Long after birds and mammals were shown to display remarkable cognitive abilities, reptiles continued to be seen as “cognitively inferior.” Turtles, squamates (scaled reptiles), tuatara, and crocodiles (including alligators and caimans) were stereotyped as slow and inflexible learners—much like their dinosaur ancestors were once characterized as big, lumbering, and brutish.

This was the result of human ignorance, faulty assumptions, and limited evidence, much of it anecdotal. Herpetologist Gilles De Meester and evolutionary ecologist Simon Baeckens write that, into the 1970s, researchers were dismissing reptiles as “reflex machines,” “intellectual dwarfs,” and creatures of “very small brain.” The latter description implies much—but those implications turn out to tell us more about researchers than the subjects of their studies.

The few earlier studies that seemed to confirm the dumb reptile stereotype had “inadequate and ecologically irrelevant experimental study designs, such as suboptimal room temperatures or insufficient reinforces,” write De Meester and Baeckens. For instance, food, which works well as a motivation for rodents and birds in cognitive tests, seems to have much less appeal to reptiles because of their low metabolic rate and irregular feeding habits. Snakes, as an example, may not want to eat for months after consuming large prey, so a new food source may not interest them at all.

More recent studies of cognitive skills in reptiles have taken place in “(semi-) natural setting[s], using outdoor enclosures or camera-trapping and radio-tracking in the wild.” Reptiles are now “stimulated to learn ecologically relevant behaviors, such as finding shelter from a predator attack or avoiding toxic prey.”

The result?

“Reptiles display a range of cognitive skills not inferior to those documented in birds and mammals. Reptiles exhibit fast and flexible learning, long-term memory, spontaneous problem-solving abilities, quantity discrimination, and even social learning,” De Meester and Baeckens write.

More to Explore

There’s Something About Lizard Blood

These aren’t your grandfather’s reptiles.

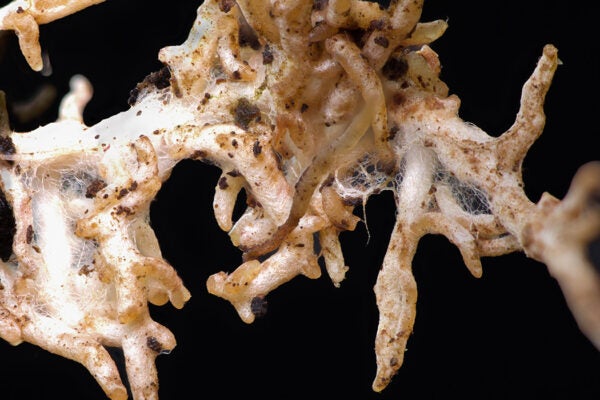

There’s even some evidence of reptilian tool-use: species of crocodiles and alligators “display sticks and twigs on their snout in order to lure nest-building birds.” This has only been observed in bird-breeding season, when the birds on the lookout for sticks to construct or repair their nests.

Once considered simple and “primitive,” the “reptilian brain is now recognized to govern complex behaviours,” write De Meester and Baeckens. They argue that reptiles show “immense potential” as model species for research into the “mechanisms, the development, and evolution of animal cognition.”

“Many biologists have lamented how the vast taxonomic bias of a select number of (mammalian and avian) species in animal cognition studies have severely impaired our understanding of its evolution,” they write.

Weekly Newsletter

Clearly, there’s a lot more to be learned about lizards, snakes, turtles, and crocs. As always when it comes to evolution, this also means discovering more about ourselves, for we share a common ancestry with reptiles. In fact, all vertebrate brains share the same basic ingredients, differing in the number and arrangements of neurons.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the concept of the “reptilian brain” as the foundation of a triune human brain system became so popular it still inflects the discourse even though neuroscience has moved well beyond that simplification. The human brain doesn’t have a “primitive” part at its base; there’s no lizard amygdala controlling our flight or fight reflexes. The idea, however, continues to have pull, likely because it’s so easy to understand—and provides a scapegoat, in the lizard-made-me-do-it excuse—than the actual complex interactions of brain networks.

And now we know that characterizing actual lizards and other reptiles as being primitive when it comes to cognition is another simplification.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.