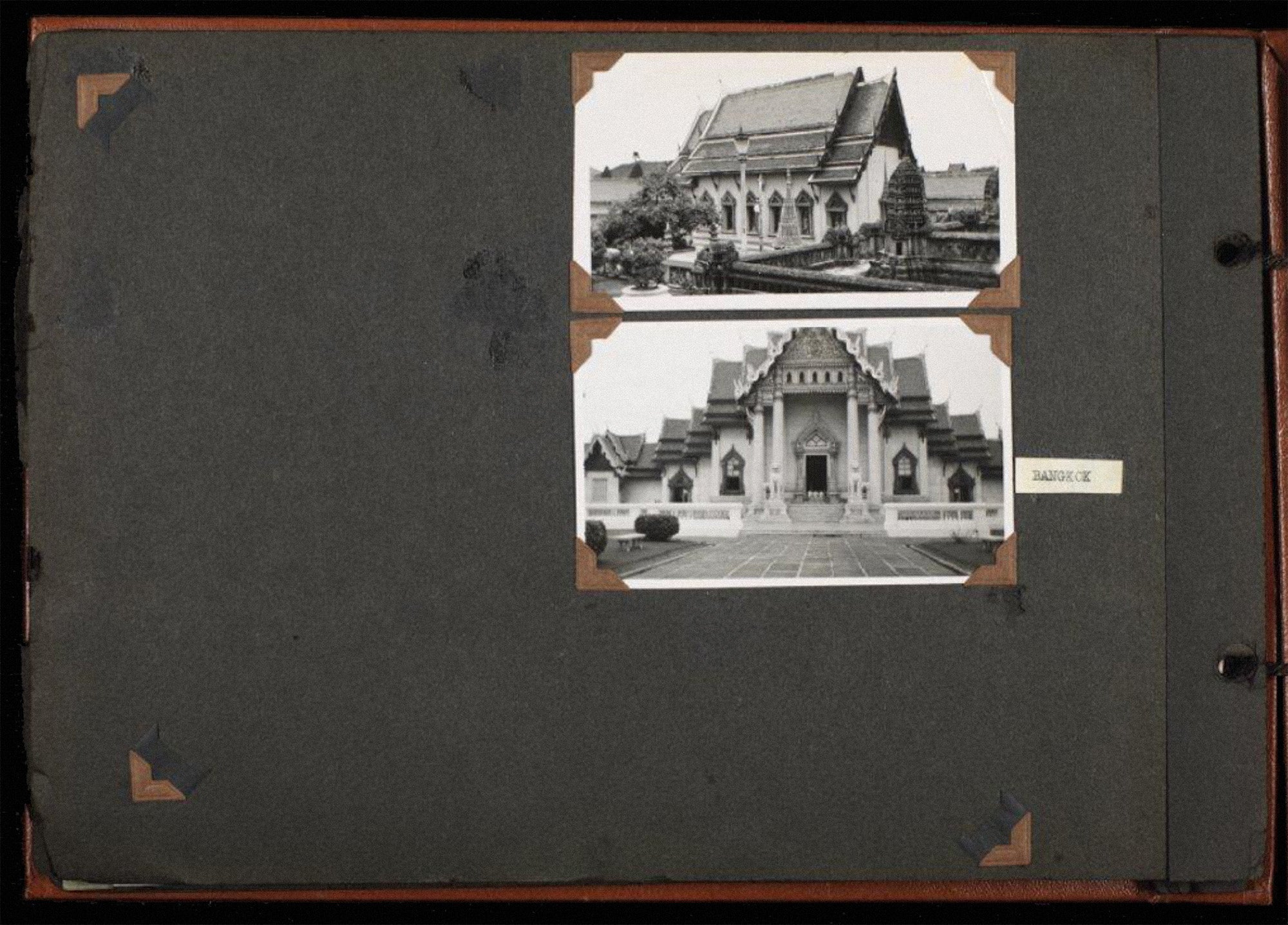

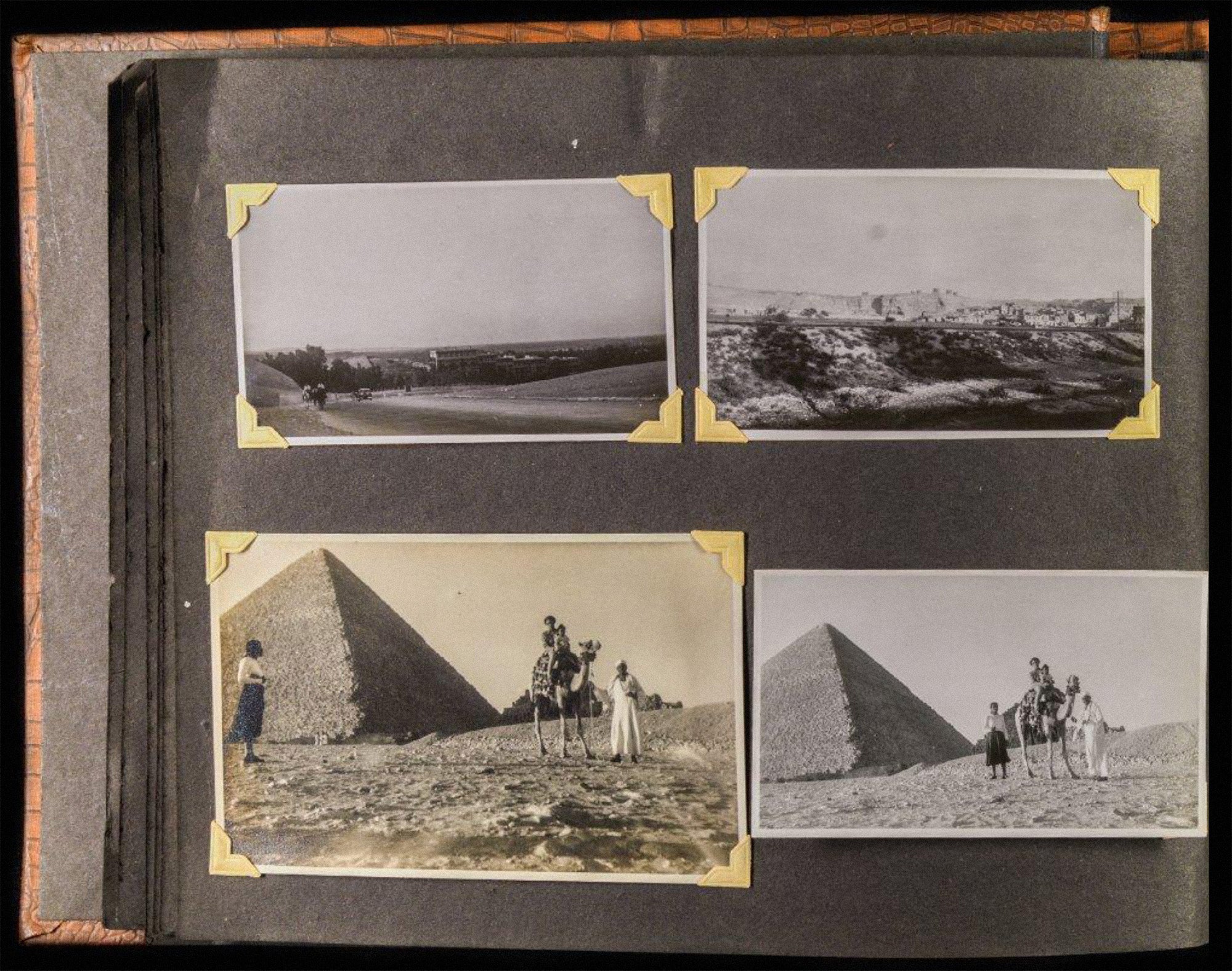

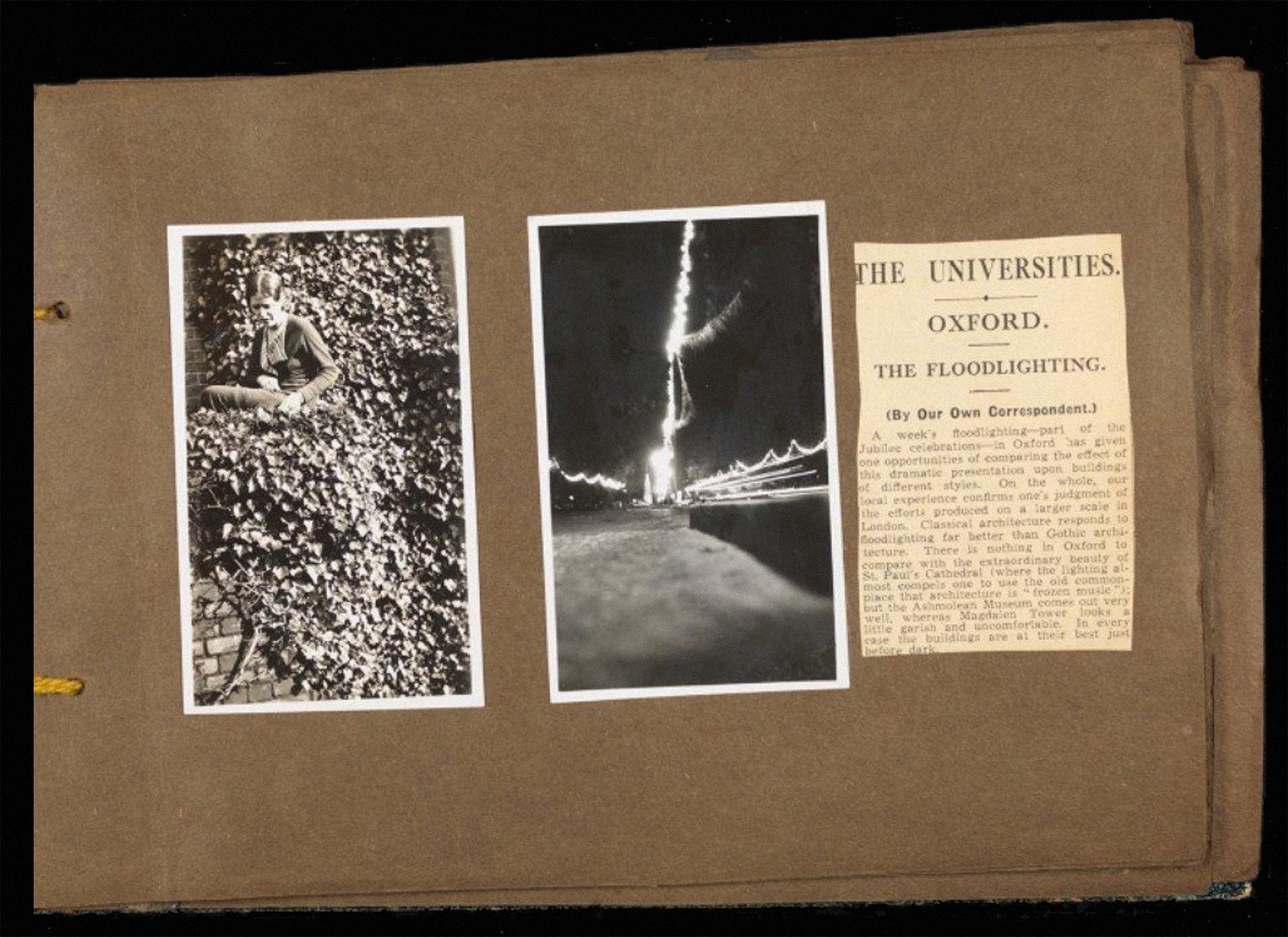

Tate, who passed away in 1996 at the age of ninety-one, is also one of the few Black women of the era to leave an extensive archive, including a dozen photo albums and scrapbooks shared via JSTOR by Tate’s undergraduate alma mater, now known as Western Michigan University. In these pages, Tate cataloged her first decades of international travel through India, where she was a Fulbright scholar, Southeast Asia, and Egypt.

Globetrotting is only part of Tate’s story, but it’s an important one, says historian Barbara Savage who wrote the first biography of Tate, Merze Tate: The Global Odyssey of a Black Woman Scholar, published in 2023. Savage found it a challenge to make sense of Tate’s “obsessive need to travel and explore.”

“The power of that desire and her need to meet it remains a central and sometimes enigmatic feature of her long life,” Savage writes. She sees the earliest evidence of Tate’s fascination with exploration in her childhood love of maps and travelogues. Tate would ultimately visit five continents and travel around the world twice, her historical work on race and imperialism informing her travels and her travels informing her groundbreaking work.

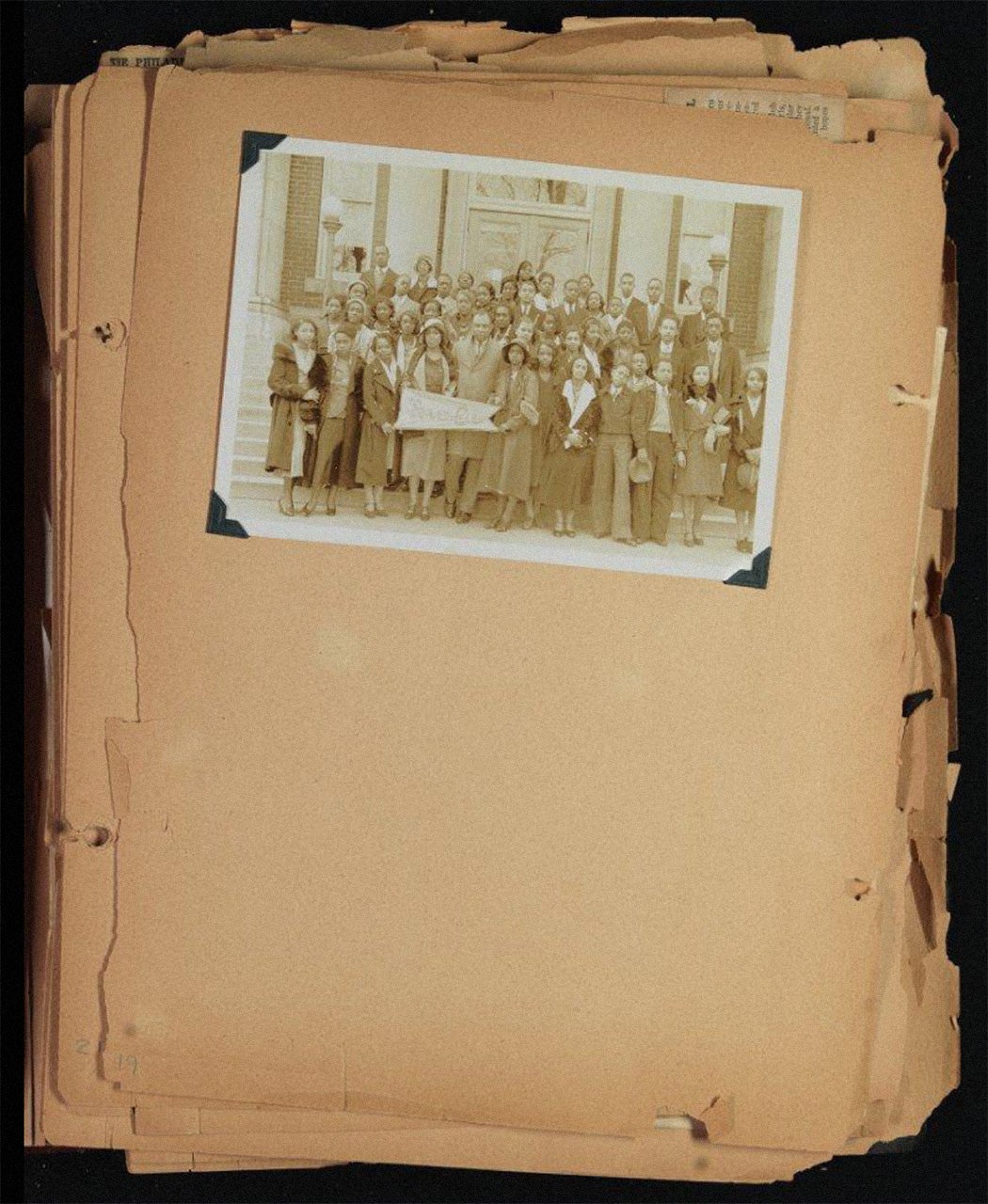

But Tate was never content to travel solely for her own benefit. She wanted to share the world that so fascinated her. In the spring of 1931, as she anticipated her first trip to Europe, she formed the Travel Club for the students of Crispus Attucks High School, an all-Black school in segregated Indianapolis. Over the course of a year, Tate oversaw fundraisers and solicited donations to pay for a trip to Washington, DC—a total of more than $2,500. Among the events was a public lecture Tate delivered on her travels through Europe, illustrated with her photographs.

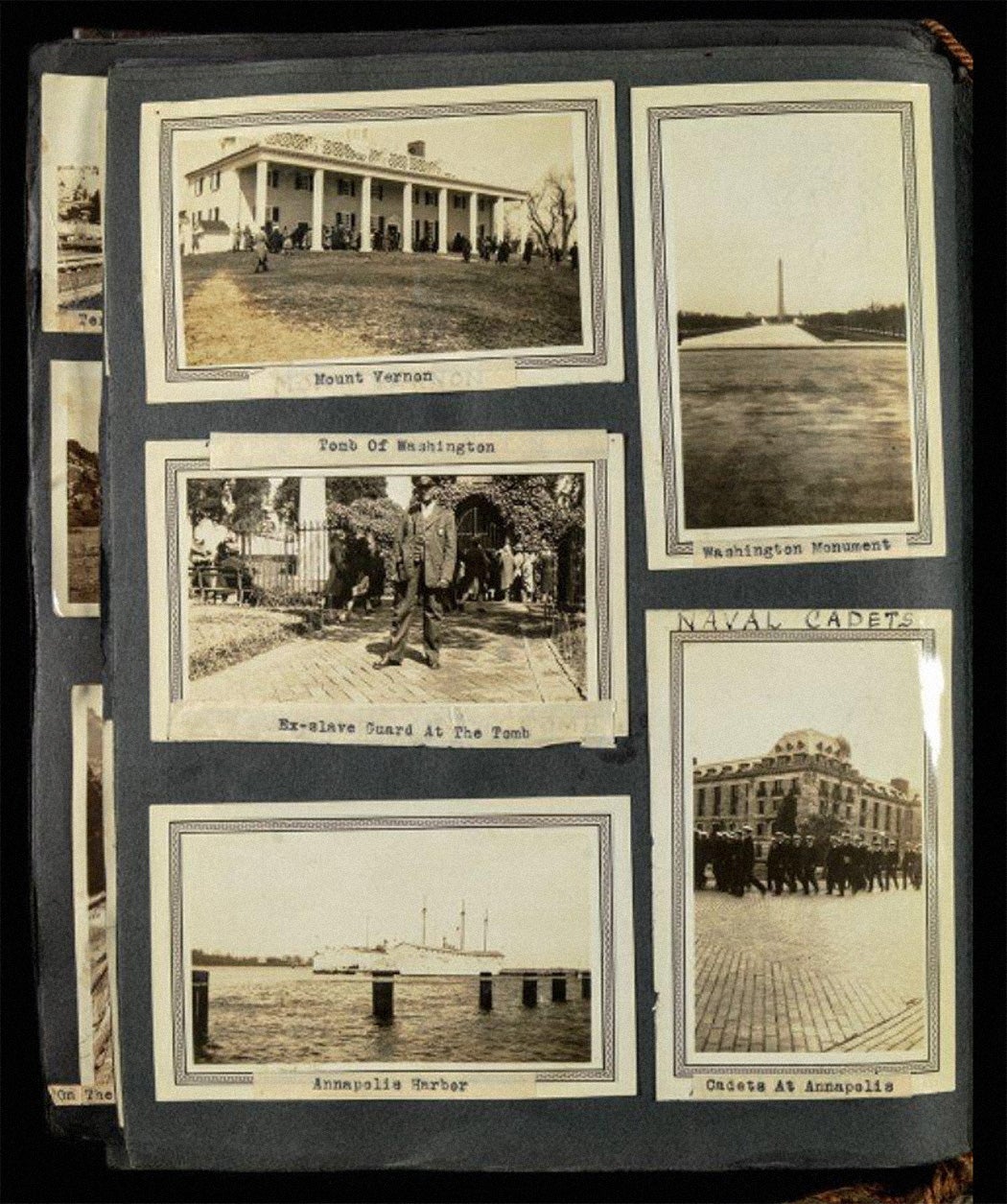

When the Travel Club set off in March of 1932 on a nineteen-hour train ride from Indianapolis to the nation’s capital, Tate again brought along her camera. The forty-three students in Tate’s charge visited all the city’s major sites, plus some often overlooked on school trips organized by white teachers: Frederick Douglass’s house, Miner Teachers College, and the Howard University campus that would later become Tate’s academic home. In the same photo album that features Tate’s Europe trip are photos of the Lincoln Memorial, Arlington Cemetery, and Mount Vernon. Tate carefully captioned an image of a Black man in uniform at George Washington’s burial site at Mount Vernon: “Ex-slave guard at the tomb.”

In another scrapbook, Tate saved a group photo of the Travel Club, proudly unfurling their club flag, and newspaper clippings about the trip, including a letter she wrote to the Indianapolis Recorder. Under the headline “Should Colored Children Travel?” Tate argues not her self-evident belief that travel is beneficial to the individual, but that by traveling, the children had become ambassadors of sorts: “White and colored alike marveled at the splendid conduct of the group,” she wrote.

Before the cherry blossoms emerged in the spring of 1933, Tate was off on another adventure, this time to the University of Oxford; in 1935, she became the first Black American to earn a graduate degree there. But the legacy of Tate’s short-lived high school travel club lives on today in Kalamazoo, Michigan, where she earned her teaching degree. Inspired by Tate’s story, journalist Sonya Bernard-Hollins founded the group now known as the Merze Tate Explorers with the goal of introducing Michigan children to Tate’s expansive view of life’s possibilities and to all the places she visited in her lifetime.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.