What should a class about LGBTQ+ literature teach? When English professor John Pruitt began working on an independent study course on “the contemporary gay male American novel” in 2012, it led him on a quest to figure out what texts students interested in queer literature ought to read—and whether making a list like that even makes sense.

As early as 1971, Pruitt writes, some professors were offering classes on what historian Rictor Norton’s course termed “The Homosexual Literary Tradition.” Norton defined his project as a challenge to prejudice against gay people and their work.

During the 1980s, a conservative movement in higher education pushed the centrality of a canon promoting “Western” values. One reaction from the early gay and lesbian studies movement was developing queer readings of work by Shakespeare, Tennyson, and other pillars of the canon. Unlike Norton’s focus on the work of self-identified gay authors, this approach attempted to shake up the default to heteronormative understanding of literature. As queer theory scholar Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick put it, it’s possible to argue that “not only have there been a gay Socrates, Shakespeare and Proust, but that their names are Socrates, Shakespeare, and Proust.”

Pruitt notes that another purpose of LGBTQ+ literature courses is to serve the students who enroll in them as they try to make sense of their own identities. As literature scholar Ellen Louis Hart put it back in 1989, “for lesbians and gay men whose experience has been taboo, who have never had a consistent oral tradition on which to depend for information, literacy is fundamental to identity, culture, and survival.”

More to Explore

Gay Radicalism, Made in Kentucky

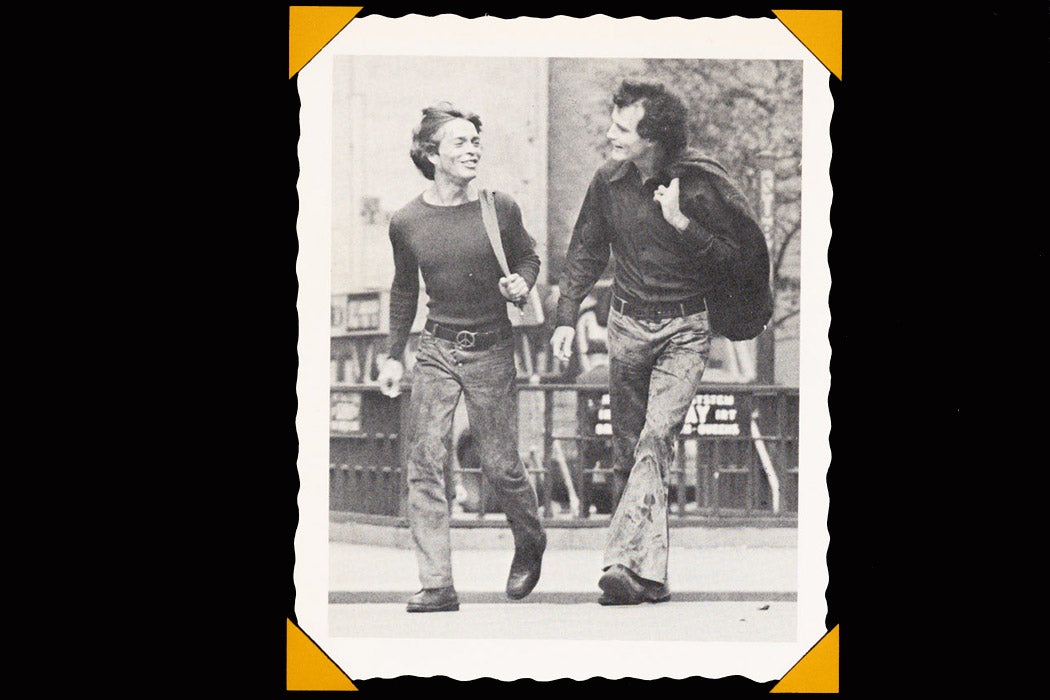

Both inside and outside academia, readers have strong opinions on books that are crucial to include in any “best of” list or canon. When a 1999 Top 100 list by a gay and lesbian publishing group failed to include Patricia Nell-Warren’s 1974 novel The Front Runner, many readers loudly objected, noting its influence on their own coming-out journeys. Others agreed with the judges and argued that it lacked the literary merit to make the list.

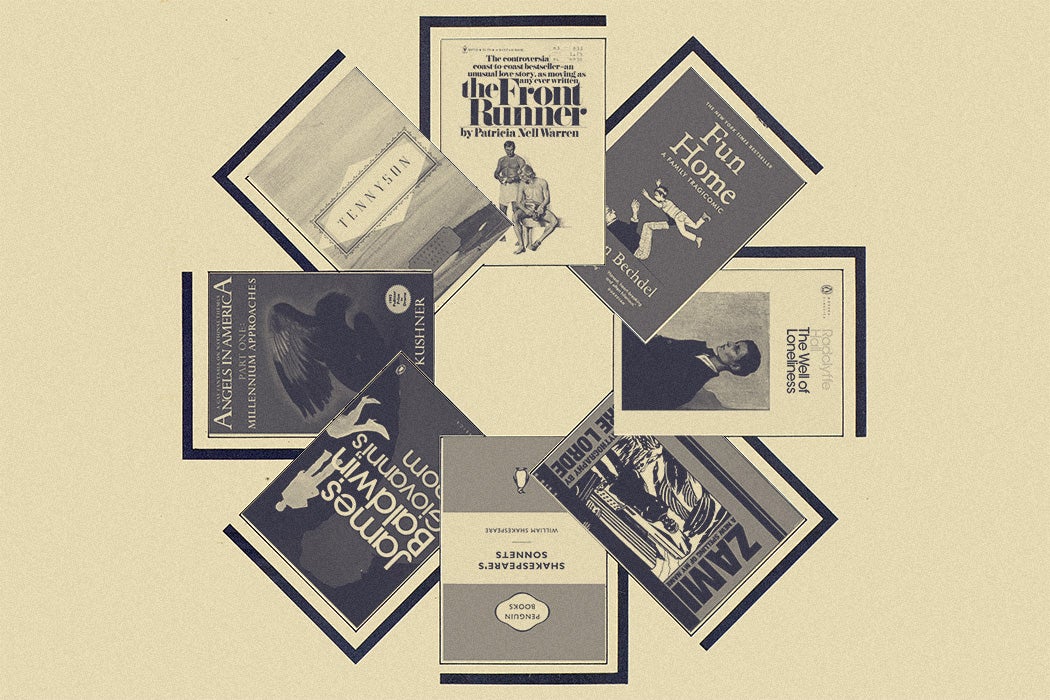

Surveying texts taught in LGBTQ+ literature courses at the time he was writing in the 2010s, Pruitt found that the five most popular titles were Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006), James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1956), Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, Part 1: Millennium Approaches (1991), and Radclyffe Hall‘s The Well of Loneliness (1928).

Weekly Newsletter

Along with literary value, purposes instructors noted in choosing specific books included capturing particular moments in history, providing fodder for interesting class discussions and self-exploration, and simply being interesting and entertaining reading for students.

Does it make sense to try to identify a canon in the field at all? Pruitt notes that such projects are often associated with a conservative orientation toward literature. But he suggests that one reason to do so is to create a shared base of knowledge for students, something that could “function as a form of collective memory.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.